Abstract

Although healthcare providers have arrived at a relatively comfortable zone of accepted clinical practice in the management of cutaneous sarcoidosis, virtually every treatment is based on minimal evidence-based data and relies almost exclusively on anecdotal information. Although it would be convenient to blame this state of affairs on the lack of certainty about disease aetiology, the unavoidable fact is that little has been executed, even in the realm of well designed comparative trials. Nonetheless, worldwide accepted standard therapies for sarcoidosis include the administration of corticosteroids, antimalarials and methotrexate.

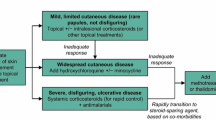

A stepwise approach to patient care is appropriate, and potent topical corticosteroids (e.g. clobetasol) or repeated intralesional injections of triamcinolone (3–10 mg/mL) may be all that is needed in mild skin-limited disease. In patients requiring systemic therapy for recalcitrant or deforming skin lesions (or for widespread disease), corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone 40–80 mg/day, tapered accordingly) used alone or in combination with antimalarials or methotrexate may be indicated. Antimalarials and methotrexate are considered second-line interventions and may be used as monotherapy for steroid-resistant sarcoidosis or in patients unable to tolerate steroids. Given the concern regarding ocular toxicity, the maximum dosages of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine should not exceed 3.5 and 6.5 mg/kg/day, respectively. Methotrexate is given in weekly doses of 10–30 mg, with the caveat that haematological, gastrointestinal, pulmonary and hepatic toxicities are possible.

Despite universal acceptance as standard care, the aforementioned treatments often result in an incomplete clinical response or unacceptable adverse events. In such situations, more innovative treatment options may be used. Treatments that may well gain widespread future use include the tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors infliximab and adalimumab. Experience is limited, but early reports are promising. Infliximab is administered via intravenous infusion at doses of 3–10 mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 weeks and as indicated thereafter, whereas adalimumab is injected subcutaneously at doses of 40 mg either weekly or every 2 weeks. Because adalimumab is not approved for the management of sarcoidosis, the optimum dose administration interval is uncertain. However, it has been given in both weekly and every other week regimens. Isotretinoin, 0.5–2 mg/kg/day, has been used successfully in a handful of reported cases. However, the teratogenic potential of isotretinoin is often prohibitive considering that the primary demographic group likely to develop sarcoidosis is women of childbearing potential. Thalidomide at dosages of 50 to >400 mg/day has limited, albeit promising, supporting data. However, access is restricted in many countries because of a deserved pregnancy category X rating. Melatonin (20 mg/day) and allopurinol (100–300 mg/day) are not well studied in cutaneous sarcoidosis, and the clinical experience with tetracycline derivatives has been mixed. That said, there are compelling reports of therapeutic benefit with both doxycycline and minocycline. Because neither of these agents is associated with the severe toxicity of cytotoxic drugs, they may serve as effective therapy in some patients. Pentoxifylline (400 mg three times daily) has been of use in a small number of reported cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis, but there are no reports on its use in patients with primarily cutaneous disease. Both ciclosporin and chlorambucil have been largely abandoned given their associated toxicity and disappointingly unreliable efficacy. Finally, laser therapy is a newer modality that may provide patients with a quick and non-invasive treatment option for cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of trade names is for product identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement.

References

Hunninghake GW, Crystal RG. Pulmonary sarcoidosi: a disorder mediated by excess helper T-lymphocyte activity at sites of disease activity. N Engl J Med 1981; 305: 429–34

English III JC, Patel PJ, Greer KE. Sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44: 725–43

Peckman DG, Spiteri MA. Sarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J 1996; 72: 196–200

Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 1224–34

Hanno B, Needleman A, Eiferman RA, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas and the development of systemic sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol 1981; 117: 203–7

Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D, editors. Fitzpatrick's color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005: 428–31

Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol 2004;31: 160–8

The Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS board of directors and by the ERS executive committee, February 1999. Statement on sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160: 736–55

Constabel U, du Bois R, Eklund A, et al. Consensus conference: activity of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 1994; 7: 624–7

Taylor AN, Cullinan P. Sarcoidosis: in search of the cause. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170: 1268–9

Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170: 1324–30

Moller DR. Treatment of sarcoidosis: from a basic science point of view. J Intern Med 2003; 253: 31–40

Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, editors. Robbins pathologic basis of disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia (PA): W. B. Saunders Company, 1999

Parham P, editor. The immune system. New York: Garland Publishing, 2000

Muller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis: immunopathogenetic concepts and their clinical application. Eur Respir J 1998; 12: 716–38

Qiu B, Frait KA, Reich F, et al. Chemokine expression dynamics in mycobacterial (type-1) and schistosomal (type-2) antigen-elicited pulmonary granuloma formation. Am J Path 2001; 158: 1503–15

Orme IM, Cooper AM. Cytokine/chemokine cascades in immunity to tuberculosis. Immunol Today 1999; 20: 307–12

Roach DR, Bean AGD, Demangel C, et al. TNF regulates chemokine induction essential for cell recruitment, granuloma formation, and clearance of mycobacterial infection. J Immunol 2002; 168: 4620–7

Crystal RG. Sarcoidosis. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Longo DL, et al., editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005: 2017–23

Miyara M, Amoura Z, Parizot C, et al. The immune paradox of sarcoidosis and regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2006; 203(2): 359–70

Badgwell C, Rosen T. Cutaneous sarcoidosis therapy updated. J Am Acad Dermatol; 56 (1): 69–83

Albertini JG, Tyler W, Miller III OF. Ulcerative sarcoidosis: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 1997; 133: 215–9

Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ 2001; 323: 334–6

Woronicz JD, Gao X, Cao Z, et al. IkB kinase-beta: NF-kB activation and complex formation with IkB kinase-alpha and NIK. Science 1997; 278: 866–9

Adcock IM. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticosteroid actions. Pulm pharmacol ther 2000; 13: 115–26

Volden G. Successful treatment of chronic skin diseases with clobetasol propionate and a hydrocolloid occlusive dressing. Act Derm Venereol 1992; 72: 69–71

Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol 1995; 131: 617–8

Russo G, Millikan LE. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: diagnosis and treatment. Compr ther 1994; 20: 418–21

Verbov J. The place of intralesional steroid therapy in dermatology. Br J Dermatol 1976; 94 Suppl. 12: 51–8

Veien NK. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: prognosis and treatment. Clin Dermatol 1986; 4: 75–87

Mycek MJ, Harvey RA, Champe PC, et al., editors. Lippincott's illustrated reviews: pharmacology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1997

Siltzbach LE. Effects of cortisone in sarcoidosis: a study of thirteen patients. Am J Med 1952; 12: 139–60

Fox RI, Kang HI. Mechanism of action of antimalarial drugs: inhibition of antigen processing and presentation. Lupus 1993; 2 Suppl. 1: S9–12

Siltzbach LE, Teirstein AS. Chloroquine therapy in 43 patients with intrathoracic and cutaneous sarcoidosis. Acta Med Scand 1964; 176 Suppl. 425: 302–6

Morse SI, Cohn ZA, Hirsch JG, et al. The treatment of sarcoidosis with chloroquine. Am J Med 1961; 30: 779–84

British Tuberculosis Association. Chloroquine in the treatment of sarcoidosis: a report from the research committee of the British Tuberculosis Association. Tubercle 1967; 48: 257–72

Baughman RP, Lower EE. Steroid-sparing alternative treatments for sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med 1997; 18: 853–64

Zic JA, Horowitz DH, Arzubiaga C, et al. Treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis with chloroquine: review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127: 1034–40

Jones E, Callen JP. Hydroxychloroquine is effective therapy for control of cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 23: 487–9

Liedtka JE. Intralesional chloroquine for the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol 1996; 35: 682–3

Burns RP. Delayed onset of chloroquine retinopathy. N Engl J Med 1966; 275: 693–6

Rigaudiere F, Ingster-Moati I, Hache JC, et al. Up-dated ophthalmological screening and follow-up management for long-term antimalarial treatment [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol 2004; 27: 191–9

Olansky AJ. Antimalarials and ophthalmologic safety. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982; 6: 19–23

Ochsendorf FR, Runne U. Chloroquine: consideration of maximum daily dose (3.5 mg/kg ideal body weight) prevents retinopathy. Dermatology 1996; 192: 382–3

Jones SK. Ocular toxicity and hydroxychloroquine: guidelines for screening. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 3–7

Grierson DJ. Hydroxychloroquine and visual screening in a rheumatology outpatient clinic. Ann Rheum Dis 1997; 56: 188–90

Mavrikakis I, Sfikakis PP, Mavrikakis E, et al. The incidence of irreversible retinal toxicity in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: a reappraisal. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 1321–6

Baughman RP, Lynch JP. Difficult treatment issues in sarcoidosis. J Intern Med 2003; 253: 41–5

Cronstein BN. The mechanism of action of methotrexate. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 1997; 23: 739–53

Lower EE, Baughman RP. The use of low dose methotrexate in refractory sarcoidosis. Am J Med Sci 1990; 299: 153–7

Webster GF, Razsi LK, Sanchez M, et al. Weekly low-dose methotrexate therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 24: 451–4

Lower EE, Baughman RP. Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 846–51

Baughman RP, Lower EE. A clinical approach to the use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Thorax 1999; 54: 742–6

Shiroky JB. The use of folates concomitantly with low-dose pulse methotrexate. Rheum Dis Clin 1997; 23: 969–79

Hassan W. Methotrexate and liver toxicity: role of surveillance liver biopsy. Conflict between guidelines for rheumatologists and dermatologists. Ann Rheum Dis 1996; 55: 273–5

Mosam A, Morar N. Recalcitrant cutaneous sarcoidosis: an evidence-based sequential approach. J Dermatol Treat 2004; 15: 353–9

Korber M, Kamp S, Kothe H, et al. Pentoxifylline inhibits secretion of O2- and TNF-alpha by alveolar macrophages in patients with sarcoidosis [in German]. Immun Infekt 1995; 23: 107–10

Marques LJ, Zheng L, Poulakis N, et al. Pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-alpha production from human alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 159: 508–11

Tong Z, Dai H, Chen B, et al. Inhibition of cytokine release from alveolar macrophages in pulmonary sarcoidosis by pentoxifylline: comparison with dexamethasone. Chest 2003; 124: 1526–32

Baughman RP, Iannuzzi M. Tumor necrosis factor in sarcoidosis and its potential for targeted therapy. BioDrugs 2003; 17: 425–31

Moller DR, Wysocka M, Greenlee BM, et al. Inhibition of human interleukin-12 production by pentoxifylline. Immunol 1997; 91: 197–203

Zabel P, Entzian P, Dalhoff K, et al. Pentoxifylline in treatment of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155: 1665–9

Inoue K, Hirohisa T, Yanagisawa R, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of pentoxifylline. Chest 2004; 126: 321

Marshall TG, Marshall FE. Sarcoidosis succumbs to antibiotics: implications for autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev 2004; 3: 295–300

Marshall TG, Marshall FE. Antibiotics in sarcoidosis: reflections of the first year. J Indep Med Res 2003; 1: 2 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.joimr.org/phorum/read.php?f=2&i=38&t=38 [Accessed 2005 Jun 28]

Webster GF, Toso SM, Hegemann L. Inhibition of a model of in vitro granuloma formation by tetracyclines and ciprofloxacin: involvement of protein kinase C. Arch Dermatol 1994; 130: 748–52

Bikowski JB. Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline for acne and rosacea. Skinmed 2003; 2: 234–45

Kelly KJ, Sutton TA, Weathered N, et al. Minocycline inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in a rat model of ischemic renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2004; 287: F760–6

Thong YH, Ferrante A. Inhibition of mitogen-induced human lymphocyte proliferative responses by tetracycline analogues. Clin Exp Immunol 1979; 35: 443–6

Thong YH, Ferrante A. Effect of tetracycline treatment on immunologic responses in mice. Clin Exp Immunol 1980; 39: 728–32

Bachelez H, Senet P, Cadranel J, et al. The use of tetracyclines for the treatment of sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 69–73

Veien NK, Stahl D, Brodthagen H. Granulomatous rosacea treated with tetracycline. Dermatologica 1981; 163: 267–9

Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol 1985; 65: 270–2

Nguyen EH, Wolverton SE. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, editor. Comprehensive dermatologie drug therapy. Philadelphia (PA): W. B. Saunders, 2001: 269–310

Massacesi L, Castigli E, Vergelli M, et al. Immunosuppressive activity of 13-cis-retinoic acid and prevention of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in rats. J Clin Invest 1991; 88: 1331–7

Dupuy P, Bagot M, Heslan M, et al. Synthetic retinoids inhibit the antigen presenting properties of epidermal cells in vitro. J Invest Dermatol 1989; 93: 455–9

Waldinger TP, Ellis CN, Quint K, et al. Treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis with isotretinoin. Arch Dermatol 1983; 119: 1003–5

Vaillant L, le Marchand D, Bertrand S, et al. Annular cutaneous sarcoidosis of the forehead: treatment with isotretinoin [in French]. Ann Derm Venereol 1986; 113: 1089–92

Georgiou S, Monastirli A, Pasmatzi E, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: complete remission after oral isotretinoin therapy. Acta Derm Venereol 1998; 78: 457–9

Chong WS, Tan HH, Tan SH. Cutaneous sarcoidosis in Asians: a report of 25 patients from Singapore. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005; 30: 120–4

Goodfield M, Cox N, Dudley A, et al. Clinical guidelines: advice on the safe introduction and continued use of isotretinoin in can [online]. Available from URL: http://www.bad.org.uk/healthcare/guidelines/acne.asp [Accessed 2005 Jun 29]

iPLEDGE™ program [online]. Available at URL: https://www.ipledgeprogram.com [Accessed 2007 Aug 18]

Breedveld FC, Dayer JM. Leflunomide: mode of action in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2000; 59: 841–9

Majithia V, Sanders S, Harisdangkul V, et al. Successful treatment of sarcoidosis with leflunomide. Rheumatology 2003; 42: 700–2

Baughman RP, Lower EE. Leflunomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoid Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2004; 21: 43–8

Chong ASF, Huang W, Liu W, et al. In vivo activity of leflunomide: pharmacokinetic analyses and mechanism of immunosuppression. Transplantation 1999; 68: 100–9

Fischer TW, Bauer HI, Graefe T, et al. Erythema multiformelike drug eruption with oral involvement after intake of leflunomide. Dermatol 2003; 207: 386–9

Bandyopadhyay D. Exfoliative dermatitis induced by leflunomide therapy. J Dermatol 2003; 30: 845–6

McHugh SM, Rifkin IR, Deighton J, et al. The immunosuppressive drug thalidomide induces T helper cell type 2 (Th2) and concomitantly inhibits Th1 cytokine production in mitogen-and antigen-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Clin Exp Immunol 1995; 99: 160–7

Meierhofer C, Dunzendorfer S, Wiedermann CJ. Theoretical basis for the activity of thalidomide. BioDrugs 2001; 15: 681–703

Perri III AJ, Hsu S. A review of thalidomide's history and current dermatologic applications. Dermatol Online J 2003 Aug; 9(3): 5

U.S. Food and Drug Administration [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov [Accessed 2008 Mar 5]

Sampaio EP, Sarno EN, Galilly R, et al. Thalidomide selectively inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha production by stimulated human monocytes. J Exp Med 1991; 173: 699–703

Tavares JL, Wangoo A, Dilworth P, et al. Thalidomide reduces tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by human alveolar macrophages. Respir Med 1997; 91: 31–9

Moreira AL, Sampaio EP, Zmuidzinas A, et al. Thalidomide exerts its inhibitory action on tumor necrosis factor alpha by enhancing mRNA degradation. J Exp Med 1993; 177: 1675–80

Corral LG, Haslett PAJ, Muller GW, et al. Differential cytokine modulation and T-cell activation by two distinct classes of thalidomide analogues that are potent inhibitors of TNF-alpha. J Immunol 1999; 163: 308–6

Oliver SJ, Kikuchi T, Krueger JG, et al. Thalidomide induces granuloma differentiation in sarcoid skin lesions associated with disease improvement. Clin Immunol 2002; 102: 225–36

Moller DR, Wysocka M, Greenlee BM, et al. Inhibition of IL-12 production by thalidomide. J Immunol 1997; 159: 5157–61

Barriere H. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: treatment with thalidomide [in French]. Presse Med 1983; 12: 963

Carlesimo M, Giustini S, Rossi A, et al. Treatment of cutaneous and pulmonary sarcoidosis with thalidomide. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32: 866–9

Rousseau L, Beylot-Barry M, Doutre MS, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis successfully treated with low dose of thalidomide. Arch Dermatol 1998; 134: 1045–6

Grasland A, Pouchot J, Chaumaiziere D, et al. Effectiveness of thalidomide treatment during cutaneous sarcoidosis [in French]. Rev Med Interne 1998; 19: 208–9

Lee JB, Koblenzer PS. Disfiguring cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis treated with thalidomide: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 39: 835–8

Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein AS, et al. Thalidomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Chest 2002; 122: 227–32

Nguyen YT, Dupuy A, Cordoliani F, et al. Treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis with thalidomide. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 50: 235–41

Bastuji-Garin S, Ochonisky S, Bouche P, et al. Incidence and risk factors for thalidomide neuropathy: a prospective study of 135 dermatologic patients. J Invest Dermatol 2002; 119: 1020–6

Scallon B, Cai A, Solowski N, et al. Binding and functional comparisons of two types of tumor necrosis factor antagonists. J Pharm Exp Ther 2002; 301: 418–26

Meyerle JH, Shorr A. The use of infliximab in cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Drugs Dermatol 2003; 2: 413–4

Mallbris L, Ljungberg A, Hedblad MA, et al. Progressive cutaneous sarcoidosis responding to anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 48: 290–3

Roberts SD, Wilkes DS, Burgett RA, et al. Refractory sarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Chest 2003; 124: 2028–31

Haley H, Cantrell W, Smith K. Infliximab therapy for sarcoidosis (lupus pernio). Br J Dermatol 2004; 150: 146–9

Heffernan MP, Anadkat MJ. Recalcitrant cutaneous sarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Arch Dermatol 2005 Jul; 141: 910–1

Rosen T, Doherty C. Successful long-term management of refractory cutaneous and upper airway sarcoidosis with periodic infliximab infusions. Dermatol Online J 2007; 13(3): 14

Kobylecki C, Shaunuk S. Refractory neurosarcoidosis responsive to infliximab. Pract Neurol 2007 Apr; 7(2): 112–5

Yee AMF, Pochapin MB. Treatment of complicated sarcoidosis with infliximab anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135: 27–31

Ulbricht KU, Stoll M, Bierwirth J, et al. Successful tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade treatment in therapy-resistant sarcoidosis. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48: 3542–3

Pritchard C, Nadarajah K. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor treatment for sarcoidosis refractory to conventional treatments: a report of five patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 318–20

Uthman I, Tourna Z, Khoury M. Cardiac sarcoidosis responding to monotherapy with infliximab. Clin Rhematol 2007 Nov; 26(11): 2001–3

Baughman RP, Lower EE. Infliximab for refractory sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2001; 18: 70–4

Doty JD, Mazur JE, Judson MA. Treatment of sarcoidosis with infliximab. Chest 2005; 127: 1064–71

Sweiss NJ, Welsch MJ, Curran JJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor inhibition as a novel treatment for refractory sarcoidosis. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 53: 788–91

Saleh S, Ghodsian S, Yakimova V, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab in treated selected patients with sarcoidosis. Respir Med 2006; 100: 2053–9

Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, et al. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006 Jul; 174: 795–802

Keane J, Sharon G, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor-necrosis factor (alpha)-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1098–104

Helbling D, Breitbach TH, Krause M. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection in Crohn's disease following anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 14: 1393–5

Brown SL, Greene MH, Gershon SK, et al. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy and lymphoma development: twentysix cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46: 3151–8

Wood KL, Hage CA, Knox KS, et al. Histoplasmosis after treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 1279–82

Lebwohl M, Bagel J, Gelfand JM, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: monitoring and vaccinations in patients treated with biologies for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 58(1): 94–105

Sturfel G, Christensson B, Bynke G, et al. Neurosarcoidosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis during treatment with infliximab. J Rhematol 2007; 34: 2313

Almodovar R, Izquierdo M, Zarco P, et al. Pulmonary sarcoidosis in a patient treated with ankylosing spondylitis treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007; 25: 99–101

Sweiss NJ, Baughman RP. Tumor necrosis factor inhibition in the treatment of refractory sarcoidosis: slaying the dragon? J Rheumatol 2007; 34: 2129–31

Jackson CG, Williams HJ. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: using their clinical pharmacological effects as a guide to their selection. Drugs 1998; 56: 337–44

Kataria YP. Chlorambucil in sarcoidosis. Chest 1980; 78: 36–43

Hughes Jr GS, Kataria YP, O'Brien TF. Sarcoidosis presenting as biliary cirrhosis: treatment with chlorambucil. South Med J 1983; 76: 1440–2

Isreal HL, McComb BL. Chlorambucil treatment of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis 1991; 8: 35–41

Sahgal SM, Sharma OP. Fatal herpes simplex infection during chlorambucil therapy for sarcoidosis. J R Soc Med 1984; 77: 144–6

Chen Q, Wei W. Effects and mechanisms of melatonin on inflammatory and immune responses of adjuvant arthritis rat. Int Immunopharmacol 2002; 2: 1443–9

Di Stefano A, Paulesu L. Inhibitory effect of melatonin on production of IFN-gamma or TNF-alpha in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of some blood donors. J Pineal Res 1994; 17: 164–9

Liu F, Ng TB, Fung MC. Pineal indoles stimulate the gene expression of immunomodulating cytokines. J Neural Transm 2001; 108: 397–405

Garcia-Maurino S, Gonzalez-Haba MG, Calvo JR, et al. Melatonin enhances IL-2, IL-6, and IFN-gamma production by human circulating CD4+ cells: a possible nuclear receptor-mediated mechanism involving T helper type 1 lymphocytes and monocytes. J Immunol 1997; 159: 574–81

Arzt ES, Fernandez-Castelo S, Finocchiaro LME, et al. Immunomodulation by indoleamines: serotonin and melatonin action on DNA and interferon-gamma synthesis by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Immunol 1988; 8: 513–20

Cagnoni ML, Lombardi A, Cerinic MM, et al. Melatonin for treatment of chronic refractory sarcoidosis. Lancet 1995; 346: 1229–30

Pignone AM, Del Russo A, Fiori G, et al. Melatonin is a safe and effective treatment for chronic pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. J Pineal Res 2006; 41: 95–100

Mulchahey JJ, Goldwater DR, Zemlan FP. A single blind, placebo controlled, across groups dose escalation study of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the melatonin analog beta-methyl-6-chloromelatonin. Life Sci 2004; 75: 1843–56

Ho S, Clipstone N, Timmerman L, et al. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1996; 80: S40–5

Martinet Y, Pinkston P, Saltini C, et al. Evaluation of the in vitro and in vivo effects of cyclosporine on the T-lymphocyte alveolitis of active pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am Rev Repir Dis 1988; 138: 1242–8

Losa Garcia JE, Mateos Rodriguez F, Jimenez Lopez A, et al. Effect of cyclosporin A on inflammatory cytokine production by human alveolar macrophages. Respir Med 1998; 92: 722–8

Rebuck AS, Stiller CR, Braude AC, et al. Cyclosporin for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Lancet 1984; I(8387): 1174

O'Callaghan CA, Wells AU, Lalvani A, et al. Effective use of cyclosporin in sarcoidosis: a treatment strategy based on computed tomography scanning. Eur Respir J 1994; 7: 2255–6

Rebuck AS, Sanders BR, MacFadden DK, et al. Cyclosporin in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Lancet 1987; I(8548): 1486

Losada A, Garcia-Doval I, de la Torre C, et al. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis worsened by cyclosporin treatment for pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol 1998; 138: 1091–104

Hammond JMJ, Bateman ED. Successful treatment of life threatening steroid-resistant pulmonary sarcoidosis with cyclosporin in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Repir Med 1990; 84: 77–80

Wyser CP, van Schalkwyk EM, Alheit B, et al. Treatment of progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis with cyclosporin A. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156: 1371–6

Kahan BD. Cyclosporine. N Engl J Med 1989; 321: 1725–38

Mizuno K, Okamoto H, Horio T. Inhibitory influences of xanthine oxidase inhibitor and angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitor on multinucleated giant cell formation from monocytes by downregulation of adhesion molecules and purinergic receptors. Br J Dermatol 2004; 150: 205–10

Mizuno K, Okamoto H, Horio T. Heightened ability of monocytes from sarcoidosis to form multi-nucleated giant cells in vitro by supernatants of concanavalin A-stimulated mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2001; 126: 151–6

Chensue SW, Warmington K, Ruth J, et al. Cytokine responses during mycobacterial and schistosomal antigen-induced pulmonary granuloma formation: production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines and relative contribution of tumor necrosis factor. Am J Path 1994; 145: 1105–13

Rosef BM. Allopurinol for sarcoid? N Engl J Med 1976; 294: 447

Pollock JL. Sarcoidosis responding to allopurinol. Arch Dermatol 1980; 116: 273–4

Brechtel B, Haas N, Henz BM, et al. Allopurinol: a therapeutic alternative for disseminated cutaneous sarcoidosis. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135: 307–9

Antony F, Layton AM. A case of cutaneous acral sarcoidosis with response to allopurinol. Br J Dermatol 2000; 142: 1052–3

Pfau A, Stolz W, Karrer S, et al. Allopurinol in treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis [in German]. Hautarzt 1998; 49: 216–8

El-Euch D, Mokni M, Trojjet S, et al. Sarcoidosis in a child treated successfully with allopurinol. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 1184–5

Samuel M, Allen GE, McMillian SC, et al. Sarcoidosis: initial results on six patients treated with allopurinol. Br J Dermatol 1984; 111(S26): 20

Voelter-Mahlknecht S, Benez A, Metzger S, et al. Treatment of subcutaneous sarcoidosis with allopurinol. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135: 1560–1

O'Donoghue NB, Barlow RJ. Laser remodeling of nodular nasal lupus pernio. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31: 27–9

James JC, Simpson CB. Treatment of laryngeal sarcoidosis with CO2 laser and mitomycin-C. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130: 262–4

Grema H, Greve B, Raulin C. Scar sarcoidosis: treatment with the Q-switched ruby laser. Lasers Surg Med 2002; 30: 398–400

Goodman MM, Alpern K. Treatment of lupus pernio with the flashlamp pulsed dye laser. Lasers Surg Med 1992; 12: 549–51

Cliff S, Felix RH, Singh L, et al. The successful treatment of lupus pernio with the flashlamp pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther 1999; 1: 49–52

Stack Jr BC, Hall PJ, Goodman AL, et al. CO2 laser excision of lupus pernio of the face. Am J Otolaryngol 1996; 17: 260–3

Young HS, Chalmers RJ, Griffiths CE, et al. CO2 laser vaporization for disfiguring lupus pernio. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2002; 4: 87–90

Green JJ, Lawrence N, Heymann WR. Generalized ulcerative sarcoidosis induced by therapy with the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 507–8

Kormeili T, Neel V, Moy RL. Cutaneous sarcoidosis at sites of previous laser surgery. Cutis 2004; 73: 53–5

Humira® [online]. Available from URL: http://www.humira.com [Accessed 2008 Mar 7]

Philpis MA, Lynch J, Azmi FH. Ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis responding to adalimumab. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53(5): 917

Heffernan MP, Smith DI. Adalimumab for treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol 2006; 142: 17–9

Callejas-Rubio JL, Ortego-Centeno N, Lopez-Perez L, et al. Treatment of therapy-resistant sarcoidosis with adalimumab. Clin Rhematol 2006; 25: 596–7

U.S. National Institutes of Health clinical trials. A study of adalimumab to treat sarcoidosis of the skin (NCT 00274352) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00274352?term=NCT+00274352&rank=1 [Accessed 2008 Mar 7]

Levalampi T, Korpela M, Vuolteenaho K, et al. Etandercept and adalimumab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathies in clinical practice: adverse events and other reasons leading to discontinuation. Rheumatol Int 2008; 28: 261–9

Berglund F, Flodh H, Lundborg P, et al. Drug use during pregnancy and breast-feeding: a classification system for drug information. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 1984; 126: 1–55

Brent R. Experts' answers. Health Physics Society [online]. Available from URL: http://www.hps.org [Accessed 2006 Jan19]

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doherty, C.B., Rosen, T. Evidence-Based Therapy for Cutaneous Sarcoidosis. Drugs 68, 1361–1383 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200868100-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200868100-00003