Abstract

For the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI), international guidelines recommend primary percutaneous coronary intervention with adjunctive antithrombotic therapy, the management of complications, and secondary prevention measures. Delivery of care has, however, lagged behind establishing the evidence for effectiveness. Approximately a quarter of all patients with STEMI still fail to receive reperfusion therapy. Additionally, for most patients delays substantially exceed guideline recommendations and secondary prevention is incomplete. What can be done? First, cardiologists need to take the lead in improving systems of care, with the integration of prehospital care within 'heart attack networks' involving intervention centers, nonintervention hospitals, primary care, and paramedic ambulance care. Several examples show that such systems are feasible. 'Door-to-balloon' initiatives can improve care in the final interventional hospital, but only make a modest contribution to total patient delay. Second, high-risk patients, including the elderly and those with cardiac complications like heart failure, should be targeted for more-aggressive interventional and pharmacologic therapy; the opposite situation currently exists in clinical practice (the treatment–risk paradox). Third, greater emphasis on quality improvement, collaboration among health professionals, and achieving high-quality care for all is required from funding bodies, regulatory agencies and professional societies.

Key Points

-

Data from registries and European surveys demonstrate that there is a substantial gap between evidence-based recommendations for the management of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and clinical practice

-

Although a considerable proportion of patients now receive primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), about a quarter of all patients with STEMI fail to receive reperfusion therapy

-

Only a minority of patients currently achieve reperfusion within the first 2–3 h of symptom onset

-

Substantial heterogeneity exists across Europe in the provision of reperfusion therapy, time delays, and the extent to which integrated 'heart attack networks' have been developed

-

The goal of providing rapid and comprehensive reperfusion to all patients is achievable, and has been shown to be feasible, but requires a focus on improving systems of acute care and integrating prehospital emergency systems, primary care and PCI centers, and non-PCI hospitals ('heart attack networks')

-

The diversity of health-care systems, and the differences in geography and population distribution across Europe, mean that the principles of providing an integrated and expedited system of care for acute STEMI will need to be adapted regionally; nevertheless, the same principles apply to all health-care systems and few currently meet the guideline recommendations

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fox KAA et al. for the GRACE Investigators (2007) Decline in rates of death and heart failure in acute coronary syndromes, 1999–2006. JAMA 297: 1892–1900

Antman EM et al. on behalf of the Writing Group (2008) 2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 210–247

Silber S et al. for the Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology (2005) Guidelines for percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J 26: 804–847

Mandelzweig L et al. for the Euro Heart Survey Investigators (2006) The second Euro Heart Survey on acute coronary syndromes: characteristics, treatment, and outcome of patients with ACS in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin in 2004. Eur Heart J 27: 2285–2293

Blomkalns AL et al. (2007) Guideline implementation research: exploring the gap between evidence and practice in the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. Acad Emerg Med 14: 949–954

Eagle KA et al. for the GRACE Investigators (2008) Trends in acute reperfusion therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction from 1999 to 2006: we are getting better but we have got a long way to go. Eur Heart J 29: 609–617

Bassand JP et al. (2005) Implementation of reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction: a policy statement from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 26: 2733–2741

Nallamothu BK et al. (2006) Driving times and distances to hospitals with percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: implications for prehospital triage of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 113: 1189–1195

Nallamothu BK et al. (2007) Development of systems of care for ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients: gaps, barriers, and implications. Circulation 116: e68–e72

ACC D2B Alliance [http://www.d2balliance.com/]

Nallamothu BK et al. (2007) Comparing hospital performance in door-to-balloon time between the Hospital Quality Alliance and the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 1517–1519

AHA (online 31 May 2007) Mission: Lifeline—a new plan to decrease deaths from major heart blockages. [http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3048034] (accessed 17 June 2008)

Boersma E for the Primary Coronary Angioplasty vs Thrombolysis (PCAT)-2 Trialists' Collaborative Group (2006) Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J 27: 779–788

Nallamothu BK et al. for the NRMI Investigators (2005) Times to treatment in transfer patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI)-3/4 analysis. Circulation 111: 761–767

Kalla K et al. for the Vienna STEMI Registry Group (2006) Implementation of guidelines improves the standard of care: the Viennese registry on reperfusion strategies in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (Vienna STEMI registry). Circulation 113: 2398–2405

Nallamothu B et al. for the GRACE Investigators (2007) Relationship of treatment delays and mortality in patients undergoing fibrinolysis and primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart 93: 1552–1555

Chevalier V et al. (2003) Impact of a public-directed media campaign on emergency call to mobile intensive care units center for acute chest pain [French]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 52: 150–158

Huber K et al. for the Task Force on Pre-hospital Reperfusion Therapy of the Working Group on Thrombosis of the ESC (2005) Prehospital reperfusion therapy: a strategy to improve therapeutic outcome in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 26: 2063–2074

Eagle KA et al. for the GRACE Investigators (2002) Practice variation and missed opportunities for reperfusion in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Lancet 359: 373–377

Steinbuch R (2007) Regulatory changes for the treatment of patients with heart attacks. Am J Cardiol 99: 1166–1167

Birkhead JS et al. (2006) Impact of specialty of admitting physician and type of hospital on care and outcome for myocardial infarction in England and Wales during 2004–5: observational study. BMJ 332: 1306–1311

Kalla K et al. (2008) One year mortality of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Primary PCI versus thrombolytic therapy in the VIENNA-STEMI Registry [abstract #1024-46]. J Am Coll Cardiol 51 (Suppl A): A213

Montalescot G et al. for the RIVIERA Investigators (2007) Predictors of outcome in patients undergoing PCI: results of the RIVIERA study. Int J Cardiol [10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.127]

Ting HH et al. (2007) Regional systems of care to optimize timeliness of reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the Mayo Clinic STEMI Protocol. Circulation 116: 729–736

Rokos IC et al. (2006) Rationale for establishing regional ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks. Am Heart J 152: 661–667

Boersma E for the Primary Coronary Angioplasty vs Thrombolysis Group (2006) Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J 27: 779–788

Stenestrand U et al. for the RIKS-HIA Registry (2006) Long-term outcome of primary percutaneous coronary intervention vs prehospital and in-hospital thrombolysis for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 296: 1749–1756

Zijlstra F et al. (1997) Randomized comparison of primary coronary angioplasty with thrombolytic therapy in low risk patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 29: 908–912

Bonnefoy E et al. for the Comparison of Angioplasty and Prehospital Thrombolysis in Acute Myocardial Infarction study group (2002) Primary angioplasty versus prehospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction: a randomised study. Lancet 360: 825–829

Widimsky P et al. for the PRAGUE Study Group Investigators (2003) Long distance transport for primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction: final results of the randomized national multicentre trial—PRAGUE-2. Eur Heart J 24: 94–104

Morrison LJ et al. (2000) Mortality and prehospital thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. JAMA 283: 2686–2692

Danchin N et al. for the USIC 2000 Investigators (2004) Impact of prehospital thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction on 1-year outcome: results from the French Nationwide USIC 2000 Registry. Circulation 110: 1909–1915

Faxon DP (2007) Development of systems of care for ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients: current state of ST-elevation myocardial infarction care. Circulation 116: e29–e32

Jacobs AK et al. for the American Heart Association's Acute Myocardial Infarction Advisory Working Group (2006) Recommendation to develop strategies to increase the number of ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients with timely access to primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 113: 2152–2163

Jollis JG et al. (2006) Reperfusion and acute myocardial infarction in North Carolina emergency departments (RACE): study design. Am Heart J 152: 851.e1–851.e11

Le May MR et al. (2008) A citywide protocol for primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 358: 231–240

The Lothian Optimal Reperfusion Programme. Report to the Scottish Government 2008 [http://www.archive.nhsscotland.com]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fox, K., Huber, K. A European perspective on improving acute systems of care in STEMI: we know what to do, but how can we do it?. Nat Rev Cardiol 5, 708–714 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1343

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1343

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the treatment delay in the care of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing acute percutaneous coronary intervention: a cross-sectional study

BMC Health Services Research (2015)

-

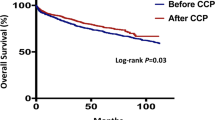

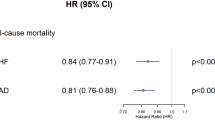

One-year mortality in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the Vienna STEMI registry

Wiener klinische Wochenschrift (2015)