Abstract

Purpose

‘Cyberchondria’ describes a pattern of researching health information online motivated by distress or anxiety about health, which becomes excessive and in turn increases distress. The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS) assesses this construct. The aims of the present study were to validate a German version of the CSS and to propose a short form.

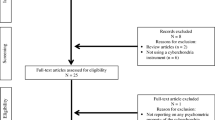

Method

The CSS was translated and posted online. Inclusion criteria were fulfilled by n = 500 participants (age 29.1 ± 10.4 years, 73.6 % women). Item analyses, an exploratory factor analysis and correlations with health anxiety, somatic symptoms, health-care utilization and depression were calculated. A brief version with 15 items was developed (CSS-15) and validated in a second sample (n = 292; age 24.2 ± 4.1 years, 76.4 % women).

Results

The internal consistency of the CSS was α = .93 and its split-half reliability α = .95. The mean item-total correlation was r itc = .51, the mean inter-item correlation r = .29 and the mean item difficulty p i = .36. The principal component analysis extracted five factors. The CSS score correlated highly with health anxiety and moderately with somatic symptoms and health-care utilization. The CSS-15 still had an internal consistency of α = .82 and the confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the five factors. The correlation coefficients with health-related measures were unaffected.

Conclusion

The German version of the CSS possesses very good psychometric characteristics, which were preserved in a short version. The factorial structure was replicated. The correlations with health anxiety and depression for both scales underscore their validity and clinical relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nicholas D, Huntington P, Gunter B, Withey R, Russell C, editors. The British and their use of the web for health information and advice: a survey. Aslib Proceedings 2003; MCB UP Ltd.

Loos A. Cyberchondria: too much information for the health anxious patient? J Consum Health Internet. 2013;17(4):439–45.

Tang H, Ng JHK. Googling for a diagnosis—use of google as a diagnostic aid: internet based study. BMJ. 2006;333(7579):1143–5.

Cline RJ, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: the state of the art. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(6):671–92.

Lemire M, Sicotte C, Paré G. Internet use and the logics of personal empowerment in health. Health Policy. 2008;88(1):130–40.

Leykin Y, Muñoz RF, Contreras O. Are consumers of internet health information “cyberchondriacs”? characteristics of 24,965 users of a depression screening site. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(1):71–7.

McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient–health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1):24–8.

McManus F, Leung C, Muse K, Williams JMG. Understanding ‘cyberchondria’: an interpretive phenomenological analysis of the purpose, methods and impact of seeking health information online for those with health anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther. 2014;7:e21.

Norr AM, Capron DW, Schmidt NB. Medical information seeking: impact on risk for anxiety psychopathology. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2014;45(3):402–7.

Salkovskis PM, Warwick HM. Morbid preoccupations, health anxiety and reassurance: a cognitive-behavioural approach to hypochondriasis. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24(5):597–602.

Baumgartner SE, Hartmann T. The role of health anxiety in online health information search. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(10):613–8.

White RW, Horvitz E. Cyberchondria: studies of the escalation of medical concerns in web search. ACM Trans Inf Syst. 2009;27(4):23.

Starcevic V, Berle D. Cyberchondria: towards a better understanding of excessive health-related Internet use. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(2):205–13.

McElroy E, Shevlin M. The development and initial validation of the cyberchondria severity scale (CSS). J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(2):259–65.

Fergus TA. The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS): an examination of structure and relations with health anxiety in a community sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(6):504–10.

Norr AM, Allan NP, Boffa JW, Raines AM, Schmidt NB. Validation of the cyberchondria severity scale (CSS): replication and extension with bifactor modeling. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;31:58–64.

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, Diguiseppi C, Wentz R, Kwan I, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:MR000008.

Andreassen HK, Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Chronaki CE, Dumitru RC, Pudule I, Santana S, et al. European citizens’ use of E-health services: a study of seven countries. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):53.

Eastin MS, Guinsler NM. Worried and wired: effects of health anxiety on information-seeking and health care utilization behaviors. CyberPsychol Behav. 2006;9(4):494–8.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–91.

Bailer J, Rist F, Müller T, Mier D, Diener C, Ofer J, et al. German validation of the short health anxiety inventory (SHAI). Verhaltentherapie Verhaltensmedizin. 2013;34:378–98.

Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick H, Clark D. The health anxiety inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32(05):843–53.

Alberts NM, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Jones SL, Sharpe D. The short health anxiety inventory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(1):68–78.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–66.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–59.

Mewes R, Rief W, Brähler E, Martin A, Glaesmer H. Lower decision threshold for doctor visits as a predictor of health care use in somatoform disorders and in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):349–55.

Hautzinger M, Bailer M. Die allgemeine depressionsskala (ADS). Weinheim: Beltz Test Verlag; 1993.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30(2):179–85.

Zwick WR, Velicer WF. Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychol Bull. 1986;99(3):432.

Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. J Educ Res. 2006;99(6):323–38.

Starcevic V, Aboujaoude E. Cyberchondria, cyberbullying, cybersuicide, cybersex: “new” psychopathologies for the 21st century? World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):97–100.

Takahashi Y, Ohura T, Ishizaki T, Okamoto S, Miki K, Naito M, et al. Internet use for health-related information via personal computers and cell phones in Japan: a cross-sectional population-based survey. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e110.

Baker L, Wagner TH, Singer S, Bundorf MK. Use of the Internet and e-mail for health care information: results from a national survey. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2400–6.

Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ. Chronic illness and health-seeking information on the Internet. Health. 2007;11(3):327–47.

Rice RE. Influences, usage, and outcomes of Internet health information searching: multivariate results from the Pew surveys. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75(1):8–28.

Bailer J, Witthöft M. Modifizierte kurzform des health anxiety inventory (MK-HAI). In: Glöckner-Rist A, editor. ZUMA-informationssystem elektronisches handbuch sozialwissenschaftlicher erhebungsinstrumente version 100. Mannheim: Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen; 2006.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript would like to thank Franziska Jeromin for her help with the translation of the CSS and Louisa Lühn for her support with data acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding body agreements and policies

All authors are employed by the Philipps-University Marburg.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript do not have any actual or potential conflict of interest to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barke, A., Bleichhardt, G., Rief, W. et al. The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS): German Validation and Development of a Short Form. Int.J. Behav. Med. 23, 595–605 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9549-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9549-8