Abstract

Cyberchondria refers to the excessive and repeated searching for medical information on the Internet and may be considered as health-related problematic Internet use. Previous findings indicated that cyberchondria is positively associated with health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Also, research suggests that excessive or problematic Internet use as well as health worries and compulsive behaviors are present among individuals with low self-esteem. This study sought to examine: (1) the association between self-esteem and cyberchondria, and (2) the mediating role of health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. Participants (N = 207) from a community sample completed self-report measures assessing global self-esteem, health anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and cyberchondria. We found that self-esteem directly predicted cyberchondria and that health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms parallelly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. These findings suggest that low self-esteem, health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms can be considered vulnerability factors for cyberchondria. In addition, the reverse mediation model indicated that cyberchondria potentially predicts self-esteem both directly and through health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. The bidirectional relationship among the analyzed variables are discussed in the context of potential psychological predictors and consequences of cyberchondria and possible mechanisms explaining cyberchondria. The current study provides further insight into the conceptualization of cyberchondria and the feasibility of specific treatment directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Excessive searching for health-related information on the Internet accompanied by health worry has become increasingly prevalent among adult Internet users. This phenomenon, referred to as “cyberchondria”, is characterized by frequent and repetitive seeking for medical information online, and associated with the exacerbation of anxious thoughts and feelings about health (Starcevic and Berle 2013, 2015). If anxiety intensifies, it may result in ceasing the search or, quite the opposite it may stimulate further online investigation. This behavioral pattern, which appears to resemble compulsive behaviors, is a form of reassurance seeking that is intended to reduce fear of illness and to restore confidence about good health. Paradoxically, however, it may become a source of even greater anxiety (Starcevic and Berle 2013). Cognitive-affective components like worrying about health and behavioral factors, such as excessive and repeated online searching for medical information, can be regarded as the most salient characteristics of cyberchondria (Starcevic 2017). Apparently, cyberchondria may have negative consequences, such as the exacerbation of a fear of illnesses, confusion about conflicting medical information, preoccupation with online searching for health-related content at the expense of personal, social and other activities, and potentially a disruption of the relationship with primary care physicians (Starcevic and Berle 2013; McElroy and Shevlin 2014).

Recent research has linked cyberchondria to excessive or problematic Internet use (PIU; Fergus and Dolan 2014; Fergus and Spada 2017) and even Internet addiction (Ivanova 2013; Selvi et al. 2018; Durak-Batigun et al. 2018). PIU as a form of maladaptive behavior may lead to significant distress and impairment of daily functioning (Young 1998; Davis 2001; Shapira et al. 2003; Weinstein and Aboujaoude 2015; Laconi et al. 2017). Linking cyberchondria to PIU is based upon the reasoning that health anxiety leads to excessive Internet searching for health-related content (Baumgartner and Hartmann 2011; Muse et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2016) to obtain reassurance about good health. As specified by Meerkerk et al. (2009), components of PIU, such as uncontrollability of Internet use, mental and behavioral preoccupation, and modification of mood, seem to be relevant for cyberchondriac behaviors. In addition, one of the purposes of PIU behaviors is to release tension and mitigate distress. Similarly, cyberchondria’s excessive searching can be perceived as helpful behaviors in gaining reassurance and reduce stress related to health issues. The outcome, however, for both cyberchondria (Starcevic and Berle 2013; Starcevic 2017) and PIU (Davis 2001; Shapira et al. 2003) is opposite i.e., an increase in anxious feelings and distress.

Health Anxiety, Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms and Cyberchondria

The most recent meta-analysis has summarized data on positive association of health anxiety with cyberchondria (McMullan et al. 2019). According to the cognitive–behavioral model of health anxiety (Warwick and Salkovskis 1990; Cooper et al. 2017; Salkovskis and Warwick 2001), the general dysfunctional beliefs about health, erroneous appraisals of nonthreatening symptoms as a serious health threat, and intolerance of any uncertainty related to health may evoke health anxiety as well as attempts to reduce it through safety seeking i.e., searching for reassurance of good health (Abramowitz and Braddock 2006). Within the framework of the cognitive–behavioral model health anxiety may lead to cyberchondria as a form of safety seeking behaviors (Fergus 2014; Fergus and Dolan 2014). Thus, individuals with heightened distress and worry about health may also intensively and repeatedly seek for health-related information on the Internet (Hadjistavropoulos et al. 1998) to gain reassurance and psychological comfort (Baumgartner and Hartmann 2011; Muse et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2016). However, the reassurance so afforded is probably temporary thus prompting an individual to further seek medical information, which in effect may reinforce the fear of illness (Kobori and Salkovskis 2012; Salkovskis and Warwick 2001). This suggests that health-related excessive online activity i.e., cyberchondria might play a role in counterproductive outcomes such as exacerbation of health anxiety (Starcevic and Berle 2013; te Poel et al. 2016; Muse et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2016; Fergus 2013).

Starcevic and Berle (2013) suggest that obsessive–compulsive symptoms are, too, relevant for cyberchondria. Various empirical studies have supported this assertion with results showing moderate correlations between cyberchondria and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Fergus 2014; Fergus and Russell 2016; Norr et al. 2015a; Bajcar et al. 2019). Individuals experiencing health-related obsessional thoughts like overestimating the harmfulness of benign health symptoms, fearing serious illness and experiencing feelings of urgency to attain health-related reassurance might display a tendency toward cyberchondria (Norr et al. 2015a; Fergus 2014). It is likely that individuals with obsessive–compulsive symptoms would excessively search for medical content with the aim of reducing the severity of intrusive and unwanted thoughts, and trying to prevent anticipated illness. Such behaviors may be interpreted as attempts of obtaining allegedly comforting health-related data in order to reclaim a sense of safety and control (Halldorsson and Salkovskis 2017; Norr et al. 2015a; Fergus and Russell 2016).

Both, health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms are sometimes referred to as “chronic disorders of control” (Starcevic 1990 p. 346), denoting mainly the difficulty in dealing with ambiguity and uncertainty (Deacon and Abramowitz 2008). Some authors claim that health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms stem from the shared pattern of intrusive thoughts and repetitive and purposeful behaviors and belong to one broad spectrum of obsessive–compulsive disorders (Abramowitz 2005; Abramowitz and Braddock 2006; Solem et al. 2015). Others however, indicate that the two constructs are distinct due to differences in evaluating obsessive thoughts and behavioral reactions upon their occurrence (Starcevic 2014; Hedman et al. 2017). Health anxious individuals tend to treat their symptoms as authentically threatening and accept their thoughts about illness as relevant. They often experience urges to seek medical consultation to get reassured about good health or to cure the presumed disease. In contrast, obsessive–compulsive symptoms are often perceived as unfounded and senseless and sometimes are being resisted by an individual (Starcevic 2014; for review). Recent research on cyberchondria indicated moderate to relatively high correlations among health anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms and cyberchondria, however there is still meaningful amount of non-overlapping variance between these constructs (Fergus and Russell 2016; Norr et al. 2015a; Mathes et al. 2018).

Cyberchondria: The Role of Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is defined as the assessment of the self-worth (Rosenberg 1965). Individuals with low self-esteem hold negative beliefs about the self, i.e., they perceive themselves to be less appealing, incompetent, dull, and less worthy than others. Low self-esteem is associated with various psychopathology (Silverstone and Salsali 2003; Donnellan et al. 2005), and addictions (Silverstone 1991; Rizwan and Ahmad 2015). According to the vulnerability model, low self-esteem is considered a vulnerability factor for psychological dysfunctions, whereas scar model assumes that various psychopathology may downgrade self-esteem (Silverstone 1991; Zeigler-Hill 2011). There seems to be a consensus that low self-esteem is bidirectionally related to psychopathology. Various studies demonstrated close associations of self-esteem with health anxiety (Marcus 1999; Noyes et al. 2005; Starcevic 1990; Watson and Pennebaker 1989; Hollifield et al. 1999). Apparently, individuals with low self-esteem tend to experience increased health anxiety, and often confuse somatic symptoms with real and serious physical illness (Marcus 1999; Silverstone 1991; Fennell 1997; Rizwan and Ahmad 2015). Self-esteem has also been proposed as an antecedent (Fava et al. 1996) or co-occurring factor of obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Ehntholt et al. 1999; Husain et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2006). Individuals with low self-esteem often experience dysfunctional cognitions such as catastrophic interpretations of intrusive thoughts, exaggerated feelings of responsibility for harm and compulsive behaviors (Salkovskis 1989, 1999).

The extant literature suggests that low self-esteem is a risk factor for Internet-related problems, such as spending too much time online (Armstrong et al. 2000), difficulty controlling Internet usage (Widyanto and Griffith 2011), problematic Internet use (Bulut Serin 2011; Durak and Senol-Durak 2014; Kim and Davis 2011; Mei et al. 2016), pathological Internet use (Niemz et al. 2005; Sideli et al. 2017), and even Internet addiction (Tsai et al. 2009; Aydin and Sari 2011; Bozoglan et al. 2013; Ivanova 2013; Błachnio et al. 2016). Probably individuals with negative self-beliefs perceive anonymous online “medical consultation” as a psychologically more comfortable mode of addressing health concerns than a face-to-face appointment with a physician. Visits to a doctor often involve a critical appraisal of the diagnosis and give the patient an opportunity to ask questions, which are fairly challenging tasks for people with low self-esteem. It is thus possible that individuals with low self-esteem are more likely to choose the virtual reality of the Internet for a diverse array of purposes, including excessive checking of health-related content, than people with a stable self-concept. Consequently, individuals with low self-esteem may become susceptible to cyberchondria as a specific type of PIU expressed in a reduced ability to control Internet use (Fergus and Dolan 2014; Fergus and Spada 2017). To our knowledge, only one study (Ivanova 2013) reported the non-significant relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria, measured by a few items following White and Horvitz’s (2009) procedure.

The Present Study

Considering low self-esteem a potential risk factor for health anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and PIU, one might speculate that it would also be linked to cyberchondria. We thus aimed to examine the direct relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria, and the mediating role of health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria.

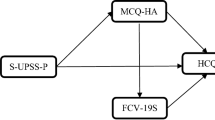

Considering cyberchondria as a specific health-related PIU (Fergus and Dolan 2014; Fergus and Spada 2017) and based on the previous empirical results concerning the relationship between self-esteem and PIU (e.g. Armstrong et al. 2000; Kim and Davis 2011; Mei et al. 2016; Widyanto and Griffith 2011), we hypothesized that low self-esteem would be related to high levels of cyberchondria (H1). Also, we hypothesized that the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria would be mediated by health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (H2). Our assumptions were based on previous findings referring to: 1) the relationships between self-esteem, and health anxiety (e.g. Marcus 1999; Hollifield et al. 1999), and between self-esteem and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (e.g. Fava et al. 1996; Ehntholt et al. 1999); 2) the associations of health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms with cyberchondria (Fergus 2014; Fergus and Russell 2016; Norr et al. 2015a; Bajcar et al. 2019). It should be emphasized that, despite revealed low to moderate correlations between health anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms and cyberchondria, these constructs do not overlap with each other and are considered distinct (e.g. Fergus and Russell 2016). We thus assumed self-esteem to operate on cyberchondria through parallel mechanisms embracing dysfunctional cognitions and behaviors related to health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. It seems justified to examine an integrated pattern of relationships between self-esteem and cyberchondria with health anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms as mediators (Fig. 1).

When examining mediation using cross-sectional data, the direction of effects is somewhat unclear. According to empirical evidence mentioned earlier, various psychopathology might have a negative effect on self-esteem (see Zeigler-Hill 2011). It is thus possible that cyberchondria predicts self-esteem directly as well as through health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. We therefore tested the reverse parallel mediation model of the relationship between cyberchondria and self-esteem with the same mediators.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Power analysis indicated a desired sample size of 119, anticipating a medium effect size (Cohen’s f2 = .15), power of .80, and p = .05 (Cohen 1992; Faul et al. 2007). Considering these requirements, the study was conducted among 214 Polish adults. Participants were recruited from a community sample using a snowball method. The inclusion criteria were: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) computer skills (3) use of the Internet; (4) unrestricted access to the Internet; (5) literacy (individuals who signaled difficulties in reading or interpreting questions were excluded from the study). All participants were informed about the nature of the study and assured that their responses to the study questions will remain confidential. The study was cross-sectional, but data were collected in two sessions separated by a two-week interval to avoid common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). All respondents provided informed consent to participate in the study. They participated on a voluntary basis and did not receive any financial reward. Seven individuals were excluded from the analysis because they did not complete all measures. Thus, a final sample consisted of 207 (122 women and 85 men) aged 19–64 years old (M = 31.47, Mdn = 28, SD = 13.02).

Measures

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg 1965)

Self-esteem was measured with the Polish version (Dzwonkowska et al. 2007) of the RSES, a 10-item measure of self-esteem (e.g. “On the whole, I feel satisfied with life”) with a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. Cronbach’s alpha was .86 in the current study.

The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS-PL; Bajcar et al. 2019)

To measure cyberchondria, the Polish adaptation of the 33-item Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS; McElroy and Shevlin 2014) was used. Some authors (e.g. Fergus 2014; Norr et al. 2015b) recommend omitting the three-item scale which measures a presumably distinct construct of mistrust of medical professional, and endorse 30 items to measure cyberchondria. Following these recommendations and due to strong intercorrelations between the four dimensions of CSS we decided to use cyberchondria total score as a sum of 30-item four CSS-PL subscales: Compulsions (e.g. “Researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online interrupts my online leisure activities (e.g. streaming movies)”), Distress (e.g. “I have trouble relaxing after researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online”), Excessiveness (e.g. “I read different web pages about the same perceived condition”), and Reassurance (e.g. “I discuss my online medical findings with my GP/health professional”). Participants rated all statements on the 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The range of total score from 30 to 150. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the cyberchondria total score was high (α = .95).

The Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI; Salkovskis et al. 2002)

Health anxiety was measured with the Polish version of SHAI (Kocjan 2016), which consists of 18 items related to health anxiety (e.g. “I spend much of my time worrying about my health”). Following the recommendations from the literature (Alberts et al. 2013) we used the illness likelihood subscale (14 items) of the SHAI to measure health anxiety. Four answers (rated from 0 to 3) express an increase in health anxiety; a higher score represents a higher degree of health anxiety. In this study, the SHAI total score was adequately reliable (α = .85).

The Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms Scale (DOCS; Abramowitz et al. 2010)

Obsessive–compulsive symptoms were assessed with the Dimensional Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (DOCS; Abramowitz et al. 2010), which consists of 20 symptoms in four dimensions: Contamination, Responsibility, Unacceptable Thoughts, and Symmetry. Within each dimension, the following parameters of severity were assessed: (a) time occupied by obsessions and compulsions, (b) avoidance behavior, (c) distress, (d) functional interference, and (e) difficulty controlling each symptom. Participants rated on a scale from 0 (not at all bothered) to 4 (bothered a lot) their experiences from the last six months (e.g. “About how much time have you spent each day thinking about contamination and engaging in washing or cleaning behaviors because of contamination?”). The total score of DOCS expresses the level of obsessive–compulsive symptoms. The reliability of DOCS measure in this study was high (α = .93).

Analytical Approach

Data analysis was performed with SPSS 24.0, including PROCESS macros provided by Hayes (2013). Descriptive statistics were computed for the main study variables and bivariate relations tested with Pearson correlations. To conduct preliminary verification of the hypotheses, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. Age and gender were entered as controlled variables in the first step of the regression. In step 2 self-esteem (as a predictor), and in step 3 health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (as mediators) were entered to the regression model of cyberchondria. Next, we tested a parallel mediation model (Hayes 2013; model 4) to assess the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria through health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (see Fig. 1). Parallel mediation analysis was also conducted to examine reverse relationships between cyberchondria and self-esteem with the same mediators. We also controlled for age, which was added to the analysis as a covariate. Following Hayes (2013) recommendations, in the mediation model we tested the following relationships: 1) between the predictor variable and the mediators (a1, a2); 2) between mediators and the outcome variable (b1, b2); 3) the total (c), and direct effect of the predictor on the outcome variable controlling for mediators (c’); 4) the indirect effect of the predictor on the outcome variable through the mediators (see Fig. 1). Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05 if the 95% bootstrapped confidence interval (10,000 resamples) of the indirect effect did not contain zero (Hayes 2013). Following the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991), all continuous variables were standardized to a z-score.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, reliability, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for all measured variables. Cyberchondria was negatively associated with health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Self-esteem was also negatively correlated with cyberchondria, health anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. All variables tested in the mediation models were significantly interrelated.

In the MLR model, the order of entry was as follows. Step 1 showed non-significant effect of gender and a negative effect of age on cyberchondria (b = −.17, SE = .01, p = .017; b = −.07, SE = .14, p = .34, respectively), explaining 3% of the variance. In step 2, self-esteem predicted significantly cyberchondria (b = −.22, SE = .07, p < .001), explaining an additional 5% of the variance. In step 3, obsessive–compulsive symptoms and health anxiety had significant effects on cyberchondria (b = .37, SE = .07, p < .001, b = .41, SE = .07, p < .001, respectively), explaining a total of 22% of variance. The overall regression model explained 31% of the total variance (F[5, 202] = 17.54, p < .001).

Main Mediation Model

Next, we conducted a multiple mediation analysis to investigate whether health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms mediate the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. We controlled only the effect of age due to the non-significant effect of gender in the preliminary analysis. We found no main effect for age (b = −.01, SE = .06, p = .90) as a covariate. There was a significant negative effect of self-esteem on health anxiety (a1: b = −.34, SE = .06, p < .001), and on obsessive–compulsive symptoms (a2: b = −.33, SE = .06, p < .001). In addition, health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms were significantly related to cyberchondria (b1: b = .41, SE = .07, p < .001; b2: b = .19, SE = .07, p = .007, respectively). The total effect of self-esteem on cyberchondria was significant (c: b = −.23, SE = .07, p = .001) (see Fig. 2), and after entering health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms to the model, the direct effect of self-esteem on cyberchondria became non-significant (c’: b = −.02, SE = .07, p = .71). Using the bootstrapping procedure (10,000 resamples), the analysis showed that the total indirect effect of self-esteem on cyberchondria through health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms was significant (effect = −.20, boot SE = .05, boot 95% CI [−.32, −.12]), indicating full mediation. The indirect effects of both mediators were also significant (health anxiety: effect = −.14, boot SE = .04, boot 95% CI [−.32, −.12]; obsessive–compulsive symptoms: effect = −.06, boot SE = .04, boot 95% CI [−.13, −.02]). The analysis of contrast between specific indirect effects (Hayes 2013) indicated no significant difference between indirect effects via health anxiety and indirect effect via obsessive–compulsive symptoms (c1 = −.07, SE = .05, 95% CI [−.19, .02]). The overall model explained 30% of the total variance in cyberchondria (F[4, 202] = 22.04, p < .001).

Reverse Mediation Model

To examine the reverse relationship between cyberchondria and self-esteem, we also conducted multiple mediation analysis with health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms as potential mediators (see Fig. 3). In the tested model cyberchondria was significantly related to health anxiety (a1: b = .50, SE = .06, p < .001), and to obsessive–compulsive symptoms (a2: b = .37, SE = .06, p < .001). Moreover, health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms had a positive significant effect on self-esteem (b1: b = −.21, SE = .08, p < .001; b2: b = −.24, SE = .08, p = .002). The total effect of cyberchondria on self-esteem was significant (c: b = −.22, SE = .07, p = .001). After entering both mediators to the model, the direct effect of cyberchondria on self-esteem was reduced to non-significance (c’: b = −.03, SE = .08, p = 71). The total indirect effect of cyberchondria on self-esteem via health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms was significant (effect = −.19, boot SE = .04, boot 95% CI [−.29, −.11]), indicating full mediation. The indirect effects of both mediators were also significant (health anxiety: effect = −.11, SE = .04, 95% CI [−.20, −.03]; obsessive–compulsive symptoms: effect = −.09, boot SE = .03, boot 95% CI [−.15, −.04]). The differences between indirect effect via health anxiety and indirect effect via obsessive–compulsive symptoms were not significant (c1 = .02, boot SE = .06, boot 95% CI [−.09, .13]). The tested model explained 20% of the variance (F[4, 202] = 12.62, p < .001), and did not obtain a significant effect of age as covariate (b = .10, SE = .07, p = 12).

Discussion

First, the aim of our study was to examine the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. We found a direct negative relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria, supporting H1. This result implies that low self-esteem leads to higher cyberchondria considered as a specific health-related PIU (Fergus and Dolan 2014; Fergus and Spada 2017). It corresponds to previous findings, that self-esteem may be viewed as a predictor variable for problematic or pathological Internet use (Armstrong et al. 2000; Durak and Senol-Durak 2014; Widyanto and Griffith 2011; Kim and Davis 2011) or Internet addiction (Tsai et al. 2009; Aydin and Sari 2011; Bozoglan et al. 2013; Błachnio et al. 2016; Ivanova 2013). Our results suggest that individuals with low self-esteem may have problems with uncontrollable and excessive behaviors related to various activities within Internet, like repetitive checking health-related information, assessing somatic symptoms, comparing data through recurrent verification of content. Consequently, low self-esteem may result in becoming susceptible to cyberchondria as a specific type of PIU, expressed in a reduced ability to control Internet use (Fergus and Dolan 2014; Fergus and Spada 2017). We thus propose considering self-esteem as one of the potential predictors of cyberchondria. It should be emphasized that although the variance explained by self-esteem in cyberchondria was not large (5%), it was statistically significant. In sum, one might expect that factors accounting for various forms of PIU might relate to cyberchondria as well. In future studies, self-esteem should not be overlooked in the explanation of cyberchondria.

Second, we examined the mediating role of health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. Our results indicated that low self-esteem predicts cyberchondria through health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms parallelly, supporting H2. This is consistent with previous proposals and empirical findings related to negative relationship between self-esteem and health anxiety (Marcus 1999; Noyes et al. 2005; Starcevic 1990; Watson and Pennebaker 1989; Hollifield et al. 1999) and between health anxiety and cyberchondria (McMullan et al. 2019). Individuals with dysfunctional self-beliefs might be more prone to activate erroneous cognitions about health and produce negative interpretation of even neutral stimuli related to health e.g. physical symptoms of a common cold. This could lead to engaging in seeking reassurance through excessive and repeated health-related Internet searching i.e., cyberchondria (Fergus 2013, 2015). At the same time, our results complement the existing body of knowledge about the relationship between self-esteem and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Fava et al. 1996; Ehntholt et al. 1999; Husain et al. 2014), and associations of obsessive–compulsive symptoms with cyberchondria (Fergus 2014; Norr et al. 2015a; Fergus and Russell 2016; Bajcar et al. 2019). They imply that individuals with low self-esteem may experience obsessive thoughts (i.e., negative cognitions about own health), and compulsions (i.e., poorly-controlled excessive searching for medical information on the Internet) which in turn increase the possibility of cyberchondriac behaviors. Presented direction of the relationships corresponds to the vulnerability model of self-esteem, in which low self-esteem is considered a risk factor for psychopathology (Zeigler-Hill 2011).

Following assumptions on the distinctiveness of health anxiety from obsessive–compulsive symptoms (e.g. Starcevic 2014; Hedman et al. 2017) our results indicated that these two constructs parallelly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. We therefore speculated that two different mechanisms were responsible for these mediated relationships. Presumably individuals with low self-esteem who therefore might suffer from health anxiety, may in consequence become vulnerable to experiencing cognitive-affective domains of cyberchondria (e.g. distress), while individuals with low self-esteem struggling with obsessive–compulsive symptoms may be predisposed to cognitive-behavioral part of cyberchondria (e.g. distress, reassurance seeking compulsions and excessiveness). Possibly, anxious and obsessive thinking about health (present in both, health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms), stimulate reassurance-seeking behaviors and compulsive checking, which function as safety measures taken to alleviate health concerns. Although the current study demonstrated the full mediation effect of the two variables, it is possible that other psychological factors like self-confidence, locus of control, intolerance of uncertainty, or vulnerability to social influence mediate the relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. However, these assumptions require further investigation.

In this study, we also examined the potential for a reverse direction in the relationships between the tested variables, finding cyberchondria to be negatively and directly linked to self-esteem. It is possible that cyberchondria serves as a predictive variable of low self-concept. Such reasoning can be justified based on earlier findings that fear of illness may interfere with stable feelings of self-worth (Marcus 1999). This result aligns with more general findings on the negative relationship of PIU with overall well-being, particularly self-esteem and life satisfaction (Mei et al. 2016; Çikrıkci 2016). In our study, the reverse relationship between cyberchondria and self-esteem was also mediated by health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Possibly then, cyberchondria precedes feelings of health anxiety, obsessive thoughts about health, and uncontrollable behaviors, which altogether negatively relate to self-esteem. Described effects support White and Horvitz’s (2009) findings that almost 40% of those who are confronted with health-related information online become distressed and anxious, but surprisingly continue the health-related online search.

Presented results are consistent with previous considerations about the possible reciprocal relationship between cyberchondria and: (i) health anxiety (te Poel et al. 2016; Fergus 2013; Starcevic and Berle 2013; Singh et al. 2016; Muse et al. 2012), and (ii) obsessive–compulsive problems (Norr et al. 2015a; Fergus and Russell 2016). Also, the associations between health anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and self-esteem are in line with existing findings that self-concept may be downgraded by health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Marcus 1999; Fava et al. 1996; Silverstone 1991). In short, excessive searching for medical information may increase health anxiety and reinforce compulsive seeking behavior, which in turn leaves an individual with feelings of worthlessness, most probably due to fear of unresolved health issues. These results correspond to the scar model, indicating that relevant information about the self may become distorted as a consequence of psychopathology (Zeigler-Hill 2011). As suggested by Starcevic and Berle (2013) and empirically verified by te Poel et al. (2016), cyberchondria, health anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive symptoms may be reciprocally related, creating an interdependent response “loop” mechanism. In addition, the bidirectional relationship between cyberchondria and self-esteem sheds light on the potential role of cyberchondria in psychological well-being. Due to correlational nature of our study we avoided drawing conclusions about the causal relationships among tested variables. Causality could be presumed upon longitudinal study, in which self-esteem and cyberchondria would be measured twice in two different time points (T1 and T3) and health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in yet another time-point (T2).

The results also provide insights into the relationship between demographic variables and cyberchondria. In the preliminary analysis, there was no effect of gender, but a significant negative effect of age on cyberchondria. However, in the test of the mediation model, age as a covariate was non-significant. These results suggest that behaviors related to cyberchondria appear to be more prevalent among younger people. We speculate that younger adults are more likely to have unlimited access to the Internet and use it frequently. Individuals with low self-esteem who go online to seek information (including medical) may be more vulnerable to online searching for health-related information (Widyanto and Griffith 2011). However, further research is needed to investigate the effect of age on health-related Internet searching.

This study, although exploratory, contribute to the growing body of knowledge on the association between self-esteem and excessive health-related Internet use in healthy adults with unrestricted access to the Internet. Presented outcomes are consistent with previous results, suggesting that low self-esteem is a vulnerability factor for PIU (Armstrong et al. 2000; Durak and Senol-Durak 2014; Mei et al. 2016; Kim and Davis 2011), health anxiety (Marcus 1999; Noyes et al. 2005), and obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Fava et al. 1996; Ehntholt et al. 1999). Our findings indicate that low self-esteem may intensify people’s fear of becoming ill, bring about intrusive thoughts and uncontrollable acts, which together may lead to excessive use of the Internet in a search for potentially comforting health-related information. However, future research will ascertain whether low self-esteem is related to cyberchondria as one of the Internet-related problems.

Implications

To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no specific therapies for cyberchondria. In the context of a cognitive–behavioral model our findings of relationships between self-esteem, health anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and cyberchondria shed light on a course for potential interventions. Cyberchondria embracing cognitive processes e.g. obsessive thoughts about health, and dysfunctional behaviors, such as health-related PIU may result in negative consequences in different areas of an individual’s life (Davis 2001). Given cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) to be an optimal intervention for cyberchondria’s correlates, i.e., low self-esteem (Fennell 1997; Waite et al. 2012), health anxiety (Olatunji et al. 2014; Cooper et al. 2017), obsessive–compulsive problems (Olatunji et al. 2013), and pathological Internet use (Davis 2001; Spada 2017), it is possible that CBT interventions suited for these disorders could also generate positive results for cyberchondria. It is likely that in the course of working on enhancing self-esteem, the risk for other psychiatric disorders might be lessened. Consequently, higher self-esteem might be related to lower cyberchondria, both directly and indirectly, through reducing general health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive problems.

Similar to previous findings, the current results imply a comorbidity of dysfunctions associated with cyberchondria. Possibly, cyberchondria together with other disorders might form a broader psychopathological syndrome. Treating these dysfunctions will potentially prevent the emergence of cyberchondria, and individually tailored CBT treatment could facilitate quicker recovery.

Based on the reverse relationship between cyberchondria and self-esteem, it might be possible that CBT interventions targeting Internet-related problems could bring desired results in treating cyberchondria as a type of excessive Internet use (Fergus and Dolan 2014). Confronting excessive Internet searches for health-related information might be beneficial in terms of enhancing self-worth, and reducing the possibility of clinical implications of cyberchondria (namely, health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms).

The reverse relationship between cyberchondria and self-esteem also implies that taking preventive measures against cyberchondria may help to reduce the risk of various mental disorders. From the individual perspective, enhancing users’ e-health literacy, would be both practical and advantageous for each and every Internet user (Norman and Skinner 2006). E-health service providers could play a special role in the prevention of cyberchondria through facilitating users’ understanding of content, providing warning about unreliable sources, and regulating provision of e-health information. On a system-wide scale, creating professional e-health services run by medical professionals, health-care system members, and government agencies might also prevent the emergence of cyberchondria (Robertson et al. 2014).

More research is needed to clarify which psychological disorders contribute to the emergence and maintenance of cyberchondria. Before determining the direction of cyberchondria therapy, it is necessary to detect the severity of its symptoms. The diagnosis of non-psychological variables, such as age, gender, Internet accessibility, and time devoted to online activities should also be controlled. Finally, changes in both Internet content and Internet literacy shall be monitored, as these may exacerbate cyberchondriac behaviors.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study offers new and interesting results, it has a few limitations that need to be noted. First, the data were collected from a non-clinical population through the use of self-report instruments. Consequently, the results cannot be generalized upon the clinical groups. Furthermore, the design of this study was cross-sectional so in order to draw conclusions on causal effects among tested variables longitudinal research (starting in adolescence) is needed. Moreover, the reciprocal relationship between the tested variables raise the question of whether cyberchondria is a new dysfunction or just a new term for the coexistence of already identified constructs, i.e., PIU, health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive problems. Also, viewing cyberchondria as an abnormal behavioral pattern provoking distress and anxiety, there is a need for studying personal contingencies, like intolerance of uncertainty, which may contribute to the development or maintenance of this condition.

Lastly, on average, the study’s participants were relatively young and did not demonstrate high levels of cyberchondria. Therefore, further research is required with a larger, more heterogeneous group of participants, to appraise for differences in relationships between the level of cyberchondria and potential detrimental consequences.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study enables deeper understanding of the cyberchondria phenomenon and its dispositional correlates. The results indicate a direct relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria. Moreover, self-esteem is related to cyberchondria via health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. In addition, in the reverse mediation model, cyberchondria was significantly related to self-esteem. This relationship was also parallelly mediated by health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. The findings of this study contribute to the body of knowledge indicating that individuals with low self-esteem, health anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive symptoms may be more vulnerable to experiencing cyberchondria. The bidirectional relationship between self-esteem and cyberchondria via health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms potentially create the “loop”, in which an individual with low self-esteem may be more vulnerable to excessive searching of health-related information on the Internet, which in consequence may lead to worsening of self-regard. It is reasonable to suggest that cyberchondria relates to various psychopathology, which require relevant intervention. Intervention programs for cyberchondria could be addressed through CBT, which has been established as effective in the treatment of low self-esteem, health anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and PIU. Enhancing e-literacy and educating Internet users on the skillful selection of reliable data sources would seem to be the primary preventive techniques in curbing the detrimental effects of cyberchondria.

References

Abramowitz, J. S. (2005). Health anxiety: Conceptualization, treatment, and relationship to obsessive–compulsive disorder. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 17, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401230500295339.

Abramowitz, J. S., & Braddock, A. E. (2006). Hypochondriasis: Conceptualization, treatment, and relationship to obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29, 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2006.02.008.

Abramowitz, J. S., Deacon, B., Olatunji, B., Wheaton, M. G., Berman, N., Losardo, D., & Hale, L. R. (2010). Assessment of obsessive–compulsive symptom dimensions: Development and evaluation of the dimensional obsessive–compulsive scale. Psychological Assessment, 22, 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018260.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Alberts, N. M., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Jones, S. L., & Sharpe, D. (2013). The short health anxiety inventory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.10.009.

Armstrong, L., Phillips, J. G., & Saling, L. L. (2000). Potential determinants of heavier internet usage. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53, 537–550.

Aydin, B., & Sari, S. V. (2011). Internet addiction among adolescents: The role of self-esteem. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 3500–3505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.325.

Bajcar, B., Babiak, J., & Olchowska-Kotala, A. (2019). Cyberchondria and its measurement. The Polish adaptation and psychometric properties of Cyberchondria Severity Scale CSS-PL. Polish Psychiatry, 53(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/81799.

Baumgartner, S. E., & Hartmann, T. (2011). The role of health anxiety in online health information search. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14, 613–618. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0425.

Błachnio, A., Przepiórka, A., Senol-Durak, E., Durak, M., & Sherstyuk, L. (2016). The role of personality traits in Facebook and internet addictions: A study on polish, Turkish, and Ukrainian samples. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.037.

Bozoglan, B., Demirer, V., & Sahin, I. (2013). Loneliness, self-esteem, and life satisfaction as predictors of internet addiction: A cross-sectional study among Turkish university students. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 54, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12049.

Bulut Serin, N. (2011). An examination of predictor variables for problematic Internet use. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 10, 54–62.

Çikrıkci, O. (2016). The effect of Internet use on well-being: Meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 560–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.021.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Cooper, K., Gregory, J. D., Walker, I., Lambe, S., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2017). Cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 45, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465816000527.

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8.

Deacon, B., & Abramowitz, J. S. (2008). Is hypochondriasis related to obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, or both? An empirical evaluation. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 22, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.22.2.115.

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16(4), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x.

Durak, M., & Senol-Durak, E. (2014). Which personality traits are associated with cognitions related to problematic Internet use? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 206–218.

Durak-Batigun, A., Gor, N., Komurcu, B., & Senkal-Erturk, I. (2018). Cyberchondria Scale (CS): Development, validity and reliability study. Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 31, 148–162. https://doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN2018310203.

Dzwonkowska, I., Lachowicz-Tabaczek, K., & Łaguna, M. (2007). Samoocena i jej pomiar. Polska adaptacja skali SES M. Rosenberga. Podręcznik. [Self-esteem and its measurement. Polish adaptation of M. Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale SES. Manual]. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych.

Ehntholt, K. A., Salkovskis, P. M., & Rimes, K. A. (1999). Obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and self-esteem: An exploratory study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 771–781.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Fava, G. A., Savron, G., Rafanelli, C., Grandi, S., & Canestrari, R. (1996). Prodromal symptoms in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychopathology, 29, 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1159/000284981.

Fennell, M. J. V. (1997). Low self-esteem: A cognitive perspective. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800015368.

Fergus, T. A. (2013). Cyberchondria and intolerance of uncertainty: Examining when individuals experience health anxiety in response to Internet searches for medical information. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16, 735–739. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0671.

Fergus, T. A. (2014). The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS): An examination of structure and relations with health anxiety in a community sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.05.006.

Fergus, T. A. (2015). Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as potential risk factors for cyberchondria: A replication and extension examining dimensions of each construct. Journal of Affective Disorders, 184, 305–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.017.

Fergus, T. A., & Dolan, S. L. (2014). Problematic Internet use and Internet searches for medical information: The role of health anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17, 761–765. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0169.

Fergus, T. A., & Russell, L. H. (2016). Does cyberchondria overlap with health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms? An examination of latent structure and scale interrelation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 38, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.01.009.

Fergus, T. A., & Spada, M. M. (2017). Cyberchondria: Examining relations with problematic Internet use and metacognitive beliefs. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24, 1322–1330. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2102.

Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Craig, K. D., & Hadjistavropoulos, T. (1998). Cognitive and behavioural responses to illness information: The role of health anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 149–164.

Halldorsson, B., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2017). Why do people with OCD and health anxiety seek reassurance excessively? An investigation of differences and similarities in function. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41, 619–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9826-5.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hedman, E., Ljótsson, B., Axelsson, E., Andersson, G., Rück, C., & Andersson, E. (2017). Health anxiety in obsessive compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in severe health anxiety: An investigation of symptom profiles. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 45, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.11.007.

Hollifield, M., Tuttle, L., Paine, S., & Kellner, R. (1999). Hypochondriasis and somatization related to personality and attitudes toward self. Psychosomatics, 40, 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2012.02.002.

Husain, N., Chaughry, I., Raza-ur-Rehman, & Ahmed, G. R. (2014). Self-esteem and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 64, 64–68.

Ivanova, E. (2013). Internet addiction and cyberchondria—their relationship with well-being. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 1, 57–70.

Kim, H.-K., & Davis, K. E. (2011). Toward a comprehensive theory of problematic Internet use: Evaluating the role of self-esteem, anxiety, flow, and the self-rated importance of Internet activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 490–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.11.001.

Kobori, O., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2012). Patterns of reassurance seeking and reassurance-related behaviours in OCD and anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 41, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465812000665.

Kocjan, J. (2016). Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) - Polish version: Evaluation of psychometric properties and factor structure. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 3, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/64276.

Laconi, S., Vigouroux, M., Lafuente, C., & Chabrol, H. (2017). Problematic internet use, psychopathology, personality, defense and coping. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.025.

Marcus, D. K. (1999). The cognitive-behavioral model of hypochondriasis: Misinformation and triggers. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 47, 79–91.

Mathes, B. M., Norr, A. M., Allan, N. P., Albanese, B. J., & Schmidt, N. B. (2018). Cyberchondria: Overlap with health anxiety and unique relations with impairment, quality of life, and service utilization. Psychiatry Research, 261, 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.002.

McElroy, E., & Shevlin, M. (2014). The development and initial validation of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.007.

McMullan, R. D., Berle, D., Arnáez, S., & Starcevic, V. (2019). The relationships between health anxiety, online health information seeking, and cyberchondria: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.037.

Meerkerk, G. J., Van Den Eijnden, R. J. J., Vermulst, A. A., & Garretsen, H. F. L. (2009). The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 12(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181.

Mei, S., Yau, Y. H., Chai, J., Guo, J., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Problematic Internet use, well-being, self-esteem and self-control: Data from a high-school survey in China. Addictive Behaviors, 61, 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.009.

Muse, K., McManus, F., Leung, B., Meghreblian, T., & Williams, J. M. G. (2012). Cyberchondriasis: Fact or fiction? A preliminary examination of the relationship between health anxiety and searching for health information on the Internet. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.11.005.

Niemz, K., Griffiths, M., & Banyard, P. (2005). Prevalence of pathological Internet use among university students and correlations with self-esteem, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), and disinhibition. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8, 562–570. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.562.

Norman, C. D., & Skinner, H. A. (2006). eHealth literacy: Essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8, E9. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8.2.e9.

Norr, A. M., Allan, N. P., Boffa, J. W., Raines, A. M., & Schmidt, N. B. (2015a). Validation of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS): Replication and extension with bifactor modeling. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 31, 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.001.

Norr, A. M., Oglesby, M. E., Raines, A. M., Macatee, R. J., Allan, N. P., & Schmidt, N. B. (2015b). Relationships between cyberchondria and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Psychiatry Research, 230, 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.034.

Noyes, R., Jr., Watson, D. B., Letuchy, E. M., Longley, S. L., Black, D. W., Carney, C. P., & Doebbeling, B. N. (2005). Relationship between hypochondriacal concerns and personality dimensions and traits in a military population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193, 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000152794.87100.92.

Olatunji, B. O., Davis, M., Powers, M., & Smits, J. (2013). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.020.

Olatunji, B. O., Kauffman, B. Y., Meltzer, S., Davis, M. L., Smits, J. A. J., & Powers, M. B. (2014). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for hypochondriasis/health anxiety: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.002.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Rizwan, M., & Ahmad, R. (2015). Self-esteem deficits among psychiatric patients. SAGE Open, 5, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015581649.

Robertson, N., Polonsky, M., & McQuilken, L. (2014). Are my symptoms serious Dr Google? A resource-based typology of value co-destruction in online self-diagnosis. Australasian Marketing Journal, 22, 246–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2014.08.009.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and adolescent self-image. New York: Princeton University.

Salkovskis, P. M. (1989). Cognitive-behavioural factors and the persistence of intrusive thoughts in obsessional problems. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 677–682.

Salkovskis, P. M. (1999). Understanding and treating obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 29–52.

Salkovskis, P. M., & Warwick, H. M. C. (2001). Making sense of hypochondriasis: A cognitive theory of health anxiety. In G. J. G. Asmundson, S. Taylor, & B. J. Cox (Eds.), Health anxiety: Clinical and research perspective on hypochondriasis and related conditions (pp. 46–64). New York: Wiley.

Salkovskis, P. M., Rimes, K. A., Warwick, H. M., & Clark, D. (2002). The health anxiety inventory: Development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychological Medicine, 32, 843–853. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702005822.

Selvi, Y., Turan, S. G., Sayin, A. A., Boysan, M., & Kandeger, A. (2018). The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS): Validity and reliability study of the Turkish version. Sleep and Hypnosis: A Journal of Clinical Neuroscience and Psychopathology, 20, 241–246. https://doi.org/10.5350/Sleep.Hypn.2018.20.0157.

Shapira, N. A., Lessig, M. C., Goldsmith, T. D., Szabo, S. T., Lazoritz, M., Gold, M. S., & Stein, D. J. (2003). Problematic Internet use: Proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depression and Anxiety, 17, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10094.

Sideli, L., La Cascia, C., Sartorio, C., Tripoli, G., Mulè, A., Taffaro, L., Ruggirello, I., Mangiapane, D., Piro, E., Inguglia, M., & La Barbera, D. (2017). Internet out of control: The role of self-esteem and personality traits in pathological Internet use. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 14, 88–93.

Silverstone, P. H. (1991). Low self-esteem in different psychiatric conditions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30, 185–188.

Silverstone, P. H., & Salsali, M. (2003). Low self-esteem and psychiatric patients: Part 1-the relationship between low self-esteem and psychiatric diagnosis. Annals of General Hospital Psychiatry, 2, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2832-2-2.

Singh, K., Fox, J., & Brown, R. (2016). Health anxiety and Internet use: A thematic analysis. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 10, article 4. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2016-2-4.

Solem, S., Borgejordet, S., Haseth, S., Hansen, B., Håland, Å., & Bailey, R. (2015). Symptoms of health anxiety in obsessive–-compulsive disorder: Relationship with treatment outcome and metacognition. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 5, 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2015.03.002.

Spada, M. M. (2017). An overview of problematic Internet use. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.007.

Starcevic, V. (1990). Relationship between hypochondriasis and obsessive–compulsive personality disorder: Close relatives separated by nosological schemes? American Journal of Psychotherapy, 44, 340–347.

Starcevic, V. (2014). Boundaries and overlap between hypochondriasis and other disorders: Differential diagnosis and patterns of co-occurrence. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 10(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573400509666131119011010.

Starcevic, V. (2017). Cyberchondria: Challenges of problematic online searches for health-related information. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86, 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1159/000465525.

Starcevic, V., & Berle, D. (2013). Cyberchondria: Towards a better understanding of excessive health-related Internet use. Expert Reviews of Neurotherapeutics, 13, 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.12.162.

Starcevic, V., & Berle, D. (2015). Cyberchondria: An old phenomenon in a new guise? In E. Aboujaoude & V. Starcevic (Eds.), Mental health in the digital age: Grave dangers, great promise (pp. 106–117). New York: Oxford University Press.

te Poel, F., Baumgartner, S. E., Hartmann, T., & Tanis, M. (2016). The curious case of cyberchondria: A longitudinal study on the reciprocal relationship between health anxiety and online health information seeking. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.07.009.

Tsai, H. F., Cheng, S. H., Yeh, T. L., Shih, C. C., Chen, K. C., Yang, Y. C., & Yang, Y. K. (2009). The risk factors of Internet addiction – A survey of university freshmen. Psychiatry Research, 167, 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.015.

Waite, P., McManus, F., & Shafran, R. (2012). Cognitive behaviour therapy for low self-esteem: A preliminary randomized controlled trial in a primary care setting. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43, 1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.04.006.

Warwick, H. N., & Salkovskis, P. M. (1990). Hypochondriasis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(2), 105–117.

Watson, D., & Pennebaker, J. (1989). Health complaints, stress, and distress: Exploring the central role of negative affectivity. Psychological Review, 96, 234–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.234.

Weinstein, A., & Aboujaoude, E. (2015). A review of problematic internet use. In E. Aboujaoude & V. Starcevic (Eds.), Mental health in the digital age grave dangers, great promise (pp. 3–26). London: Oxford University Press.

White, R. W., & Horvitz, E. (2009). Cyberchondria: Studies of the escalation of medical concerns in web search. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 27, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/1629096.1629101.

Widyanto, L., & Griffith, M. D. (2011). An empirical study of problematic Internet use and self-esteem. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning, 1, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcbpl.2011010102.

Wu, K. D., Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (2006). Relations between obsessive–compulsive disorder and personality: Beyond axis I-axis II comorbidity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20, 695–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.11.001.

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1, 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237.

Zeigler-Hill, V. (2011). The connections between self-esteem and psychopathology. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 41, 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-010-9167-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bajcar, B., Babiak, J. Self-esteem and cyberchondria: The mediation effects of health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in a community sample. Curr Psychol 40, 2820–2831 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00216-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00216-x