Abstract

Background

Colonic diverticular disease is typically conceived as acute diverticulitis attacks surrounded by periods of clinical silence. However, evolving data indicate that many patients have persistent symptoms and diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) long after acute attacks. We developed a disease-targeted HRQOL measure for symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD)—the diverticulitis quality of life (DV-QOL) instrument.

Methods

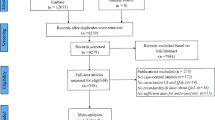

We conducted a systematic literature review to craft a conceptual model of SUDD HRQOL. This was complemented by three focus groups including 45 SUDD patients. We developed items based on our literature search, focus groups, and cognitive debriefings. We administered the items to SUDD patients with persistent symptoms following a confirmed diverticulitis event. We created scales based on factor analysis and evaluated the scales for reliability and validity.

Results

Concept elicitation revealed a range of illness experiences attributed to SUDD. Coding of 20,490 transcribed words yielded a 52-code network with four primary, condition-related concepts: (1) physical symptoms (e.g., bloating); (2) behaviors (e.g., restrictions); (3) cognitions and concerns (e.g., fear); and (4) impact and consequences (e.g., absenteeism, anxiety). Based on patient language, we developed the 17-item DV-QOL instrument. In a cross-sectional validation sample of 197 patients, DV-QOL discriminated between patients with recent versus distant diverticulitis events and correlated highly with Short Form 36 and hospital anxiety and depression scores.

Conclusions

Patients with SUDD attribute a wide range of negative psychological, social, and physical symptoms to their condition, both during and after acute attacks; DV-QOL captures these symptoms in a valid, reliable manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Everhart, J. E., & Ruhl, C. E. (2009). Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: Lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology, 136, 741–754.

Sandler, R. S., Everhart, J. E., Donowitz, M., et al. (2002). The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology, 122, 1500–1511.

Parks, T. G. (1975). Natural history of diverticular disease of the colon. Clinical Gastroenterology, 4, 53–69.

Stollman, N. H., & Raskin, J. B. (1999). Diagnosis and management of diverticular disease of the colon in adults. Ad Hoc Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 94, 3110–3121.

Kozak, L. J., DeFrances, C. J., & Hall, M. J. (2006). National hospital discharge survey: 2004 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital & Health Statistics, 13(2006), 1–209.

Etzioni, D. A., Mack, T. M., Beart, R. W, Jr, et al. (2009). Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998–2005: Changing patterns of disease and treatment. Annals of Surgery, 249, 210–217.

Jung, H. K., Choung, R. S., Locke, G. R, 3rd, et al. (2010). Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome is associated with diverticular disease: A population-based study. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 105, 652–661.

Humes, D. J., Simpson, J., Neal, K. R., et al. (2008). Psychological and colonic factors in painful diverticulosis. British Journal of Surgery, 95, 195–198.

Peery, A. F., Dellon, E. S., Lund, J., et al. (2012). Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology, 143(1179–87), e1–e3.

Tursi, A., & Papagrigoriadis, S. (2009). Review article: The current and evolving treatment of colonic diverticular disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 30, 532–546.

Cohen, E., Fuller, G., Bolus, R., et al. (2012, May). Evidence for post-diverticulitis irritable bowel syndrome (PDV-IBS): Longitudinal analysis reveals higher incidence of IBS in DV cases vs. controls. Poster presented at Digestive Disease Week, San Diego, CA.

Strate, L. L., Modi, R., Cohen, E., et al. (2012). Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: Evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 107, 1486–1493.

Horgan, A. F., McConnell, E. J., Wolff, B. G., et al. (2001). Atypical diverticular disease: Surgical results. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 44, 1315–1318.

Sopena, F., & Lanas, A. (2011). Management of colonic diverticular disease with poorly absorbed antibiotics and other therapies. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology, 4, 365–374.

Shahedi, K., Fuller, G., Bolus, R., et al. (2012, May). Progression from incidental diverticulosis to acute diverticulitis. Poster presented at Digestive Disease Week, San Diego, CA.

Tursi, A., Brandimarte, G., Giorgetti, G. M., et al. (2005). Assessment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in uncomplicated acute diverticulitis of the colon. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 11, 2773–2776.

Barbara, G., De Giorgio, R., Stanghellini, V., et al. (2002). A role for inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome? Gut, 51(Suppl 1), i41–i44.

Camilleri, M., McKinzie, S., Busciglio, I., et al. (2008). Prospective study of motor, sensory, psychologic, and autonomic functions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 6, 772–781.

Salem, T. A., Molloy, R. G., & O’Dwyer, P. J. (2007). Prospective, five-year follow-up study of patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 50, 1460–1464.

Mayer, E. A., & Collins, S. M. (2002). Evolving pathophysiologic models of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology, 122, 2032–2048.

Dias, A., Samuel, R., Patel, V., et al. (2004). The impact associated with caring for a person with dementia: A report from the 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s Indian network. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19, 182–184.

Cohen, E., Fuller, G., Bolus, R., et al. (2013). Increased risk for irritable bowel syndrome after acute diverticulitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 11, 1614–1619.

Bolster, L. T., & Papagrigoriadis, S. (2003). Diverticular disease has an impact on quality of life—Results of a preliminary study. Colorectal Disease, 5, 320–323.

Comparato, G., Fanigliulo, L., Aragona, G., et al. (2007). Quality of life in uncomplicated symptomatic diverticular disease: Is it another good reason for treatment? Digestive Diseases, 25, 252–259.

Vu, M., Fuller, G., Bolus, R., et al. (2012, May). Post diverticulitis (DV) depression: Longitudinal analysis reveals higher incidence in cases vs. controls. Poster presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW), San Diego, CA.

Wong, W. D., Wexner, S. D., Lowry, A., et al. (2000). Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis—Supporting documentation. The Standards Task Force. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 43, 290–297.

Kohler, L., Sauerland, S., & Neugebauer, E. (1999). Diagnosis and treatment of diverticular disease: Results of a consensus development conference. The Scientific Committee of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery. Surgical Endoscopy, 13, 430–436.

Rafferty, J., Shellito, P., Hyman, N. H., et al. (2006). Practice parameters for sigmoid diverticulitis. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 49, 939–944.

Khanna, P., Agarwal, N., Khanna, D., et al. (2014). Development of an online library of patient-reported outcome measures in gastroenterology: The GI-PRO database. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 109, 234–248.

Reeve, B. B., Hays, R. D., Bjorner, J. B., et al. (2007). Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Medical Care, 45, S22–S31.

Cella, D., Yount, S., Rothrock, N., et al. (2007). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care, 45, S3–S11.

DeWalt, D. A., Rothrock, N., Yount, S., et al. (2007). Evaluation of item candidates: The PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care, 45, S12–S21.

Simpson, J., Scholefield, J. H., & Spiller, R. C. (2003). Origin of symptoms in diverticular disease. British Journal of Surgery, 90, 899–908.

Terwee, C. B., Jansma, E. P., Riphagen, I. I., et al. (2009). Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Quality of Life Research, 18, 1115–1123.

Greenhalgh, J. (2009). The applications of PROs in clinical practice: What are they, do they work, and why? Quality of Life Research, 18, 115–123.

Spiegel, B. M., Bolus, R., Han, S., et al. (2007). Development and validation of a disease-targeted quality of life instrument in chronic hepatitis B: The hepatitis B quality of life instrument, version 1.0. Hepatology, 46, 113–121.

Spiegel, B. M., Bolus, R., Agarwal, N., et al. (2010). Measuring symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome: Development of a framework for clinical trials. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 32, 1275–1291.

Ericsson, A. S. H. (1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data (2nd ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Willis, G. (1994). Cognitive interviewing and questionnaire design: A training manual. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Irwin, D. E., Varni, J. W., Yeatts, K., et al. (2009). Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: A patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7, 3.

Ware, J. E. & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30, 473–483.

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370.

Simpson, J., Neal, K. R., Scholefield, J. H., et al. (2003). Patterns of pain in diverticular disease and the influence of acute diverticulitis. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 15, 1005–1010.

Acknowledgments

The authors and Shire gratefully acknowledge the valued scientific contribution from Linnette Yen, who passed away in 2012.

Conflict of interest

Brennan Spiegel has received research support from Amgen Pharmaceuticals, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Shire Development LLC, and Theravance Pharmaceuticals. Gil Melmed has consulted for Abbvie, Jannsen, Given Imaging, Celgene, and Luitpold. He has received research support from Pfizer, and been on the speaker’s bureau for Abbott. Linnette Yen, deceased, was an employee of Shire and held stock/options in Shire. Paul Hodgkins and M. Haim Erder are Shire employees and own stock in the company. This study is supported by a research grant from Shire Development LLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclaimer The opinions and assertions contained herein are the sole views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Conceptual framework description

The conceptual framework in Fig. 1 posits four major concepts, discussed below.

Code counts from diverticular disease concept elicitation. The figure provides the absolute values for individual code counts. For example, there were nearly 70 instances of abdominal pain/discomfort (highest bar in histogram). In contrast, there were only two instances of diverticular disease impacting sleep. The bars are color-coded by major domains (physical symptom, cognitions and concerns, behaviors, and impact/consequences). (Color figure online)

Major Concept #1: Diverticular-related physical symptoms

Figure 2 in the manuscript presents the physical symptoms most commonly endorsed by patients in open-ended questioning. When asked to “list each of the most important symptoms that come to mind,” patients most commonly cited abdominal pain and discomfort, bloating, and flatulence.

Similar to work in IBS [36], patients with diverticular disease reported that abdominal pain can be multifaceted and that pain intensity, frequency, and predictability all impact HRQOL. Many patients believed that pain location is also important; some perceived that involvement of more regions beyond the typical left lower quadrant location led to worse HRQOL. Figure 3, below, shows a pain map of the specific regions patients identified as having self-reported diverticular-related pain—the distribution is focused in the infra-umbilical (43.8 %) and peri-umbilical (56.3 %) regions, less so the left lower quadrant (25 %). Patients used many descriptors for their chronic pain, including “pressure-like” (68 %), “aching” (62 %), “stabbing” (53 %), “sharp” (50 %), “cramping” (43 %), “burning” (25 %), and “spasm” (19 %). Eighty percent of patients reported ongoing pain between diverticulitis attacks, while others reported no pain between these episodes.

Patients described “bloating” in terms of how it looks versus how it feels. Patients described the look of bloating as “swollen,” “full of air,” “distended,” “looking fat,” and “rounded out.” Patients described the feeling of bloating as “a feeling of tightness,” “feeling pressure,” “feeling gassy,” and “heaviness.”

In addition to GI symptoms, patients endorsed a range of common extra-intestinal symptoms attributed to diverticular disease. The most frequently referenced symptoms were the presence of “fatigue,” “tiredness,” feeling “clammy” or “sweaty,” “faintness,” and “dizziness.”

Major Concept #2: Diverticulitis-related cognitions and concerns

Patients expressed a range of cognitions and concerns related to diverticular disease. Many believed their diverticulitis might flare up at any time (e.g., “Oh please not today”) or they had little control over their illness (“My life is falling apart because I have no control over this;” “I don’t know what to do about this”). Others believed there was something wrong inside their body (“I am busted inside;” “infected;” “poisoned;” “something strange is inside my guts;” “I’m dying internally”). Some discussed how diverticular disease has affected their self-perception (“I don’t like myself because of this;” “I am not a whole person anymore;” “I’m unusual;” “I’m diminished;” or “I think of myself according to all my stomach issues since having diverticulitis”). Others expressed concern about diverticular disease causing cancer or death (“Am I going to die from this?”; “this is scary;” “terrifying”). Other cognitions and concerns included diverticular-related embarrassment, confusion, and desire to seek information to better understand the disease.

Major Concept #3: Diverticular-related behavioral changes

Patients described restrictive and preventive behaviors related to diverticular disease. Dietary restrictions were most common (“I only eat salads now;” “I try to eat lots of fiber;” “I’ve become a vegetarian;” “I’m always conscious of what I eat and when I eat it;” “I avoid seeds and nuts”). Patients also described social restrictive behaviors (“I try to stay home more often;” “I don’t go out anymore;” “I just stay away from my friends now;” “No use going out to parties or going out to dinner;” “I’m isolated because of this”). Others discussed how diverticular disease undermines their physical activities (“I do not exercise as much anymore;” “I avoid abdominal exercises;” “I can’t lean over the pool table anymore when playing pool;” “I can’t even tie my shoes;” “I can’t pick up or lift things as easily anymore”) or even their clothing choices (“I have to wear looser clothes now”).

Major Concept #4: Diverticular-related emotional impact/consequences

Patients described physical, psychological, and social impacts and consequences of having diverticular disease. Some attributed the illness to interrupting their sleep (“It interferes with my sleep at night”), impacting sexual function (“I lost my sexual drive;” “Can’t have sex when I’m in pain”), and affecting work productivity (“I have to leave work early because of this”). Several believed that diverticular disease led to job dismissal (“I got fired because of how much it affected my work performance;” “My job was over once it started;” “I’ve lost jobs because of this;” “I can’t work anymore”). Patients described a range of psychological consequences of having diverticular disease, including anger (“It gives me a sense of frustration;” “I’m pissed about this”), depression (“It disturbs me mentally;” “This is ruining my life;” “This feels kind of bleak to me”), devitalization and lack of concentration (“It affects my motivation;” “It makes me feel lazy;” “I lose my concentration thinking about it”), and anxiety.

Appendix 2: DV-QOL v1.0

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spiegel, B.M.R., Reid, M.W., Bolus, R. et al. Development and validation of a disease-targeted quality of life instrument for chronic diverticular disease: the DV-QOL. Qual Life Res 24, 163–179 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0753-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0753-1