Abstract

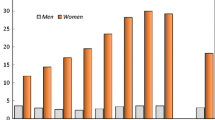

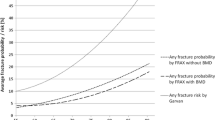

The incidence of fragility fractures begins to increase in middle age. We investigated prospectively risk factors for low-energy fractures in men and women, and specifically for forearm, proximal humerus, vertebral, and ankle fractures. The population-based Malmö Preventive Project consists of 22,444 men and 10,902 women, mean age 44 and 50 years, respectively, at inclusion. Baseline assessment included multiple examinations and lifestyle information. Mean follow-up was 19 and 15 years for men and women, respectively, regarding incident fractures. Fractures were ascertained from radiographic files. At least one low-energy fracture occurred in 1,262 men and 1,257 women. In men, the risk factors most strongly associated with low-energy fractures were diabetes [relative risk (RR) 2.38, confidence interval (CI) 95% 1.65–3.42] and hospitalization for mental health problems (RR 1.92, CI 95% 1.47–2.51). Factors associated with mental health and lifestyle significantly increased the fracture risk in most of the specific fracture groups: hospitalizations for mental health problems (RR 2.28–3.38), poor appetite (RR 3.05–3.43), sleep disturbances (RR 1.72–2.95), poor self-rated health (RR 1.80–1.83), and smoking (RR 1.70–2.72). In women, the risk factors most strongly associated with low-energy fractures were diabetes (RR 1.87, CI 95% 1.26–2.79) and previous fracture (RR 2.00, CI 95% 1.56–2.58). High body mass index (BMI) significantly increased the risk of proximal humerus and ankle fractures (RR 1.21–1.33) while, by contrast, lowering the risk of forearm fractures (RR 0.88, CI 95% 0.81–0.96). Risk factors for fracture in middle-aged men and women are similar but with gender differences for forearm, vertebral, proximal humerus, and hip fracture whereas risk factors for ankle fractures differ to a certain extent. The risk-factor pattern indicates a generally impaired health status, with mental health problems as a major contributor to fracture risk, particularly in men.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Obrant KJ et al (1989) Increasing age-adjusted risk of fragility fractures: a sign of increasing osteoporosis in successive generations? Calcif Tissue Int 44(3):157–167

Kannus P et al (2002) Why is the age-standardized incidence of low-trauma fractures rising in many elderly populations? J Bone Miner Res 17(8):1363–1367

van Staa TP et al (2001) Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 29(6):517–522

Kanis JA, Pitt FA (1992) Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Bone 13(Suppl 1):S7–S15

Melton LJ 3rd et al (2003) Cost-equivalence of different osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 14(5):383–388

Ettinger B et al (2003) Limb fractures in elderly men as indicators of subsequent fracture risk. Arch Intern Med 163(22):2741–2747

Klotzbuecher CM et al (2000) Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res 15(4):721–739

Johnell O et al (2004) Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 15(3):175–179

Berglund G et al (1996) Cardiovascular risk groups and mortality in an urban Swedish male population: the Malmo Preventive Project. J Intern Med 239(6):489–497

Holmberg A et al (2004) Forearm bone mineral density in 1294 middle-aged women: a strong predictor of fragility fractures. J Clin Densitom 7(4):419–423

Holmberg AH et al (2005) Risk factors for hip fractures in a middle-aged population: a study of 33,000 men and women. Osteoporos Int 16(12):2185–2194

Jonsson B et al (1993) Life-style and different fracture prevalence: a cross-sectional comparative population-based study. Calcif Tissue Int 52(6):425–433

Sanders KM et al (1999) Age- and gender-specific rate of fractures in Australia: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 10(3):240–247

Kanis JA et al (2000) Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmo. Osteoporos Int 11(8):669–674

Melton LJ 3rd et al (1998) Long-term trends in the incidence of distal forearm fractures. Osteoporos Int 8(4):341–348

Chu SP et al (2004) Risk factors for proximal humerus fracture. Am J Epidemiol 160(4):360–367

Nguyen TV et al (2001) Risk factors for proximal humerus, forearm, and wrist fractures in elderly men and women: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study. Am J Epidemiol 153(6):587–595

Olsson C, Nordqvist A, Petersson CJ (2004) Increased fragility in patients with fracture of the proximal humerus: a case control study. Bone 34(6):1072–1077

Guggenbuhl P, Meadeb J, Chales G (2005) Osteoporotic fractures of the proximal humerus, pelvis, and ankle: epidemiology and diagnosis. Jt Bone Spine 72(5):372–375

Honkanen R et al (1998) Relationships between risk factors and fractures differ by type of fracture: a population-based study of 12,192 perimenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 8(1):25–31

Valtola A et al (2002) Lifestyle and other factors predict ankle fractures in perimenopausal women: a population-based prospective cohort study. Bone 30(1):238–242

Seeley DG et al (1996) Predictors of ankle and foot fractures in older women. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res 11(9):1347–1355

Ahmed LA et al (2005) Diabetes mellitus and the risk of non-vertebral fractures: the Tromso study. Osteoporos Int :1–6

Forsen L et al (1999) Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of hip fracture: results from the Nord-Trondelag Health Survey. Diabetologia 42(8):920–925

Ottenbacher KJ et al (2002) Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for hip fracture in Mexican American older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 57(10):M648–M653

Schwartz AV et al (2001) Older women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86(1):32–38

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2005) Relative fracture risk in patients with diabetes mellitus, and the impact of insulin and oral antidiabetic medication on relative fracture risk. Diabetologia 48(7):1292–1299

Adami S et al (2004) Relationship between lipids and bone mass in 2 cohorts of healthy women and men. Calcif Tissue Int 74(2):136–142

Lidfeldt J et al (2002) The influence of hormonal status and features of the metabolic syndrome on bone density: a population-based study of Swedish women aged 50 to 59 years. The women’s health in the Lund area study. Metabolism 51(2):267–270

Conigrave KM et al (2003) Traditional markers of excessive alcohol use. Addiction 98(Suppl 2):31–43

Conigrave KM, Saunders JB, Whitfield JB (1995) Diagnostic tests for alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol 30(1):13–26

Banciu T et al (1983) Serum gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase assay in the detection of alcohol consumers and in the early and stadial diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease. Med Interne 21(1):23–29

Trell E, Kristenson H, Fex G (1984) Alcohol-related problems in middle-aged men with elevated serum gamma-glutamyltransferase: a preventive medical investigation. J Stud Alcohol 45(4):302–309

Yokoyama H et al (2003) Association between gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase activity and status of disorders constituting insulin resistance syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27(8 Suppl):22S–25S

Kanis J et al (1999) Risk factors for hip fracture in men from southern Europe: the MEDOS study. Mediterranean Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 9(1):45–54

Johnell O et al (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in European women: the MEDOS Study. Mediterranean Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 10(11):1802–1815

Clark MK et al (2003) Bone mineral density and fractures among alcohol-dependent women in treatment and in recovery. Osteoporos Int 14(5):396–403

Kanis JA, Johnell O (2005) Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos Int 16(3):229–238

Law MR, Hackshaw AK (1997) A meta-analysis of cigarette smoking, bone mineral density and risk of hip fracture: recognition of a major effect. BMJ 315(7112):841–846

Huopio J et al (2000) Risk factors for perimenopausal fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 11(3):219–227

Kiel DP et al (1996) The effect of smoking at different life stages on bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Osteoporos Int 6(3):240–248

Gerdhem P, Obrant KJ (2002) Effects of cigarette-smoking on bone mass as assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and ultrasound. Osteoporos Int 13(12):932–936

Ahmed LA et al (2006) Self-reported diseases and the risk of non-vertebral fractures: the Tromso study. Osteoporos Int 17(1):46–53

Acknowledgements

The Swedish Research Council Project K2003-73X-11610-08A, The Kock Foundation, The Herman Järnhardt Foundation, Malmö University Hospital Funds, and regional research grants supported this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0164-4

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holmberg, A.H., Johnell, O., Nilsson, P.M. et al. Risk factors for fragility fracture in middle age. A prospective population-based study of 33,000 men and women. Osteoporos Int 17, 1065–1077 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0137-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0137-7