Abstract

Purpose

The administration of chloride-rich intravenous (IV) fluid and hyperchloraemia have been associated with perioperative renal injury. The aim of this study was to determine whether a comprehensive perioperative protocol for the administration of chloride-limited IV fluid would reduce perioperative renal injury in adults undergoing cardiac surgery.

Methods

From February 2014 through to December 2015, all adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery within a single academic medical center received IV fluid according to the study protocol. The perioperative protocol governed all fluid administration from commencement of anesthesia through to discharge from the intensive care unit and varied over four sequential periods, each lasting 5 months. In periods 1 and 4 a chloride-rich strategy, consisting of 0.9% saline and 4% albumin, was adopted; in periods 2 and 3, a chloride-limited strategy, consisting of a buffered salt solution and 20% albumin, was used. Co-primary outcomes were peak delta serum creatinine (∆SCr) within 5 days after the operation and KDIGO-defined stage 2 or stage 3 acute kidney injury (AKI) within 5 days after the operation.

Results

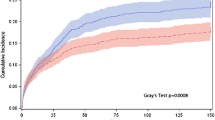

We enrolled and analysed data from 1136 patients, with 569 patients assigned to a chloride-rich fluid strategy and 567 to a chloride-limited one. Compared with a chloride-limited strategy and adjusted for prespecified covariates, there was no association between a chloride-rich perioperative fluid strategy and either peak ∆S Cr, transformed to satisfy the assumptions of multivariable linear regression [regression coefficient 0.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.03 to 0.08); p = 0.39], or stage 2 or 3 AKI (adjusted odds ratio 0.97, 95% CI 0.65–1.47; p = 0.90].

Conclusions

A perioperative fluid strategy to restrict IV chloride administration was not associated with an altered incidence of AKI or other metrics of renal injury in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02020538.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dasta JF, Kane-Gill SL, Durtschi AJ, Pathak DS, Kellum JA (2008) Costs and outcomes of acute kidney injury (AKI) following cardiac surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23:1970–1974

Ricci Z, Cruz D, Ronco C (2007) The RIFLE criteria and mortality in acute kidney injury: a systematic review. Kidney Int 73:538–546

Robert AM, Kramer RS, Dacey LJ et al (2010) Cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a comparison of two consensus criteria. Ann Thorac Surg 90:1939–1943

Xu JR, Zhu JM, Jiang J et al (2015) Risk factors for long-term mortality and progressive chronic kidney disease associated with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Med (Baltimore) 94:e2025

Parke RL, McGuinness SP, Gilder E, McCarthy LW, Cowdrey KA (2015) A randomised feasibility study to assess a novel strategy to rationalise fluid in patients after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 115:45–52

Scheingraber S, Rehm M, Sehmisch C, Finsterer U (1999) Rapid saline infusion produces hyperchloremic acidosis in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Anesthesiology 90:1265–1270

Wilkes NJ, Woolf R, Mutch M et al (2001) The effects of balanced versus saline-based hetastarch and crystalloid solutions on acid-base and electrolyte status and gastric mucosal perfusion in elderly surgical patients. Anesth Analg 93:811–816

Chowdhury AH, Cox EF, Francis ST, Lobo DN (2012) A randomized, controlled, double-blind crossover study on the effects of 2-L infusions of 0.9% saline and plasma-lyte(R) 148 on renal blood flow velocity and renal cortical tissue perfusion in healthy volunteers. Ann Surg 256:18–24

Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Story D, Kellum J (2010) Bench-to-bedside review: chloride in critical illness. Crit Care 14:226

McCluskey SA, Karkouti K, Wijeysundera D, Minkovich L, Tait G, Beattie WS (2013) Hyperchloremia after noncardiac surgery is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality: a propensity-matched cohort study. Anesth Analg 117:412–421

Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Hegarty C, Story D, Ho L, Bailey M (2012) Association between a chloride-liberal vs chloride-restrictive intravenous fluid administration strategy and kidney injury in critically ill adults. JAMA 308:1566–1572

Young P, Bailey M, Beasley R et al (2015) Effect of a buffered crystalloid solution vs saline on acute kidney injury among patients in the intensive care unit: the SPLIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314:1701–1710

Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group (2012) KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2:1–138

Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P et al (1999) Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 15:816–822

Thakar CV, Arrigain S, Worley S, Yared J-P, Paganini EP (2005) A clinical score to predict acute renal failure after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:162–168

Yunos NM, Kim IB, Bellomo R et al (2011) The biochemical effects of restricting chloride-rich fluids in intensive care. Crit Care Med 39:2419–2424

Nichol A, Bailey M, Egi M et al (2011) Dynamic lactate indices as predictors of outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care 15:R242

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ et al (2008) Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 337:a2390

Nadeem A, Salahuddin N, El Hazmi A et al (2014) Chloride-liberal fluids are associated with acute kidney injury after liver transplantation. Crit Care 18:625

Shaw AD, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL et al (2012) Major complications, mortality, and resource utilization after open abdominal surgery: 0.9% saline compared to Plasma-Lyte. Ann Surg 255:821–829

Shaw AD, Raghunathan K, Peyerl FW, Munson SH, Paluszkiewicz SM, Schermer CR (2014) Association between intravenous chloride load during resuscitation and in-hospital mortality among patients with SIRS. Intensive Care Med 40:1897–1905

Zhang Z, Xu X, Fan H, Li D, Deng H (2013) Higher serum chloride concentrations are associated with acute kidney injury in unselected critically ill patients. BMC Nephrol 14:235

Raghunathan K, Shaw A, Nathanson B et al (2014) Association between the choice of IV crystalloid and in-hospital mortality among critically ill adults with sepsis. Crit Care Med 42:1585–1591

Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Glassford N, Sutcliffe H, Lam Q, Bailey M (2015) Chloride-liberal vs. chloride-restrictive intravenous fluid administration and acute kidney injury: an extended analysis. Intensive Care Med 41:257–264

Burdett E, Dushianthan A, Bennett-Guerrero E et al (2012) Perioperative buffered versus non-buffered fluid administration for surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:4089

Sen A, Keener CM, Sileanu FE et al (2017) Chloride content of fluids used for large-volume resuscitation is associated with reduced survival. Crit Care Med 45:e146–e153

McIlroy DR, Farkas D, Argenziano M, Umann T, Sladen R (2013) Incorporating oliguria into the diagnostic criteria for acute kidney injury after on-pump cardiac surgery: impact on incidence and outcomes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 27:1145–1152

Semler MW, Wanderer JP, Ehrenfeld JM et al (2016) Balanced crystalloids versus saline in the intensive care unit: the SALT randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. doi:10.1164/rccm.201607-1345OC

Acknowledgements

D. McIlroy and J. Kasza had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The statistical analysis was jointly conducted by J. Kasza (biostatistician) and D. McIlroy. The study was jointly funded by grants from the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists/International Anesthesia Research Society. Neither of the funding bodies had any input into the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

All of the authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest related to the submitted manuscript.

Additional information

Take-home message:

In a pragmatic trial in adults undergoing cardiac surgery, limiting the chloride content of perioperative IV fluid did not reduce AKI.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McIlroy, D., Murphy, D., Kasza, J. et al. Effects of restricting perioperative use of intravenous chloride on kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: the LICRA pragmatic controlled clinical trial. Intensive Care Med 43, 795–806 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4772-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4772-6