Abstract

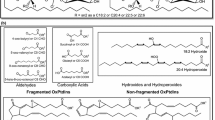

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading causes of mortality and morbidity among elderly in westernized societies (1). The main causes for the clinical complications associated with cardiovascular diseases are atherosclerotic plaque formation and thrombosis (2). The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is complex and multi factorial but one of the most important risk factors linked to coronary artery disease is increased levels of the plasma ApoB-100 containing lipoproteins low density lipoproteins (LDL) and very low density lipoproteins (VLDL). The atherosclerotic lesion is characterized by a focal accumulation of ApoB-100 lipoproteins, extracellular matrix, and cells in the arterial intima, accompanied by an inflammatory reaction (3,4). In vivo and in vitro data support the hypothesis that sulfated extracellular proteoglycans (PG) may be responsible for the selective retention of LDL in the arterial wall (5,6). These interactions facilitate further modifications of LDL such as oxidation, proteolysis, and lipolysis, which alter physicochemical properties of the lipoproteins and may contribute to atherogenesis (3). Studies from our laboratory and from others have consistently demonstrated the presence of abundant group IIA secretory non-pancreatic phospholipase A2 (snpPLA2) in human atherosclerotic lesions (7-10). In addition, snpPLA2 can also be detected in the circulation, and hyperphospholipasemia is usually closely associated to pathological conditions that include a systemic inflammatory response (11). Recently, it was demonstrated that circulating levels of snpPLA2 were associated with an increased risk for coronary artery disease in humans and predicted disease progression in this group of patients (12). The physiological function(s) of snpPLA2 is still not clear, but it has been suggested to play an important role as a mediator of inflammation (13). The lipolytic action of snpPLA2 generates non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) and lyso-phospholipids from phosphoglyceride-aggregates. Lipoproteins appear to be physiological substrates for snpPLA2 in vivo (14). An LDL particle consists of a neutral lipid core made mainly of triglycerides and cholesteryl esters surrounded by amphipatic phospholipids and unesterified cholesterol with an embedded ApoB-100 molecule. SnpPLA2 may be proatherogenic by two mechanisms (15). First, by generating NEFA and lyso-phospholipids at sites of lipoprotein retention in the arterial wall. These products may directly affect the functionality of the surrounding cells and serve as precursors for the production of proinflammatory factors such as eicosanoids, platelet-activating factor, and lysophosphatidic acid. If locally released in the arterial intima these reactive components may induce and sustain an inflammatory response. Second, modification of lipoproteins by snpPLA2 in the circulation or focally in the arterial wall may lead to alterations of the lipoprotein properties and generation of lipoprotein particles with increased atherogenicity.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Preview

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

WHO. World Health Report. Report of the Director General. WHO, Geneva. 1997.

Falk E. Stable versus unstable atherosclerosis: clinical aspects. Am Heart J 1999;138(5 Pt 2):S421–5.

Williams KJ, Tabas I. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1995;15(5):551–61.

Ross R. Atherosclerosis - An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:115–126.

Hurt-Camejo E, Olsson U, Wiklund O, Bondjers G, Camejo G. Cellular consequences of the association of apoB lipoproteins with proteoglycans. Potential contribution to atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997;17(6):1011–7.

Camejo G, Hurt-Camejo E, Wiklund O, Bondjers G. Association of apo B lipoproteins with arterial proteoglycans: pathological significance and molecular basis. Atherosclerosis 1998;139(2):205–22.

Elinder LS, Dumitrescu A, Larsson P, Hedin U, Frostegard J, Claesson HE. Expression of phospholipase A2 isoforms in human normal and atherosclerotic arterial wall. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997;17(10):2257–63.

Hurt-Camejo E, Andersen S, Standal R, et al. Localization of nonpancreatic secretory phospholipase A2 in normal and atherosclerotic arteries. Activity of the isolated enzyme on low-density lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997;17(2):300–9.

Romano M, Romano E, Bjorkerud S, Hurt-Camejo E. Ultrastructural localization of secretory type 11 phospholipase A2 in atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic regions of human arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998;18(4):519–25.

Schiering A, Menschikowski M, Mueller E, Jaross W. Analysis of secretory group II phospholipase A2 expression in human aortic tissue in dependence on the degree of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 1999;144(1):73–8.

Nevalainen TJ, Grönroos JM. Serum Phospholipase A2 in Inflammatory Diseases. In: Uhl W, Nevalainen TJ, Buehler MW, eds. Phospholipase A2. Basic and Clinical Aspects in Inflammatory Diseases. Basel: Karger, 1997:104–109. vol 24).

Kugiyama K, Ota Y, Takazoe K, et al. Circulating levels of secretory type II phospholipase A(2) predict coronary events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 1999;100(12):1280–4.

Dennis EA. The growing phospholipase A2 superfamily of signal transduction enzymes. Trends Biochem Sci 1997;22(1):1–2.

Pruzanski W, Stefanski E, de Beer FC, et al. Lipoproteins are substrates for human secretory group IIA phospholipase A2: preferential hydrolysis of acute phase HDL. 1998.

Hurt-Camejo E, Camejo G. Potential involvement of type II phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 1997;132(1):1–8.

Sartipy P, Camejo G, Svensson L, Hurt-Camejo E. Phospholipase A(2) modification of low density lipoproteins forms small high density particles with increased affinity for proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans. J Biol Chem 1999;274(36):25913–20.

Aggerbeck LP, Kezdy FJ, Scanu AM. Enzymatic probes of lipoprotein structure. Hydrolysis of human serum low density lipoprotein-2 by phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem 1976;251(12):3823–30.

Chapman MJ, Guerin M, Bruckert E. Atherogenic, dense low-density lipoproteins. Pathophysiology and new therapeutic approaches. Eur Heart J 1998;19 Suppl A:A24–30.

Austin MA, King MC, Vranizan KM, Krauss RM. Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype. A proposed genetic marker for coronary heart disease risk. Circulation 1990;82(2):495–506.

Capell WH, Zambon A, Austin MA, Brunzell JD, Hokanson JE. Compositional differences of LDL particles in normal subjects with LDL subclass phenotype A and LDL subclass phenotype B. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996;16(8):1040–6.

Hurt-Camejo E, Camejo G, Rosengren B, Lopez F, Wiklund O, Bondjers G. Differential uptake of proteoglycan-selected subfractions of low density lipoprotein by human macrophages. J Lipid Res l990;31(8):1387–98.

Nordestgaard BG, Wootton R, Lewis B. Selective retention of VLDL, IDL, and LDL in the arterial intima of genetically hyperlipidemic rabbits in vivo. Molecular size as a determinant of fractional loss from the intima-inner media. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1995;I5(4):534–42.

Bjornheden T, Babyi A, Bondjers G, Wiklund O. Accumulation of lipoprotein fractions and subfractions in the arterial wall, determined in an in vitro perfusion system. Atherosclerosis 1996;123(l-2):43–56.

Tribble DL, Krauss RM, Lansberg MG, Thiel PM, van den Berg JJ. Greater oxidative susceptibility of the surface monolayer in small dense LDL may contribute to differences in copper-induced oxidation among LDL density subfractions. J Lipid Res 1995;36(4):662–71.

Olsson U, Camejo G, Hurt-Camejo E, Elfsber K, Wiklund O, Bondjers G. Possible functional interactions of apolipoprotein B-100 segments that associate with cell proteoglycans and the ApoB/E receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997;17(1):149–55.

Kleinman Y, Krul ES, Burnes M, Aronson W, Pfleger B, Schonfeld G. Lipolysis of LDL with phospholipase A2 alters the expression of selected apoB-100 epitopes and the interaction of LDL with cells. J Lipid Res 1988;29(6):729–43.

Lund-Katz S, Laplaud PM, Phillips MC, Chapman MJ. Apolipoprotein B-100 conformation and particle surface charge in human LDL subspecies: implication for LDL receptor interaction. Biochemistry 1998;37(37):12867–74.

Neuzil J, Upston JM, Witting PK, Scott KF, Stocker R. Secretory phospholipase A2 and lipoprotein lipase enhance 15- lipoxygenase-induced enzymic and nonenzymic lipid peroxidation in low-density lipoproteins. Biochemistry 1998;37(25):9203–10.

Schissel SL, Jiang X, Tweedie-Hardman J, et al. Secretory sphingomyelinase, a product of the acid sphingomyelinase gene, can hydrolyze atherogenic lipoproteins at neutral pH. Implications for atherosclerotic lesion development. J Biol Chem 1998;273(5):2738–46.

Marathe S, Kuriakose G, Williams KJ, Tabas I. Sphingomyelinase, an enzyme implicated in atherogenesis, is present in atherosclerotic lesions and binds to specific components of the subendothelial extracellular matrix. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19(11):2648–58.

Hoover-Plow J, Khaitan A, Fless GM. Phospholipase A2 modification enhances lipoprotein(a) binding to the subendothelial matrix. Thromb Haemost l998;79(3):640–8.

Aviram M, Maor I. Phospholipase A2-modified LDL is taken up at enhanced rate by macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992;185(l):465–72.

Menschikowski M, Lattke P, Bergmann S, Jaross W. Exposure of macrophages to PLA2-modified lipoproteins leads to cellular lipid accumulations. Anal Cell Pathol 1995;9(2):113–21.

Ivandic B, Castellani LW, Wang XP, et al. Role of group II secretory phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis: 1. Increased atherogenesis and altered lipoproteins in transgenic mice expressing group Ila phospholipase A2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19(5):1284–90.

Leitinger N, Watson AD, Hama SY, et al. Role of group II secretory phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis: 2. Potential involvement of biologically active oxidized phospholipids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19(5):1291–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2002 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sartipy, P., Camejo, G., Svensson, L., Hurt-Camejo, E. (2002). Phospholipase A2 Modification of Lipoproteins: Potential Effects on Atherogenesis. In: Honn, K.V., Marnett, L.J., Nigam, S., Dennis, E., Serhan, C. (eds) Eicosanoids and Other Bioactive Lipids in Cancer, Inflammation, and Radiation Injury, 5. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 507. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0193-0_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0193-0_1

Publisher Name: Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN: 978-1-4613-4960-0

Online ISBN: 978-1-4615-0193-0

eBook Packages: Springer Book Archive