Abstract

Background:

Influenza causes a substantial socioeconomic burden. In Belgium, only 54% of the target group receives an annual vaccination. Patient reminder/recall systems are effective in improving vaccination rates in primary care, but little is known about patients' preferences on notification of influenza vaccination.

Aims:

To evaluate whether general practice patients wish to be notified of the possibility of receiving influenza immunisation, and how.

Methods:

In January 2008, 750 questionnaires were handed out to all consecutive patients aged >18 years in three Belgian general practices. Main outcome measures were the percentage wanting to be notified, demographic and medical factors influencing the information needs of the patients and the specific way in which patients wanted to be notified.

Results:

About 80% of respondents wanted to be notified of the possibility of influenza vaccination. Logistic regression analysis showed that those who had previously been vaccinated particularly wished to be notified, both in the total population (OR 4.45; 95% CI 2.87 to 6.90; p<0.0001) and in the subgroup of high-risk individuals (OR 9.05; 95% CI 4.47 to 18.33; p<0.0001). More than 85% of the participants wanted to be informed by their family physician, mostly during a consultation regardless of the reason for the encounter. The second most preferred option was a letter sent by the family physician enclosing a prescription.

Conclusions:

The majority of general practice patients want to be notified of the possibility of influenza vaccination. More than 85% of participants who wanted to be notified preferred to receive this information from their family physician, mostly by personal communication during a regular visit. However, since a large minority preferred to be addressed more proactively (letter, telephone call, e-mail), GPs should be encouraged to combine an opportunistic approach with a proactive one.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenza is a highly infectious acute respiratory illness. Worldwide, 20% of children and 5% of adults develop symptomatic influenza each year.1 Influenza causes acute respiratory symptoms combined with fever and myalgia. The clinical features typically last for 3–5 days, although the cough, tiredness and malaise may last for 1–2 weeks. Influenza outbreaks occur annually across the world, causing increased morbidity and hospitalisation rates and excess mortality. Elderly people and high-risk patients with concomitant chronic diseases are most susceptible to complications of influenza, causing a substantial socioeconomic burden for society.1,2 Pregnant women and their newborn infants are also at increased risk of developing serious complications.3

Influenza-related clinical complications are predominantly respiratory, such as acute bronchitis, bacterial or viral pneumonia, and exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Non-respiratory complications such as febrile convulsions (in children), heart failure, myositis, encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome and toxic shock syndrome occur less frequently.4

Seasonal influenza vaccination has been proved to be effective and safe. In adults, the efficacy of the vaccine in preventing influenza is estimated at 77%. Vaccination of patients with chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease and diabetes reduces hospital admissions, complications and mortality.1 In pregnant women, maternal influenza immunisation has a substantial protective effect in both mothers and their young infants up to 6 months of age.5

The most common adverse effects of vaccination are soreness at the immunisation site, fever, malaise and myalgia. Immediate allergic reactions are very rare but anaphylaxis can occur after administration of a vaccine, most frequently caused by hypersensitivity to residual egg protein.1

In Belgium, a list of high-risk groups eligible for influenza vaccination is issued yearly by the Superior Health Council, the scientific advisory body of the Belgian Federal Public Service of Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment (Box 1).6

In Belgium, only 54% of the population eligible for immunisation currently receive an annual influenza vaccine.7 Using a computer-supported strategy, the general practitioner (GP) can attain a vaccination coverage of 70%.8

Patient reminder/recall systems have proved to be effective in improving vaccination rates in primary care settings. All types of patient reminders are effective (e.g. postcards, letters, telephone calls), with telephone reminders being the most effective but most costly.9 To increase influenza vaccination rates in those aged 60 years and older in the community, personalised postcards or telephone calls are effective, and home visits and facilitators may be effective.10 The use of multiple reminders also appears to be more effective than single reminders.11 Provider reminder systems that inform vaccine providers that the individual clients are due for vaccination are also effective in improving targeted vaccination coverage among the elderly12 and high-risk adults.13

The Flemish Agency for Care and Health develops and implements the health policy of the Flemish community in Belgium. This includes the organisation of a yearly influenza vaccination campaign executed by the ‘Vlaams Griepplatform’. This task force includes representatives of family physicians, pharmacists, health insurance companies, the Diabetes Association and associations for the elderly. Influenza immunisation is promoted by providing flyers and posters for public places, family physicians and pharmacists. They also advertise in papers and magazines and organise press conferences. In parallel, ‘Domus Medica’, the scientific organisation of Flemish family physicians, issues guidelines for good medical practice. They advise family physicians to follow a staged approach in promoting influenza vaccination among high-risk patients by (1) offering the influenza vaccine opportunistically; (2) sending out invitations; and (3) telephoning non-responders.

However, little is known about patients' preferences on notification about influenza vaccination.

This study aims to evaluate whether family practice patients wish to be notified of the possibility of receiving an influenza immunisation. In addition, the influence of age, gender, language group (Dutch/French), presence of risk factors, number of risk factors and influenza vaccination history on whether or not people wanted to be notified was evaluated. Finally, the specific manner in which the participants preferred to be notified was assessed.

Methods

In January 2008 a questionnaire was handed out by GPs to 750 consecutive patients aged >18 years in three Belgian family practices (250 patients in each participating practice). The participating practices were demographically spread (metropolitan, urban and rural environment). None had a prior vaccination policy and vaccination had been previously offered in an opportunistic manner.

The questionnaire contained questions about demographic characteristics, medical indications for influenza vaccination, and opinions on how people preferred to be notified of the possibility of influenza immunisation. Since, to the best of our knowledge, there are no existing validated questionnaires which address the preferred manner of notifying patients about influenza vaccination, the questionnaire was self-developed (see Appendix 1, available online at www.thepcrj.org). Age, gender, language group (Dutch/French), the presence of risk factors, number of risk factors and influenza vaccination history were examined for their influence on patients' information needs using both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Analyses were performed on the total study population and on the high-risk population.

Data were analysed with the Statistical Package for Social Science version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Of a total of 750 questionnaires, 132 (18%) were excluded because they were incomplete. A total of 618 forms were analysed. The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The median age was 50 years and 59% were women. Of the 618 participants included in the study, 290 (47%) had one or more reasons to be eligible for immunisation (target group). Participants who had previously received at least one influenza vaccination represented 57% and 75% of the total population and the target group, respectively.

Need for notification of the possibility of influenza immunisation

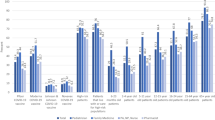

Table 2 shows that, overall, about 80% of the total population wanted to be notified of the possibility of influenza vaccination. The need for notification was highest in the previously vaccinated group and in the target group (90% and 84%, respectively). However, it was significantly lower in the group of subjects who had never been vaccinated before, both in the total study population (66%, p<0.0001) and in the target group (57%, p<0.0001).

Table 3 shows the results of the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, with ‘wanting to be informed’ as the dependent variable. The univariate analysis shows that patients were more likely to request notification if they were older, male, had been vaccinated before and had more risk factors. In the multivariate analysis, ‘previously vaccinated’ remained an independent predictor for the wish to be notified about influenza vaccination, both in the total population (OR 4.45; 95% CI 2.87 to 6.90; p<0.0001) and in the subgroup of the target group (OR 9.05; 95% CI 4.47 to 18.33; p<0.0001). In the target group, men wanted to be notified more than women (OR 3.07; 95% CI 1.30 to 7.23; p=0.01).

Preferred method of being notified

Table 4 shows the specific way in which the participants preferred to be notified of the possibility of influenza vaccination. More than 85% of the total population wanted to be notified by their family physician, mostly during a regular consultation regardless of the reason for the encounter. The second most preferred option was a letter sent by the family physician enclosing a prescription for the influenza vaccine. Similar results were found in the target group.

Discussion

Main findings and interpretation in relation to previously published work

This study shows that about 80% of family practice patients wanted to be notified of the possibility of receiving an influenza vaccine. However, the wish to be notified was strongest in patients who had previously been vaccinated at least once (90%). Subjects who had never been vaccinated expressed less need for notification (p<0.0001) in both the total population (66%) and in the target group (57%). Even though the present study did not ask about the reasons for refusal of notification, a possible explanation for this finding may be that previously vaccinated patients are already convinced of the usefulness of the vaccine whereas some people have already made up their mind about their refusal to be vaccinated and do not want to be asked again. A subgroup analysis of patients who had never been vaccinated within the target group showed that older people in particular did not want further notification (data not shown). It may be difficult to convince these patients in the future of the benefits of immunisation. A study in the USA in people aged 65 years and older showed that the most frequently self-reported reasons for not receiving an influenza vaccine were not knowing that the vaccine was needed and concerns that the vaccination might cause influenza or side effects.14

A rather surprising finding was that, in the target group, men wanted to be notified about influenza vaccination more than women. We found no significant differences in vaccination history and risk factors between sexes that could explain this finding.

More than 85% of the participants who wanted to be notified expressed their wish to receive information on influenza vaccination from their family physician, mostly by a personal communication during a regular visit. An enquiry on influenza immunisation by the OCL (Ondersteuningcel Logo's, an organisation engaged in preventive health care in Belgium) showed that family physicians initiated the vaccination in 72% of cases.15 In the same study, 59% of those who had never been vaccinated stated that their family physician could persuade them to be immunised. Advice concerning influenza vaccination given by the doctor is one of the most important predictive factors for vaccination in elderly patients and those at risk.16 Our study results confirm the determining role of the family physician in influenza vaccination.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strength of this study is that, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate patients' opinions on notification of the possibility of influenza vaccination. However, there are some weaknesses. Because of practical considerations, patients visited at home were not included in the study. We acknowledge that the broad inclusion criteria of this study may have led to the inclusion of subjects never really intended for vaccination, who were therefore answering hypothetical questions. However, certain conditions making subjects eligible for vaccination can be present at a young age (e.g. pregnancy, healthcare personnel, early-onset diabetes). Moreover, the presence of indications for influenza vaccination can change with time, and subjects who are not presently eligible for vaccination can become so in the future. In addition, patients' risk factors and vaccination history were self-declared. Finally, it should be emphasised that this survey was held in a group of family practice patients, which may have influenced their choice for the family physician as their main potential informer. However, notifying patients in their preferred way may lead to an increase in vaccination coverage.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

A larger population-based study could put a new perspective on this issue.

Our findings have some implications for clinical practice. Although the most preferred manner of notification was a personal communication by the GP during a visit (an opportunistic approach), a large minority preferred to be addressed more proactively (by a letter sent by the GP with or without an enclosed prescription, e-mail or telephone call). GPs should be encouraged to combine an opportunistic approach with a proactive one.

Our data did not reveal differences in the way people wanted to be notified according to their vaccination history or their eligibility for vaccination. There is therefore no need for different information strategies in the different subgroups analysed.

Conclusions

This study showed that most family practice patients want to be notified of the possibility of influenza vaccination, especially if they have previously been vaccinated. Notifying patients in their preferred way may lead to an increase in vaccination coverage. More than 85% of the participants preferred to receive the information from their family physician, mostly by a personal communication during a regular visit. Since a large minority preferred to be addressed more proactively (by letter, telephone call or e-mail), GPs should be encouraged to combine an opportunistic approach with a proactive one.

References

Nicholson KG, Wood JM, Zambon M . Influenza. Lancet 2003;362(9397):1733–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14854-4

Meier CR, Napalkov PN, Wegmuller Y, Jefferson T, Jick H . Population-based study on incidence, risk factors, clinical complications and drug utilisation associated with influenza in the United Kingdom. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000;19(11):834–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s100960000376

Tamma PD, Ault KA, del RC, Steinhoff MC, Halsey NA, Omer SB . Safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201(6):547–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.034

Turner D, Wailoo A, Nicholson K, Cooper N, Sutton A, Abrams K . Systematic review and economic decision modelling for the prevention and treatment of influenza A and B. Health Technol Assess 2003;7(35):1–170.

Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med 2008;359(15):1555–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0708630

Federale Overheidsdienst Volksgezondheid: Hoge gezondheidsraad. Adviezen en Brochures van de HGR: Vaccinatie tegen seizoensgebonden griep winterseizoen 2007–2008 [Superior Health Council. Advises and Brochures of the SHC: Vaccination against seasonal influenza winter season 2007–2008]. Rapportnummer: 8354. http://www.iph.fgov.be (accessed 1 March 2011).

Gisle L, Hesse E, Drieskens S, Demarest S, Van der Heyden J, Tafforeau J . Gezond-heidsenquête België, 2008, Rapport II — Leefstijl en Preventie [Health interview survey, Belgium,2008]. Operationele Directie Volksgezondheid en surveillance, 2010, Brussel,Wetenschappelijk Instituut Volksgezondheid, ISSN: 2032–9172 — Depotnummer. D/2010/2505/16 — IPH/EPI REPORTS N° 2010/009. http://www.iph.fgov.be (accessed 1 March 2011).

Hak E, Van Essen GA, Stalman WA, et al. Improving influenza vaccination coverage among high-risk patients: a role for computer-supported prevention strategy? Fam Pract 1998;15(2):138–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fampra/15.2.138

Jacobson VJ, Szilagyi P . Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;20(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858

Thomas RE, Russell M, Lorenzetti D . Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;8(9). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858

Szilagyi P, Bordley C, Vann JC, et al. Effect of patient reminder/recall interventions on immunization rates: a review. JAMA 2000;284(14):1820–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.14.1820

Thomas RE, Russell M, Lorenzetti D . Systematic review of interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older. Vaccine 2010;28(7):1684–701. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.067

Ndiaye S, Hopkins D, Shefer A, et al. Interventions to improve influenza, pneumococcal polysaccharide, and hepatitis B vaccination coverage among high-risk adults. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2005;28(5):248–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.016

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination and self-reported reasons for not receiving influenza vaccination among Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 years—United States, 1991–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53(43):1012–15.

Baeten R . Griepvaccinatie, de centrale rol van de huisarts [Influenza vaccination, the central role of the general practitioner]. Vaxinfo 2008;51:1.

Leads from the MMWR. Adult immunization: knowledge, attitudes, and practices — DeKalb and Fulton Counties, Georgia. JAMA 1988;260(22):3253–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1988.03410220023007

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Dianne Goeman

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

Funding None.

The authors thank all the participating family physicians for the registrations and also like to thank Lieve Van de Block and Erwin Van De Vyver for their cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IVR: conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision. JV: design, analyses and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision. RB: statistical analyses. SD: interpretation of data and critical revision. DD: critical revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Appendix 1. Questionnaire

Appendix 1. Questionnaire

Date:____________ Gender:____________

Date of birth:__________ Age:____________

Do you belong to one of the following groups? If so, please colour the bullet(s).

-

People with chronic lung problems (e.g. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, asthma, …)

-

People with chronic heart problems (e.g. heart attack, angina, arrhythmia, valve problem, …)

-

People with chronic liver problems (e.g. chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, …)

-

People with chronic kidney problems (e.g. kidney failure, dialysis)

-

Diabetes patients

-

People with chronic problems of their immune system (e.g.chemotherapy, radiotherapy, …)

-

Employee in the health sector

-

Pregnant woman — second or third trimester

-

I do not belong to any of these groups

Have you ever received a flu vaccine in the past?

-

Yes

-

No

-

I do not know

Do you want to be informed about the possibility of flu vaccination?

-

Yes,

If yes, please continue on the next page.

(Even if you are vaccinated annually)

(Even if you do not belong to any of the groups mentioned above)

-

No, not even in the future.

You have completed the questionnaire, and may deposit it in the letter box or hand it over to your physician.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Rossem, I., Vandevoorde, J., Buyl, R. et al. Notification about influenza vaccination in Belgium: a descriptive study of how people want to be informed. Prim Care Respir J 21, 308–312 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00012

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00012

This article is cited by

-

Frühsommer-Meningo-Enzephalitis (FSME) und FSME-Schutzimpfung in Österreich: Update 2014

Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (2015)