Published online Jun 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7602

Revised: February 19, 2014

Accepted: April 8, 2014

Published online: June 28, 2014

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common neoplasia in the Western countries, with considerable morbidity and mortality. Every fifth patient with CRC presents with metastatic disease, which is not curable with radical intent in roughly 80% of cases. Traditionally approached surgically, by resection of the primitive tumor or stoma, the management to incurable stage IV CRC patients has significantly changed over the last three decades and is nowadays multidisciplinary, with a pivotal role played by chemotherapy (CHT). This latter have allowed for a dramatic increase in survival, whereas the role of colonic and liver surgery is nowadays matter of debate. Although any generalization is difficult, two main situations are considered, asymptomatic (or minimally symptomatic) and severely symptomatic patients needing aggressive management, including emergency cases. In asymptomatic patients, new CHT regimens allow today long survival in selected patients, also exceeding two years. The role of colonic resection in this group has been challenged in recent years, as it is not clear whether the resection of primary CRC may imply a further increase in survival, thus justifying surgery-related morbidity/mortality in such a class of short-living patients. Secondary surgery of liver metastasis is gaining acceptance since, under new generation CHT regimens, an increasing amount of patients with distant metastasis initially considered non resectable become resectable, with a significant increase in long term survival. The management of CRC emergency patients still represents a major issue in Western countries, and is associated to high morbidity/mortality. Obstruction is traditionally approached surgically by colonic resection, stoma or internal by-pass, although nowadays CRC stenting is a feasible option. Nevertheless, CRC stent has peculiar contraindications and complications, and its long-term cost-effectiveness is questionable, especially in the light of recently increased survival. Perforation is associated with the highest mortality and remains mostly matter for surgeons, by abdominal lavage/drainage, colonic resection and/or stoma. Bleeding and other CRC-related symptoms (pain, tenesmus, etc.) may be managed by several mini-invasive approaches, including radiotherapy, laser therapy and other transanal procedures.

Core tip: Colorectal cancer is a common neoplasia with considerable morbidity/mortality. Every fifth patient presents with metastatic disease, which is usually not resectable. In asymptomatic patients, new chemotherapy regimens allow long survival and, potentially, conversion of non resectable liver metastasis in resectable ones, with a significantly improved prognosis. Obstruction is traditionally approached by colonic resection, stoma or internal by-pass, although nowadays stenting is a feasible option. Perforation is associated with the highest mortality and is mostly managed surgically, by lavage/drainage, colonic resection and/or stoma. Bleeding and other symptoms (pain, tenesmus) are managed mini-invasivally by radiotherapy, laser therapy and other transanal procedures.

- Citation: Costi R, Leonardi F, Zanoni D, Violi V, Roncoroni L. Palliative care and end-stage colorectal cancer management: The surgeon meets the oncologist. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(24): 7602-7621

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i24/7602.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7602

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer (estimated 1.23 million cases per year) and the fourth cancer-related cause of death (609 thousands deaths per year) in world population[1]. Ten-fold differences in incidence between the different regions of the world, being the highest in Australia, Western Europe and North America, are reported[1].

Although death rates of CRC continue to decline since the late eighties, approximately 18%-20% of patients affected by CRC present with distant metastasis[2,3], with slight increase in the last two decades[3]; of them, only 16%-21% are suitable for potentially curative management by resective surgery and neodjuvant/adjuvant therapy[4,5].

Traditionally managed surgically, by resection of the primitive tumor, intestinal bypass or stoma[6-8], the palliative approach to incurable stage IV CRC patients has significantly changed over the last three decades and is nowadays multidisciplinary, with a pivotal role played by chemotherapy (CHT)[9-11]. Such a multimodal management of incurable CRC is responsible for a significant increase in survival of patients affected by incurable CRC in general, which has passed from 8 to 14 mo over the last two decades[3], but has been reported to exceed two years in selected populations following the sequential use of various lines of treatment including the newest chemotherapeutic agents[12,13].

Differently from potentially curable patients, where overall survival and disease-free survival are the main outcome and measured variable of any treatment, the short residual life of these patients radically change the perspective. Although the overall survival (or “quantity of residual life”) is still one of the main endpoint of any palliative treatment, indeed, it should be emphasized that the other main endpoint of management is the “quality of residual life”, which can be severely affected by surgery, CHT, and any other palliative treatment. From such a changed point of view, individual, psychological, ethical issues gain importance in deciding for the best management of any singular patient.

Traditionally used to define the management of patients with CRC disease not curable with radical intent and inevitably leading the patient to death in a matter of months/few years, the concept itself of “palliative” has changed in recent years, following the progress of CHT and surgery of CRC and distant metastasis.

The multimodal approach to initially non-resectable liver metastasis, including systemic CHT[12,14,15], intraarterial CHT[16,17], portal embolization[18,19] and secondary surgery[20,21], and its impact on survival[22], will be treated in a dedicated paragraph.

Extrahepatic CRC metastasis do not systematically imply a palliative management anymore, either. Synchronous/metachronous lung metastasis are nowadays considered suitable of surgical resection[23-25]. The indication to resection of CRC liver metastasis with local lymph node involvement is currently under debate[25], but specialized centers report patients with liver pedicle node involvement to have a 25%-5-year-survival after surgery[26]. The indication to surgical resection of other extrahepatic CRC disease, in particular peritoneal metastasis, is also matter of debate: peritoneal carcinomatosis, once considered a prognostic criterion of dismal prognosis and a contraindication to surgery[27,28], may be nowadays managed by a multidisciplinary approach including cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy[29,30], thus achieving a 5-year-survival rate of 10%-30%[30-32].

Significantly, the latest version of the National Comprehensive Cancer Group[33] and very recent guidelines[25,34], propose a systematic re-evaluation for “conversion to resectable” every 2 mo during CHT course of patients with initially unresectable synchronous liver and/or lung metastases. Although such new perspectives and modalities of treatment have a potentially curative purpose and are not treated in the present paper, nevertheless, they represent the paradigm of a “moving frontier” between curative and palliative management of advanced CRC patients.

Although it is not among the aims of the present paper, imaging modalities for resectability assessment are briefly summarized. Liver assessment is usually performed by several examinations, including Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), contrast-enhanced ultrasounds (CEUS), 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and PET/CT[35-38], as surgical decision-making requires information from multiple imaging modalities. MRI is reported to be superior to CT in the preoperative evaluation of colorectal metastasis both in normal liver[35], where it has higher sensitivity (95.6% vs 74.8%) and specificity (97.2% vs 81.1%), and in post-CHT liver[36], where MRI is reported to have a sensitivity of 85.7% compared to 69.9% of CT. MRI also shows the best effectiveness in nature characterization of hepatic lesions together with CEUS[37]. PET, PET/CT and transparietal US are also diffusely used for diagnosis, staging and follow up[35,36].

Usually diagnosed endoscopically, primary CRC resectability is normally assessed by CT[38], endoscopic ultrasound[39] and MRI[40], these two latter having a pivotal role in defining the resectability of rectal cancer. Identifying peritoneal metastasis by imaging is one of the major issues in advanced CRC. Although recent efforts in defining new radiologic criteria for diagnosis[41], the performance of CT scan[42,43] and PET/CT[43] is limited in the absence of ascites and obvious supra-centimetric tumor deposits on the peritoneum. Thus, peritoneal metastasis is still, often, an intraoperative diagnosis.

Other extrahepatic, extrapulmonary disease is normally diagnosed by organ-specific imaging modalities, although whole-body CT[44], PET[44,45] and PET/CT[46] have been proposed to systematically rule out distant metastases.

First appeared in scientific literature in the mid-twentieth century[46,47], the management of incurable metastatic CRC still represent a matter of debate among oncologists, and surgeons. Through seven decades, several “surgery-focused” papers addressed the issue of efficacy of primary CRC resection in prolonging survival. Unfortunately, most of those papers were single-center, small-sized, retrospective series, extremely heterogeneous concerning patients, clinical scenarios and setting, metastatic pattern, primary tumor location, and management (surgery, CHT, stenting etc.)[27,47-53]. In the absence of randomized trials, in recent years, the efficacy of colonic resection has been assessed by larger retrospective series, metanalysis and literature reviews[54-56]. More recently, since the late eighties, the introduction of new chemotherapic agents in stage IV patients has given rise to a prolific “CHT-focused” literature, evaluating CHT regimens by high-quality, multi-centric, prospective randomized trials[9,11-13,57].

Interestingly, in “surgery-focused” papers, also owing to the retrospective nature, CHT is often analysed as one of the possible variables potentially affecting survival, but it is usually considered as a whole (regardless of the CHT regimen administered)[5,27,50,58-62]. On the contrary, “CHT-focused” articles do not even report whether patients undergo surgery (resective or non-resective) of primary CRC, and consequently do not evaluate surgical resection as a parameter potentially prolonging survival[9-13].

As a matter of fact, such a various literature on the subject, prevent even nowadays from definitive conclusions concerning the best approach to incurable stage IV patients, in particular concerning the role of palliative resection of the primary CRC.

Patients with incurable CRC may be asymptomatic or present with a variety of symptoms and clinical scenarios ranging from moderate anaemia to digestive troubles, to lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding to life-threatening conditions, including obstruction and perforation, needing emergency management.

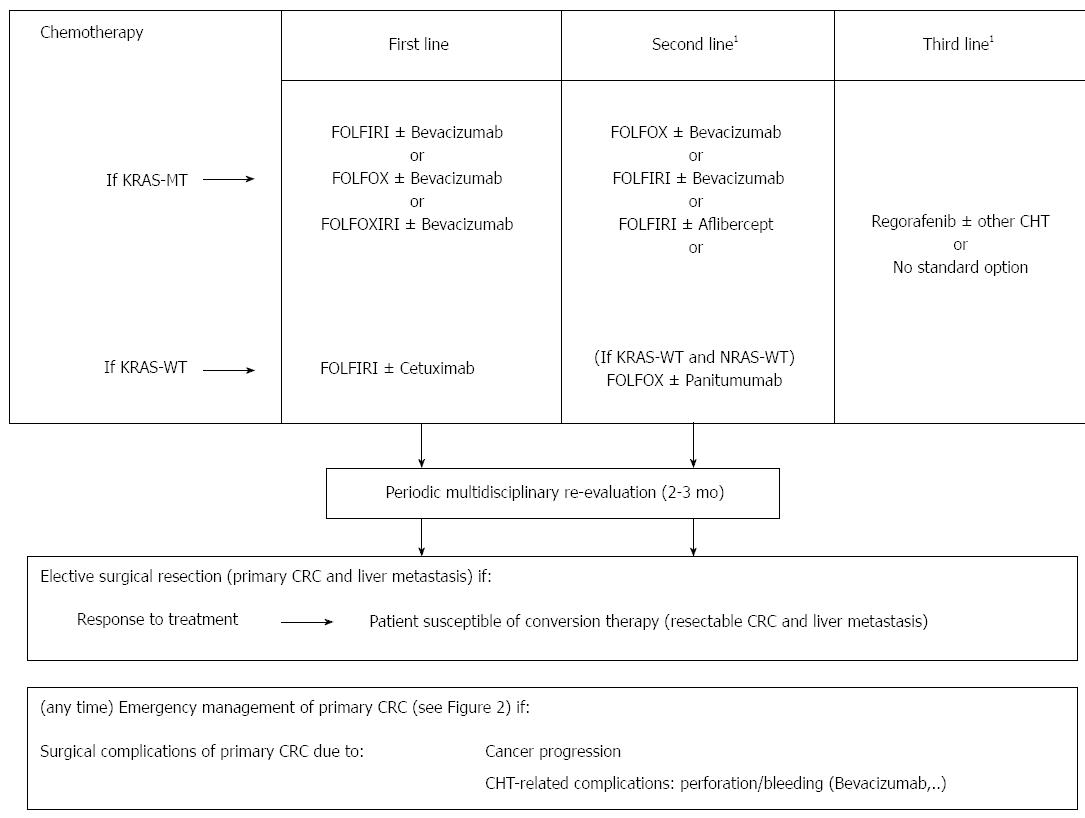

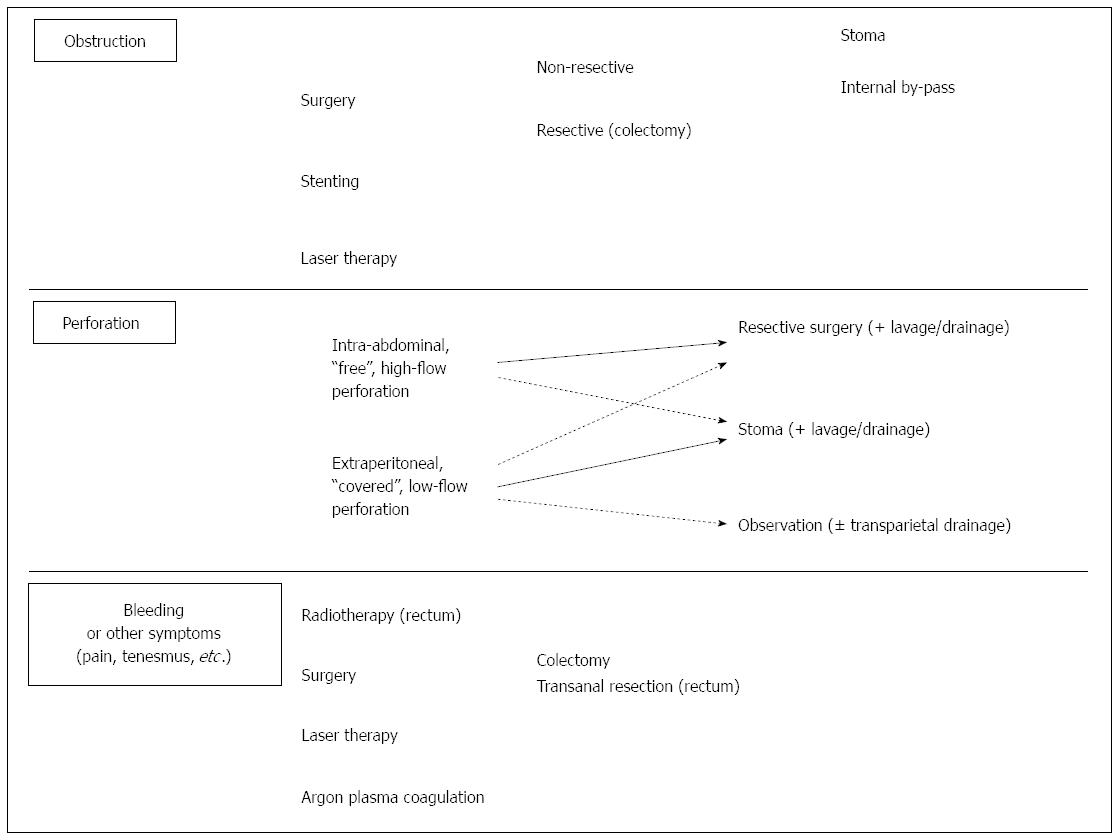

In order to allow a rational and practical organisation of the present review, here we present two flow charts (Figures 1 and 2) based on clinical relevance of CRC at presentation, since the approach to the patient changes radically. In fact, in asymptomatic patients, the management is aimed to slow down cancer progression, thus prolonging long-term survival and preventing cancer-related complications. Differently, in emergency and severely symptomatic patients, it is focused in solving cancer-related complications, which may be rapidly fatal or imply intolerable symptoms. Obviously, the two proposed managements are not indefinitely exclusive, as an emergency patient may become asymptomatic after a life-threatening condition has been treated, and, conversely, an asymptomatic patient may become severely symptomatic under CHT.

This simplification does not to consider rarer, non emergency symptoms that may become invalidating and finally lead to surgery, including hyperpyrexia or pain due to compression (“bulk-effect of tumor”) or infiltration of nervous plexuses or contiguous organs (ureters etc.). Moreover, this review does not consider comorbidities, which can finally play a determinant role in deciding the management, and does not consider that the majority of patients presents with an intermediate clinical picture, where often the greatest challenge is “to decide the right timing” to turn to a more aggressive management, indeed. This paper is aimed to address the issue of “what” to do according to a specific clinical situation, whereas “when” to proceed is still (and probably will ever be) a medical decision on a case by case basis.

In recent times, the main role in the management of non-emergency patients affected by incurable CRC has passed from surgery to CHT. Accordingly, international guidelines suggest nowadays to avoid surgery in the case of patients with incurable metastasis from CRC, unless in the presence of (or in the imminent risk of) complications such as obstruction or significant bleeding[33].

Nevertheless, the approach to patients with incurable CRC is extremely various, as two thirds of them undergo surgery in United States[63], whereas they are mostly non-operated on in the Netherlands[64]. Probably, several factors play a role in deciding to explore surgically (and to resect the tumor, if feasible) patients with such a dismal prognosis, including the belief/perception of prolonging survival, preventing complications, improving quality of life, and having a positive psychological effect on the patient[27].

Although the purpose of the paper is not technical, here we present a brief summary of the surgical procedures performed for palliation.

Non-resective procedures performed for advanced CRC may be summarized in so-called “exploration” laparotomy/laparoscopy, stomas and internal by-passes.

Laparotomy/laparoscopy exploration: Usually performed in the midline, laparotomy is aimed to verify the correctness of preoperative CRC diagnosis/staging and to manage cancer. Not rarely, laparotomy is performed as the last “diagnostic tool” before renouncing to any other procedure[27,28] and eventually results in the only surgical act performed (as the indication to surgery is not confirmed intraoperatively). Laparotomy may allow for intraoperative diagnostic procedures (such as US or biopsy of primary CRC, nodes or carcinosis) aimed to better define CRC stage/histology and further therapeutic strategy. Although, in these cases, laparotomy just addresses the first purpose of surgery (diagnosis/staging), nevertheless, it generally implies a general anaesthesia and an abdominal incision (port-site incisions for laparoscopy), which are not negligible acts in end-stage CRC patients. Since healing process may be poor in end-stage CRC, and neoplastic ascites may predispose to eventrations and early ventral hernias, the abdominal wall should be accurately closed plane by plane. In general, it should be reminded that any complication, even minor, may significantly affect the short residual life. Laparoscopy may be as effective as laparotomy[65] with better early outcome and less long-term complications[66,67].

Stomas: Stomas are usually fashioned as “loop stomas” (one exception is after Hartmann procedure) by pulling the ileum or the colon through a full-thickness incision preferably passing through the rectum muscle. It is ideally placed at an adequate distance from the umbilicus, the superior iliac spine and the 10th rib, where it carries the lesser risk of parastomal hernia/prolapsus and allows for the best postoperative management.

Differently from ileal stomas, that present the main drawback of high volume, very irritating, liquid stools, colonic stomas have the advantage of lower-volume, solid stools, are normally easier to manage postoperatively and have lower morbidity, thus representing the ideal solution for palliation[68]. Normally performed in the transverse colon or sigma, stoma fashioning may be preceded by laparoscopic exploration, which can facilitate the dissection of the chosen segment and the identification of the colostomy placement[69]. Whenever general anaesthesia is contraindicated, stomas may also be performed under spinal or loco-regional anaesthesia in the lower abdomen.

Internal by-passes: Internal by-passes are usually performed for colon cancer through laparotomy by manual (or partially mechanical) latero-lateral anastomosis between the ileum/colon proximal to obstructing tumor and the colon distal to tumor. Since colonic obstruction is normally associated to ileal and/or colonic distension, performing laparoscopically such an anastomosis should be considered a very demanding procedure and reserved to experienced laparoscopic surgeons[66].

Resective surgery for palliation[27,47,70,71] include classic procedures performed for CRC, such as right colectomy, left colectomy, Hartmann procedure (left segmental colectomy associated with proximal stump colostomy and closure of the distal stump), proctocolectomy, low anterior resection and abdominoperineal resection. Since technical standards for palliative CRC resection are not the same as for curative ones, limited colonic resections (including ileocecal resection and segmental colectomy) are generally accepted, being margin-free, R0 primary CRC resection the main criterion to be respected. Moreover, D2 lymphadenectomy required for oncological reasons and correct staging, including the dissection of vascular pedicles at the origin and the total mesorectal excision (for rectal tumors), is not needed in the case of palliation.

Nevertheless, the “safety rules” to perform a leakage-free anastomosis have to be respected. The vascularisation of the colonic remnant must be respected, and any manoeuvre aimed to avoid any tension at the anastomosis-site should be performed, including colonic dissection and inferior mesentery vein division, if needed. The anastomosis should be performed avoiding any contamination of the abdomen and abdominal wall, which should be adequately protected, since both neoplastic cell dissemination and infectious complications may occur.

Extended resections for CRC infiltrating contiguous organs, including anterior and posterior pelvic exenteration[72,73], and hemicorporectomy[74] are not indicated in a palliative context anymore.

Transanal procedures are discussed in the paragraph dedicated to bleeding and other symptoms.

Strategy in surgical palliation: Several variables play a role in deciding the procedure, including patient’s status, clinical scenario and setting, need/availability/timing of adjuvant treatments, R0 resectability of the primary CRC, site of primary CRC, attitude and beliefs of medical team. Importantly, if the non-resectability is due to distant metastasis, technical difficulty of resection is comparable to curative surgery, whereas, if the reason of non resectability is the primary, surgery may results in a very challenging situation. CRC site also influences the surgical strategy also concerning the type of surgery (resective vs non-resective). In fact, clinical impact and morbidity of CRC resection are generally considered to increase from proximal to distal, being maximum for the lower third of the rectum. Palliative ileocecal resection is considered a low-complexity, short-lasting procedure which may be accomplished even under spinal anaesthesia, thus reducing the stress of surgery. On the contrary, left-sided procedures are more time-consuming and associated to higher morbidity[75], including leakage and pelvic abscess[76].

Rectal cancer deserves a particular mention. Also owing to intrinsic technical difficulty and morbidity of surgery, and the fact that stoma is often necessary (thus cancelling one advantage of resection), deciding to perform a palliative resection of low rectal tumors should be carefully pondered. The resective options are: Hartmann procedure (HP), low anterior resection (LAR), and abdomino-perineal resection (APR). Since APR implies a perineal wound which is associated to healing complications in roughly one half of the patients[77], sphincter-preserving techniques are generally preferred. Differently from HP and APR, which imply a colostomy, this latter is not systematically performed after LAR for cancer of the upper rectum, whereas it is preferably fashioned (with protective purpose) after high-risk, “low” colorectal anastomosis. According to Fazio[78], in any case stoma is not avoided, the indication to resection should be carefully pondered against palliative stoma (without resection) whenever patient’s supposed survival is not superior to 6 mo. For all these reasons, the general attitude is to be more aggressive for proximal tumors, and more oriented towards non-resective procedures for distal tumors.

CRC extirpation and survival: In patients presenting without significant clinical symptoms or emergency conditions, the main question is whether they may benefit from primary CRC resection or a less aggressive management should be preferred.

Since 1949[6], the debate as to the real effectiveness of palliative resection of primary CRC in prolonging survival has not given a definitive answer. Although, in the pre-CHT era, most authors[8,47,79,80] described a 10.6-15 mo and 3.4-7 mo mean survival after resective and non-resective management, respectively, selection biases challenge the validity of those results, since non-resective procedures were mostly performed whenever resective surgery was not technically feasible or contraindicated by poor general conditions, thus resulting as being the only option allowed[6,8,29,47,79-81]. In order to overcome such bias and answer the question regarding the indication to surgical resection when possible, our group selectively, although retrospectively, compared the overall survival of primitive CRC resection vs non-resective procedures in resectable patients, finding that resection was related to a 46% 1-year-survival (vs 17%)[28].

Since the nineties, the massive introduction of CHT in this class of patients, and the development of more and more effective CHT regimens, has rekindled the debate regarding the indication to palliative surgery in patients already undergoing a potentially non-inferior, less aggressive management. Significantly, in their systematic review of papers comparing survival of patients undergoing the resection vs non-resection of the primary tumor, Verhoef et al[82] found that the resection of primary CRC was related to better prognosis in all papers including no (or very few) patients undergoing CHT[27,47,79], whereas results were more ambiguous in series including patients undergoing CHT, where resective surgery resulted as being related to survival in some papers[50,83-85] but not in others[48,52,53,61,70,86]. Since then, other papers specifically addressing this issue (is CHT + resective surgery superior to CHT alone) somehow confirmed such an incertitude, concluding in favour[5] or against[62] the use of surgery in such a class of patients. In particular, our group[62] analysed the prognosis of four groups of patients selected by coupling type of surgery (resective/non-resective) and CHT policy (CHT/non-CHT); interestingly, resective surgery associated to CHT did not show any advantage over CHT alone in terms of survival. Since the results were confirmed in “technically” resectable patients, we concluded that, even when feasible, surgical resection is not indicated in asymptomatic patients. An ongoing randomized controlled multicenter trial (SYNCHRONOUS - ISRCTN30964555)[87] is now addressing the issue of short- and long-term outcome after the resection of the primary tumor vs no resection prior to systemic therapy in patients with colon cancer and synchronous unresectable metastases (UICC stage IV).

Differently from procedures achieving an R0 resection (no residual neoplastic tissue left after resection), leaving residual neoplastic tissue (R1, R2) is related to the same dismal prognosis as no resection[5]. Since, in this latter case, the patient should suffer the drawbacks of both major colonic resection (high morbidity) and non-operative management (short survival), the abstention from CRC resection should be strongly recommended whenever an R0 resection may not be achieved.

Several others criteria have been found to be related to a poor prognosis or poor surgical outcome, thus being considered to be arguments against major surgical resection. Major liver involvement[5,8,50,86], otherwise described as extensive (bilobar) liver involvement[27], hepatic parenchymal replacement by tumor > 25%[88] or > 50%[47], and old age, variously intended as ≥ 65 years[27,88], ≥ 70 years[3], ≥ 80 years[89], have been related to a poor survival and are currently proposed as a strong contraindication to major colonic surgery. Other parameters, including poor differentiation[5,25], high serum levels of CEA[47,88] or lactic dehydrogenase[85,88] have been also related to poor outcome.

Perioperative mortality and morbidity: Higher perioperative mortality and morbidity of CRC resection represent the counterpart of a supposed longer survival. Such an issue may be supposed as being even underestimated, since an intrinsic distress due to major colonic surgery with respect of clinical observation is undeniable (although never measured) and may be supposed to significantly affect the residual life. Excluding emergency surgery, perioperative mortality for colonic resection for incurable CRC is reported to vary widely, ranging from 0% to 14%[5,27,47,53,59,79,90], and exceeding 8% in several studies[27,47,59,90,91]. Morbidity of elective resective surgery varies widely through series, too, ranging from 18% to 50%[27,48,53,79,85,86].

Since 2000, laparoscopic surgery has been widely adopted in order to reduce the aggressiveness of surgery in incurable CRC patients[92-99]. Although a minimally invasive approach may seem intuitively not the main issue in patients with dismal prognosis, on the contrary, a prompt recovery during the weeks following surgery may significantly improve the quality of residual life. As already observed in other fields of laparoscopy, a recent systematic review[56] found that laparoscopy allowed, in front of a prolonged operative time time (median 180.5 min vs 148 min), lesser blood loss (127.5 cc vs 180 cc) and a shorter hospital stay (9.3 d vs 15 d). Although only two of reviewed papers[96,97] found a difference in postoperative complication-rate, the pooled odd ratio allowed the authors to report a significantly lower morbidity after laparoscopy (19.5% vs 26.9%), whereas mortality was the same[56]. Altered anatomy and tissues due to advanced CRC disease (and intrinsic technical limits of laparoscopy in dealing with them) represent a potential critical issue of laparoscopy, potentially increasing the rate of procedures “converted” to laparotomy, with the following significant reduction in the benefits of a mini-invasive approach. Interestingly enough, although in some cases it is reported to reach 26.5%[93], the median 13% conversion-to-laparotomy rate is consistent with the 14%-17% reported for “curable patients”[100,101], thus confirming that laparoscopy may have a role in advanced CRC management.

Indeed, when deciding whether to resect or not, morbidity/mortality of surgery should be compared to the complication-rate due to primary tumor progression in patients not undergoing surgical resection as initial treatment (but just CHT). Interestingly, CRC-related morbidity results as being 11.7%-29% in patients not undergoing surgery, intestinal obstruction being the most frequent (range 8.7%-21.7%)[48,50,52,53,102], whereas there is obviously no surgery-related mortality.

Moreover, it should be considered that surgical resection of the primary CRC may affect the following management by modifying CHT administration schedule: on one hand, complications of surgery may lead to a delay in CHT administration, in some cases out of the “therapeutic window” of CHT after surgery (usually 4 to 6 wk), with the consequent potential impact on survival; on the other hand, in the case of an uneventful recovery after surgery, the patient may be supposed to avoid any primary CRC-related complication during CHT administration, when a suspension of CHT may lead to a reduced response and an emergency procedure may carry the highest perioperative risk. Pros and cons of operative and non-operative attitudes are difficult to assess, as they are likely to be related to the peculiar characteristics of the patient, tumor, and planned surgery.

In general, from the comparison of those numbers, it seems realistic to consider that the “price” of surgical resection in patients with an incurable CRC is a death every 15-20 patients and a morbidity not inferior to that of a non-operative management. Although perioperative morbidity of surgery and long-term morbidity of a conservative management are not homogeneous and therefore difficult to compare, nevertheless, we believe that surgical resection is not systematically indicated in asymptomatic patients in general, and may be ideally proposed to selected patients, in particular those so-called “long-term survivors”. Based on our and other authors’ experience[5,8,50,86,89], patients with old age and major liver involvement, should be at least accurately evaluated before an elective primary tumor resection, since they are “short-survivors”.

Secondary surgery after CHT-induced “conversion” from non-resectable to resectable liver metastasis: Although curative management is not the aim of this review, nevertheless, the possibility to switch from a palliative context to a curative one is the most intriguing aspect of metastatic CRC management and will be briefly treated. Since, in 2004, Adam et al[20] first showed that the 5-year-survival rate of patients undergoing secondary resection was comparable to that of primary resection, resectability of liver meatastasis has become one of the purpose of new CHT agents. Since, liver metastasis resectability has been reported to increase to 30%-32% under doublet regimens (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI)[20,103], to 36% under FOLFOXIRI[14], to 40% when bevacizumab is added to XELODA (oxaliplatin and capecitabine)[104]. Conversion rate of non-resectable, non-WT-KRAS patients was retrospectively reported to be as high as 60% when Cetuximab is added to FOLFIRI[105], but more recent randomized trials have reported a more realistic 16%-27.9% when Cetuximab is associated to FOLFOX/FOLFIRI/XELODA regimens[106,107].

Other than systemic CHT, also intraarterial CHT[16,17] may allow reducing CRC metastasis in number and size, thus allowing for downstaging, whereas portal vein branch embolization/ligature of liver segments affected by CRC metastasis may lead to hypertrophy of the remaining parenchyma whenever non-resectability is determined by a too small (< 25%-30%) liver remnant, thus allowing delayed resection[18,19].

Finally, the improvement of liver surgery[20,21] has allowed a 20%-64% morbidity and 0%-2% mortality of secondary resection of CRC metastasis on post-CHT liver, which is comparable to those achieved after primary surgery. Significantly, 5-year-survival of patients undergoing secondary liver surgery after downstaging is comparable, although not the same, to that of primary surgery of resectable disease (33% vs 46%) according to an international database[22], although very wide ranges of 5 years survival (33%-50%), disease-free survival (8.7-17 mo) and overall survival (36-60 mo) are reported in the literature following various CHT regimens[21].

Such a radical change of perspective on the subject has evident implications in patients’ management and expectations, as a 4.2%-22.5% of “supposed palliative” patients may finally survive[21,22]. The price of such a “never say never” attitude is a bi-monthly, multidisciplinary re-evaluation of liver metastasis under CHT by CT scan, MRI or US[33,34], as resectability has become the primary aim of treatment[34].

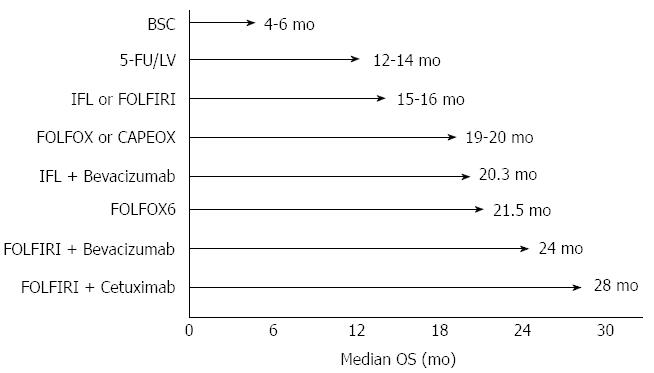

Medical treatment for colon cancer has been radically modified in its aims and modalities in the last 30 years: the dramatic evolution of researches and discoveries in this field led to significant improvements on overall survival (OS) (Figure 3) and strongly modified the concept of curability of the disease.

From the eighties to the nineties, with studies on fluoropyrimidines, some steps have been made towards a chemotherapeutic regimen active in advanced CRC[9,108-111]. These trials analyzed the use of infusional or bolus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) combined with folinic acid (FA) or levamisole, with different modulations; the results showed an enhanced effectiveness of 5-FU when combined with high-dose folinic acid, finally identifying a bimonthly schedule with continuous infusion of 5-FU after bolus as the more effective and less toxic schedule[111]. The same trials showed an overall response rates (RR) of 39%-54.1% with a median overall survival (mOS) of 12-18 mo and a progression free survival (PFS) of 14.5 mo[9,108-111]. A further trial showed the equivalence between oral 5-FU (capecitabine) and infusional 5-FU[112]. During this long period of time, chemotherapy was considered as a palliative treatment and was administered only when surgery was no longer possible due to the presence of locally advanced or metastatic disease.

After years of attempts and modulation of approaches with fluoropyrimidines, a turning point was determined by the introduction of new drugs to be administered in association. The exploration of the activity of chemotherapeutic doublets with irinotecan and 5-FU was performed since the early 2000s in large randomized phase III trials[10,113-115], establishing a new survival standard for metastatic CRC. Douillard et al[113] and Saltz et al[10,114] showed the superiority of FOLFIRI regimen compared to 5-FU bolus plus FA[10,113] and to irinotecan alone[114] in terms of PFS and OS. Saltz et al[114] reported a PFS of 7 mo and a mOS of 14.8 mo (ORR = 39%), whereas, similarly, Douillard et al[113] obtained a TTP of 6.7 mo, an OS of 17.4 mo and an ORR of 35% and Fuchs et al[115] reported a PFS of 7.6 mo and a mOS of 23.1 mo.

At the same time, de Gramont et al[11] compared the association of oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidines (oxaliplatin plus 5-FU/FA or FOLFOX) with 5-FU/FA alone, showing a significant RR increase of 50.7% and PFS prolonged to 9 mo, with a mOS of 16.2 mo (without reaching statistical significance on mOS endpoint). Few years later, Goldberg et al[116] found a superiority of FOLFOX regimen compared to irinotecan/oxaliplatin and bolus IV 5-FU, both considering effectiveness and safety. In more recent years, capecitabine was evaluated in association with oxaliplatin (XELOX) as an orally-administrated alternative to 5-FU in order to improve patient’s compliance, showing similar effectiveness and safety than FOLFOX regimen[117,118].

Through the first decade of 2000s, the choice concerning which one between oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based regimens should have been employed as first or second line became a matter of debate. Several studies confirmed FOLFOX and FOLFIRI treatment as being equally effective as first line treatment, with comparable RRs and PFSs[57,119]. Colucci et al[119] compared FOLFIRI with FOLFOX as first line, reporting no differences in OS, ORR and toxicity; Tournigand et al[57] compared FOLFIRI and FOLFOX regimens in first and second line of treatment in order to identify the best sequence: although no significant difference in effectiveness and safety was recorded, the two regimens showed a different toxicity profile, FOLFOX being more often associated to neurotoxicity whereas FOLFIRI to mucositis, alopecia and diarrhoea.

In 2007, Falcone et al[14] first compared the association of 5-FU, irinotecan and oxaliplatin (FOLFOXIRI) with FOLFIRI, showing an increased RR (66% vs 41%), PFS (9.8 mo vs 6.9 mo) and OS (22.6 mo vs 16.7 mo), in spite of a slightly increased toxicity (mostly neurotoxicity, neutropenia and diarrhea). Interestingly, a significantly higher number of patients undergoing FOLFOXIRI regimen underwent secondary resection of pre-treatment non-resectable liver metastasis (36% vs 12%). Such a study represented a turning point, suggesting this regimen as a valid option to improve the outcome of a selected group of patients with good performance status, also by converting metastatic disease from non-operable to operable.

From target to tailored therapy: In the last decade, the intrinsic and acquired resistance of metastatic colon cancer to chemotherapy, on one hand, and the evolution of target identification through translational medicine, on the other, are paving the road to patient-tailored therapy for metastatic CRC, aiming to cure patients basing on the complex interactions among patient’s characteristics, disease physiopathology and drugs’ metabolism.

The understanding of biological mechanisms at the basis of the disease and the discovery of molecular pathways leading to CRC progression have led to the development of new targeted drugs against CRC. In particular, bevacizumab (a humanized antibody anti-circulating vascular endothelial growth factor - VEGF-A) and cetuximab (a recombinant antibody anti- epidermal growth factor receptor - EGFR) have been introduced in advanced CRC in association with poli-chemotherapic regimens. The first performed trials evidenced statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in terms of OS, PFS and RR, by adding bevacizumab to oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based regimens with an easily manageable additional toxicity[15,120,121]. Hurwitz et al[15] first studied the association of bevacizumab with 5-FU bolus with FA (vs 5-FU bolus with FA alone), showing an increase in RR (44.8% vs 34.8%), PFS (10.6 vs 6.2) and mOS (20.3 mo vs 15.6 mo). Saltz et al[120] also showed an increase of PFS following the administration of bevacizumab in patients receiving FOLFOX.

Since 2009, the association of cetuximab with FOLFIRI[12] or with FOLFOX regimens[122] was reported to increase PFS whereas the increase of OS did not reach statistical significance in metastatic colon cancer. More recently, the OPUS study[106] showed that the benefit was limited to patients with KRAS wild-type (WT) tumors, confirming KRAS mutation status as a predictive biomarker. This latter result was confirmed by a pooled analysis[123], which also reported a significant improvement in OS (HR = 0.81; P = 0.0062), PFS (HR = 0.66; P < 0.001) and ORR (OR = 2.16; P < 0.0001). Some new evidence in favour of cetuximab in a prospectively selected series of WT-KRAS patients emerged from a very recent study presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2013 Annual Meeting[13]. From this large trial, the combination of cetuximab and FOLFIRI resulted more effective than the combination of bevacizumab and FOLFIRI in a population of WT-KRAS metastatic colon cancer patients, both considering ORR and OS (28.7 mo vs 25 mo).

An alternative agent proposed in the first line therapy for WT-KRAS patients is panitumubab[107], which has been observed to prolong overall survival from 20.2 mo in the FOLFOX4-alone group to 26.0 mo in the panitumumab-FOLFOX4 group.

Future development and open issues: New agents have already showed promising results after the failure of conventional CHT. Aflibercept[124], a soluble fusion protein with high affinity for VEGF-A, -B and PlGF, has been associated to a 1.5-mo-increase of OS after first line FOLFIRI. Regorafenib[125], a multi Tyrosin Kynase Inhibitor (TKI), in association with FOLFIRI has been found to prolong survival by 1.4 mo in heavily treated patients: trials are ongoing to identify the best management of these drugs.

The extensive study of genoma in CRC is ongoing. Several genes, including BRAF[101], NRAS[126], PI3K[126,127], MEK 1/2[127] and PTEN[128] are currently studied as their mutation seems to be related to poor prognosis in CRC patients undergoing CHT. New agents, including pimasertib, have been evaluated by preclinical studies, showing promising results[127].

As a natural consequence of the recent trend towards multifaceted treatment and patient-tailoring, different strategies and sequencing of chemotherapy have been explored in the advanced disease. “Treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity” has been the standard practice until now, but a new approach is challenging this paradigm[129], proposing to temporarily quit CHT administration until clear progression, with no difference in terms of OS and better quality of life.

The encouraging and continuously improving results of CHT in advanced CRC management has led to extend its use to earlier CRC classes, including stage III[130] and, more recently, stage II[131,132], in accordance with the hypothesis that recurrence was likely to be due to residual cancer existing at microscopic stage. Since 1990, Moertel et al[130] reported an overall recurrence rate reduction of 41%, establishing infusional 5-FU and FA as the new standard of care for adjuvant CRC therapy, thus hypothesizing that CRC was a more chemosensitive disease than previously thought. In 2004 the MOSAIC trial[131], recently updated[132], showed an increase of 5-year DFS rates (from 67.4% to 73.3%) and 6-year OS rates (from 76% to 78.5%) when oxaliplatin is added (bolus + infusional) to 5-FU (FOLFOX) in resected stage III colon cancer. Those encouraging results in stage III CRC seem to suggest a similar benefit of fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy in Stage II, high risk patients (T4, < 12 lymph nodes harvested, emergency setting)[132,133], whereas targeted therapy seems useless in this setting[134].

The most commonly reported life-threatening complications of advanced CRC are obstruction and perforation[27,51], but also bleeding and other minor symptoms will be discussed. Indeed, unless the patient presents the typical features of acute obstruction or acute diffuse peritonitis by colonic perforation, it is often difficult to assess the real threaten to life and consequently the real need and timing of emergency surgery in the case of patients with a very limited life expectancy. Therefore, it is difficult to make any generalization and any patient should be evaluated on a case by case basis. Moreover, data from literature are extremely debatable and non-concordant, as study series are non-homogeneous concerning patients, tumors and management; nevertheless, for practical reasons, those conditions are discussed separately.

Obstruction is the most frequent condition requiring an aggressive management of patients with incurable CRC, being reported in 10%-26% of metastatic CRC[27,51,135]. This complication is typical, albeit non exclusive, of left-sided CRC (sigmoid and rectum), both for the lesser diameter of colon and different modality of growth of tumors towards stenosis. Interestingly, obstruction is less frequent in series reporting only rectum tumors[135], probably also owing to an easier access to clinical examination and diagnostic tools allowing for an earlier diagnosis.

The management of obstructing CRCs varies according to site of primary, being mostly resective for proximal tumors, whereas other options are available and may be preferred in the case of CRCs located in the sigmoid or rectum[136], including stenting[137,138] and laser ablation[139,140].

Surgery: Even more than in asymptomatic patients, the main issue of incurable CRC resection performed for colic obstruction, is not a complete lymphadenectomy, but removing the obstruction as soon as possible not causing any colonic leak in order to avoid any dissemination of neoplastic cells and infectious complications. The choice of derivative surgery also depends on tumor characteristics and location indeed, being any internal by-pass non possible for tumors arising distally to the sigmoid colon. Resective surgery is usually preferred in proximal CRC, where colostomy is not an option and internal by pass by ileo-colonic (transverse or sigmoid) anastomosis is performed for locally infiltrating tumors or carcinosis. For obstructing distal tumors, the choice between CRC resection and stoma (usually in the sigmoid/transverse colon) is more challenging (see above).

In some cases, colonic obstruction distal to the cecum usually causes a distension of the cecum itself (according to the law of Laplace), which may be increased by the continence of the ileo-cecal valve: in such a case, a concomitant ischemia/perforation of the proximal colon due to distension may occur and require multiple/extensive colonic resections or stomas. Although CRC palliative resection performed in such a setting implies the highest mortality (up to 18%[47,51,59,79,90,91]), it is often the option preferred by the surgeon especially in presence of a concomitant perforation and consequent pericolonic abscess/stercoral peritonitis (see below).

Stenting: Since the mid-90s, self-expanding metallic stents have shown to be more effective than other treatments (argon laser, plastic stent) and have been proposed in the management of colorectal stenosis in order to avoid emergency surgery[141]. Since then, stent use has been proposed with three purposes: (1) allowing a delayed, elective (rather than emergency) colonic resection in the case of “curable CRC patients”; (2) allowing a definitive, palliative solution for “non-curable patients”; and (3) avoiding a stoma. Modern self-expandable metallic stents are conceived to be incorporated into the tumor by exercising a pressure and inducing a partial necrosis in surrounding neoplastic tissue. In order to anchor the stent and to prevent any migration, colonic stents are usually clepsydra-shaped and may have various diameters and length in order to fit any neoplastic stricture. The reported rate of successful positioning of the stent is 75%-98%[137,142-146], being the main cause of failure the impossibility to pass a guidewire through the tumor, whereas the effectiveness in relieving a neoplastic obstruction is as high as 93.1%-98.7%[143-145].

Short-term complications are reported up to 14.8%[143] of cases, with a median perioperative perforation rate of 3.9%-4.5%[137,138]. Although not the most frequent, perforation is the most relevant, since it could give rise to a life-threatening acute peritonitis, with a 20%-100% mortality[138,144]. Moreover, perforation may cause the transcelomatic diffusion of CRC by dissemination of neoplastic cells[143]. According to clinical picture and entity of perforation, the management of such complication include surgery (stoma, resection) unless contraindicated by prohibitive general conditions. Other common perioperative complications are stent migration/occlusion (1.8%-9%), and bleeding (0.5%-4%), normally managed endoscopically by stent replacement and hemostasis[138,143].

Long-term morbidity of palliative stents may exceed 40%[143,144,146], with a rehospitalisation rate of 34%, and include bleeding (21%[143]) stent migration (12.5%-22%[143,144]) or occlusion (9.4%-17%[137,143,144]), whereas perforation is 3%-7%[143,144]. Late stent occlusion is usually due to cancer progression and colonization of stent neo-lumen, and therefore is manageable endoscopically and suitable of re-stenting or laser ablation. Abdominal pain and tenesmus are also observed both perioperatively and as a late complication, and are generally managed conservatively[138,143,144].

When compared to palliative, emergency surgery, CRC stenting has showed a lesser perioperative mortality (0%-4.2% vs 5%-10.5%), lower perioperative morbidity, shorter hospital stay (9.5-10 d vs 15-18.8 d)[137,143,145] and lower rate of stoma formation (54% vs 12.7%)[145]. Nevertheless, it should be remarked that every fifth patient undergoing palliative stenting finally needs some other reintervention, including re-stenting, laser ablation or colonic surgery[137,146]. Although encouraging, the retrospective nature of present literature on the subject prevents from definitive conclusions. Significantly, a high rate of severe complications following stage IV CRC stenting led to the early closure of a multicenter trial[147].

Although it may be considered a fine mini-invasive, low morbidity option for patients with limited life expectancy, nevertheless, stents’ use still has some open issues to be addressed. First, the success rate and morbidity of stenting seems to be different between the sigmoid-rectum and the remaining colon, where the intraperitoneal location and anatomic variability may be supposed to cause lower success rate and higher morbidity, including perforation[143]. The fact that, in their extended review of patients treated by stenting, Watt et al[137] found only 2% and 1% with transverse and right-sided CRCs, somehow confirms a more common use for left tumors. If we add that, owing to technical reasons, it may be difficult or impossible to stent low rectum cancers approaching to the anus, we can deduce that a not negligible part of CRCs are not suitable for stenting. Second, the long-term effectiveness of CRC stenting still have to be confirmed on a long-term basis. Stent-patency has generally been evaluated within few mo from positioning, whereas its median duration is three and half mo (106 d)[137]. Indeed, in pre-CHT era, the short life expectancy of advanced CRC led to consider stent positioning an effective, definitive palliation[48], allowing the prompt start of CHT. Nowadays, the reported long survival associated to new CHT regimens, rekindle the debate about long-term effectiveness of stents, which are also associated with a high late morbidity, also exceeding 40%[143] or even 50%[144]. Significantly, a recent meta-analysis[145] shows how the early morbidity rate is significantly higher after surgery (13.7% vs 33.7%) whereas late complications are more frequent after stenting (32.35% vs 12.7%). Such long-term results of stents prompt a double dilemma: (1) should palliative surgical resection to be preferred to stent, at least in supposed long-survivors[146] and (2) should elective palliative surgery be considered after successful stenting, or should simple observation be preferred This latter hypothesis may become even more interesting if we consider that emergency (rather than elective) surgery notably carries higher colostomy rates and that rates of primary anastomosis after elective surgery following stenting are at least twice that of those after emergency surgery[137]. The recent development of a sequential management of obstructing CRC by “bridge stenting” followed by laparoscopic colonic resection[148,149] may be considered as a feasible mini-invasive option somehow fitting the need of advanced CRC patients.

Last but not least, the positive psychological effect of not having a temporary or permanent colostomy is another positive effect of stent positioning[150].

Laser therapy and endocavitary radiation: Initially proposed for small polyps, bleeding[151] and palliation[152] in the late 70s, Neodymium yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser therapy (also called high-powered diode laser therapy) is decreasingly proposed for the palliative treatment of obstructing rectal cancer (by vaporizing neoplastic tissue) and bleeding (by inducing coagulative necrosis) in patients unfit for surgery. Laser therapy normally needs up to 5 session to be effective and has a 78%-91% success rate in treating obstruction[139,140]. A 2%-5.3%[138-140] morbidity and 1.8% mortality[140] have been reported, being colonic perforation the most feared complication. Somehow accordingly, lower morbidity and no mortality are observed when only rectal tumors are examined[139]. Some concern has been expressed about long-term results of palliation, since obstruction is reported to recur at a median of 24 wk after initial treatment, thus requiring delayed surgical palliation[139]. Such a consideration may gain interest in the light of long-survival recently observed with last generation CHT.

Endocavitary Ir-192 irradiation has been proposed since the late 70s for the palliative management of rectal cancer including obstruction[153]. During the 90s such an approach has been associated to laser therapy with 79%-100% success and 16%-44% total complications[154,155], including acute perianal pain, perianal abscess, rectovaginal fistula, suggesting that endocavitary radiation may prolong rectal lumen patency when compared to laser therapy alone[154].

Colonic perforation is mostly a potential life-threatening condition requiring emergency surgery. The mechanism of perforation in advanced CRC includes tumor necrosis[48,156,157], colonic (usually cecum) distension secondary to obstruction by distal CRC[156,157], other treatment complications, including stenting[143,144], laser therapy[139,140], transanal resection[158,159]. Such a complication has a significant mortality rate[138,140,143,156,157]. Indeed, colonic perforation may present with a wide variety of clinical scenarios, ranging from ongoing acute stercoral peritonitis to more ambiguous clinical pictures, whenever the perforation is limited or “covered”[156,157]. Although symptoms and management vary widely, also owing to site and mechanism of perforation, here we describe such two extreme scenarios. In general, sudden onset abdominal pain is a key-symptom, and should be investigated in any patient with advanced CRC even in the absence of signs of acute peritonitis or hyperpyrexia. CT scan is mandatory, possibly associated with contrast mean rectal administration, unless plane X-rays has already shown “free” intra-abdominal air.

Surgery: Colonic perforation may occur as “free” perforation causing an acute, diffuse stercoral peritonitis, which is normally associated with symptoms of generalized sepsis. Such a picture needs emergency surgery by laparotomy. Obviously, the main purpose of surgery for colonic perforation is not avoiding colonic leak, since stools have already diffused in the abdomen, nor performing an oncologically complete lymphadenectomy. In the case of perforation, surgeon’s first concern is removing the cause of acute peritonitis by resecting the perforated segment and cleaning the abdomen by lavage. It should not be forgotten that obstruction by CRC may turn into acute peritonitis by perforation of proximal colon (usually the caecum) following long-term distension[156,157]. Moreover, performing an anastomosis after the resection of perforated CRC in a generalized peritonitis context carries a high risk of postoperative leakage, and deciding to perform a temporary stoma is often the preferred option. Alternatively, the anastomosis may be fashioned together with a so-called “protective”, proximal loop stoma. As this option normally implies a second surgery in order to close the stoma, it is rarely performed in a palliative setting (potential “long-survivors”).

In some cases, colonic perforation is small-sized or “covered” by other organs or perirectal fat, thus stools spilling results as being limited. In such cases, signs/symptoms of acute peritonitis may be localized, reduced or even absent, if the perforation site is deep in the abdomen or in the under-peritoneal rectum. In the absence of deteriorating septic state, perforation may be managed by conservative treatment (including antibiotics) and/or derivative procedures (stomas) rather than major resections. Perforations resulting in localized abscesses may also be managed by surgical drainage of the collection or US- or CT-scan guided procedure. Obviously, high ASA score patients or short-survivors may be supposed to benefit most by such a low mini-invasive attitude.

Although usually it is not an emergency situation, bleeding may represent a major issue of advanced CRC, especially in patients needing anticoagulant/antiaggregant therapy for any reason. Pain and tenesmus are typical symptoms of rectal tumors but are rarely treated by surgical resection, since they are usually associated to a locally infiltrating, already non resectable rectal cancer. If we consider that those symptoms are also reported to reduce under CHT[160,161], we can understand why they are usually managed conservatively by radiotherapy or transanal procedures.

Surgery: Resective surgery, obviously allows definitively treating chronic haemorrhage and other CRC -related symptoms by extirpation of tumor. The pros, cons and timing of resective surgery need to be discussed with the patient and in multidisciplinary meeting. Surgery intrinsic morbidity/mortality[27,47,59,90,91] and the possible spontaneous reduction of non-emergency symptoms owing to CRC response to CHT[55,160,161] should be balanced with the risk of performing a late, possibly emergency procedure after CHT has started, when it may carry the highest risk of complications. As reported before, resection is generally proposed for proximal tumors, whereas it is attentively pondered for rectal tumors (see above for surgical options).

Radiotherapy (RT): RT is one of the mostly adopted treatment for rectal bleeding and other invalidating symptoms. Although it is reported to relief in particular pain and bleeding in 75%-80% of patients[162,163], unfortunately, the results of studies are difficult to compare, as RT is often part of a multimodal treatment including surgery and CHT, patients are heterogeneous as well as administered RT doses, varying from 10 to 80 Gy[162,163]. Bae et al[162], analysing a series of patients with advanced symptomatic (mostly pain and bleeding) CRC undergoing various managements, including surgery, CHT and RT, found the association between CT and RT to be significantly associated to symptoms’ control[162]. The main limitations of RT is the recurrence of symptoms in roughly one half of the patients within 6 mo[59,162]; thus, it is best indicated in short survivors[59].

Laser therapy: Success rate of Nd:YAG laser (see above for general principles of endoscopic laser treatment) in managing rectal bleeding is 73%-97%[140,151,164]. Since the median symptom-free survival after the procedure(s) is 10 mo[164], its effectiveness in long-survivors is also questionable.

Transanal resection techniques: Various techniques for transanal resection have been proposed for the palliative treatment of symptomatic rectal cancer, including endoscopic transanal resection (ETAR)[156,165-167] and transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM)[159].

Performed since the early 1990s with various approaches, ETAR consists in the endorectal management of rectal tumor complications by several manoeuvres, including tumor resection/debulking and haemostasis. ETAR is reported to have a 73%-87% overall success rate in achieving symptoms relief[165,166], with a specific 50% success rate for incontinence, rectal pain and tenesmus, 66% for bleeding and 77% for diarrhoea[167]. Chen et al[156] found ETAR to be related to the same long term outcome as traditional surgery (LAR/APR) with lower morbidity (4% vs 24%), although others reported an higher 8%-17% complication rate[165,166]. Such low morbidity and a 15%-23% rate of colostomy finally performed[156,165,166] led to consider ETAR as a feasible option in palliative management of rectal cancer.

More recently introduced[168], TEM implies the full-thickness resection of the rectum including the perirectal mesorectum until reaching the recto-vaginal septum or the prostate capsule (anteriorly) or the mesorectal fascia posteriorly, followed by rectum closure. Although it is nowadays mostly reported for the management of T1-T2 rectal tumors[158,169], TEM has been also proposed for the palliative management of advanced rectal tumors[159,170]. Overrall, a 6.3%-21% morbidity is reported (mostly due to urinary retention) with a 2.3%-5% rate of severe complications requiring management[158,159,170].

Argon plasma coagulation: Initially proposed as complementary to endoscopic piecemeal resection of sessile rectal polyps in order to reduce recurrence[171], argon plasma coagulation (APC) has also a coagulative effect and has been proposed in the mid-2000s for the treatment of low entity haemorrhage[172]. The argon ionized by electrodes determines an effective but superficial fulguration of neoplastic tissue (normally less than 3 mm in depth). Also owing to the limited penetration in neoplastic tissue, complications including colonic perforation, are presumably lower than that reported after Nd:YAG laser[55].

All non-resective procedures (radiotherapy, laser therapy, APC and transanal procedures) should not be considered as excluding each other, but as multiple options to be used whenever other managements have failed.

Multifaceted therapeutic options, ranging from open surgery to minimally invasive techniques, from traditional CHT to new molecular targets, has allowed for a dramatic increase in expected survival from 4-6 mo with best supportive care to more than two years, mostly due to the introduction and diffusion of new and increasingly effective CHT agents. Differently from emergency situations which are still mostly managed surgically, the role of surgery in the palliative management of asymptomatic patients is changing following the impressive results of CHT. While the utility of asymptomatic primary CRC resection is uncertain and mostly abandoned, potentially “curative” surgery may nowadays be planned after new CHT regimens have converted irresectable liver metastasis into resectable ones.

Moreover, prolonging survival, CHT is somehow changing the perspective concerning the best long-term management of primary CRC complications, possibly challenging the role of short-lasting, mini-invasive approaches (stenting, local treatments,...). Other than survival prolongation, disease control and better quality of life are gaining importance as primary endpoints of palliative management of incurable CRC.

The so-called “small gray zone” between curable and incurable management of patients affected by CRC, has increased to “larger gray zone” through the last decades. In such a rapidly changing evolution of standards of care, oncologists, surgeons and other care-takers should be aware of the necessity of patients’ multidisciplinary discussion/management, the periodic re-evaluation of any singular case, the timely information/implication of the patient and his relatives in the treatment.

P- Reviewers: Mayol J, Wang YH S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11614] [Article Influence: 893.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8901] [Article Influence: 741.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Golan T, Urban D, Berger R, Lawrence YR. Changing prognosis of metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma: Differential improvement by age and tumor location. Cancer. 2013;119:3084-3091. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mella J, Biffin A, Radcliffe AG, Stamatakis JD, Steele RJ. Population-based audit of colorectal cancer management in two UK health regions. Colorectal Cancer Working Group, Royal College of Surgeons of England Clinical Epidemiology and Audit Unit. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1731-1736. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park JH, Kim TY, Lee KH, Han SW, Oh DY, Im SA, Kang GH, Chie EK, Ha SW, Jeong SY. The beneficial effect of palliative resection in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1425-1431. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Modlin J, Walker HS. Palliative resections in cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1949;2:767-776. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Stearns MW, Binkley GE. Palliative surgery for cancer of the rectum and colon. Cancer. 1954;7:1016-1019. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Joffe J, Gordon PH. Palliative resection for colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:355-360. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Petrelli N, Herrera L, Rustum Y, Burke P, Creaven P, Stulc J, Emrich LJ, Mittelman A. A prospective randomized trial of 5-fluorouracil versus 5-fluorouracil and high-dose leucovorin versus 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate in previously untreated patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1559-1565. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Saltz LB, Douillard JY, Pirotta N, Alakl M, Gruia G, Awad L, Elfring GL, Locker PK, Miller LL. Irinotecan plus fluorouracil/leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer: a new survival standard. Oncologist. 2001;6:81-91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, Boni C, Cortes-Funes H, Cervantes A, Freyer G. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938-2947. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D’Haens G, Pintér T, Lim R, Bodoky G. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408-1417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2901] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3021] [Article Influence: 201.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Heinemann V, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Decker T, Kiani A, Vehling-Kaiser U, Al-Batran SE, Heintges T, Lerchenmueller J, Kahl C, Seipelt G. Randomized comparison of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: German AIO study KRK-0306 (FIRE-3). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:(suppl; abstr LBA3506). [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Falcone A, Ricci S, Brunetti I, Pfanner E, Allegrini G, Barbara C, Crinò L, Benedetti G, Evangelista W, Fanchini L. Phase III trial of infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI) compared with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1670-1676. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 830] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 838] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335-2342. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7832] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7523] [Article Influence: 376.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Lorenz M, Müller HH, Schramm H, Gassel HJ, Rau HG, Ridwelski K, Hauss J, Stieger R, Jauch KW, Bechstein WO. Randomized trial of surgery versus surgery followed by adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid for liver metastases of colorectal cancer. German Cooperative on Liver Metastases (Arbeitsgruppe Lebermetastasen). Ann Surg. 1998;228:756-762. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 245] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Goéré D, Deshaies I, de Baere T, Boige V, Malka D, Dumont F, Dromain C, Ducreux M, Elias D. Prolonged survival of initially unresectable hepatic colorectal cancer patients treated with hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin followed by radical surgery of metastases. Ann Surg. 2010;251:686-691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hemming AW, Reed AI, Howard RJ, Fujita S, Hochwald SN, Caridi JG, Hawkins IF, Vauthey JN. Preoperative portal vein embolization for extended hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2003;237:686-691; discussion 691-693. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 267] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Heinrich S, Lang H. Liver metastases from colorectal cancer: technique of liver resection. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:579-584. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, Valeanu A, Castaing D, Azoulay D, Giacchetti S, Paule B, Kunstlinger F, Ghémard O. Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2004;240:644-657; discussion 657-658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 885] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lam VW, Spiro C, Laurence JM, Johnston E, Hollands MJ, Pleass HC, Richardson AJ. A systematic review of clinical response and survival outcomes of downsizing systemic chemotherapy and rescue liver surgery in patients with initially unresectable colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1292-1301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lam VW. LiverMetSurvey International Registry of Patients Operated for Colorectal Liver Metastasis. Accessed October 23, 2013. Available from: http://www.livermetsurvey.org. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Miller G, Biernacki P, Kemeny NE, Gonen M, Downey R, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, DeMatteo RP. Outcomes after resection of synchronous or metachronous hepatic and pulmonary colorectal metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:231-238. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 168] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lin BR, Chang TC, Lee YC, Lee PH, Chang KJ, Liang JT. Pulmonary resection for colorectal cancer metastases: duration between cancer onset and lung metastasis as an important prognostic factor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1026-1032. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gallinger S, Biagi JJ, Fletcher GG, Nhan C, Ruo L, McLeod RS. Liver resection for colorectal cancer metastases. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:e255-e265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Adam R, de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Aloia TA, Delvart V, Azoulay D, Bismuth H, Castaing D. Is hepatic resection justified after chemotherapy in patients with colorectal liver metastases and lymph node involvement. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3672-3680. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rosen SA, Buell JF, Yoshida A, Kazsuba S, Hurst R, Michelassi F, Millis JM, Posner MC. Initial presentation with stage IV colorectal cancer: how aggressive should we be. Arch Surg. 2000;135:530-534; discussion 534-535. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 185] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Costi R, Mazzeo A, Di Mauro D, Veronesi L, Sansebastiano G, Violi V, Roncoroni L, Sarli L. Palliative resection of colorectal cancer: does it prolong survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2567-2576. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sugarbaker PH, Gianola FJ, Speyer JC, Wesley R, Barofsky I, Meyers CE. Prospective, randomized trial of intravenous versus intraperitoneal 5-fluorouracil in patients with advanced primary colon or rectal cancer. Surgery. 1985;98:414-422. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Elias D, Gilly F, Boutitie F, Quenet F, Bereder JM, Mansvelt B, Lorimier G, Dubè P, Glehen O. Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:63-68. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 685] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 691] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Elias D, Ouellet JF, Bellon N, Pignon JP, Pocard M, Lasser P. Extrahepatic disease does not contraindicate hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2003;90:567-574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 183] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Carpizo DR, Are C, Jarnagin W, Dematteo R, Fong Y, Gönen M, Blumgart L, D’Angelica M. Liver resection for metastatic colorectal cancer in patients with concurrent extrahepatic disease: results in 127 patients treated at a single center. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2138-2146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Benson AB, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, Chen YJ, Choti MA, Cooper HS, Engstrom PF, Enzinger PC, Fakih MG, Fenton MJ. Metastatic colon cancer, version 3.2013: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:141-152; quiz 152. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Adam R, De Gramont A, Figueras J, Guthrie A, Kokudo N, Kunstlinger F, Loyer E, Poston G, Rougier P, Rubbia-Brandt L. The oncosurgery approach to managing liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Oncologist. 2012;17:1225-1239. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 367] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Floriani I, Torri V, Rulli E, Garavaglia D, Compagnoni A, Salvolini L, Giovagnoni A. Performance of imaging modalities in diagnosis of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:19-31. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 168] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | van Kessel CS, Buckens CF, van den Bosch MA, van Leeuwen MS, van Hillegersberg R, Verkooijen HM. Preoperative imaging of colorectal liver metastases after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2805-2813. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Piscaglia F, Corradi F, Mancini M, Giangregorio F, Tamberi S, Ugolini G, Cola B, Bazzocchi A, Righini R, Pini P. Real time contrast enhanced ultrasonography in detection of liver metastases from gastrointestinal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Balthazar EJ, Megibow AJ, Hulnick D, Naidich DP. Carcinoma of the colon: detection and preoperative staging by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:301-306. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 194] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rafaelsen SR, Vagn-Hansen C, Sørensen T, Pløen J, Jakobsen A. Transrectal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging measurement of extramural tumor spread in rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5021-5026. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Swartling T, Kälebo P, Derwinger K, Gustavsson B, Kurlberg G. Stage and size using magnetic resonance imaging and endosonography in neoadjuvantly-treated rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3263-3271. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Elias D, Borget I, Farron M, Dromain C, Ducreux M, Goéré D, Honoré C, Boige V, Dumont F, Malka D. Prognostic significance of visible cardiophrenic angle lymph nodes in the presence of peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancers. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1214-1218. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | de Bree E, Koops W, Kröger R, van Ruth S, Witkamp AJ, Zoetmulder FA. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal or appendiceal origin: correlation of preoperative CT with intraoperative findings and evaluation of interobserver agreement. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:64-73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 192] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |