Published online Jul 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3538

Revised: May 6, 2009

Accepted: May 13, 2009

Published online: July 28, 2009

AIM: To evaluate whether urokinase perfusion of non-heart-beating cadaveric donor livers reduces the incidence of intrahepatic ischemic-type biliary lesions (IITBLs).

METHODS: A prospective study was conducted to investigate potential microthrombosis in biliary microcirculation when non-heart-beating cadaveric livers were under warm or cold ischemic conditions. The experimental group included 140 patients who underwent liver transplantation during the period of January 2006 to December 2007, and survived for more than 1 year. The control group included 220 patients who received liver transplantation between July 1999 and December 2005 and survived for more than 1 year. In the experimental group, the arterial system of the donor liver was perfused twice with urokinase during cold perfusion and after trimming of the donor liver. The incidence of IITBLs was compared between the two groups.

RESULTS: In the control group, the incidence of IITBLs was 5.9% (13/220 cases) after 3-11 mo of transplantation. In the experimental group, two recipients (1.4%) developed IITBLs at 3 and 6 mo after transplantation, respectively. The difference in the incidence between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Double perfusion of cadaveric livers from non-heart-beating donors with urokinase may reduce the incidence of IITBLs.

- Citation: Lang R, He Q, Jin ZK, Han DD, Chen DZ. Urokinase perfusion prevents intrahepatic ischemic-type biliary lesion in donor livers. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(28): 3538-3541

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i28/3538.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3538

Intrahepatic ischemic-type biliary lesions (IITBLs) after orthotopic liver transplantation are the most frequent cause of non-anastomotic biliary strictures in liver grafts[1–4]. They affect 2%-19% of patients after liver transplantation and have become a leading cause of liver re-transplantation in China[56]. Several risk factors for IITBLs have been identified, including ischemia-related injury, immunologically induced injury, and cytotoxic injury[7–9]. Although IITBLs have a multifactorial origin, ischemia-reperfusion injury and hepatic arterial thrombosis are considered to be the major causes[10–12]. In recent years, however, impaired biliary microcirculation has led to an increasing concern. Improving microcirculation can increase oxygen supply and might prevent biliary injuries. Urokinase is a proteolytic enzyme produced by the kidney, which is found in the urine. Urokinase acts on the endogenous fibrinolytic system by converting plasminogen to plasmin, which, in return, degrades fibrin clots. Since January 2006, our center has used a procedure based on the therapeutic principle of urokinase to prevent potential microthrombosis in biliary microcirculation. We have used non-heart-beating cadaveric donor grafts in which warm or cold ischemic insult was induced and which were perfused with urokinase; this procedure has produced good results.

In the present study, we evaluated prospectively 140 liver transplantation patients who received grafts with urokinase perfusion.

This study was approved ethically by Beijing Chaoyang Hospital. All patients provided written consent. All donors were volunteers and signed consent documents before donation.

Between July 1999 and December 2005, 220 patients (176 male, 44 female; age, 14-71 years) received orthotopic liver transplantation in the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, which is affiliated to Capital Medical University (Beijing, China). All patients survived for more than 1 year. They received ABO-compatible non-heart-beating cadaveric donor livers without urokinase perfusion. The arterial system of the donor livers was perfused with 2000 mL cold histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) solution (4°C). The portal system was perfused with 2000 mL HTK solution, followed by 2000 mL University of Wisconsin (UW) solution for preservation (4°C). The biliary system was decompressed using the trocar technique. The common bile duct was perfused with normal saline at low pressure. The warm ischemia time for the donor livers was 2-8 min, and the cold preservation time was 2-13.5 h. The secondary warm ischemia for the biliary tract lasted 25-90 min. Primary diseases of the patients included posthepatitic cirrhosis in 148, primary hepatic carcinoma in 56, alcoholic cirrhosis in seven, fulminant hepatitis in four, hepatolenticular degeneration in three, and primary sclerosing cholangitis in two.

Since January 2006, all patients received donor livers with urokinase perfusion. Until December 2007, 140 patients (108 male, 32 female; age, 16-69 years) underwent liver transplantation and survived for more than 1 year. We used 2000 mL HTK solution that contained 2 MU urokinase for perfusion through the arterial system. After trimming of the donor liver, the arterial system was perfused again with 1 MU urokinase. The residual urokinase was washed out using 500 mL HTK solution before implantation. The warm ischemia time for donor livers was 2-10 min, and the cold preservation time was 2.5-15 h. The secondary warm ischemia for the biliary tract lasted 20-115 min. Primary diseases of the recipients included posthepatitic cirrhosis in 96, primary hepatic carcinoma in 34, alcoholic cirrhosis in three, fulminant hepatitis in two, hepatolenticular degeneration in two, primary sclerosing cholangitis in two, and autoimmune liver disease in one.

The immunosuppressive regimen for all the patients included cyclosporin A (CsA) (Novartis, Switzerland) or Prograf (FK506) (Astellas, Ireland), mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept; Roche, United States), and steroids. The trough CsA level was maintained at 200-300 &mgr;g/L and that of FK506 was maintained at 8-12 &mgr;g/L at 3 mo after operation. We compared the incidence of IITBLs in the patients who received grafts with or without donor urokinase perfusion.

The difference between the two groups of patients was analyzed by a χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using SPSS version 11.5 (Chicago, IL, USA).

The incidence of IITBLs was 5.9% in patients who received grafts without urokinase perfusion (13/220 patients) 3-11 mo (mean, 5.1 mo) after transplantation, and 1.4% in the patients who received grafts with urokinase perfusion (2/140 patients) at 3 and 6 mo after transplantation. The difference in the incidence between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The main symptom noted in the 15 IITBL patients in both groups was progressive hyperbilirubinemia. Cholangitis was observed as a complication in three of the 15 patients. The results of a biochemical assay showed that the level of total bilirubin increased progressively. The level of direct-reacting bilirubin increased the most, followed by the level of biliary enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyltransferase. A slight increase in the levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels was detected.

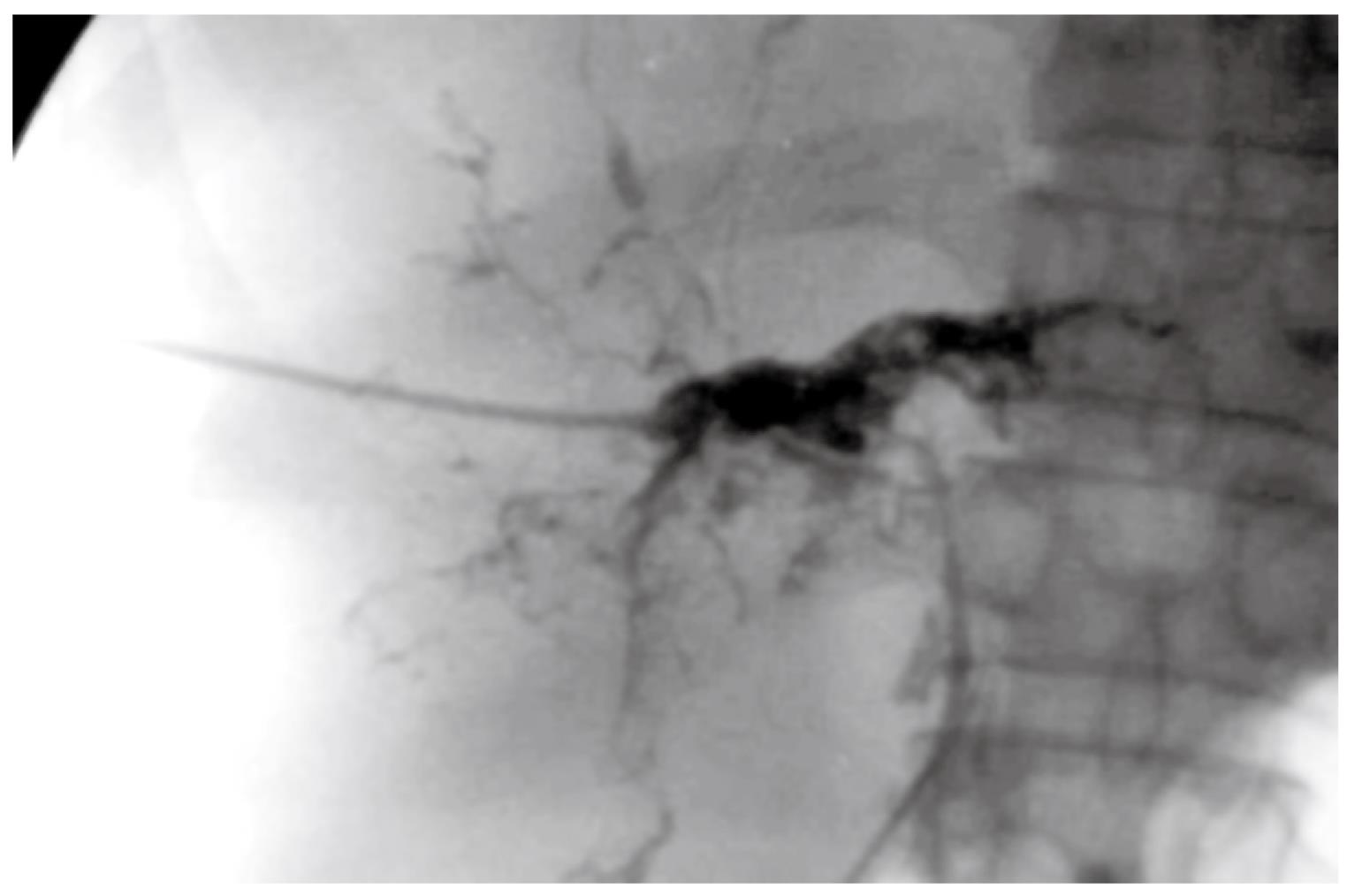

Of the 13 IITBL patients who received grafts without urokinase perfusion, four were diagnosed with IITBLs by T-tube cholangiography; two by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography; four by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; and three by magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRCP). In the two IITBL patients who received grafts with urokinase perfusion, IITBLs were diagnosed by MRCP. The imaging of the 15 IITBL patients showed varying degrees of diffuse stricture and segmental dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct, with withered-branch-like changes in the biliary tree (Figure 1). The stricture or embolic lesion of the hepatic artery and its major branches was excluded by Doppler ultrasonography, and acute or chronic rejections were excluded by liver biopsy.

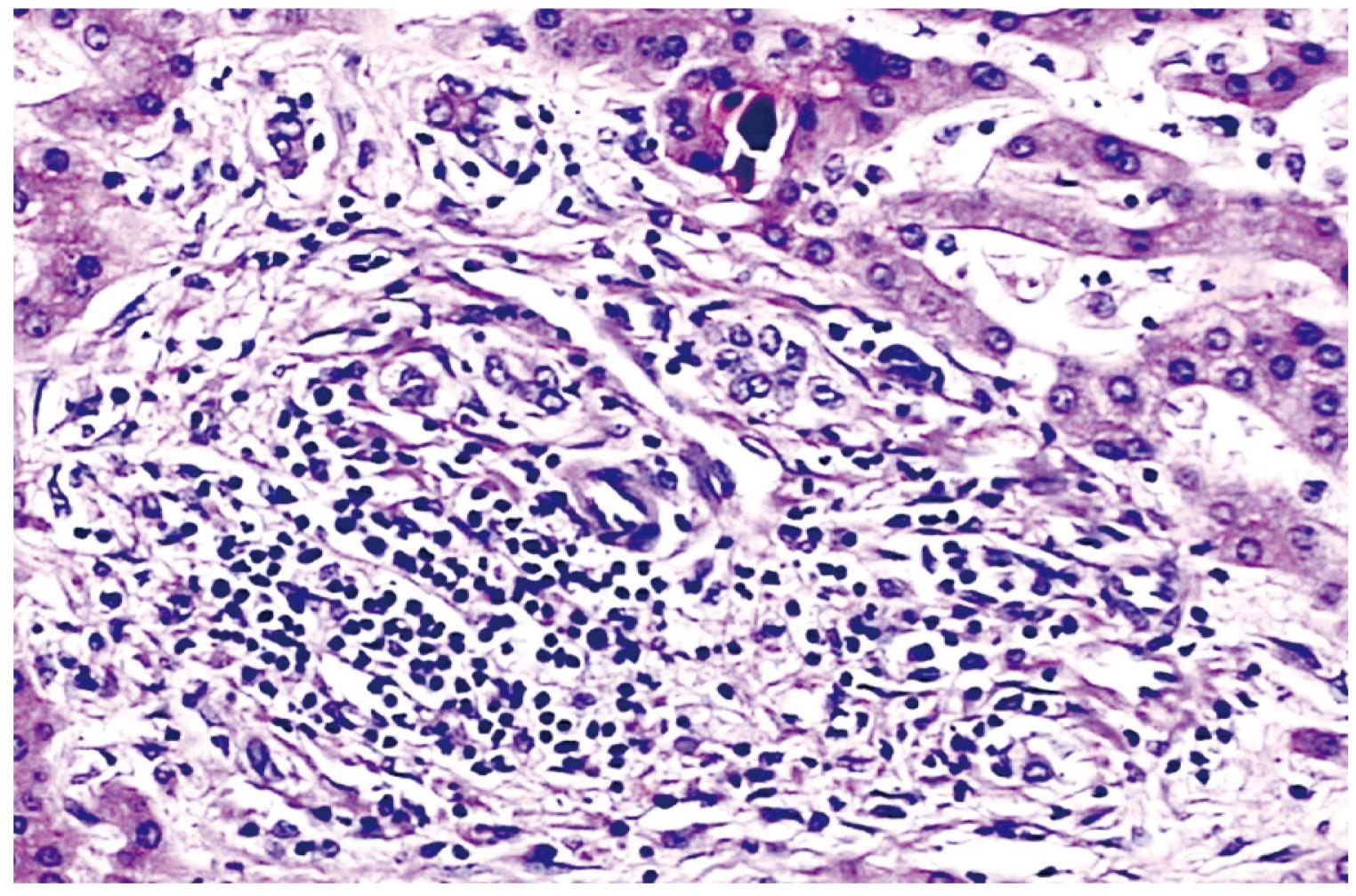

Eight of 13 IITBL patients who received grafts without urokinase perfusion required liver re-transplantation, and the other five patients died from liver failure while still on the waiting list. The two IITBL patients who received grafts with urokinase perfusion underwent liver re-transplantation. The injured grafts were removed from the 10 re-transplantation patients and observed pathologically. Gross findings showed patchy necrosis of the biliary endomembrane, thickened and sclerosed duct wall, and biliary sludge in the narrowed lumen. Microscopic findings showed severe cholestasis of hepatocytes, spotty or patchy necrosis, infiltration of inflammatory cells and mild to moderate proliferation of fibrous tissue in the portal area, necrosis and exfoliation of a great number of endothelial cells in small biliary lumens, formation of bile thrombus, and fibrosis and luminal stenosis of some bile ducts (Figure 2).

IITBLs have become a leading cause of liver re-transplantation in China[1314]. This is closely associated with the fact that non-heart-beating cadaveric livers constitute a major source of donor livers. Several studies conducted in China and other countries have suggested that cadaveric donor grafts with warm ischemic injury leads to a higher incidence of IITBLs than grafts from brain-dead donors. Abt et al[15] have reported that the ratio of IITBLs in biliary complications was 66.6% with non-heart-beating cadaveric livers and 19.2% with livers from brain-dead donors. Nakamura et al[16] have reported that the incidence of IITBLs was only 1.4% in recipients grafted with brain-dead donor livers. Zhang et al[17] have reported that in 235 patients transplanted with cadaveric livers and 36 transplanted with living-donor livers, the incidence of biliary complications was 19.1% and 5.6%, respectively. The incidence of IITBLs was 7.29% and 0%, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant. Researchers in China and other countries have agreed that the difference was mainly caused by warm ischemia.

What kinds of pathological or physiological changes associated with IITBLs may occur in a donor liver during warm ischemia? Generally, the initiation of intrinsic coagulation requires stoppage or slowing of blood flow, high blood viscosity, and injury of vascular endothelial cells. After these three requirements are met, most non-heart-beating cadaveric donors are usually in a hypercoagulable state during warm ischemia. Thus, blood coagulation or microthrombi may develop rapidly in the arterioles and peribiliary capillary plexus of the donor liver within a short period. The blood clots or microthrombi are not washed out easily by subsequent cold perfusion under normal pressure, which results in inadequate perfusion of the peribiliary capillary plexus. Even after blood circulation in the donor liver returns to normal, the arterioles and peribiliary capillary plexus still lack perfusion with arterial blood. This may lead to ischemia and hypoxia of the bile duct wall; formation of biliary sludge caused by degeneration, necrosis or even exfoliation of a great number of endothelial cells; and luminal stenosis caused by gradual fibrosis of the muscular layers. By periodically sampling livers from rats dying suddenly from cardiac arrest for light microscopy, we observed blood coagulation in most arterioles in the portal area in hepatic tissue samples collected after 25 min of cardiac arrest. For the reasons described above, we adopted the strategy of double perfusion with urokinase, which aimed to achieve maximum dissolution of microthrombi, ensure better effects of cold perfusion and reperfusion, and prevent the development of IITBLs. In the present study, we found that the difference between the two groups was significant, which indicated that urokinase perfusion can effectively reduce the incidence of IITBLs.

The in vitro use of urokinase may not have any effect on the coagulation function of patients and is not dose-limited. Thus, urokinase usually can be administered in vitro at a higher concentration than when injected intravenously. For better blood circulation in arterioles and the peribiliary capillary plexus, a higher concentration of urokinase could be used to reperfuse the liver after trimming. A urokinase-free preservation solution should be used to perfuse the artery to wash out excess urokinase before completing the whole perfusion process. The activity and function of urokinase at 0-4°C have not been reported yet. In separate tests, a significant thrombolytic effect was observed when fresh blood clots in tubes at 4°C were immersed in urokinase at the above-mentioned concentrations.

The results of the present study confirm that: (1) liver transplantation from non-heart-beating cadaveric donors may lead to a higher incidence of IITBLs and a higher rate of re-transplantation; and (2) double perfusion of cadaveric livers from non-heart-beating donors with urokinase may reduce the incidence of IITBLs.

Biliary complications are a major cause of morbidity and graft failure in patients after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). The most troublesome is the so-called intrahepatic ischemic-type biliary lesion (IITBL), which is one of the most important reasons for liver re-transplantation. Therefore, it is clinical significance to reduce the incidence of IITBLs in order to decrease the re-transplantation rate and improve long-term life quality.

The incidence of IITBL varies between 2% and 19% after OLT. Although the exact pathophysiological mechanism of IITBL is still unknown, several risk factors of this often cumbersome complication have been identified, strongly suggesting a multi-factorial origin. Therefore, the etiology, development and prophylaxis of IITBL have been hot topics of research.

Improving biliary microcirculation might prevent biliary injury. In this study, urokinase was perfused through the arterial system during harvesting and after trimming of donor liver in non-heart-beating cadaveric donors. This procedure has produced good results and provides the possibility of reducing IITBLs after OLT.

This study may provide a method for clinical research into the prophylaxis of IITBLs after liver transplantation. This technique for prevention of IITBLs is easy to establish, and the results of this study confirm that urokinase perfusion may reduce the incidence of IITBLs from non-heart-beating cadaveric donors.

ITBL is defined as non-anastomotic destruction of the graft’s biliary tree after OLT, and is characterized by bile duct destruction, subsequent stricture formation, and sequestration.

This is a good descriptive study in which the authors analyze the preventive effect of urokinase perfusion on IITBLs in non-heart-beating donors after OLT. The results are interesting and the conclusion is encouraging.

| 1. | Park JS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Lee SS, Han J, Min YI, Hwang S, Park KM, Lee YJ. Efficacy of endoscopic and percutaneous treatments for biliary complications after cadaveric and living donor liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:78-85. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Rerknimitr R, Sherman S, Fogel EL, Kalayci C, Lumeng L, Chalasani N, Kwo P, Lehman GA. Biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with choledochocholedochostomy anastomosis: endoscopic findings and results of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:224-231. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Jagannath S, Kalloo AN. Biliary Complications After Liver Transplantation. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2002;5:101-112. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Patkowski W, Nyckowski P, Zieniewicz K, Pawlak J, Michalowicz B, Kotulski M, Smoter P, Grodzicki M, Skwarek A, Ziolkowski J. Biliary tract complications following liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:2316-2317. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Abou-Rebyeh H, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Radke C, Steinmuller T, Wiedenmann B, Hintze RE. Complete bile duct sequestration after liver transplantation, caused by ischemic-type biliary lesions. Endoscopy. 2003;35:616-620. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Buis CI, Hoekstra H, Verdonk RC, Porte RJ. Causes and consequences of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:517-524. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Busuttil RW. Ischemia and reperfusion injury in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1653-1656. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Moench C, Moench K, Lohse AW, Thies J, Otto G. Prevention of ischemic-type biliary lesions by arterial back-table pressure perfusion. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:285-289. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Rull R, Garcia Valdecasas JC, Grande L, Fuster J, Lacy AM, Gonzalez FX, Rimola A, Navasa M, Iglesias C, Visa J. Intrahepatic biliary lesions after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2001;14:129-134. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Guichelaar MM, Benson JT, Malinchoc M, Krom RA, Wiesner RH, Charlton MR. Risk factors for and clinical course of non-anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:885-890. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Cameron AM, Busuttil RW. Ischemic cholangiopathy after liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:495-501. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Pascher A, Neuhaus P. Bile duct complications after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2005;18:627-642. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Zhu ZJ, Rao W, Sun JS, Cai JZ, Deng YL, Zheng H, Zhang YM, Jiang WT, Zhang JJ, Gao W. Liver retransplantation for ischemic-type biliary lesions after orthotopic liver transplantation: a clinical report of 66 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:471-475. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Cai CJ, Yi SH, Li MR, Wang GS, Yang Y, Lu MQ. Characteristics of patients undergoing liver re-transplantation during perioperative period and the management. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2008;28:44-46. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Abt P, Crawford M, Desai N, Markmann J, Olthoff K, Shaked A. Liver transplantation from controlled non-heart-beating donors: an increased incidence of biliary complications. Transplantation. 2003;75:1659-1663. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Nakamura N, Nishida S, Neff GR, Vaidya A, Levi DM, Kato T, Ruiz P, Tzakis AG, Madariaga JR. Intrahepatic biliary strictures without hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation: an analysis of 1,113 liver transplantations at a single center. Transplantation. 2005;79:427-432. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Zhang F, Wang XH, Li XC, Xia YX. Etiological analysis of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Zhonghua Gandan Waike Zazhi. 2006;12:237-239. [Cited in This Article: ] |