Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4527

Peer-review started: May 14, 2020

First decision: June 7, 2020

Revised: June 18, 2020

Accepted: August 29, 2020

Article in press: August 29, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome is a rare autoinflammatory disease for which clinical treatment has not been standardized. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors represent a novel therapeutic option for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and some other autoinflammatory diseases. However, the clinical utility of JAK inhibitors in treating SAPHO syndrome has not been thoroughly investigated. In this study, we describe a patient with SAPHO syndrome who failed to respond to conventional treatment but demonstrated a remarkable and rapid response to the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib.

A 62-year-old female patient presented with swelling and pain at the sternoclavicular joints, back pain that limited her activities, arthralgia in the right knee, and cutaneous lesions. Her symptoms were unresponsive to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, Tripterygium wilfordii hook f, and bisphosphonates. SAPHO syndrome was diagnosed in accordance with dermatological and osteoarticular manifestations and abnormal inflammatory factors. Multiple image studies have illustrated bone lesions and pathological fractures of vertebral bodies. Oral treatment with tofacitinib at 5 mg twice daily with methotrexate and bisphosphonates was initiated. The patient reported that her pain symptoms were relieved after 3 d and her cutaneous lesions were reduced after 4 wk of treatment. Vertebral lesions were improved after 6 mo on tofacitinib. No serious adverse effects were noted.

JAK inhibitor therapy may be a promising strategy to treat SAPHO syndrome.

Core Tip: Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome is a rare autoinflammatory disease for which clinical treatment has not been standardized. We describe a patient with SAPHO syndrome who failed to respond to conventional treatment but demonstrated a remarkable and rapid response to the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib. This case highlights that Janus kinase inhibitor therapy may be a promising strategy to treat SAPHO syndrome.

- Citation: Li B, Li GW, Xue L, Chen YY. Rapid remission of refractory synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome in response to the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4527-4534

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4527.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4527

Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome, a rare disease with an estimated prevalence of 0.00144/100000[1], is characterized by a constellation of clinical features including dermatological disorders and inflammatory osteoarticular lesions. It was named by Chamot et al[2] in 1987[3]. However, there is no evidence-based treatment recommendation for SAPHO. Current goals of treatment are to relieve clinical symptoms, control inflammation, and enhance the quality of wellbeing of the patient.

This report describes a patient with SAPHO syndrome who presented with palmoplantar pustules, swelling and pain at the sternoclavicular joints, back pain, and arthralgia in the right knee. These clinical features failed to respond to conventional treatment, but remitted after use of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib.

A 62-year-old female patient presented to the Rheumatology Department of our hospital complaining of Swelling and tenderness in the right knee, severe tenderness in the lower back, and cutaneous lesions.

The patient presented with lower back and left side hip pain and palmoplantar pustules in March 2014. Blood analysis showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 89 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) at 8.78 mg/L (reference range, 0-10.00mg/L). Complete blood count and measures of liver and renal function were all within the normal range. Rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, human leukocyte antigen B27, and antinuclear antibodies were all negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of her lumbar spine demonstrated multiple vertebral lesions (L1 and L2 vertebral bodies and surrounding soft tissue). With empirical administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the above symptoms were partially relieved. Swelling and pain at the sternoclavicular joints was completely relieved after using NSAIDs.

Swelling and tenderness in the right knee was evident and more severe tenderness with limited movement arose in the lower back in August 2018. The patient was diagnosed with SAPHO syndrome. She had been suffering from recurrent pustules on the palms of her hands and lateral of her crus for 5 years prior to admission. There was no history of similar symptoms in her family.

At age 30, she was diagnosed with viral encephalitis, with sequelae including speech difficulties and paroxysmal hand tremors. She also had a history of hypertension for the past 5 years.

The patient’s temperature was 36.8 °C, heart rate was 80 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per min, blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 99%. Swelling and tenderness was evident in the right knee and tenderness with limited movement in the lower back. A pustule-like rash was found on the palm and flank of both legs.

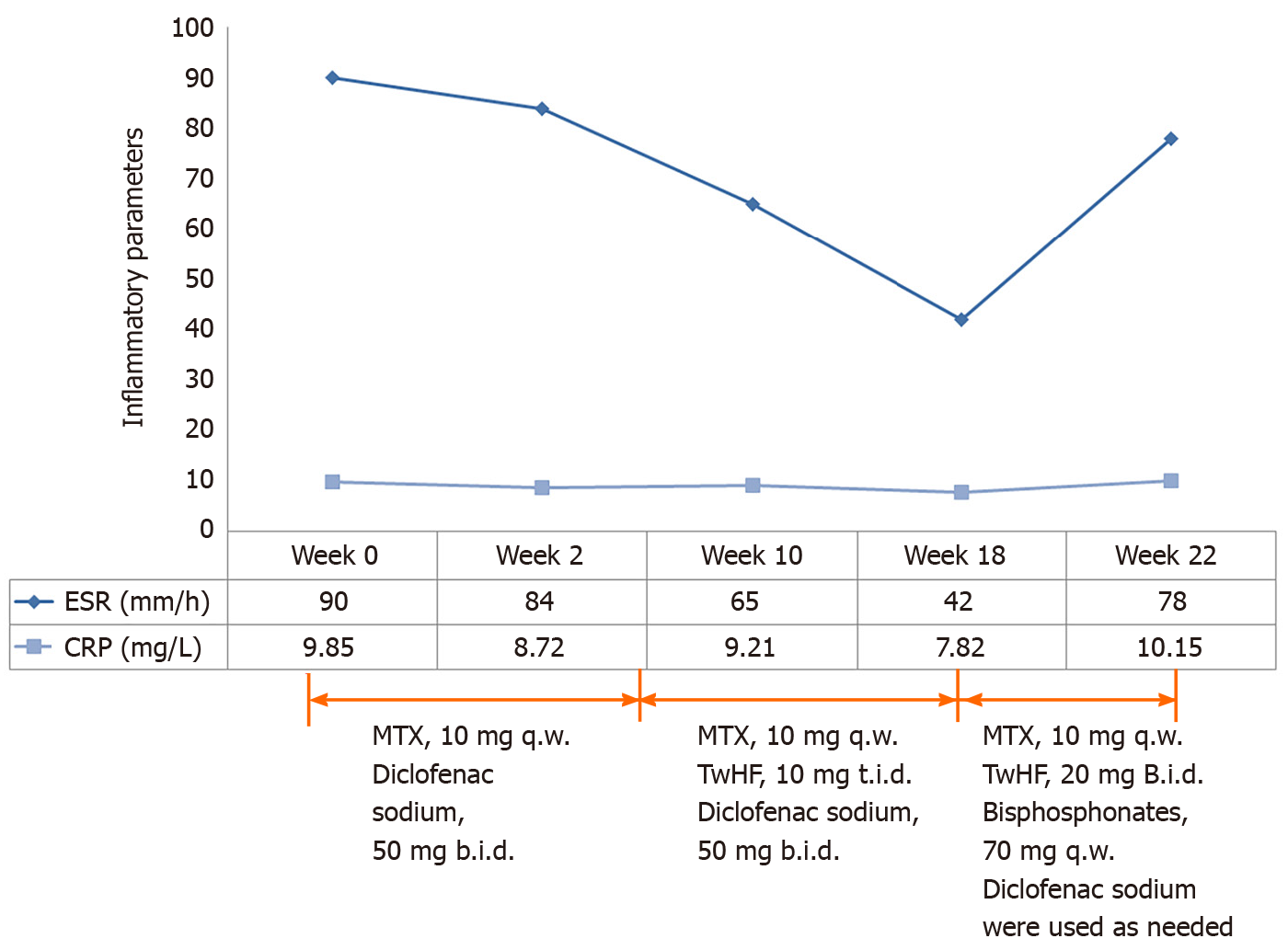

Blood analysis showed an ESR of 90 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), CRP at 9.85 mg/L (reference range, 0–10.00 mg/L), complement C3 at 1.26 g/L (reference range, 0.79-1.52 g/L), complement C4 at 0.37 g/L (reference range, 0.16-0.38 g/L), and immunoglobulin G at 17.30 g/L (reference range, 7.51-15.60 g/L). A complete blood count, electrolytes, and liver and renal function were all within the normal range. Rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, human leukocyte antigen B27, antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen and anti-double stranded DNA antibodies were all negative. Serum proinflammatory cytokine levels were significantly elevated: Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) 16.9 pg/mL (reference range, ≤ 8.1 pg/mL), interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β) 6.4 pg/mL (reference range, < 5 pg/mL), IL-6 2.98 pg/mL (reference range, ≤ 3.4 pg/mL), IL-8 32.0 pg/mL (reference range, < 62 pg/mL), and IL-10 < 5.0 pg/mL (reference range, ≤ 9.1 pg/mL). In addition, there was vitamin D deficiency, β-collagen degradation products, and bone-derived alkaline phosphatase redundancy. Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative. No evidence of tumor or tuberculosis was found.

Sternoclavicular joints lesions and sacroiliac joints with bone hyperplasia were revealed by computerized tomography (Figure 1A and B). MRI obtained on various segments of the spine indicated end plate inflammation at the C6/7 and abnormal signal intensity at C5, T2 and T3, which suggested bone marrow edema (Figure 1D-G). MRI scans of the thoracic and lumbar spine demonstrated multiple vertebral lesions and pathological fractures (T10 and L1 vertebral bodies), and end plate inflammation at T10/11, T12/L1 and L5/S1 (Figure 1H-J).

A diagnosis of SAPHO syndrome was made, in accordance with the diagnostic criteria proposed in 2012[4].

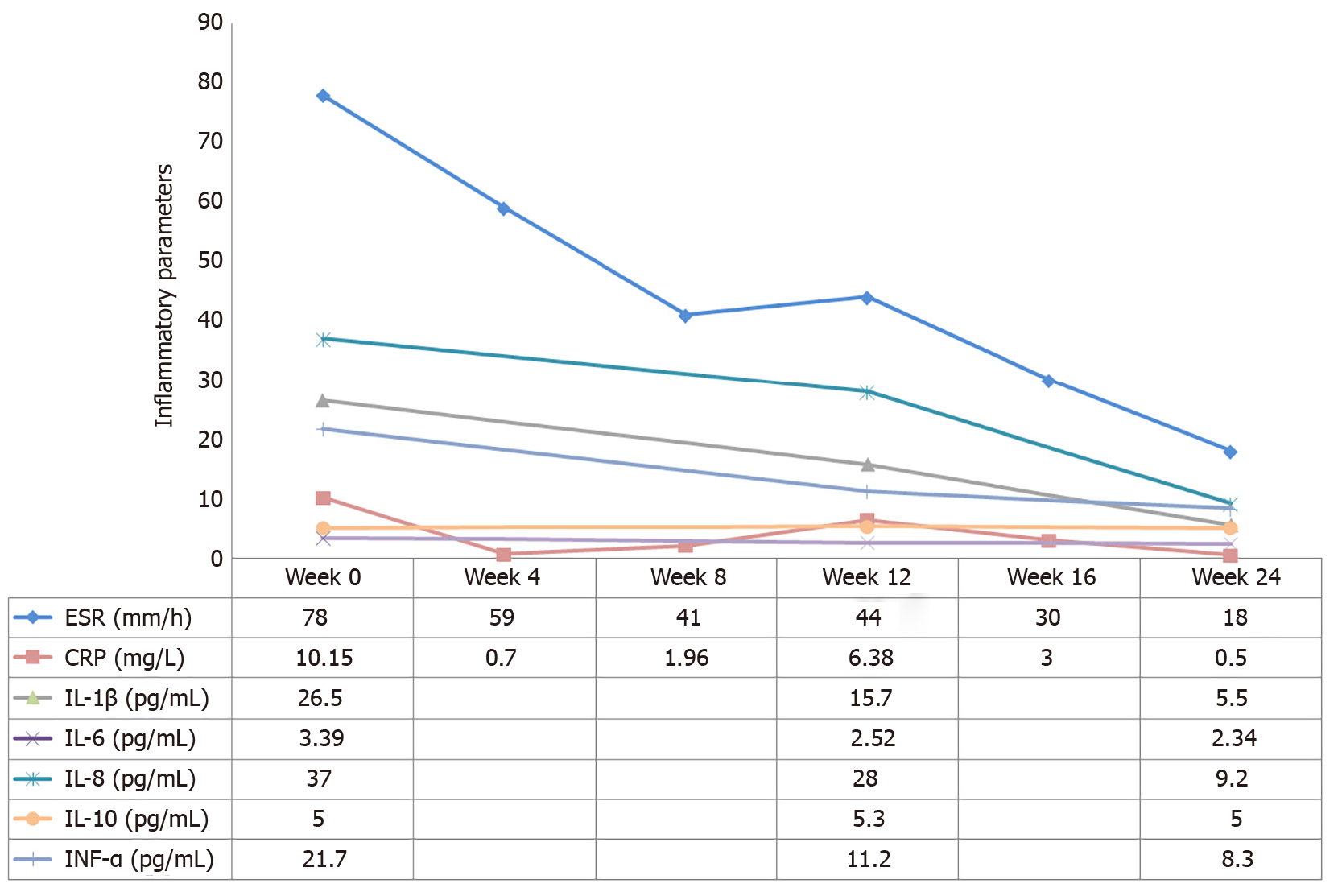

Treatment with NSAIDs and methotrexate (MTX) (10 mg/wk) was initiated. Pain in the right knee and lower back remitted. Swelling and tenderness in the left elbow appeared 1 mo later. Therefore, tripterygium wilfordii hook f (TwHF) (10 mg 3 times/d) was initiated together with NSAIDs and MTX. After 3 mo, all symptoms were improved and ESR was reduced to 42 mm/h. Treatment with MTX (10 mg/wk) and TwHF (20 mg 2 times/d) with bisphosphonates was initiated. Unfortunately, symptoms in the left elbow recurred 1 mo later, and pain in the left side of the waist at night was aggravated. Meanwhile, serum ESR and CRP levels increased to 78 mm/h and 10.15 mg/L, respectively (Figures 2 and 3). Serum proinflammatory cytokine levels were significantly increased: TNF-α 21.7 pg/mL, IL-1β 26.5 pg/mL, IL-6 3.39 pg/mL, IL-8 37.0 pg/mL, and IL-10 5.0 pg/mL (Figure 3). Note that the palmoplantar pustules recurred throughout the course of the disease. It should be mentioned that during the course of the disease, the patient also took leflunomide for 3 d, and then stopped due to a significant increase in blood pressure.

Tofacitinib, a small-molecule inhibitor of JAKs, was administered at 5 mg twice daily together with MTX (10 mg/wk) and bisphosphonates.

After 3 d of using tofacitinib, the patient reported that the pain was remarkably relieved and the palmoplantar pustules healed after 4 wk. ESR, CRP, IL-1β and TNF-α levels decreased to normal or near-normal ranges after 6 mo on tofacitinib (Figure 3). Bone marrow edema on T10 and L1 vertebral bodies disappeared, no pathological fractures were found, and end-plate inflammation improved (Figure 1K and L). Bone hypertrophy of the sternoclavicular joint was not improved (Figure 1C). The patient developed an upper respiratory infection at week 12 which improved after 3 d of self-medication. No other adverse effects including anemia, leukopenia, liver function impairment, or kidney function impairment were noted. The patient was very satisfied with the treatment.

SAPHO syndrome is an auto-inflammatory disease with significant cutaneous and musculoskeletal inflammation. The etiology is unknown and may be related to genetic, infective and immune factors.

The diagnostic criteria have been revised three times. The original diagnostic criteria in 1994 emphasized aseptic inflammation of bone and joint with characteristic skin manifestations, but it was important to note the pathologic and pathological evidence of the disease. However, subsequent studies have proved that the prognosis of SAPHO syndrome is relatively good, so invasive operations are no longer recommended. The following revisions were made at the ACR annual meeting in 2003, which emphasize that SAPHO can be diagnosed as long as characteristic rashes (palmar plantar pustules and severe acne) are accompanied by joint symptoms. Bone biopsy or imaging evaluation were performed only in patients without rash. However, the revised criteria required the exclusion of infectious osteomyelitis, bone tumors, and non-inflammatory densification changes. As of 2012, the criteria emphasized the imaging approaches. SAPHO can be diagnosed with evidence of bone hypertrophy in the anterior chest wall, extremities, and spine, as well as a characteristic rash. Invasive examination is no longer recommended and clinical symptoms such as the typical rash and characteristic imaging features are emphasized in diagnosis.

SAPHO has following clinical characteristics: A characteristic skin rash, predominantly axial bone involvement, especially the sternoclavicular joint, followed by the spine and sacroiliac joint. Some patients have peripheral joint involvement. Inflammatory indicators and bone destruction indicators are elevated, and imaging evidence of bone hypertrophy and disc inflammation can be found. The course of SAPHO is prolonged and recurring. The first subacute attack may be completely cured, and the disability rate is low. The patient followed in this study demonstrated most of the clinical manifestations described above, and the diagnosis of SAPHO was clear after exclusion of infection, tuberculosis, tumor and other diseases.

Due to its rarity, treatment has not been standardized and is mostly based on case reports, case series, expert judgment, and learning from RA, psoriatic arthritis, for the purpose of controlling the pain and the inflammatory process. In general, NSAIDs and analgesics can be regarded as first-line treatments for pain relief[5]. Short-term use of glucocorticoids may be necessary. Some reports have shown that disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are beneficial to patients and can be used chronically[6]. However, the efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on skin and joint symptoms remains controversial. Antibiotics are effective in some patients, especially those with skin lesions[7]. Bisphosphonates have been used as a third-line treatment for SAPHO syndrome due to their ability to inhibit bone resorption and relieve joint symptoms[8]. As a result, we started patient treatment with methotrexate and diclofenac, gradually adding TwHF and bisphosphonates. Unfortunately, the patient did not respond well to these drugs, particularly the skin rashes. The pathogenesis of SAPHO syndrome remains unclear, however several similarities to auto-inflammatory diseases have been found. Genetic studies have associated SAPHO syndrome with mutations in lipin 2, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2, and proline-serine-threonine phosphatase-interacting protein 1[8]. As has been demonstrated in some studies, propionibacterium acne can be found in joint fluid and bone biopsy specimens of SAPHO patients, which may contribute to the onset of disease by causing abnormal activation of innate immunity and cellular immunity. The levels of IL-1, IL-8, IL-17, IL-18, and Th17 in the peripheral blood of SAPHO patients are increased[5,9,10]. The expression of TNF-α in peripheral blood and bone tissue is increased, and the level of IL-10 in peripheral blood is decreased, leading to auto-inflammation[11]. Immune cells are activated by numerous cytokines to produce more cytokines through different pathways, which can make the inflammatory response a cascade of amplification.

In recent years targeted therapies against biological agents such as TNF-α[12], anti-IL-1[13] and IL-23 or IL-17[14] have proved to be effective treatments for the majority of patients with refractory SAPHO[5]. However, drug hypersensitivity, treatment failure or paradoxical effects of these inhibitors are frequently observed in clinical practice[15,16]. Despite the lack of systematic evidence and practical guidelines, many studies have shown that simultaneous use of DMARD, particularly MTX, has improved efficacy and reduced secondary failure of biotherapy due to anti-drug antibodies. Therefore, considering the increase of TNF-α and IL-1 levels suggested in the auxiliary examination, we recommended biological agents to the patient. However, in consideration of the severe allergy to previous drug injections such as penicillin, the patient refused the use of biological agents.

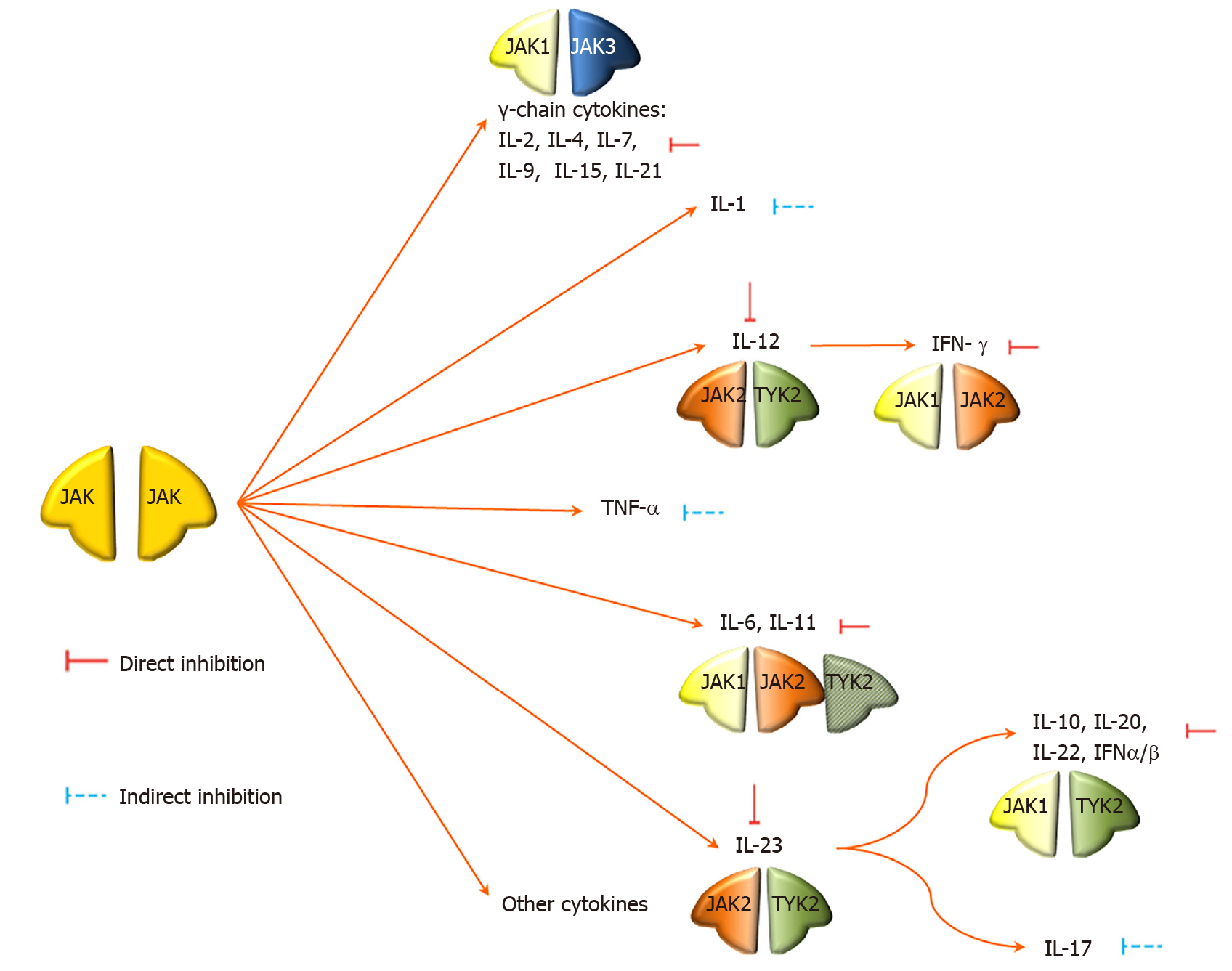

Common biological agents exert an inhibitory effect outside the cell and target single cytokines. JAKs are important intracellular signaling mediators, transmitting signals from receptors for cytokines, interleukins, interferons and colony-stimulating factors to signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) by phosphorylation. Then phosphorylated STAT translocates into the nucleus to activate gene transcription. The JAK family consists of four members: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. Different cytokines signal through different JAK combinations; blocking the JAKs can block the action of a number of cytokines directly or indirectly, including γ-chain cytokines, IL-1, IL-6, IL-7, IL-12, IL-15, IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, and TNF-α (Figure 4). As a result, JAK inhibitors are emerging therapies that are demonstrating efficacy for the treatment of inflammatory diseases that act through cytokine production[17-21].

Recently, JAK inhibitors showed great efficacy in the treatment of RA in the phase III clinical trial of the global ORAL series[22], and of psoriatic arthritis in the clinical trial of the OPAL series[23-25]. Inspired by the treatment guidelines for RA[26], treatment with tofacitinib, a small-molecule inhibitor of JAKs, was undertaken in the present study. The patient was informed of the possible adverse effects of using JAK inhibitors, such as increased risk of infection, anemia, leucopenia, cancer and cardiovascular disease[22]. Although adverse reactions did not arise in this patient, biological indicator measures and precautions should be taken when using JAK inhibitors, based on their biological functions.

To the best of our knowledge, SAPHO is rare and easily misdiagnosed. Typical rashes and imaging features are helpful in diagnosis. Traditional DMARDs use is effective to half of the patients, and TNF-α antagonists and IL-1 antagonists have been shown to be effective against refractory SAPHO. The JAK inhibitor Tofacitinib has been shown to be effective in patients with poor response to traditional agents and those unable to tolerate traditional drugs or biological agents; Tofacitinib has a rapid onset, good efficacy and few adverse effects.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tabibian JH S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Mochizuki Y, Omura K, Hirai H, Kugimoto T, Osako T, Taguchi T. Chronic mandibular osteomyelitis with suspected underlying synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome: a case report. J Inflamm Res. 2012;5:29-35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Chamot AM, Benhamou CL, Kahn MF, Beraneck L, Kaplan G, Prost A. [Acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteitis syndrome. Results of a national survey. 85 cases]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1987;54:187-196. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Rukavina I. SAPHO syndrome: a review. J Child Orthop. 2015;9:19-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Nguyen MT, Borchers A, Selmi C, Naguwa SM, Cheema G, Gershwin ME. The SAPHO syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:254-265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Firinu D, Garcia-Larsen V, Manconi PE, Del Giacco SR. SAPHO Syndrome: Current Developments and Approaches to Clinical Treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18:35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Akçaboy M, Bakkaloğlu-Ezgü SA, Büyükkaragöz B, Isıyel E, Kandur Y, Hasanoğlu E, Buyan N. Successful treatment of a childhood synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome with subcutaneous methotrexate: A case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2017;59:184-188. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Colina M, Trotta F. Antibiotics may be useful in the treatment of SAPHO syndrome. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:697-698. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Adamo S, Nilsson J, Krebs A, Steiner U, Cozzio A, French LE, Kolios AGA. Successful treatment of SAPHO syndrome with apremilast. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:959-962. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Przepiera-Będzak H, Fischer K, Brzosko M. Serum Interleukin-18, Fetuin-A, Soluble Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1, and Endothelin-1 in Ankylosing Spondylitis, Psoriatic Arthritis, and SAPHO Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Przepiera-Będzak H, Fischer K, Brzosko M. Extra-Articular Symptoms in Constellation with Selected Serum Cytokines and Disease Activity in Spondyloarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:7617954. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, Nam J, Ramiro S, Voshaar M, van Vollenhoven R, Aletaha D, Aringer M, Boers M, Buckley CD, Buttgereit F, Bykerk V, Cardiel M, Combe B, Cutolo M, van Eijk-Hustings Y, Emery P, Finckh A, Gabay C, Gomez-Reino J, Gossec L, Gottenberg JE, Hazes JMW, Huizinga T, Jani M, Karateev D, Kouloumas M, Kvien T, Li Z, Mariette X, McInnes I, Mysler E, Nash P, Pavelka K, Poór G, Richez C, van Riel P, Rubbert-Roth A, Saag K, da Silva J, Stamm T, Takeuchi T, Westhovens R, de Wit M, van der Heijde D. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:960-977. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Crowley EL, O'Toole A, Gooderham MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa with SAPHO syndrome maintained effectively with adalimumab, methotrexate, and intralesional corticosteroid injections. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2018;6:2050313X18778723. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Wendling D, Prati C, Aubin F. Anakinra treatment of SAPHO syndrome: short-term results of an open study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1098-1100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Wendling D, Aubin F, Verhoeven F, Prati C. IL-23/Th17 targeted therapies in SAPHO syndrome. A case series. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:733-735. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Sun XC, Liu S, Li C, Zhang S, Wang M, Shi XH, Hao WX, Zhang W. Failure of tocilizumab in treating two patients with refractory SAPHO syndrome: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2018;46:5309-5315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Li C, Wu X, Cao Y, Zeng Y, Zhang W, Zhang S, Liu Y, Jin H, Zhang W, Li L. Paradoxical skin lesions induced by anti-TNF-α agents in SAPHO syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:53-61. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Brandstetter B, Dalwigk K, Platzer A, Niederreiter B, Kartnig F, Fischer A, Vladimer GI, Byrne RA, Sevelda F, Holinka J, Pap T, Steiner G, Superti-Furga G, Smolen JS, Kiener HP, Karonitsch T. FOXO3 is involved in the tumor necrosis factor-driven inflammatory response in fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Lab Invest. 2019;99:648-658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Ghoreschi K, Jesson MI, Li X, Lee JL, Ghosh S, Alsup JW, Warner JD, Tanaka M, Steward-Tharp SM, Gadina M, Thomas CJ, Minnerly JC, Storer CE, LaBranche TP, Radi ZA, Dowty ME, Head RD, Meyer DM, Kishore N, O'Shea JJ. Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550). J Immunol. 2011;186:4234-4243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | O'Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, Gadina M, McInnes IB, Laurence A. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311-328. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Ghoreschi K, Gadina M. Jakpot! New small molecules in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:7-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Villarino AV, Kanno Y, O'Shea JJ. Mechanisms and consequences of Jak-STAT signaling in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:374-384. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Schwartz DM, Kanno Y, Villarino A, Ward M, Gadina M, O'Shea JJ. JAK inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for immune and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;17:78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, Behrens F, Blanco R, Kaszuba A, Kudlacz E, Wang C, Menon S, Hendrikx T, Kanik KS. Tofacitinib for Psoriatic Arthritis in Patients with an Inadequate Response to TNF Inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1525-1536. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Colbert RA, Ward MM. JAK Inhibitors Taking on Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1582-1584. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Wang TS, Tsai TF. Tofacitinib in psoriatic arthritis. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:1153-1163. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Burmester G, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux-Viala C, Gossec L, Nam J, Ramiro S, Winthrop K, de Wit M, Aletaha D, Betteridge N, Bijlsma JW, Boers M, Buttgereit F, Combe B, Cutolo M, Damjanov N, Hazes JM, Kouloumas M, Kvien TK, Mariette X, Pavelka K, van Riel PL, Rubbert-Roth A, Scholte-Voshaar M, Scott DL, Sokka-Isler T, Wong JB, van der Heijde D. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492-509. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |