INTRODUCTION

Mental and physical health in chronic disease

Influencing mental and physical health outcomes to live a long and prosperous life has been a human goal from time immemorial. Nevertheless, current health care systems deal with an increasing number of patients with chronic mental diseases. Patients with chronic conditions are at serious risk of developing multi-morbidities. Thus, interdisciplinary communication remains challenging. Providers so far poorly address management of co- and multi-morbidity, including decreased health-related quality of life together with high costs. Multi-morbid patients use health care services more often, and a bad socio-economic situation is associated with an amplified utilization of services[1]. Meanwhile, there is a tendency to expand economic rationality to moral, social, and cultural spheres. This tendency demands rational and market-oriented subjects, creating tension and possibly self-instrumentation[2].

Driven by a desire to live, humans engage with the environment, and in fighting for one’s cause the aim is to reach individual fulfillment when contextual factors allow it. In psychoanalytic theorizing, human personality is complex. While different unconscious impulses thrive to wish fulfillment and manifestation, the human psyche deals with conflicting impulses and the demands posed by the social environment and reality the individual is confronted with. The sense of agency is often compromised in chronic conditions, leading to dysfunctional beliefs and perpetuating behavior patterns, worsening the chronic disease (e.g., sedentary lifestyle in obesity, non-adherence to medication). In the disease’s course, significant parts of the patients’ lives are perceived as being dominated by the disease. Social withdrawal due to low (mental) health, resulting in less support and loneliness, is a vicious circle again feeding maladaptive cognition[3]. Integration of mental health care with physical care could reduce associated morbidity and mortality[4].

Comorbid mental disorders significantly lower quality of life when confronting “medically ill” persons with and without a mental illness[5]. Dysregulation of circadian rhythms could influence biology, behavior, and health[6,7] and vice versa thus explaining some of the associations between lifestyle and the other factors.

Existing psychiatric diagnostical systems, like provided through the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM), focus on intrapersonal features and symptoms leading to or caused by disease provide a standardized language for conceptualizing a clinical case and for research. However, by focusing on intrapersonal factors, they so far do not do justice to an individual’s contexts or interpersonal factors contributing to onset, course, and outcome of diseases. The revision of criteria in DSM-5 shows the trend to a dimensional approach and to include interpersonal factors[8]. Psychoanalysis on the other hand, besides its main aim to provide access to unconscious conflicts and motives, has a focus on relational problems and abilities arising from complicated relations in childhood. With its promising outcomes and an emphasis on a self-determined life for the individual, it could provide an approach to more individualized patient care. This is especially true when it comes to establishing a good enough patient-therapist relationship and thus creating the foundation for adherence to interventions and outcomes.

Example

When first referred to psychiatry, the patient was 20-years-old. At the time when she presented herself to our clinic, she was 41-years-old and had been suffering from persisting lower back pain, without an apparent biological explanation (ICD-10: F45.4), and from moderate bulimia (DSM IV 307.51, ICD-10: F.50.2)[9]. The patient at that time did not take any medication but frequently used various medical and social services due to her somatic symptoms. However, most recently she had considered psychotherapy as an option.

Her mother had died when the patient was 15-years-old. She felt besetting exhaustion reaching back to those times when she complained about her stolen childhood. The contact with her father had been discontinued due to child abuse. Feelings of guilt and shame so far had prevented her from talking about it. The patient had engaged in self-harming behavior, including suicide attempts. She had taken early retirement from her job as a medical technical assistant. “There is no going back to work. No! I do not go back to work. No, I don’t go back to work, for sure.” The patient wanted to change apartments but informing her cohabitant about that overwhelmed her. Repeated outbursts of anger during the session with her, all of a sudden shouting at the therapist, alternated with episodes of silence, with her refusing to answer the therapist’s questions at all. Confronted with her intimidating acting and behavior, she burst into laughter and at first could not acknowledge what consequences her behavior might have had and not the inadequacy of it.

Confronted with the confusion in the therapist and with the lack of reasonable explanations for her at random not answering questions, she mentioned the child abuse for the first time in the encounter with this therapist. However, after a thoughtful exploration, the therapist could not identify any paranoid ideas, hallucinations, or anxiety in the patient, possibly explaining her behavior. Confronted with her knowing that her outbursts might intimidate others, she laughed again but denied a possible pleasing effect of this reaction. With a sigh, she negated any intent behind her actions and justified it with the need of defending herself if the therapist would insist on asking “stupid” questions. Nevertheless, the therapist faced her with her knowing about the feelings she provoked in him and her continuing to do so, even now. Consequently, the patient remained speechless and stumbled, explaining that all that she had wanted was help. The psychotherapist and psychiatrist diagnosed a borderline personality disorder (BPD) based on a semi-structured interview.

DISCUSSION

Personality functioning and therapy adherence

This case history shows that personality functioning can be compromised and must be considered also in patients with chronic somatic symptoms. Centering, the evaluation of intra- and interpersonal functioning in the conceptual analysis of such patients, like in the case history, can lead to clinically meaningful interventions.

Following the general criteria for a personality disorder in DSM-5, significant problems in self (identity and self-direction) and interpersonal (empathy and intimacy) functioning must be given, relatively stable across time and situations[10]. However, contextual, socio-environmental factors, drugs, or medications must be excluded as causes for the disorder. For diagnosing BPD, traits in specific domains must be compromised (negative affectivity, disinhibition, antagonism)[10]. The assessment can be carried out with the Personality Inventory for DSM-5[11]. Besides a thorough psychiatric assessment including evaluation determining the treatment setting and a clear treatment framework, defining the treatment goals with the patient is important. Although for BPD patients usually symptom-targeted pharmacotherapy is necessary, psychotherapy is the primary treatment[12].

Psychoanalysts focus on specific features emerging in the patient-therapist relationship. Assessing attachment style, a personality dimension, is one of the core methods determining the choice of specific therapeutic interventions. Psychoanalysts use transference and countertransference as hints in diagnosis and therapy. For example, the insecure, ambivalent attachment pattern of the patient with her distinct expression of a need for help but conflicting and inconsistent behavior and emotions might have contributed to the confusion in the therapist (countertransference). As confirmed by a recent meta-analysis, in BPD high dropout rates are characteristic and prevalent[13].

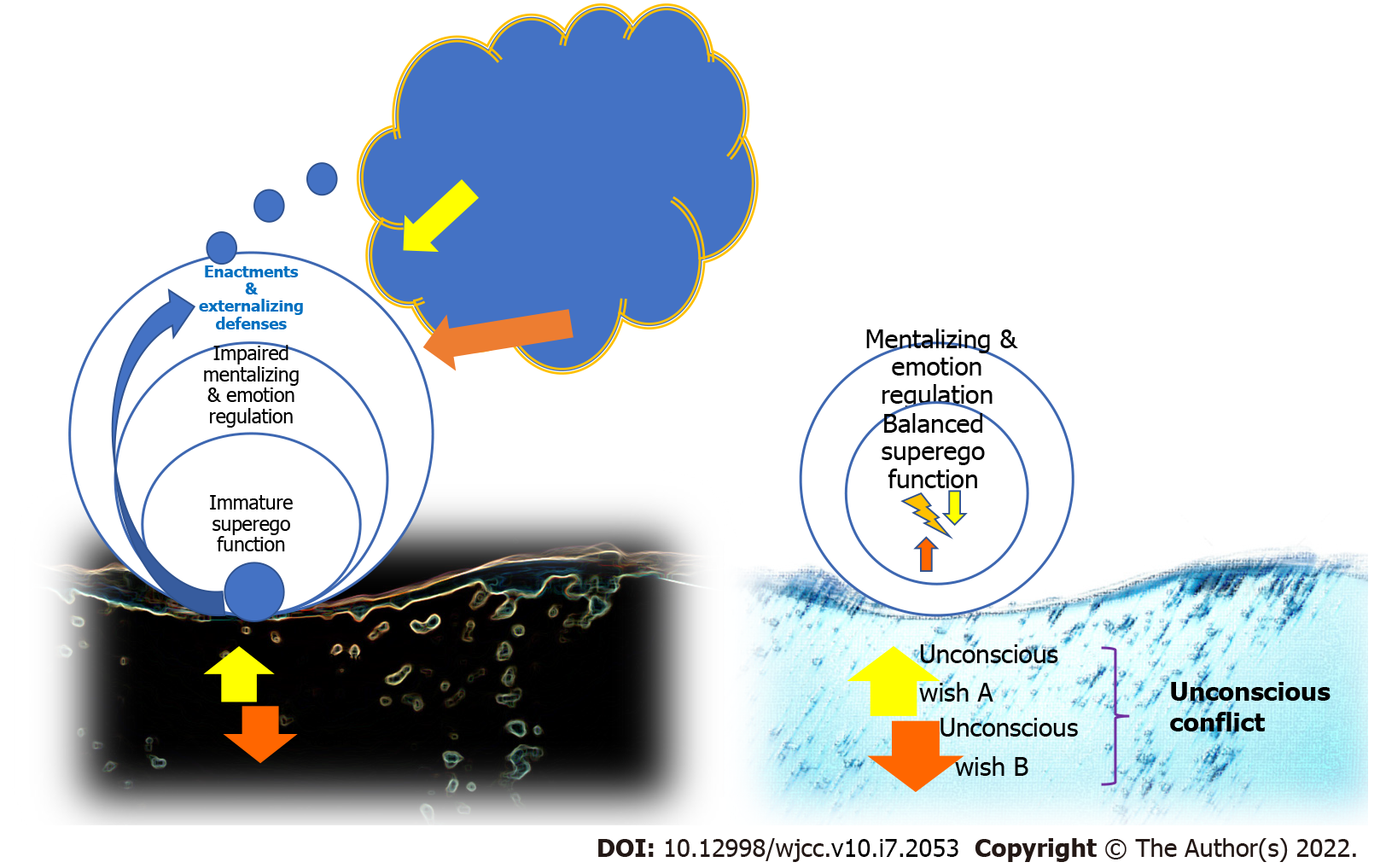

However, previous research already showed that utilization of psychotherapy was predictable based on personality pathology, affect regulation, and interpersonal functioning[14]. An ‘externalizing personality dimension,’ characterized by externalizing defenses, acting out, deficient superego functions with impaired mentalizing, was characteristic in patients not accessible for treatment (compare Figure 1). Thus, after a thorough exploration and case conceptualization, continuous contact and individualized interactions with healthcare professionals are necessary for long-term effects. Alternative approaches on how not to lose contact with patients with chronic mental disorders would be essential. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 pandemic certainly aggravated these problems. To create a feedback system in terms of an add-on eHealth tool that provides holding, reflecting[15,16], and containment of painful affects is our ambition in the long run. In addition to face-to-face psychotherapeutic interventions, a smartphone-based tool could provide hints and aid in between the therapeutic sessions and enhance unconscious learning, thus leading to enduring change. By applying psychotherapeutic interventions, subjective hidden intentions and narratives can be discovered by perspective taking and by considering the patient’s biographical circumstances using contextual knowledge.

Figure 1 Distortion affecting conscious mindset: unconscious conflicts and resistances.

An ‘externalizing personality dimension,’ characterized by externalizing defenses, acting out, deficient superego functions with impaired mentalizing, was characteristic in patients not accessible for treatment.

Research needs: Investigating the mechanism of change

When investigating mechanisms of change in psychotherapeutic sessions, this leads to investigating learning mechanisms. Current therapeutic interventions often focus on bringing information to patients, encouraging their reflecting on it, and concentrating on their conscious motivational long-term goals[17,18]. The average adherence rate of patients with chronic diseases is still below 50%[19]. People seem to forget information quickly and memorize it incorrectly[20]. Nonadherence is enhanced by distress related to the illness, depressive disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, avoidant coping, lack of control, characteristics of the treatment regimen, and chronicity[21]. Most importantly, a lack of empathy and information and a lack of trust corrodes adherence[21]. Interventions to change behavior are complex and require many interacting steps to motivate and establish persistence and stabilization strategies[22].

Unconscious learning

Unconscious learning happens without awareness of the keys (stimuli, rules) that initiate or influence it. In integrating stimuli mentally, e.g., when forming or activating associations between verbal and pictorial information, the role of cognitive and emotional unconscious processing has been highlighted[23-26]. Especially when it comes to internal working models of attachment, unconscious representations of childhood attachment experiences have been theorized to be at least as important as conscious ones[27].

Research on unconscious processing of subliminal stimuli in panic disorders suggests the existence of subliminal threat cues in panic disorder, possibly influenceable via treatment[28]. Distinguishing between conscious and unconscious knowledge proved to be difficult in experiments investigating conditioning[29]. The role of awareness in evaluative conditioning has been questioned, but recent evidence has shown that it may happen even without any knowledge of the stimulus’s valence. Investigating awareness when learning remains challenging. Results must be interpreted with caution because studies concerned with unconscious learning effects are often underpowered[30]. Further research should investigate the role of unconscious memory in therapeutic settings.

Motivation and adherence

Motivation and adherence seemed to be the most critical factors for achieving long-term maintenance of therapeutic effects. The importance of human social support components such as praise, feedback, and personalization has been highlighted[22]. Research suggests that goals guide behavior through attention, and this guidance can occur outside of a person’s awareness[23,24]. Goal commitment depends on the congruence between motives and goal and resulting self-determination[25,31]. Thereby offering an incentive for goal mastering is generally difficult without considering individual implicit motives.

Socio-environmental challenges in research

These factors have to be taken into concise consideration for chronic conditions, as changing the agency is mostly very difficult, even as experienced during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 pandemic. The influence of illness on life has to be considered and vice versa.

The impact from life to the disease has to be reconsidered as cultural/societal challenges influence change processes a lot[32,33].Thus, there is a need for person-related research, respecting ethical principles: “respect for personhood, acknowledgment of lived world, individualization, focus on researcher-participant relationships, and empowerment in decision-making”[34]. Admittedly, these concepts might be difficult to apply when looking at larger samples, which is a shortcoming.

Proper risk stratification and appropriate preventive and therapeutic interventions rely on conceptions of frameworks for the associations between the following factors: environment behavioral factors, genetics, demographics and comorbidities, psychosocial conditions. Emphasis on an accurate assessment and diagnosis at first should result in more personalized handling of patients[35] and efficient resource allocation when scant. Potential confounding variables and effect measure modifiers have to be considered and assessed (e.g., symptom severity, age, education).

Process-oriented research to unveil mechanisms of unconscious interaction

Process-oriented research is based on analysis of singular sessions based on recordings, also carried out for the example presented above. Moreover, being video-recorded and getting individualized feedback fosters mental processes, leading to changes in attitudes and beliefs as predicted by the concept of objective self-awareness introduced by Duval and Wicklund[36].

By definition, process-oriented approaches involve analysis of changes over time or across different contexts in an individual, in terms of specific variables that either have been selected by the patient or were derived from individually tailored assessment stimuli/contexts to maximize their relevance for the individual[37]. In particular, the investigation of therapeutic microprocesses, small but essential aspects of the interaction, brings promising insight into therapy’s mechanism and identifies specific factors necessary for successful treatment and influencing unconscious processing and learning. Concerning the treatment relationship, several nonverbal events are unconscious and can often convey a patient’s emotional and mental state in a way that verbal communication cannot[38]. Phenomenological philosophical concepts of empathy[39-41] claim that visible bodily expressions and resonance shed light on others’ inner mental states and enable us to “experience others’ minds”[28]. Within this empathic understanding, bodily resonance is supposed to be accompanied by contextual knowledge and differentiation between self and others.

Investigating nonverbal communication: emotional signals from faces and bodies

Emotional signals from the face can be studied via analysis of facial expressions, including so-called ‘microexpressions,’ subtle movements lasting less than 1/25 to 1/5 of a second[42,43]. Recognition of the facial microexpression depends on its duration and is theorized to occur subliminally, but conscious recognition can be practiced[43]. Microexpressions can neither be controlled nor voluntarily displayed and offer a valid and authentic view into a person’s genuine feelings and emotions[44]. They can be understood as either repressed or unconscious expressions of emotions[45-47]. When they are addressed adequately by clinicians, this has positive impacts on the working alliance between treating clinician and patient, essential for the outcome of treatment[47] as well as on adherence to treatment per se, what we have already shown[48]. Furthermore, therapeutic sessions with higher levels of nonverbal microaffectivity have been rated as having more impact on patient outcomes[49]. Facial microexpressions during video-recordings can give insights into what works for whom in which way[49-51]. For example, the case history of the patient was characterized by sessions particularly loaded with affective content; containing and interpreting affective signals allowed to establish a therapeutic relationship stable enough for interventions.

Body language and behavior

Individual unconscious influences on behavior have been discussed together with concepts of intentionality, agency, responsibility, and compatibility of freedom of decision[52-55]. The analysis of expressions, behavior, and other enactments as an unbiased expression of intentionality is seen as problematic in psychoanalysis; consciousness is a necessary precondition for a sense of agency, intentionality, and freedom. Thus, helping the patient gain insights into previously unconscious motives, conflicts, and intentions sets the starting point for a self-determined life. The patient’s acting out (language, motor expressions) can only be used as a surrogate and starting point for the analysis.

Nevertheless, analysis of videotaped sessions leads to measures of affective dyadic behavior. Investigation of facial action units is one possibility to discern underlying emotions[47,56,57]. Perception of illness and therapist/patient relation (Working Alliance Inventory[58]) can be evaluated with questionnaires likewise as emotion regulation and quality of life.

Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis is the science of the unconscious and is dedicated to investigating unconscious fantasies and conflicts with unique findings. Hence treatments are deeply rooted in an empirically derived still growing theory. Influences on all other psychotherapeutic paradigms are undeniable. As mentioned above, long-term results in the psychoanalytic setting are achieved in individually tailored interventions concerning unconscious processing and reshaping emotional memories. For psychodynamic therapy, it has been shown that therapists with better management of difficult countertransference achieved the best results. Countertransference is the sum of the therapist’s feelings towards the patient’s transference or therapist’s feelings initially provoked by the patient in the therapist. That said, emotion regulation abilities and mentalizing skills are key processes when aiming at shaping long-term behavior. In fact, evidence for influences of the therapist’s expertise in emotion differentiation, in experiencing a range of emotions and in clarity, regarding the understanding of causes and effects of one’s feelings on accuracy in perceiving the patient’s inner mental states has already been provided[59-61]. When looking at individual emotion regulation profiles, the concept of mentalized affectivity provides an evidence-based model. It includes three factors: identifying, processing, and expressing emotions. Interactions with the environment are integrated with prior cognitive and affective schemas. Thus, feedback is implemented continuously.

Human behavior is more or less goal-directed, with reward and loss incentives as the strongest motivators and cognitive controls overriding influence on whether the plan is put into practice[62,63]. Evidence exists for overlapping neuronal pathways involved when cue-mediated craving becomes manifest for various stimuli (alcohol, drugs of abuse, food, sex, gambling[64]). The circuits involved in addictive behavior are likewise relevant when looking at the processing of reward, emotion regulation, nondeclarative memory, and obsessive-compulsive behavior[64]. Thus, ‘novelty seeking’ and addiction seem to be related as the brain’s central reward system and neurotransmitter dopamine are involved in both traits[65]. However, so far association but no causality between human sensation seeking and addiction has been shown[65].

Regulation of inner mental and affective states through self-reflection, leading to containment and healthy behavior without denying destructive tendencies and the necessary reality check in psychoanalytic theorizing is a superego function. The formation of the superego includes the development of internalized ideals acquired from parents and society. The superego’s function includes suppressing drives and instincts, to behave morally, according to the ego ideal. If values and internalized rules are not respected, feelings of guilt may arise; the image of the own self might be divested from pride and value. The therapeutic alliance and transference work create room for changing the patient’s relation to his superego, shaping it to allow for the beneficial aspects unconscious processing can convey while the therapist’s focus is on influencing the quality of object relations[66]. Suppose emotional and psychic responses of patients to their realities are observed and reflected compassionately. In that case, the harshness of their superego (e.g., in obsessive-compulsive disorder) can be contained and used as a signal instead of a threat to (psychic) existence.

Reconsolidation of memories

Memory has long been seen as something static. This concept has been questioned[67]. The reactivation of long-term memories makes them vulnerable to change. Especially remote memories and memories of narrative structure are thought to return to a plastic state upon their reactivation with new information intruding into the original memory[67]. With Lane et al[68], we promote the hypothesis that permanent change in psychotherapy is partly achieved via reconsolidation of memories. A recent meta-analysis has shown that modification of maladaptive memories during reconsolidation could be a treatment strategy for substance use and phobias/trauma disorders[69]. Based on the “reconsolidation of memories” hypothesis and in conclusion, further research should focus on the question of how modulation of maladaptive memories occurs. Together with interventions based on the existence of neuroplasticity in general (e.g., dance and sports interventions[70]), the functional decline could be influenced via shaping the patients’ memories.

In retrieval-dependent treatments, reconsolidation could result in transformation as follows: while activating a memory with the affect initially associated with this memory, new emotional experiences are facilitated during treatment, further letting them be incorporated in this memory and reinforcing the updated memory[68]. Learning and long-term remembering of new knowledge frameworks and concepts, leading to a changed perception and understanding, are strongly shaped by intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and the individuals’ emotions in the context of interpersonal relationships[71]. Skill and habit formation are part of the nondeclarative long-term memory system; they are somewhat feedback-based and enhanced by reward. Declarative learning involves retrieval of memories (episodic, semantic) and the formation and application of categories and rules by associative thinking and by making generalizations[71]. The integrative memory model states that whenever speaking of memory, all systems (e.g., semantic, episodic, and emotional) must be considered active at the same time[68] with interactions between them. It is well known that emotional experiences are generally prioritized over neutral ones, thus persisting and shaping long-term memory with influences on a person’s behavior. Even enhancement of long-term memory for impartial information is known to be better when associated directly with an emotional event and before an anticipated impending source of arousal[72,73].

In consequence of that, highly emotional and accessible memories influence a future response in somewhat similar situations. Psychoanalysts’ interventions are based on recalling past emotional events aiming to consciously understand the emotions evoked. The therapy consists of inducing a corrective emotional experience in the patient. In the working-through process, the re-experiencing and revaluating of the newly shaped memory with associated emotional responses are applied in many different contexts, thus creating many episodic experiences and a complete picture of reality. A vital element of the intervention is the clinician’s current interactive experience in the actual interaction, a new experiencing the self with others. However, there is no way of changing altered and dysfunctional reactions without being affectively noticed and contained. However, research is needed to further investigate the mechanism of change.

CONCLUSION

Subliminal affect-perception is enabled via awareness of subjective meanings in oneself and the other; shaping this awareness is the primary intervention point. The interactional ingredients, the patient’s inherent bioenvironmental history meeting the clinician – are target variables. Interventions aiming at supporting the internalization of the superego’s functions in moments of self-reflection result in a better understanding of oneself. Higher self-regulation can lead to better judgments and facilitate enduring behavior change.

Treatment interventions at the beginning of a therapeutic process are aimed at establishing a stable patient-therapist relationship. Interventions must be structured and address the dominant affect, while affective containment is necessary. The example given in this paper shows that in personality disorder from the psychoanalyst’s point of view specific personality characteristics and defense mechanisms must be addressed in order to prevent therapy dropout and self-sabotage of the therapeutic relationship[14]. Awareness of unconscious motives, conflicts, and intentions is a starting point for change in accordance with the patient’s psyche. The reconsolidation of memories hypothesis sees the patient’s maladaptive memories as something plastic and shapable through therapy. Although existing findings on the plasticity of memories and on unconscious learning should be interpreted with caution, further research should investigate the mechanism of change. Rigorous studies with long-term follow-ups, including a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, are required to investigate the linkage between awareness, learning, and effectiveness of interventions aiming at memory reconsolidation.

Taken together, both the motivation and the ability to influence one’s life condition have to be freed to increase self-efficacy and a pleasurable pursuit of life. In psychoanalytic thinking, conflicting motives and/or goals demanding painful sacrifices need to be considered when initially effective interventions fail to induce a relevant change in the end. Social and other contextual external factors or inborn predispositions apply when problem-solving fails[8,75].

To create an inner sphere of autonomy for patients despite disease, providing room for development based on a deeper understanding of one’s mind and emotional life with the possibility to lead a more congruent life is the basic idea.

There still is a research gap concerning the optimal length of psychodynamic psychotherapeutic interventions and long-term follow-up with randomized controlled trials. There is a relatively small difference in the 10-year follow-up when confronting short-term vs long-term interventions[74]. Furthermore, relational problems occurring between or among individuals contribute to distress and risk for a poor functional outcome. Thus, relational problems should be better implemented in diagnosis and therapeutic strategies[75]. The development of reliable and standardized assessments of relational processes is crucial[76].