Abstract

Background

In patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) with an asymptomatic primary tumor, there is no consensus on the indication for resection of the primary tumor.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on the outcome of stage IV colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with or without resection of the primary tumor treated in the phase III CAIRO and CAIRO2 studies. A review of the literature was performed.

Results

In the CAIRO and CAIRO2 studies, 258 and 289 patients had undergone a primary tumor resection and 141 and 159 patients had not, respectively. In the CAIRO study, a significantly better median overall survival and progression-free survival was observed for the resection compared to the nonresection group, with 16.7 vs. 11.4 months [P < 0.0001, hazard ratio (HR) 0.61], and 6.7 vs. 5.9 months (P = 0.004; HR 0.74), respectively. In the CAIRO2 study, median overall survival and progression-free survival were also significantly better for the resection compared to the nonresection group, with 20.7 vs. 13.4 months (P < 0.0001; HR 0.65) and 10.5 vs. 7.8 months (P = 0.014; HR 0.78), respectively. These differences remained significant in multivariate analyses. Our review identified 22 nonrandomized studies, most of which showed improved survival for mCRC patients who underwent resection of the primary tumor.

Conclusions

Our results as well as data from literature indicate that resection of the primary tumor is a prognostic factor for survival in stage IV CRC patients. The potential bias of these results warrants prospective studies on the value of resection of primary tumor in this setting; such studies are currently being planned.

Similar content being viewed by others

For most patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), there are no curative options, but a benefit in median overall survival (OS) can be achieved with palliative systemic treatment.1 This treatment currently consists of cytotoxic chemotherapy and targeted therapy. The 5-year OS for patients who are diagnosed with distant metastases ranges 10–20%.2 – 4 The median OS is improved when patients are exposed to all available cytotoxic drugs during the course of their disease.5 Because the disease of only a subset of patients will respond to systemic treatment, we need predictive and prognostic markers that will permit us to select patients who may experience the optimal benefit of available treatments. Currently available biomarkers are not predictive for the efficacy of chemotherapy, and for targeted therapy, only KRAS mutation status is predictive for response to anti–epidermal growth factor receptor therapy, with BRAF mutation status being a candidate prognostic marker.6 – 8

Patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) with stage IV disease may manifest various symptoms of their primary tumor and/or metastases, and a palliative resection of the primary tumor before the initiation of systemic treatment is frequently performed.9 This indication is obvious in patients with a symptomatic primary. However, in patients with few or absent symptoms, the indication for resection is under debate, and its effect on survival and quality of life is still uncertain.10 – 12 The possible influence of a palliative resection of the primary tumor on survival has never been properly assessed, and most randomized studies in mCRC do not even report whether a resection of the primary tumor has been performed.13 , 14

We here report a retrospective analysis of two phase III studies on the prognostic and predictive value of resection of the primary tumor in stage IV mCRC patients.15 , 16 Data on the toxicity of systemic treatment in resected versus nonresected patients are presented. We review the literature on this issue and discuss our data in relation to the results of this review.

Methods

CAIRO Studies

Data of metastatic CRC patients included in two phase III studies (CAIRO and CAIRO2) of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group were used (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00312000 and NCT00208546). Details of these studies have been published elsewhere.15 – 18

Patients with stage IV disease (metastatic disease at diagnosis) were classified as having undergone a resection (resection group) or no resection (nonresection group) of the primary tumor before randomization in the study. Patients who had undergone a resection of the primary tumor after randomization and patients who had an incomplete resection of the primary tumor before randomization were included in the nonresection group. To assess the prognostic value of resection, we analyzed the total group of patients in each study with stage IV disease and compared the outcome of the resection group with the nonresection group. To assess the predictive value of resection, we analyzed the interaction of resection with the outcome of first-line treatment per treatment arm in each study. Toxicity was scored according to U.S. National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0.

Statistical Methods

Ineligible patients were excluded from the analysis. The progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of randomization to the first observation of disease progression or death from any cause. OS and PFS curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log rank test. Multivariate analysis of survival was performed by the Cox proportional hazard model. The comparison of factors between groups (resection vs. nonresection) was performed by chi-square, Fisher’s exact, or Mann-Whitney tests, where appropriate. All tests were two-sided, and P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed by SAS 9.1 and S-plus 6.2 software.

Literature Search Strategy, Inclusion Criteria, and Data Extraction

We reviewed the literature on the prognostic and/or predictive value of resection of the primary tumor in mCRC patients with unresectable distant metastases. The primary outcomes of interest were OS, toxicity, and morbidity. A search was conducted of Medline, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library from January 1980 to December 2010 with an English-language restriction.

Original publications were selected if the abstract contained safety and efficacy data for patients with and without resection of the primary tumor. In case of duplicate publications, the most recent and/or most complete study was included. We excluded cohorts of patients with mCRC who were candidates for potentially curative metastasectomy, and publications that included only rectal cancer or merely focused on the surgical procedure.

Results

CAIRO Study

Patient Characteristics

Of the 803 eligible patients with advanced CRC disease in the CAIRO study, 399 patients had stage IV disease at inclusion. Of these patients, 258 were placed in the resection group and 141 patients in the nonresection group. Patients in the nonresection group more often had abnormal baseline serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), more often had predominant extrahepatic metastases, more often had a primary tumor located in rectosigmoid or rectum, and received fewer cycles of chemotherapy (Table 1). At baseline, none of the patients had grade 3–4 nausea, vomiting, or ileus toxicity. Only two patients in the nonresection group had grade 3–4 diarrhea toxicity at presentation (P = 0.06).

Prognostic Value of Resection of the Primary Tumor

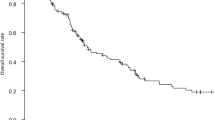

A significantly better median OS and PFS was observed for patients in the resection versus the nonresection group, with 16.7 vs. 11.4 months [P < 0.0001; hazard ratio (HR) 0.61, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49–0.76] (Fig. 1), and 6.7 vs. 5.9 months (P = 0.004; HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60–0.91), respectively. A multivariate analysis was performed that included baseline serum LDH, predominant localization of metastases, performance status, localization of the primary tumor, and chemotherapy schedule. Resection of the primary tumor was prognostic for OS and borderline prognostic for PFS in patients with only one metastatic site (P = 0.016, HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.43–0.92, and P = 0.069, HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.30–1.25), but not in patients with two or more metastatic sites (P = 0.276, HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.70–1.11, and P = 0.444, HR 1.10, 95% CI 0.87–1.38).

Predictive Value of Resection of the Primary Tumor

The primary objective of the CAIRO study was to evaluate sequential versus combination chemotherapy. No significant interaction with sequential versus combination treatment in respect to median OS was observed for patients in the resection group (16.2, 95% CI 13.5–29.4 vs. 17.6 months, 95% CI 14.8–20.1) and the nonresection group (9.8, 95% CI 7.9–11.8, vs. 14.9 months, 95% CI 10.8–16.4) (P = 0.769).

Toxicity

We assessed a possible interaction for patient symptoms that may have been related to the presence of the primary tumor—that is, nausea, vomiting, ileus, diarrhea, and fatigue.

In first-line treatment, none of the instances of grade 3–4 toxicity occurred significantly more frequently in the nonresection group compared to the resection group. When all treatment lines were considered, the incidence of grade 3–4 vomiting and ileus in the overall study population occurred significantly more frequently in the nonresection compared to the resection group, with 11% vs. 5% for vomiting (P = 0.053) and 7% vs. 2% for ileus (P = 0.019), respectively. In the sequential treatment arm, nausea and fatigue occurred significantly more frequently in the nonresection compared to the resection group; 13% vs. 5% (P = 0.054) and 33% vs. 18% (P = 0.014), respectively. In the combination treatment arm, only grade 3–4 ileus occurred significantly more frequently in the nonresection compared to the resection group, 10% vs. 3% (P = 0.029).

CAIRO2 Study

Patient Characteristics

Of the 736 eligible mCRC patients in the CAIRO2 study, 448 patients had stage IV disease at inclusion. Of these patients, 289 were assigned to the resection group and 159 patients to the nonresection group. Patients in the nonresection group were more often men, were younger, more often had abnormal baseline serum LDH, had a worse performance status, and more often had liver plus other metastases and a larger number of metastatic sites compared to the resection group (Table 2). At baseline, none of the patients presented with grade 3–4 nausea, vomiting, or ileus toxicity. Only one patient in the nonresection group had grade 3–4 diarrhea toxicity at presentation (P = 0.178).

Prognostic Value of Resection of the Primary Tumor

A significantly better median OS and PFS were observed for patients in the resection versus the nonresection group, with 20.7 vs. 13.4 months (P < 0.0001; HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.52–0.80) (Fig. 2), and 10.5 vs. 7.8 months (P = 0.015; HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.64–0.95), respectively.

In the multivariate analysis that included sex, age, baseline serum LDH, performance status, localization of metastases, localization of primary tumor, number of metastatic sites involved, and treatment arm, resection of the primary tumor remained an independent prognostic factor for median OS (P = 0.010; HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58–0.93), but not for PFS (P = 0.130; HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.68–1.05).

Predictive Value of Resection of the Primary Tumor

The primary objective of the CAIRO2 study was to evaluate the addition of cetuximab to capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab. No significant interaction with treatment was observed in respect to median OS for patients in the resection group (21.6, 95% CI 17.6–27.8 vs. 20.2 months, 95% CI 17.1–22.2) and the nonresection group (13.4, 95% CI 11.7–18.4 vs. 13.8 months, 95% CI 10.9–17.8) (P = 0.612).

Toxicity

We assessed a possible interaction for patient symptoms that may have been related to the presence of the primary tumor—that is, nausea, vomiting, ileus, diarrhea, and fatigue.

For the overall study population, grade 3–4 nausea, vomiting, ileus, and fatigue toxicity occurred significantly more frequently in the nonresection compared to the resection group, 9% vs. 3% for nausea (P = 0.004), 9% vs. 4% for vomiting (P = 0.043), 8% vs. 3% for ileus (P = 0.019), and 23% vs. 13% for fatigue (P = 0.004), respectively.

In the treatment arm without cetuximab, grade 3–4 nausea, vomiting, and fatigue occurred significantly more frequently in the nonresection group compared to the resection group, 13% vs. 4% for nausea (P = 0.015), 15% vs. 4% for vomiting (P = 0.003), and 21% vs. 11% (P = 0.046) for fatigue, respectively. In the treatment arm with cetuximab, only grade 3–4 fatigue occurred significantly more frequently in the nonresection group compared to the resection group; 25% vs. 14% (P = 0.042).

Review of the Literature

The literature search identified 22 nonrandomized, single-center studies (Tables 3 and 4). Twenty-one studies were retrospective, and one study concerned a case-matched cohort analysis.13 , 19 – 39 Two studies were restricted to patients without symptoms of their primary tumor.23 , 25

Definition of nonresection was defined either as surgical intervention without resection (group 1; 12 studies; Table 3) or as no surgical intervention (group 2; 12 studies; Table 4). In both groups, resection was defined as a resection of the primary tumor. Two studies used both definitions for nonresection, and therefore we present the results of these studies in the analysis of both groups.24 , 29

In group 1, the median OS was statistically significantly better in resected versus nonresected patients in 8 of 12 studies.13 , 19 , 21 , 27 , 28 , 35 , 37 , 38 The conclusion of most of these studies was that resection should be performed if feasible, in particular in symptomatic patients (Table 3).13 , 21 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 37 Two studies presented a subgroup analysis in asymptomatic patients, and although patients who underwent resection had a significantly better median OS compared to patients without resection, both studies suggested that nonresection of the primary tumor is a valid treatment choice in this setting.35 , 37 This was supported in one study by a multivariate analysis that identified chemotherapy as the only prognostic factor for OS in asymptomatic patients, and in the other by the fact that the advantages of primary tumor resection in asymptomatic patients are outweighed by perioperative mortality.35 , 37 The postoperative mortality was higher in the nonresection group (0–36%) compared to the resection group (3–16%) in 5 of 12 studies. The incidence of postoperative morbidity ranged 3–50% in the resection group versus 0–38% in the nonresection group.

In group 2, 6 of 12 studies demonstrated an improved median OS in the resection compared to the nonresection group (Table 4).20 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 29 , 33 In three studies a subset of patients was reported to be asymptomatic in relation to their primary tumor,33,34,39 of which the largest study showed a significant benefit in OS for patients with a resection of the primary tumor.33 The postoperative mortality ranged 0–16%, and the postoperative morbidity ranged 10–34.7% (Table 4). In 8 of 12 studies, both the resected and nonresected groups received chemotherapy.20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 31 , 36 , 39 Tebbutt et al. 36 suggested that most patients who do not require surgical intervention for complications of their primary tumor at the time of diagnosis can be safely treated with chemotherapy because no increase of intestinal complications was observed.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first retrospective analysis of two phase III studies investigating the prognostic and predictive value of resection of the primary tumor in patients with stage IV CRC treated with systemic therapy. We identified resection of the primary tumor as a prognostic factor for OS. Resection was not predictive in relation to the outcome of treatment that was used in these studies. We observed a higher incidence of toxicity in the nonresected group, in particular in the CAIRO2 study.

It seems plausible that a resection was performed or at least attempted in patients who had symptoms that demanded urgent surgical treatment. However, a major limitation of our study is that the decision to resect the primary tumor was made before study entry, and thus we have no information about the reasons for nonresection, such as irresectability of the primary tumor, poor condition of the patient, symptomatic metastases requiring priority for systemic treatment, or absence of symptoms of the primary tumor. Obviously, these concern arguments of a highly different nature and may define different patient populations. For instance, the fact that patients in the nonresection group more often had an elevated serum LDH and a larger number of metastatic sites may have shifted the decision of the treating physician toward nonresection. However, when these variables were included in a multivariate analysis, resection of the primary tumor remained a prognostic factor in the CAIRO2 study and in the subgroup of patients with one metastatic site in the CAIRO study.

What can we learn from our review on this subject? The studies that we identified were of nonrandomized design, performed in a single center, and retrospective of nature, with only one exception. Taken together, the data were in favor of a resection of the primary tumor in patients with symptomatic lesions. In asymptomatic patients, the results are less clear, although the median OS was improved in resected patients in most studies. An important limitation of these studies is that few if any data on the use of systemic therapy were presented, which, given its impact on survival, makes it difficult to assess the relative contribution of resection to outcome.

The two main objectives in the management of patients with irresectable mCRC are to improve or maintain the quality of life and to prolong survival. The treatment strategy in patients with stage IV disease and a symptomatic primary tumor usually consists of initial resection of this tumor, followed by palliative systemic treatment. In patients with few or absent symptoms of the primary tumor, arguments both in favor and against initial resection have been presented. The most dominant argument in favor of initial resection is the prevention of complications of the primary tumor with subsequent prolongation of symptom-free survival and OS.29 , 40 , 41 Furthermore, Stillwell et al. found that patients initially treated with chemotherapy were 7.3 times more likely to have a complication from the primary tumor, and when operated for such complications, they were more likely to have a poor postoperative outcome.33 , 39 , 42

In the United States, most patients with mCRC undergo a resection of the primary tumor.9 This is in contrast to the situation in the Netherlands, where a trend toward a nonresection approach has been observed.43 This trend might be due to the availability of new active drugs and to a more adequate selection of patients for surgery.44 Another argument in favor of resection of the primary tumor is the more accurate staging of disease because extrahepatic metastases may be better identified by visual exploration of the peritoneal cavity.25 , 31 Circumstantial evidence comes from data that show an increased growth rate of liver metastases on resection of the primary tumor, as determined by an increased vascular density, proliferation rate, and metabolic growth rate.45 – 47 These data suggest that the outgrowth of metastatic disease may at least partly be controlled by the primary tumor. However, clinical data to support this concept are lacking. The most important argument against an initial resection of the primary tumor is that the survival benefit of resection has not been demonstrated, and that the morbidity and mortality associated with surgery should therefore be avoided.28 , 34 , 48 Poultsides et al. 49 concluded that most patients with synchronous advanced CRC who receive up-front systemic therapy never require palliative surgery for their primary tumor, and that systemic therapy can be safely administered to these patients. We challenge their conclusion for two reasons. First, the median OS in their patient population with intact primary was only 13 months, while median OS times of 22–24 months are currently achieved for unselected mCRC patients. Second, we observed a higher incidence of toxicity in the nonresection group compared to the resection group, especially in the CAIRO2 study. Patients in the nonresection group experienced more nausea, vomiting, and ileus, which might be related to the primary tumor.

Scheer et al. 50 concluded that for patients with synchronous metastatic disease and an asymptomatic primary tumor, initial chemotherapy was the treatment of choice because resection of the primary tumor provides only minimal palliative benefit, can give rise to major morbidity and mortality, and therefore may delay potentially beneficial chemotherapy.

This possible detrimental effect of a delay in systemic treatment caused by initial resection is not supported by the survival benefit, as shown in the CAIRO studies. However, a selection bias in this respect cannot be excluded because patients experiencing serious morbidity after resection obviously did not qualify for the CAIRO entry criteria and were therefore not included.

Taken together, the fact that the CAIRO results are derived from clinical studies with predefined inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, and follow-up schedules in our opinion provides stronger evidence for the prognostic value of resection of the primary tumor in CRC patients with stage IV disease compared with the data from the studies as presented in our review. However, in all studies presented to date, a selection bias cannot be excluded. Therefore, prospective studies on this topic are warranted; these are currently being planned.

References

Golfinopoulos V, Salanti G, Pavlidis N, Ioannidis JP. Survival and disease-progression benefits with treatment regimens for advanced colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:898–911.

Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–83.

O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Colon cancer survival rates with the new American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition staging. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1420–5.

Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Campbell ME, et al. Five-year data and prognostic factor analysis of oxaliplatin and irinotecan combinations for advanced colorectal cancer: N9741. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5721–7.

Grothey A, Sargent D, Goldberg RM, Schmoll HJ. Survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer improves with the availability of fluorouracil–leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in the course of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1209–14.

Koopman M, Venderbosch S, Nagtegaal ID, van Krieken JH, Punt CJ. A review on the use of molecular markers of cytotoxic therapy for colorectal cancer: what have we learned? Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1935–49.

Lievre A, Bachet JB, Boige V, et al. KRAS mutations as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:374–9.

Tol J, Nagtegaal ID, Punt CJ. BRAF mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:98–9.

Cook AD, Single R, McCahill LE. Surgical resection of primary tumors in patients who present with stage IV colorectal cancer: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, 1988 to 2000. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:637–45.

Joffe J, Gordon PH. Palliative resection for colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:355–60.

Stearns MW Jr, Binkley GE. Palliative surgery for cancer of the rectum and colon. Cancer. 1954;7:1016–9.

Modlin J, Walker HS. Palliative resections in cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1949;2:767–76.

Costi R, Mazzeo A, Di Mauro D, et al. Palliative resection of colorectal cancer: does it prolong survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2567–76.

Sorbye H, Kohne CH, Sargent DJ, Glimelius B. Patient characteristics and stratification in medical treatment studies for metastatic colorectal cancer: a proposal for standardization of patient characteristic reporting and stratification. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1666–72.

Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J, et al. Sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer (CAIRO): a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:135–42.

Tol J, Koopman M, Cats A, et al. Chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:563–72.

Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J, et al. Randomised study of sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer: an interim safety analysis. A Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) phase III study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1523–8.

Tol J, Koopman M, Rodenburg CJ, et al. A randomised phase III study on capecitabine, oxaliplatin and bevacizumab with or without cetuximab in first-line advanced colorectal cancer: the CAIRO2 study of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG). An interim analysis of toxicity. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:734–8.

Aslam MI, Kelkar A, Sharpe D, Jameson JS. Ten years experience of managing the primary tumours in patients with stage IV colorectal cancers. Int J Surg. 2010;8:305–13.

Bajwa A, Blunt N, Vyas S, et al. Primary tumour resection and survival in the palliative management of metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:164–7.

Beham A, Rentsch M, Pullmann K, et al. Survival benefit in patients after palliative resection vs. non-resection colon cancer surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6634–8.

Chan TW, Brown C, Ho CC, Gill S. Primary tumor resection in patients presenting with metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of a provincial population-based cohort. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:52–5.

Seo GJ, Park JW, Yoo SB, et al. Intestinal complications after palliative treatment for asymptomatic patients with unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:94–9.

Evans MD, Escofet X, Karandikar SS, Stamatakis JD. Outcomes of resection and non-resection strategies in management of patients with advanced colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:28.

Galizia G, Lieto E, Orditura M, et al. First-line chemotherapy vs. bowel tumor resection plus chemotherapy for patients with unresectable synchronous colorectal hepatic metastases. Arch Surg. 2008;143:352–8.

Kaufman MS, Radhakrishnan N, Roy R, et al. Influence of palliative surgical resection on overall survival in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: a retrospective single institutional study. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:498–502.

Konyalian VR, Rosing DK, Haukoos JS, et al. The role of primary tumour resection in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:430–7.

Law WL, Chan WF, Lee YM, Chu KW. Non-curative surgery for colorectal cancer: critical appraisal of outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:197–202.

Liu SK, Church JM, Lavery IC, Fazio VW. Operation in patients with incurable colon cancer—is it worthwhile? Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:11–4.

Makela J, Haukipuro K, Laitinen S, Kairaluoma MI. Palliative operations for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:846–50.

Michel P, Roque I, Di Fiore F, et al. Colorectal cancer with non-resectable synchronous metastases: should the primary tumor be resected? Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:434–7.

Mik M, Dziki L, Galbfach P, Trzcinski R, Sygut A, Dziki A. Resection of the primary tumour or other palliative procedures in incurable stage IV colorectal cancer patients? Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:e61–67.

Ruo L, Gougoutas C, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Cohen AM, Wong WD. Elective bowel resection for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: prognostic variables for asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:722–8.

Scoggins CR, Meszoely IM, Blanke CD, Beauchamp RD, Leach SD. Nonoperative management of primary colorectal cancer in patients with stage IV disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:651–7.

Stelzner S, Hellmich G, Koch R, Ludwig K. Factors predicting survival in stage IV colorectal carcinoma patients after palliative treatment: a multivariate analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:211–7.

Tebbutt NC, Norman AR, Cunningham D, et al. Intestinal complications after chemotherapy for patients with unresected primary colorectal cancer and synchronous metastases. Gut. 2003;52:568–73.

Yun HR, Lee WY, Lee WS, Cho YB, Yun SH, Chun HK. The prognostic factors of stage IV colorectal cancer and assessment of proper treatment according to the patient’s status. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1301–10.

Frago R, Kreisler E, Biondo S, Salazar R, Dominguez J, Escalante E. Outcomes in the management of obstructive unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:1187–94.

Benoist S, Pautrat K, Mitry E, Rougier P, Penna C, Nordlinger B. Treatment strategy for patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1155–60.

Rosen SA, Buell JF, Yoshida A, et al. Initial presentation with stage IV colorectal cancer: how aggressive should we be? Arch Surg. 2000;135:530–4.

Kuo LJ, Leu SY, Liu MC, Jian JJ, Hongiun CS, Chen CM. How aggressive should we be in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1646–52.

Stillwell AP, Buettner PG, Ho YH. Meta-analysis of survival of patients with stage IV colorectal cancer managed with surgical resection versus chemotherapy alone. World J Surg. 2010;34:797–807.

van Steenbergen LN, Elferink MA, Krijnen P, et al. Improved survival of colon cancer due to improved treatment and detection: a nationwide population-based study in the Netherlands, 1989–2006. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2206–12.

Meulenbeld HJ, van Steenbergen LN, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Lemmens VE, Creemers GJ. Significant improvement in survival of patients presenting with metastatic colon cancer in the south of the Netherlands from 1990 to 2004. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1600–4.

Peeters CF, Westphal JR, de Waal RM, Ruiter DJ, Wobbes T, Ruers TJ. Vascular density in colorectal liver metastases increases after removal of the primary tumor in human cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:554–9.

Peeters CF, de Waal RM, Wobbes T, Westphal JR, Ruers TJ. Outgrowth of human liver metastases after resection of the primary colorectal tumor: a shift in the balance between apoptosis and proliferation. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1249–53.

Scheer MG, Stollman TH, Vogel WV, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ, Ruers TJ. Increased metabolic activity of indolent liver metastases after resection of a primary colorectal tumor. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:887–91.

Sarela AI, Guthrie JA, Seymour MT, Ride E, Guillou PJ, O’Riordain DS. Non-operative management of the primary tumour in patients with incurable stage IV colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1352–6.

Poultsides GA, Servais EL, Saltz LB, et al. Outcome of primary tumor in patients with synchronous stage IV colorectal cancer receiving combination chemotherapy without surgery as initial treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3379–84.

Scheer MG, Sloots CE, van der Wilt GJ, Ruers TJ. Management of patients with asymptomatic colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable metastases. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1829–35.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG).

Disclosure

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Venderbosch, S., de Wilt, J.H., Teerenstra, S. et al. Prognostic Value of Resection of Primary Tumor in Patients with Stage IV Colorectal Cancer: Retrospective Analysis of Two Randomized Studies and a Review of the Literature. Ann Surg Oncol 18, 3252–3260 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-1951-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-1951-5