Abstract

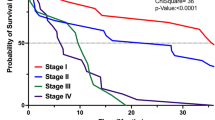

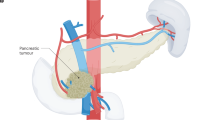

Pancreatic cancer is likely to become the second most frequent cause of cancer-associated mortality within the next decade. Surgical resection with adjuvant systemic chemotherapy currently provides the only chance of long-term survival. However, only 10–20% of patients with pancreatic cancer are diagnosed with localized, surgically resectable disease. The majority of patients present with metastatic disease and are not candidates for surgery, while surgery remains underused even in those with resectable disease owing to historical concerns regarding safety and efficacy. However, advances made over the past decade in the safety and efficacy of surgery have resulted in perioperative mortality of around 3% and 5-year survival approaching 30% after resection and adjuvant chemotherapy. Furthermore, owing to advances in both surgical techniques and systemic chemotherapy, the indications for resection have been extended to include locally advanced tumours. Many aspects of pancreatic cancer surgery, such as the management of postoperative morbidities, sequencing of resection and systemic therapy, and use of neoadjuvant therapy followed by resection for tumours previously considered unresectable, are rapidly evolving. In this Review, we summarize the current status of and new developments in pancreatic cancer surgery, while highlighting the most important research questions for attempts to further optimize outcomes.

Key points

-

Surgical resection in combination with systemic chemotherapy offers the only hope for long-term survival or cure in patients with nonmetastatic pancreatic cancer.

-

Surgical resection and adjuvant multi-agent chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus capecitabine or modified FOLFIRINOX) is the standard of care in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer.

-

Both the safety and efficacy of pancreatic cancer surgery have improved considerably in the past decade, enabling perioperative mortality of around 3% and 5-year survival approaching 30–40% after resection and chemotherapy.

-

Important criteria for assessing the quality of pancreatic cancer surgery include perioperative morbidity and mortality, oncologically determined pancreatic resection, the proportion of patients in fact receiving and completing adjuvant therapy and — above all — long-term survival.

-

Relationships between hospital pancreatectomy volume and outcome quality have an important role in determining the success of pancreatic cancer surgery.

-

Owing to advances in both surgery and systemic chemotherapy, the indications for surgical resections have been extended from stage I and II to locally advanced, previously unresectable pancreatic cancer.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 7–30 (2018).

Rahib, L. et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 74, 2913–2921 (2014).

Hartwig, W., Werner, J., Jäger, D., Debus, J. & Büchler, M. W. Improvement of surgical results for pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 14, e476–e485 (2013).

Kleeff, J. et al. Pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2, 16022 (2016).

Gillen, S., Schuster, T., Meyer Zum Buschenfelde, C., Friess, H. & Kleeff, J. Preoperative/neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of response and resection percentages. PLOS Med. 7, e1000267 (2010).

Hackert, T. et al. Locally advanced pancreatic cancer: neoadjuvant therapy with folfirinox results in resectability in 60% of the patients. Ann. Surg. 264, 457–463 (2016).

Bilimoria, K. Y. et al. National failure to operate on early stage pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 246, 173–180 (2007).

Shah, A. et al. Trends in racial disparities in pancreatic cancer surgery. J. Gastrointestinal Surg. 17, 1897–1906 (2013).

Huang, L. et al. Resection of pancreatic cancer in Europe and USA: an international large-scale study highlighting large variations. Gut https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314828 (2017).

Gooiker, G. A. et al. Impact of centralization of pancreatic cancer surgery on resection rates and survival. Br. J. Surg. 101, 1000–1005 (2014).

Gooiker, G. A. et al. Quality improvement of pancreatic surgery by centralization in the western part of the Netherlands. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 18, 1821–1829 (2011).

Krautz, C., Nimptsch, U., Weber, G. F., Mansky, T. & Grutzmann, R. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital morbidity and mortality following pancreatic surgery in Germany. Ann. Surg. 267, 411–417 (2018).

Lidsky, M. E. et al. Going the extra mile: improved survival for pancreatic cancer patients traveling to high-volume centers. Ann. Surg. 266, 333–338 (2017).

Ansari, D., Aronsson, L., Fredriksson, J., Andersson, B. & Andersson, R. Safety of pancreatic resection in the elderly: a retrospective analysis of 556 patients. Ann. Gastroenterol. 29, 221–225 (2016).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Age 80 years and over is not associated with increased morbidity and mortality following pancreaticoduodenectomy. ANZ J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.14039 (2017).

Shamali, A. et al. Elderly patients have similar short term outcomes and five-year survival compared to younger patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Int. J. Surg. 45, 138–143 (2017).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389, 1011–1024 (2017).

Uesaka, K. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial (JASPAC 01). Lancet 388, 248–257 (2016).

Asbun, H. J. et al. When to perform a pancreatoduodenectomy in the absence of positive histology? A consensus statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery. Surgery 155, 887–892 (2014).

Tuveson, D. A. & Neoptolemos, J. P. Understanding metastasis in pancreatic cancer: a call for new clinical approaches. Cell 148, 21–23 (2012).

Allen, V. B., Gurusamy, K. S., Takwoingi, Y., Kalia, A. & Davidson, B. R. Diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy following computed tomography (CT) scanning for assessing the resectability with curative intent in pancreatic and periampullary cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7, CD009323 (2016).

Halloran, C. M. et al. Carbohydrate antigen 19.9 accurately selects patients for laparoscopic assessment to determine resectability of pancreatic malignancy. Br. J. Surg. 95, 453–459 (2008).

Hartwig, W. et al. CA19-9 in potentially resectable pancreatic cancer: perspective to adjust surgical and perioperative therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 20, 2188–2196 (2013).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pancreatic cancer in adults: diagnosis and management (NICE, 2018).

Motosugi, U. et al. Detection of pancreatic carcinoma and liver metastases with gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging: comparison with contrast-enhanced multi-detector row CT. Radiology 260, 446–453 (2011).

Tsurusaki, M., Sofue, K. & Murakami, T. Current evidence for the diagnostic value of gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for liver metastasis. Hepatol. Res. 46, 853–861 (2016).

Ghaneh, P. et al. PET-PANC: multicentre prospective diagnostic accuracy and health economic analysis study of the impact of combined modality 18fluorine-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography with computed tomography scanning in the diagnosis and management of pancreatic cancer. Health Technol. Assess. 22, 1–114 (2018).

Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal, I. et al. ACR appropriateness criteria((R)) staging of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Am. Coll. Radiol 14, S560–S569 (2017).

van der Gaag, N. A. et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 129–137 (2010).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer: current and future perspectives. Nat. Rev..Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 333–348 (2018).

Bassi, C. et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 138, 8–13 (2005).

Bassi, C. et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 161, 584–591 (2017).

Wente, M. N. et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery 142, 20–25 (2007).

Wente, M. N. et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 142, 761–768 (2007).

Strobel, O. et al. Incidence, risk factors and clinical implications of chyle leak after pancreatic surgery. Br. J. Surg. 104, 108–117 (2017).

Besselink, M. G. et al. Definition and classification of chyle leak after pancreatic operation: a consensus statement by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery. Surgery 161, 365–372 (2017).

Topal, B. et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. Oncol. 14, 655–662 (2013).

Keck, T. et al. Pancreatogastrostomy Versus Pancreatojejunostomy for RECOnstruction After PANCreatoduodenectomy (RECOPANC, DRKS 00000767): perioperative and long-term results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 263, 440–449 (2016).

Cheng, Y. et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9, CD012257 (2017).

Shrikhande, S. V. et al. Pancreatic anastomosis after pancreatoduodenectomy: a position statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 161, 1221–1234 (2017).

Dong, Z., Xu, J., Wang, Z. & Petrov, M. S. Stents for the prevention of pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6, CD008914 (2016).

Diener, M. K. et al. Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 377, 1514–1522 (2011).

Montorsi, M. et al. Efficacy of an absorbable fibrin sealant patch (TachoSil) after distal pancreatectomy: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 256, 853–859; discussion 859–860 (2012).

Weniger, M. et al. Autologous but not fibrin sealant patches for stump coverage reduce clinically relevant pancreatic fistula in distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 40, 2771–2781 (2016).

Hassenpflug, M. et al. Teres ligament patch reduces relevant morbidity after distal pancreatectomy (the DISCOVER randomized controlled trial). Ann. Surg. 264, 723–730 (2016).

Hackert, T. et al. Sphincter of Oddi botulinum toxin injection to prevent pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Surgery 161, 1444–1450 (2017).

Gurusamy, K. S., Koti, R., Fusai, G. & Davidson, B. R. Somatostatin analogues for pancreatic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, CD008370 (2013).

Allen, P. J. et al. Pasireotide for postoperative pancreatic fistula. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 2014–2022 (2014).

Elliott, I. A. et al. Pasireotide does not prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula: a prospective study. HPB 20, 418–422 (2018).

Jeekel, J. No abdominal drainage after Whipple’s procedure. Br. J. Surg. 79, 182 (1992).

Conlon, K. C. et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial of the value of intraperitoneal drainage after pancreatic resection. Ann. Surg. 234, 487–493 (2001).

Van Buren, G. 2nd et al. A randomized prospective multicenter trial of pancreaticoduodenectomy with and without routine intraperitoneal drainage. Ann. Surg. 259, 605–612 (2014).

Van Buren, G. 2nd et al. A prospective randomized multicenter trial of distal pancreatectomy with and without routine intraperitoneal drainage. Ann. Surg. 266, 421–431 (2017).

Witzigmann, H. et al. No need for routine drainage after pancreatic head resection: the dual-center, randomized, controlled PANDRA trial (ISRCTN04937707). Ann. Surg. 264, 528–537 (2016).

Huttner, F. J. et al. Meta-analysis of prophylactic abdominal drainage in pancreatic surgery. Br. J. Surg. 104, 660–668 (2017).

McMillan, M. T. et al. Risk-adjusted outcomes of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy: a model for performance evaluation. Ann. Surg. 264, 344–352 (2016).

Mungroop, T. H. et al. Alternative fistula risk score for pancreatoduodenectomy (a-FRS): design and international external validation. Ann. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002620 (2017).

Welsch, T. et al. Persisting elevation of C-reactive protein after pancreatic resections can indicate developing inflammatory complications. Surgery 143, 20–28 (2008).

Ven Fong, Z. et al. Early drain removal — the middle ground between the drain versus no drain debate in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective validation study. Ann. Surg. 262, 378–383 (2015).

Khalsa, B. S. et al. Evolution in the treatment of delayed postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: surgery to interventional radiology. Pancreas 44, 953–958 (2015).

Wolk, S. et al. Management of clinically relevant postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) over two decades — a comparative study of 1 450 consecutive patients undergoing pancreatic resection. Pancreatology 17, 943–950 (2017).

Joseph, B. et al. Relationship between hospital volume, system clinical resources, and mortality in pancreatic resection. J. Am. College Surgeons 208, 520–527 (2009).

Birkmeyer, J. D. et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1128–1137 (2002).

Finks, J. F., Osborne, N. H. & Birkmeyer, J. D. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2128–2137 (2011).

Ghaferi, A. A., Birkmeyer, J. D. & Dimick, J. B. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1368–1375 (2009).

van Hilst, J. et al. Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma (DIPLOMA): a pan-european propensity score matched study. Ann. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002561 (2017).

Raoof, M. et al. Propensity score-matched comparison of oncological outcomes between laparoscopic and open distal pancreatic resection. Br. J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10747 (2018).

Nassour, I. et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: a propensity-matched study from a national cohort of patients. Ann. Surg. 268, 151–157 (2017).

Coolsen, M. M. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery after pancreatic surgery with particular emphasis on pancreaticoduodenectomies. World J. Surg. 37, 1909–1918 (2013).

Lassen, K. et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: ERAS recommendations. Clin. Nutr. 32, 870–871 (2013).

Lee, G. C. et al. High performing whipple patients: factors associated with short length of stay after open pancreaticoduodenectomy. J. Gastrointestinal Surg. 18, 1760–1769 (2014).

de Rooij, T. et al. Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy (LEOPARD): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 18, 166 (2017).

de Rooij, T. et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy (LEOPARD-2): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 19, 1 (2018).

Bassi, C. et al. Influence of surgical resection and post-operative complications on survival following adjuvant treatment for pancreatic cancer in the ESPAC-1 randomized controlled trial. Digestive Surg. 22, 353–363 (2005).

Merkow, R. P. et al. Postoperative complications reduce adjuvant chemotherapy use in resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 260, 372–377 (2014).

Valle, J. W. et al. Optimal duration and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: ongoing lessons from the ESPAC-3 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 504–512 (2014).

Tol, J. A. et al. Definition of a standard lymphadenectomy in surgery for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a consensus statement by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 156, 591–600 (2014).

Dasari, B. V. et al. Extended versus standard lymphadenectomy for pancreatic head cancer: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Gastrointestinal Surg. 19, 1725–1732 (2015).

Warschkow, R. et al. The more the better — lower rate of stage migration and better survival in patients with retrieval of 20 or more regional lymph nodes in pancreatic cancer: a population-based propensity score matched and trend SEER analysis. Pancreas 46, 648–657 (2017).

Strobel, O. et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: number of positive nodes allows to distinguish several N categories. Ann. Surg. 261, 961–969 (2015).

Tarantino, I. et al. Staging of pancreatic cancer based on the number of positive lymph nodes. Br. J. Surg. 104, 608–618 (2017).

Chun, Y. S., Pawlik, T. M. & Vauthey, J. N. 8th edn of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Pancreas and Hepatobiliary Cancers. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25, 845–847 (2018).

Verbeke, C. S. et al. Redefining the R1 resection in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Surg. 93, 1232–1237 (2006).

Esposito, I. et al. Most pancreatic cancer resections are R1 resections. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 15, 1651–1660 (2008).

Campbell, F. et al. Classification of R1 resections for pancreatic cancer: the prognostic relevance of tumour involvement within 1 mm of a resection margin. Histopathology 55, 277–283 (2009).

Chandrasegaram, M. D. et al. Meta-analysis of radical resection rates and margin assessment in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Surg. 102, 1459–1472 (2015).

Strobel, O. et al. Pancreatic cancer surgery: the new R-status counts. Ann. Surg. 265, 565–573 (2017).

Hank, T. et al. Validation of at least 1 mm as cut-off for resection margins for pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the body and tail. Br. J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10842 (2018).

Ghaneh, P. et al. The impact of positive resection margins on survival and recurrence following resection and adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002557 (2017).

Barreto, S. G. & Windsor, J. A. Justifying vein resection with pancreatoduodenectomy. Lancet Oncol. 17, e118–e124 (2016).

Isaji, S. et al. International consensus on definition and criteria of borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma 2017. Pancreatology 18, 2–11 (2018).

Khorana, A. A. et al. Potentially curable pancreatic cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 2324–2328 (2017).

Seufferlein, T. et al. [S3-guideline exocrine pancreatic cancer]. Zeitschrift Gastroenterol. 51, 1395–1440 (2013).

Tempero, M. A. et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 15, 1028–1061 (2017).

Jang, J. Y. et al. Oncological benefits of neoadjuvant chemoradiation with gemcitabine versus upfront surgery in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter phase 2/3 trial. Ann. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002705 (2018).

Michelakos, T. et al. Predictors of resectability and survival in patients with borderline and locally advanced pancreatic cancer who underwent neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX. Ann. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002600 (2017).

Sanjay, P., Takaori, K., Govil, S., Shrikhande, S. V. & Windsor, J. A. ‘Artery-first’ approaches to pancreatoduodenectomy. Br. J. Surg. 99, 1027–1035 (2012).

Ironside, N. et al. Meta-analysis of an artery-first approach versus standard pancreatoduodenectomy on perioperative outcomes and survival. Br. J. Surg. 105, 628–636 (2018).

Hackert, T., Werner, J., Weitz, J., Schmidt, J. & Buchler, M. W. Uncinate process first—a novel approach for pancreatic head resection. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 395, 1161–1164 (2010).

Hartwig, W. et al. Extended pancreatectomy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: definition and consensus of the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 156, 1–14 (2014).

Conroy, T. et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1817–1825 (2011).

Hartwig, W. et al. Outcomes after extended pancreatectomy in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Surg. 103, 1683–1694 (2016).

Murakami, Y. et al. Portal or superior mesenteric vein resection in pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic head carcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 102, 837–846 (2015).

Kalser, M. H. & Ellenberg, S. S. Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch. Surg. 120, 899–903 (1985).

Klinkenbijl, J. H. et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann. Surg. 230, 776–782; discussion 782–774 (1999).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 358, 1576–1585 (2001).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1200–1210 (2004).

Oettle, H. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine versus observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297, 267–277 (2007).

Regine, W. F. et al. Fluorouracil versus gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299, 1019–1026 (2008).

Regine, W. F. et al. Fluorouracil-based chemoradiation with either gemcitabine or fluorouracil chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: 5-year analysis of the U. S. Intergroup/RTOG 9704 phase III trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 18, 1319–1326 (2011).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid versus observation for pancreatic cancer: composite data from the ESPAC-1 and -3(v1) trials. Br. J. Cancer 100, 246–250 (2009).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid versus gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 304, 1073–1081 (2010).

Schmidt, J. et al. Open-label, multicenter, randomized phase III trial of adjuvant chemoradiation plus interferon Alfa-2b versus fluorouracil and folinic acid for patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 4077–4083 (2012).

Sinn, M. et al. CONKO-005: adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus erlotinib versus gemcitabine alone in patients after R0 resection of pancreatic cancer: a multicenter randomized phase iii trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 3330–3337 (2017).

Conroy, T. et al. Unicancer GI PRODIGE 24/CCTG PA.6 trial: a multicenter international randomized phase III trial of adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine (gem) in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas [abstract]. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, LBA4001 (2018).

Mokdad, A. A. et al. Neoadjuvant therapy followed by resection versus upfront resection for resectable pancreatic cancer: a propensity score matched analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 515–522 (2017).

de Geus, S. W. et al. Neoadjuvant therapy versus upfront surgery for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a nationwide propensity score matched analysis. Surgery 161, 592–601 (2017).

Strobel, O. & Buchler, M. W. Pancreatic cancer: clinical practice guidelines — what is the evidence? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13, 593–594 (2016).

Versteijne, E. et al. Meta-analysis comparing upfront surgery with neoadjuvant treatment in patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Surg. 105, 946–958 (2018).

Van Tienhoven, G. e. a. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (PREOPANC-1): a randomized, controlled, multicenter phase III trial [abstract]. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, LBA4002 (2018).

Mollberg, N. et al. Arterial resection during pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 254, 882–893 (2011).

Von Hoff, D. D. et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 1691–1703 (2013).

Suker, M. et al. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and patient-level meta-analysis. Lancet. Oncol. 17, 801–810 (2016).

Strobel, O. et al. Resection after neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced, “unresectable” pancreatic cancer. Surgery 152, S33–S42 (2012).

Hackert, T. et al. The TRIANGLE operation — radical surgery after neoadjuvant treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer: a single arm observational study. HPB 19, 1001–1007 (2017).

Strobel, O. et al. Re-resection for isolated local recurrence of pancreatic cancer is feasible, safe, and associated with encouraging survival. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 20, 964–972 (2013).

Hou, S. et al. Advanced development of primary pancreatic organoid tumor models for high-throughput phenotypic drug screening. SLAS Discov. 23, 574–584 (2018).

Tiriac, H. et al. Organoid profiling identifies common responders to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 8, 1112–1129 (2018).

NewLink Genetics Corporation. NewLink Genetics Announces Results from Phase 3 IMPRESS Trial of Algenpantucel-L for Patients with Resected Pancreatic Cancer. GlobeNewswire https://globenewswire.com/news-release/2016/05/09/837878/0/en/NewLink-Genetics-Announces-Results-from-Phase-3-IMPRESS-Trial-of-Algenpantucel-L-for-Patients-with-Resected-Pancreatic-Cancer.html (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.S., J.N. and M.W.B. researched data for this article. All authors made a substantial contribution to discussions of content, writing the manuscript and reviewing and/or editing the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Strobel, O., Neoptolemos, J., Jäger, D. et al. Optimizing the outcomes of pancreatic cancer surgery. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 16, 11–26 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-018-0112-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-018-0112-1

This article is cited by

-

Modulating ferroptosis sensitivity: environmental and cellular targets within the tumor microenvironment

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2024)

-

NUSAP1 promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression by drives the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and reduces AMPK phosphorylation

BMC Cancer (2024)

-

Radiological classification of the Heidelberg triangle and its application in laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for malignancies

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2024)

-

FBXO31 is upregulated by METTL3 to promote pancreatic cancer progression via regulating SIRT2 ubiquitination and degradation

Cell Death & Disease (2024)

-

MicroRNA-130b Suppresses Malignant Behaviours and Inhibits the Activation of the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway by Targeting MET in Pancreatic Cancer

Biochemical Genetics (2024)