Abstract

Pandemics have become more frequent and more complex during the twenty-first century. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following pandemics is a significant public health concern. We sought to provide a reliable estimate of the worldwide prevalence of PTSD after large-scale pandemics as well as associated risk factors, by a systematic review and meta-analysis. We systematically searched the MedLine, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CNKI, WanFang, medRxiv, and bioRxiv databases to identify studies that were published from the inception up to August 23, 2020, and reported the prevalence of PTSD after pandemics including sudden acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1, Poliomyelitis, Ebola, Zika, Nipah, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), H5N1, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A total of 88 studies were included in the analysis, with 77 having prevalence information and 70 having risk factors information. The overall pooled prevalence of post-pandemic PTSD across all populations was 22.6% (95% confidence interval (CI): 19.9–25.4%, I2: 99.7%). Healthcare workers had the highest prevalence of PTSD (26.9%; 95% CI: 20.3–33.6%), followed by infected cases (23.8%: 16.6–31.0%), and the general public (19.3%: 15.3–23.2%). However, the heterogeneity of study findings indicates that results should be interpreted cautiously. Risk factors including individual, family, and societal factors, pandemic-related factors, and specific factors in healthcare workers and patients for post-pandemic PTSD were summarized and discussed in this systematic review. Long-term monitoring and early interventions should be implemented to improve post-pandemic mental health and long-term recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The explosive spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak around the world within a very short period of time once again brought public attention to infectious disease pandemics. Since 2000, with rapid changes and increases in urbanization and global travel, infectious disease pandemics have become more frequent and more complex, notable examples of which are Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), Nipah, influenza A subtype H5N1, and Zika [1]. The SARS pandemic of 2003 was the first global public health emergency in the twenty-first century, which was followed shortly by the H5N1 outbreak of 2005–2006. Since then, the World Health Organization has declared another five Public Health Emergencies of International Concern: H1N1 influenza virus pandemic (2009), resurgence of wild poliovirus (2014), West Africa Ebola virus outbreak (2014), Zika virus outbreak (2018), and COVID-19 (2020) [2, 3]. Large-scale pandemics can significantly increase global morbidity and mortality and result in severe economic, social, and political disruption [4]. Moreover, a major infectious disease pandemic may have widespread and pervasive detrimental effects on individuals’ mental health [5, 6]. For example, a sudden disease outbreak that is associated with high infectivity and rapid transmission results in fear, distress, and anxiety in the public [7,8,9]. Long-term stress and anxiety that are caused by a pandemic may further induce symptoms of depression [10, 11]. This ongoing exposure to danger, illness, death, disaster situations, stigma, and discrimination during a pandemic can induce an acute stress response and even cause posttraumatic stress reactions [5, 12,13,14].

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common, serious, and complex mental disorder that occurs following exposure to traumatic events. It is characterized by intrusion and reexperiencing the trauma through flashback-like dissociative reactions, efforts to avoid trauma-related thoughts, feelings, places, or people, persistent negative cognition and mood, and hyperarousal, such as anxiety, sleep difficulties, and irritability [15]. Failed recovery from PTSD can have long-term harmful effects on an individual’s social function, family life, and personal health [16].

Numerous studies have investigated the prevalence of PTSD after pandemics. However, controversy exists with regard to the prevalence and pattern of PTSD (e.g., PTSD with acute onset or delayed onset) after such infectious disease outbreaks. The prevalence of PTSD that has been reported in epidemiological studies has varied widely, depending on the particular outbreak, target population, and methods that are used to assess the disorder. Such prevalence estimates range from 2.3 to 55.1% [17, 18]. For example, a study in 2006 evaluated post-SARS PTSD among SARS survivors and found that the rate of PTSD 3 and 12 months after the patients’ discharge was 46.2% and 38.8%, respectively [19]. Jalloh et al. [20] assessed the mental health impact of the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemics on the general population in affected countries and found that 76.4% of the general public showed any symptom of PTSD, 27% met the level of clinical concern for PTSD, and 16% met the level of a probable diagnosis of PTSD. A recent survey on posttraumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among residents in the hardest-hit areas in China indicated a prevalence of 7% [21]. Although epidemiological data on PTSD are growing, the global prevalence of PTSD and its drivers in individuals after pandemics remain largely unknown.

With the spread of COVID-19 pandemic, the global estimate of burden of PTSD following pandemic is vital for the development of intervention and management strategy. However, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis has reported the pooled prevalence of PTSD after infectious disease pandemics and potential risk factors. Such information would help guide public health responses, medical resource allocation, and health policy planning in anticipation of and during such worldwide public health emergencies. The present systematic review sought to provide a reliable estimate of the worldwide prevalence of infectious disease pandemic-related PTSD and investigate the effects of demographic characteristics, clinical stage, and other factors on such prevalence.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [22]. We systematically searched the MedLine, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CNKI, WanFang, medRxiv, and bioRxiv databases to identify studies that were published from the inception up to August 23, 2020, that reported the prevalence of PTSD after infectious disease pandemics, including SARS, H1N1, poliomyelitis, Ebola, Zika, Nipah, MERS-CoV, H5N1, and COVID-19, as well as risk factors contributing to PTSD. The search terms that were used to search the titles and abstracts are listed in the Appendix. We also scanned reference lists and review articles for additional studies that might meet the inclusion criteria.

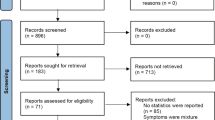

Two authors, YMG and L. Liu, independently assessed the articles for their eligibility for inclusion. Studies were included if they were longitudinal or cross-sectional studies regarding infectious disease pandemics, including SARS, H1N1, poliomyelitis, Ebola, Zika, Nipah, MERS-CoV, H5N1, and COVID-19 and met any of following criteria: (1) peer-reviewed articles without language restriction that reported the prevalence of PTSD after these pandemics using a wide range of PTSD measurement tools, including international diagnostic criteria, actual medical records, and standard questionnaires or instruments; (2) peer-reviewed articles that analyzed the influential factors for high-risk of post-pandemic PTSD. The following types of articles were excluded: case reports, reviews, and dissertations. If the same sample was used in more than one publication, only the data set with the most comprehensive information was included to avoid data duplication in the meta-analysis. The process of identifying eligible studies and reasons for exclusion are presented in Fig. 1.

The following information was extracted from each study according to a prespecified protocol: (1) first author, (2) publication year, (3) region of research, (4) type of infectious outbreak, (5) time of survey relative to the end of pandemic, (6) PTSD assessment instrument, (7) study population, (8) sample size, (9) PTSD prevalence (Table 1), and (10) risk factors for PTSD. Only baseline data within 12 months after pandemics from longitudinal studies were included when calculating overall prevalence. These data were independently extracted from eligible papers by five of the authors (YMG, SST, L. Liu, YJW, AYZ, and XXL) and subsequently double-checked by two other authors (YMG and YJW). Quality assessments of eligible studies were conducted independently by two of the authors (YMG and YJW) using the 11-item Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for cross-sectional studies [23] and 9-star Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies [24]. Studies with eight or more stars on the AHRQ and NOS were determined to be high quality. All discrepancies were resolved by group discussion and consensus.

Data analysis

All of the analyses were calculated using the statistical packages for meta-analysis in Stata 12 software. Given the potential clinical and methodological heterogeneities, a random effects model was used to allow for a more conservative approach to calculate pooled prevalence estimates. Pooled prevalence estimates are expressed as mean estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used an I2 statistic estimate of ≥ 50% as an indicator of large statistical heterogeneity. To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroups and meta-regression analyses were conducted when possible using the following variables: population type (patients/infected survivors, healthcare workers, and general public), time of the survey relative to the start of the pandemic (within 6 months vs. over 6 months), gender (male and female), diagnostic methods (clinical diagnosis and scales), income level of countries (high-income vs. low- and middle-income countries based on the World Bank standard) [25], type of infectious disease (SARS, H1N1, Poliomyelitis, Ebola, Zika, Nipah, MERS-CoV, H5N1, and COVID-19), quarantine experience, and frontline work experience. Visual examinations of funnel plots, Begg’s test, and Egger’s test were used to assess the possibility of publication bias and small-study effects. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to identify the influence of individual studies on the pooled estimates by excluding each of the studies from the pooled estimate.

Results

A total of 1238 papers were initially retrieved (Fig. 1). After screening, 659 were excluded based on the title and abstract, 202 were excluded because they were duplicate studies, 81 were excluded because they were reviews and systematic reviews, and 18 were excluded because they were case reports and academic dissertations. After screening, 278 articles remained to be reviewed of the full-text for eligibility. Of these articles, 190 were excluded because they did not focus on the post-pandemic prevalence or risk factors of PTSD, leaving a total of 88 eligible studies included in the meta-analysis. Among these, 77 included prevalence information [18,19,20,21, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] and 70 included risk factor information [8, 20, 21, 26, 29,30,31,32, 34,35,36,37,38,39, 42, 43, 47, 49,50,51, 53,54,55,56,57,58, 60,61,62, 64,65,66,67, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79, 81, 83,84,85,86,87,88, 90, 91, 92, 93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108].

Post-pandemic PTSD prevalence

Of the 77 studies that included prevalence data, three major populations were analyzed and described, including 28 studies (24,815 participants) of healthcare workers, 14 studies (2161 participants) of infected patients, and 38 studies (176,855 participants) of the general public. Twenty-three studies (29.9%) focused on SARS, 47 (61.0%) on COVID-19, 3 (3.9%) on Ebola, 2 (2.6%) on MERS, 1 (1.3%) on H1N1, and 1 on multiple diseases including SARS, H5N1, and H1N1. Seventy studies (90.9%) used questionnaires to identify PTSD, and 7 studies (9.1%) made a PTSD diagnosis by professional mental health workers. As not all eligible studies reported gender information, quarantine exposure, or frontline experiences, we only identified 11 studies (14.3%) in gender subgroup analysis, 13 (16.9%) in quarantine subgroup analysis, and 14 (18.2%) in frontline healthcare workers subgroup analysis. In the quality assessment of the 88 eligible articles, 49 (55.7%) scored 8–10 points, 37 (42.0%) scored 6–7 points, and 2 (2.3%) scored 5 points. The main problems with study quality were generally associated with the following: no indication of whether evaluators of subjective components of the study were masked to other aspects of the status of the participants and lack of information about any patient exclusions.

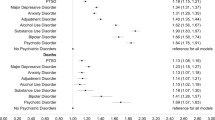

Almost all of the eligible studies evaluated the prevalence of PTSD within 12 months after the infectious outbreak, with the exception of four studies which included the prevalence at 30, 36, 41.4, 46 months, respectively [39, 46, 58, 85]. The estimated prevalence of PTSD after the pandemics was 22.6% (95% CI: 19.9–25.4%, I2: 99.7%). We conducted subgroup analyses based on the different populations and found that the prevalence of post-pandemic PTSD in healthcare workers, infected patients, and the general public was 26.9% (95% CI: 20.3%–33.6%), 23.8% (95% CI: 16.6%–31.0%), and 19.3% (95% CI: 15.3%–23.2%), respectively (Fig. 2). Further subgroup analyses were conducted and stratified by different population type, assuming there was a sufficient number of eligible studies for each clinical feature.

Subgroup analyses were performed with regard to the time of PTSD assessment after the infectious outbreak, gender, quarantine experience, diagnostic method, type of infectious outbreak, and frontline experience (Fig. 3). We did not find significant difference between the pooled prevalence of PTSD more than 6 months after infectious outbreak (21.1%; 95% CI: 15.7–26.6%) and that of within 6 months after infectious outbreak (22.5%; 95% CI: 19.6–25.4%). However, there were different time patterns in prevalence observed among the three populations, though no statistical difference was observed (p = 0.947). The PTSD prevalence in infected patients more than 6 months after the pandemic (28.8%; 95% CI: 14.7–42.8%) was higher than that within 6 months after the pandemic (18.6%; 95% CI: 12.0–25.2%). However, among healthcare workers and the general public, the PTSD prevalence more than 6 months after the pandemic (10%, 95% CI: 5.7%–14.4%; 12.4%, 3.6%–21.3%, respectively) was lower than within 6 months after the pandemic (28.6%, 95% CI: 21.4%–35.8%; 19.4%, 15.2%–23.5%, respectively).

The pooled prevalence of PTSD in males and females after infectious disease outbreak was 26.2% (95% CI: 9.3%–43%) and 27.2% (95% CI: 15.4%–39.1%), respectively (p = 0.916). Individuals with quarantine exposure during the pandemic had higher prevalence of PTSD (combined: 15.2%, 95% CI: 10.2–20.3%; healthcare workers: 17.0%, 95% CI: 5.5–28.5%; general public: 16.6%, 95% CI: 10.7–22.5%) than the individuals without quarantine experience (combined: 4.7%, 95% CI: 3.0–6.4%; healthcare workers: 4.0%, 95% CI: 1.8–6.2%; general public: 5.7%, 95% CI: 3.1–8.3%), though the differences were not significant (p = 0.162). Among healthcare workers, the pooled post-pandemic prevalence of PTSD in frontline was 30.8% (95% CI: 16.2–45.4%), which was higher than in non-frontline workers (8.2%, 95% CI: 0.6–15.9%) (p = 0.051).

When dividing eligible studies in terms of diagnostic methods, there was no difference of pooled post-pandemic prevalence of PTSD between studies diagnosed by a professional’s clinical standard (21.5%, 95% CI: 12.3–30.8%) and studies using self-reported scales or questionnaire (22.6%, 95% CI: 19.8–25.4%) (p = 0.935). The subgroup PTSD prevalence was 23.8% (95% CI: 13.2–34.4%) in patients and 8.9% (95% CI: 1.5–16.4%) in healthcare workers by clinical diagnosis, and 24.1% (95% CI: 15.0–33.2%) and 26.9% (95% CI: 20.5–33.4%) by questionnaire. All the studies with general public participants were assessed by scales with the estimated PTSD prevalence of 19.1% (95% CI: 15.2–23.0%). The estimated post-pandemic prevalence of PTSD overall in high-income regions and combined low- and middle-income regions was 24.6% (95% CI: 18.2%–31.1%) and 21.2% (95% CI: 18.3%–24.1%), respectively. The combined prevalence of PTSD during the COVID-19, SARS, and other epidemics (Ebola, MERS, and H1N1) was 24.6% (95% CI: 21.1%–28.1%), 19.9% (95% CI: 16.3%–23.4%), and 13.7% (95% CI: 5.5%–21.9%), respectively. There was no difference between subgroups among different income levels (p = 0.492) and pandemic types (p = 0.999).

Begg’s and Egger’s tests indicated no apparent publication bias (Fig. 4). A sensitivity analysis that excluded each study individually provided similar estimates of PTSD prevalence, suggesting that no single study included in the meta-analysis was likely to have an inordinate impact on the reported prevalence estimates.

Risk factors for post-pandemic PTSD

Seventy eligible studies reported risk factors for PTSD. However, because of the considerable heterogeneity and limited number of studies for each risk factor, only a systematic review but not a meta-analysis was conducted. We categorized predisposing factors for higher risk of post-pandemic PTSD into three groups: personal, family, or societal factors; infectious-related factors; and factors specific to subgroups. In terms of personal, family, or societal factors, individuals who are female [21, 31, 32, 34, 35, 39, 51, 57, 58, 65,66,67, 75, 76, 83, 86, 88, 90, 94, 97, 99, 100, 103, 104, 107], younger [32, 43, 66, 69, 73,74,75, 87, 101, 103], with low annual income [38, 69] and low level of education [67, 90, 97, 103] had higher risk of suffering from post-pandemic PTSD. Those who lived in a city [43] and previous or current tobacco users [67, 71] were also at greater risk. Poor psychological status including higher levels of anxiety and depression [43, 51, 91, 99], poor sleep quality [21, 76, 79], high stress levels [8, 49, 51], low levels of distress tolerance [55], neurotic and psychopathic personality [70, 78], and any other psychiatric disorder or history [31, 35, 50, 58, 61, 67, 69, 73, 84, 107] all were associated with higher risk of PTSD. In addition to these aspects of an individual’s psychological status, personal physical comorbidities [30, 39, 58, 67, 71] and PTSD symptoms among their family members were also associated with more risk [75]. Encountering traumatic events [51, 99, 107] before the outbreak also put an individual at higher risk of developing post-pandemic PTSD, especially when individuals utilized inappropriate coping strategies when dealing with the adverse events [36, 60, 62, 70,71,72,73, 83, 96]. Family and societal factors included low family/social support level [8, 47, 55, 74, 94, 97, 107], having or living with children [43, 56, 67, 94, 103], and limited living space [34, 103].

Some pandemic-related factors were associated with increased risk of developing PTSD. Quarantine or the experience of social isolation due to pandemic [26, 34, 38, 64, 66, 69, 75] was a major risk factor for post-pandemic PTSD, along with poor social life [47, 108], economic loss [34, 77, 93, 101], and impact on livelihood [34, 36, 66, 78]. In addition, having high risk or perception of high risk of contracting infection was also associated with greater risk of post-pandemic PTSD. This included being suspected or confirmed to be infected [35, 37, 69, 86], knowing relatives/friends/acquaintances infected/hospitalized/died due to the infection [20, 32, 35, 38, 39, 42, 66, 69, 71, 76, 85,86,87, 103], having family/friends with more exposure to the infection [103], perceiving there was a high risk/threat of contracting infection [20, 34, 42, 43, 54, 57, 60, 69, 76,77,78,79, 85, 86, 98, 103, 106, 108], and exposure to excessive negative information about the infection [42, 67]. Negative psychological responses to the infection, including feeling anxious/depressed [61, 99, 108], stressful [47, 53, 66, 70], extremely fearful and helpless [47, 55, 71, 79, 86], and any other negative feelings [81], during the pandemic were all risk factors for post-pandemic PTSD. Other pandemic-related factors that increased PTSD risk included individuals having uncertainty of the possibility of contracting infection [32] and those who felt stigmatized because of the pandemic [77].

Some risk factors were specific to healthcare workers and some to patients. Among healthcare workers, nurses [29, 71, 74], frontline workers [8, 53, 65, 95, 105, 108], those working in high-risk community [57], technicians [8], general practitioners [65], nonlocal aid workers supporting the highest-hit areas [92], were all groups at higher risk of developing post-pandemic PTSD. Healthcare workers who had less working experience [8, 49, 74, 91, 108], low job satisfaction [83], and longer work shifts [74, 92] were at more risk. Feeling fearful of potential harm, death, and life out of control due to the pandemic [102], having a colleague infected/hospitalized/in quarantine/deceased [65, 91], and having concerns that a person the healthcare worker lived with may be infected [57] were also associated with healthcare workers being at higher risk. As for infected patients, some clinical factors including higher disease severity [56], low level of SaO2 during hospitalization [84], feelings of discrimination [56, 61], and death of family members from infection [56] were major risk factors for PTSD development. Box 1 summarizes the categorized risk factors determined by our systematic review.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that specifically focused on the pooled estimate of prevalence of PTSD after large-scale infectious disease outbreaks, including COVID-19 pandemic, as well as risk factors contributing to higher post-pandemic PTSD. A number of meta-analyses and systematic reviews of PTSD have been conducted after natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes [109, 110], and other significant traumatic events, such as the World Trade Center disaster in 2001 [111]. The combined prevalence of PTSD after infectious disease pandemics that was found in the present study (23%) was even higher than the estimated pooled prevalence after other disasters, such as major traumatic events (~20%) [112] and floods (~16%) [110]. Our results indicate that PTSD is common in individuals who experience infectious diseases outbreaks, which may persist over a relatively long period of time. Confirmed cases of infection, frontline healthcare workers, and quarantined individuals tend to be vulnerable populations who have a higher potential of developing post-pandemic PTSD. We reviewed and categorized the numerous potential risk factors for post-pandemic PTSD and these findings indicate that early screening and timely evidence-based interventions and social support should be applied to potentially mitigate post-pandemic PTSD and related psychological problems during COVID-19 and future pandemics.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, PTSD has a variable course. Acute stress disorder can be present in the initial month after a traumatic event, after which only a proportion of these people will subsequently develop PTSD [113]. In addition, a small proportion of people can develop delayed PTSD with the onset of the disorder occurring at least 6 months after the traumatic event [114]. Recent work shows that many cases of delayed-onset PTSD actually reflect worsening of symptoms over time as a result of stressors that occur after the traumatic event [115]. We performed a subgroup analysis using 6 months as the dividing time point. We observed that the pooled prevalence of PTSD within 6 months and after 6 months was both stable at a high level (about 20%), though there was an increasing trend of the post-pandemic prevalence of PTSD among patients (≤6 months: 19%; >6 months: 29%). One study included in our meta-analysis even reported that the prevalence of PTSD among SARS survivors over 46 months was high at about 40% [39]. The reasons for this high and essentially stable prevalence over 4 years might involve the following: (1) PTSD is an enduring and pervasive mental disorder for many patients [116], and (2) the median recovery time may extend for years, especially in those who experience trauma directly. Long-term and sustained PTSD emphasizes the need for attention and continuous follow-up and studies of suitable interventions and the mechanisms by which this occurs. We could not perform the subgroup analysis over a time period longer than 1 year because of the limited number of studies that had sufficiently long assessment periods. More longitudinal studies with longer follow-up times are clearly needed.

Previous studies suggested that the female gender may be a significant risk factor for developing PTSD [58, 86, 117]. Moreover, PTSD persists for a longer period of time in females than in males [39]. However, in the present meta-analysis, there was no significant difference of the post-pandemic prevalence of PTSD between females (27%) and males (26%). This might be partially accounted for by a higher family burden of the males and being more concerned about family members, which may compromise their mental health status [74]. Furthermore, more frequent risky behaviors during epidemics (e.g., going to crowded places or less likely to wear masks) and the resulting higher infective rate [118, 119] might also contribute to the similar prevalence of PTSD between females and males. These findings have important implications for the clinical practice and policymakers that both genders are equally susceptible to PTSD within the context of infectious diseases.

Healthcare workers generally face enormous physical and mental pressures from a higher likelihood of burnout from overwork and being infected, the anxiety and distress that are associated with isolation, instinctive fear and frustration during work, and feeling stigmatized and rejected in their neighborhoods because of their hospital work [26, 30, 120]. Based on this analysis, healthcare workers had a higher trend of overall prevalence of PTSD and PTSD prevalence within 6 months after the pandemic (27% and 29%, respectively) compared with the general public (both 19%). Besides, the pooled prevalence of post-pandemic PTSD was 31% among frontline healthcare workers and 8% among non-frontline healthcare workers. It suggested a much greater stress that is experienced by frontline healthcare workers and correspondingly greater need for proper preventive care and interventions for their mental health. Frontline nurses also deserve particular attention. Of 28 included investigations about post-pandemic PTSD prevalence among healthcare workers, 6 studies [29, 49, 60, 68, 81, 83] focused particularly on frontline nurses and found a high prevalence of PTSD, which indicates relative vulnerability of this group to develop post-pandemic PTSD. Uncomfortable working environments including the long-term use of personal protective equipment, intense and often overloaded work intensity of an extended duration because of severe pandemic conditions, a lack of understanding and specific drugs to fight the disease, and unavoidable psychological shock that is caused by the demise of infected patients all contribute to the high prevalence of PTSD among both frontline healthcare workers and frontline nurses. Another specific group of healthcare workers worth particular attention was those who worked on the frontline and who contacted the infection and became patients. Frontline healthcare workers are at very high risk of exposure to infection and are in very high potential risk to be infected. Once they become vectors of the virus and unaware of it, they will subsequently transmit it to their patients and colleagues through close contact. Therefore, frontline healthcare workers who became patients may not only feel fearful, stressful, lonely as other patients do, they may also be likely to feel guilty because they are unsure whether there are more victims because of them [8, 19, 28].

Quarantine is one of the major public health measures that is intended to prevent the further spread of an infectious disease, which has been shown to effectively contain a pandemic outbreak. However, the psychological impact of quarantine, including feelings of uncertainty, exhaustion, insomnia, and detachment from others, is wide ranging, long lasting, and substantial [121]. Moreover, evidence shows that the duration of quarantine is significantly associated with greater PTSD symptoms [38]. In the present meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of post-pandemic PTSD among pandemic victims who had experience with quarantine during the outbreak (15%) was higher than that among victims without quarantine experience (5%), though there was no statistical difference. Furthermore, quarantine was also associated with other negative mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia [66, 69]. To maximize the benefits of quarantine and minimize its negative impacts, policymakers are encouraged to keep the duration of quarantine as short as possible, give quarantined individuals as much necessary information as possible, provide adequate supplies, reduce boredom, improve communications, and ensure that quarantined people understand the reasons for and implications of quarantine [121]. What is more, digital support including online health monitoring systems and online social platforms is particularly necessary during this period [122].

Previous studies have suggested that the annual income may be one of the important factors involved in mental disorders, and those with lower income levels were more likely to have depression, anxiety, insomnia, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts [69, 123]. However, there was no significant difference of the post-pandemic PTSD prevalence between high-income regions (24.6%) and the low- to middle-income regions (21.2%) in our analysis. This might be partially accounted for by a lack of studies in low- to middle-income region studies (e.g., Ebola). Moreover, the majority of high-income region studies were drawn from SARS experiences in Taiwan and Hong Kong, which compromises the representativeness and generalizability of these data. These findings remind us that post-pandemic PTSD is a severe problem across all regions and populations. Hence, more investigations in different areas around the world using formal clinical diagnosis rather than self-rating questionnaires are encouraged to provide us with more accurate information as to post-pandemic PTSD prevalence and risk factors.

Most studies have suggested that age was another major demographic factor that contributes to higher risk of post-pandemic PTSD, although in our review, different studies had inconsistent conclusions regarding which age group was more likely to be PTSD victims. Through our review, those having children, married/widowed/divorced, working in business units, and encountering economic difficulties due to the infections are at high risk of developing PTSD [34, 39, 43, 56, 67, 73, 77, 90, 93, 94, 101, 103]. It suggests that the living conditions, responsibility, or source of stress at a given age are the “culprit” of individuals’ PTSD post-pandemic. Another risk factor worth our attention is perceived stigmatization or discrimination due to the pandemic [56, 61, 77]. Infected patients are not only the vectors of infection, but also often the victim of social stigma following the infection. Healthcare workers can also experience social stigmatization since they work directly with infected patients. As many studies have demonstrated a close relationship between stigmatization and psychiatric morbidities (e.g. [41, 46, 61]), there is a great need to enhance publicity and education of the harm of stigmatization to reduce the process of social stigmatization and its impact as well as to deploy psychological interventions for those perceiving stigmatization.

The significance of this study lies in the application of the present meta-analytic strategy, the inclusion of major large-scale twenty-first century pandemics, and the use of a relatively large sample to evaluate the combined post-pandemic prevalence of PTSD. Equally informative part was the use of subgroup analyses that identified several risk factors for post-pandemic PTSD, including being infected survivors, the female gender, frontline medical and nursing staff, and having experience with quarantine during pandemic outbreaks. We also found that PTSD symptoms persisted over a relatively long period of time. These findings demonstrate that the burden of PTSD among infected survivors, frontline medical and nursing staff, and quarantined individuals is substantial and pervasive. Furthermore, 61% eligible studies in this meta-analysis focused on COVID-19, reflecting the great attention paid by all over the world toward this serious pandemic. This study sought to inform us about prevalence and risk factors that might be particularly salient for our understanding of the development of post-pandemic PTSD. Appropriate monitoring, timely interventions, social support, and long-term follow-up should be applied to mitigate post-pandemic PTSD and related psychological disturbances, particularly in high-risk populations. Our findings are also underscored by a large population study from the USA which found that having a psychiatric disorder in the preceding 12 months was a risk factor of contracting COVID-19 [124]. Our study indicated that as COVID-19 continues, addressing mental health may also be an important public health strategy for reducing transmission of the virus and promoting social and economic development [125].

This study has several potential limitations. First, the number of studies that performed longitudinal assessments was relatively small, and the time window of these studies was relatively short. Second, although we initially searched for all major large-scale pandemics since 2000, only 6 out of 77 eligible studies that focused on the prevalence of PTSD in pandemics (Ebola, MERS, and H1N1) other than SARS and COVID-19 were identified and analyzed. Third, we observed substantial heterogeneity in the estimates of PTSD prevalence across studies. The causes of this heterogeneity might be partly explained by geographical distribution, variability among different populations, measurement differences, and between-study differences in population characteristics, but the remaining unexplained heterogeneity was still substantial (I2 > 50%). However, given so many variables and responses to the trauma made by the public during each pandemic, clinical heterogeneity may not be surprising as the PTSD prevalence after a pandemic might not be a singular clinically meaningful entity. Finally, there were insufficient data to allow subgroup comparisons that could be stratified by other variables that are likely associated with PTSD, such as age and comorbidities.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the combined prevalence of PTSD in individuals after infectious disease pandemics exceeded one-fifth, with the highest prevalence observed in healthcare workers, followed by infected patients and the general public. Our findings indicate that post-pandemic PTSD is a significant public health concern after infectious disease pandemics, including COVID-19. The PTSD should be paid attention to by policymakers all over the world because of the substantial burden in population regardless of the different sex, gender, geographical coverage, income levels, etc. Public health strategy involving mental health response is warranted, especially in the area of post-pandemic and even after long-term recovery period. Early detection and early interventions should be implemented comprehensively and extensively, especially for vulnerable populations, including infected survivors, frontline medical and nursing staff, and individuals with quarantine experience, to improve post-pandemic mental health and recovery in the long-term. More longitudinal studies with longer follow-up times after COVID-19 are needed.

References

Bedford J, Farrar J, Ihekweazu C, Kang G, Koopmans M, Nkengasong J. A new twenty-first century science for effective epidemic response. Nature. 2019;575:130–6.

Giesecke J. The truth about PHEICs. Lancet. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31566-1.

Lupia T, Scabini S, Mornese Pinna S, Di Perri G, De Rosa FG, Corcione S. 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak: a new challenge. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:22–7.

Madhav N, Oppenheim B, Gallivan M, Mulembakani P, Rubin E, Wolfe N. Pandemics: risks, impacts, and mitigation. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1/pt5.ch17.

Terhakopian A, Benedek DM. Hospital disaster preparedness: mental and behavioral health interventions for infectious disease outbreaks and bioterrorism incidents. Am J Disaster Med. 2007;2:43–50.

Fasina OF, Jonah GE, Pam V, Milaneschi Y, Gostoli S, Rafanelli C. Psychosocial effects associated with highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) in Nigeria. Vet Ital. 2010;46:459–65.

Bonanno GA, Ho SAY, Chan JCK, Kwong RSY, Cheung CKY, Wong CPY, et al. Psychological resilience and dysfunction among hospitalized survivors of the SARS epidemic in Hong kong: a latent class approach. Health Psychol. 2008;27:659–67.

Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:127–33.

Sim M. Psychological trauma of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome victims and bereaved families. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016054.

Elizarrarás-Rivas J, Vargas-Mendoza JE, Mayoral-García M, Matadamas-Zarate C, Elizarrarás-Cruz A, Taylor M, et al. Psychological response of family members of patients hospitalised for influenza A/H1N1 in Oaxaca, Mexico. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:104.

Keita MM, Taverne B, Sy Savane S, March L, Doukoure M, Sow MS, et al. Depressive symptoms among survivors of Ebola virus disease in Conakry (Guinea): preliminary results of the PostEboGui cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:127.

Wilson DJ. Psychological trauma and its treatment in the polio epidemics. Bull Hist Med. 2008;82:848–77.

Rabelo I, Lee V, Fallah MP, Massaquoi M, Evlampidou I, Crestani R, et al. Psychological distress among Ebola survivors discharged from an Ebola treatment unit in Monrovia, Liberia—a qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2016;4:142.

Jakovljevic M, Bjedov S, Jaksic N, Jakovljevic I. COVID-19 pandemia and public and global mental health from the perspective of global health securit. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32:6–14.

Shalev A, Liberzon I, Marmar C. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2459–69.

Kirkpatrick HA, Heller GM. Post-traumatic stress disorder: theory and treatment update. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2014;47:337–46.

Zhang KR, Xu Y, Yang H, Liu Z, Wang Y, Li S, et al. Investigation by comparison on the posttraumatic stress response among SARS patients, hospital staffs and the public exposed to SARS. Chin J Behav Med Sci. 2006;15:358–60.

Tian YJ, Zhang YL, Qian ZL. Investigation on the emotional status of villagers in a rural area of Hangzhou after the implementation of closure measures during the prevention and control of 2019-nCoV infection. Health Res. 2020;40:16–8+21.

Gao H, Hui W, Lan X. A follow-up study of post-traumatic stress disorder of SARS patients after discharge. Chinese J Rehabilitation Med. 2006;21:1003–4+1026.

Jalloh MF, Li W, Bunnell RE, Ethier KA, O’Leary A, Hageman KM, et al. Impact of Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on mental health in Sierra Leone, July 2015. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e000471.

Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Rostom. A, Dubé. C, Cranney. A celiac disease. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analysis. 2000. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1055–7.

Berthelot N, Lemieux R, Garon-Bissonnette J, Drouin-Maziade C, Martel E, Maziade M. Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:848–55.

Chan AO, Huak CY. Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med. 2004;54:190–6.

Chen CS, Wu HY, Yang PC, Yen CF. Psychological distress of nurses in Taiwan who worked during the outbreak of SARS. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:76–9.

Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJH, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–65.

Fekih-Romdhane F, Ghrissi F, Abbassi B, Cherif W, Cheour M. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a Tunisian community sample. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113131.

Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. The enemy which sealed the world: effects of COVID-19 diffusion on the psychological state of the Italian population. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1–14.

Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D’Aniello GE, Stramba Badiale C, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684.

González Ramírez LP, Martínez Arriaga RJ, Hernández-Gonzalez MA, De la Roca-Chiapas JM. Psychological distress and signs of post-traumatic stress in response to the COVID-19 health emergency in a mexican sample. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:589–97.

González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos M, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:172–6.

Guo J, Feng XL, Wang XH, van Ijzendoorn MH. Coping with COVID-19: exposure to covid-19 and negative impact on livelihood predict elevated mental health problems in Chinese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–18.

Guo Q, Zheng Y, Shi J, Wang J, Li G, Li C, et al. Immediate psychological distress in quarantined patients with COVID-19 and its association with peripheral inflammation: a mixed-method study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:17–27.

Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1206–12.

Hong X, Currier GW, Zhao X, Jiang Y, Zhou W, Wei J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in convalescent severe acute respiratory syndrome patients: a 4-year follow-up study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:546–54.

Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD, Ren AK, Zhou XP. Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19. Chin J Industr Hyg Occup Dis. 2020;38:192–5.

Hugo M, Declerck H, Fitzpatrick F, Severy N, Gbabai OB, Dercroo T, et al. Post-traumatic stress reactions in Ebola virus disease survivors in Sierra Leone. Emerg Med. 2015;5;285.

Joseph R, Alshayban D, Lucca JM, Alshehry YA. The immediate psychological response of the general population in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.19.20135533.

Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Murphy J, McBride O, Ben‐Ezra M, Bentall RP, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and associated comorbidity during the covid‐19 pandemic in ireland: a population‐based study. J Trauma Stress. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22565.

Keita MM, Doukouré M, Chantereau I, Sako FB, Traoré FA, Soumaoro K, et al. Survivors of epidemic recent disease Ebola virus in psychiatric hospital service national Donka in Guinea: psychopathological and psychotherapeutic study. Evol Psychiatr. 2017;82:127–42.

Kwek S-K, Chew W-M, Ong K-C, Ng AW-K, Lee LS-U, Kaw G, et al. Quality of life and psychological status in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome at 3 months postdischarge. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:513–9.

Lam MH, Wing YK, Yu MW, Leung CM, Ma RC, Kong AP, et al. Mental morbidities and chronic fatigue in severe acute respiratory syndrome survivors: long-term follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2142–7.

Lau JTF, Yang X, Pang E, Tsui HY, Wong E, Yun KW. SARS-related perceptions in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:417–24.

Um DH, Kim JS, Lee HW, Lee SH. Psychological effects on medical doctors from the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak: a comparison of whether they worked at the MERS occurred hospital or not, and whether they participated in mers diagnosis and treatment. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2017;56:28–34.

Leng M, Wei L, Shi X, Cao G, Wei Y, Xu H, et al. Mental distress and influencing factors in nurses caring for patients with COVID-19. Nurs Crit Care. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12528.

Li Q. Psychosocial and coping responses towards 2019 coronavirus diseases (COVID-19): a cross-sectional study within the Chinese general population. QJM. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa226.

Li Y, Wang Y, Jiang J, Valdimarsdottir UA, Fall K, Fang F, et al. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Med. 2020:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720001555.

Liang L, Ren H, Cao R, Hu Y, Qin Z, Li C, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91:841–52.

Lin CY, Peng YC, Wu YH, Chang J, Chan CH, Yang DY. The psychological effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on emergency department staff. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:12–7.

Lin L-Y, Wang J, Ou-Yang X-Y, Miao Q, Chen R, Liang F-X, et al. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018.

Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, Hahm H. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113172.

Liu D, Baumeister RF, Veilleux JC, Chen C, Liu W, Yue Y, et al. Risk factors associated with mental illness in hospital discharged patients infected with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113297.

Luceño-Moreno L, Talavera-Velasco B, García-Albuerne Y, Martín-García J. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17;5514.

Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MG, Ho SC, Chan VL. Risk factors for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in SARS survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:590–8.

Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Poletti S, Vai B, Bollettini I, et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.037.

Nie A, Su X, Zhang S, Guan W, Li J. Psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on frontline nurses: a cross-sectional survey study. J Clin Nurs. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15454.

Park HY, Park WB, Lee SH, Kim JL, Lee JJ, Lee H, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression of survivors 12 months after the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:605.

Qi R, Chen W, Liu S, Thompson PM, Zhang LJ, Xia F, et al. Psychological morbidities and fatigue in patients with confirmed COVID-19 during disease outbreak: prevalence and associated biopsychosocial risk factors. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.08.20031666.

Ren Y, Zhou Y, Qian W, Li Z, Liu Z, Wang R, et al. Letter to the Editor “A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China”. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:132–3.

Reynolds DL, Garay JR, Deamond SL, Moran MK, Gold W, Styra R. Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:997–1007.

Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Di Lorenzo G, Di Marco A, Siracusano A, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2010185.

Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, Mensi S, Niolu C, Pacitti F, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. An N=18147 web-based survey. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.09.20057802.

Seyahi E, Poyraz BC, Sut N, Akdogan S, Hamuryudan V. The psychological state and changes in the routine of the patients with rheumatic diseases during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Turkey: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:1229–38.

Shahrour G, Dardas LA. Acute stress disorder, coping self-efficacy, and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID-19. J Nurs Manag. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13124.

Shi L, Lu Z-A, Que J-Y, Huang X-L, Liu L, Ran M-S, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in china during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2014053.

Shi TY, Jiang C, Jia SH, Liu QG, Zhang J, Qi XY. Post-traumatic stress disorder and related factors following the severe acute respiratory syndrome. Chin J Clin Rehabilit. 2005;9:9–13.

Si M-Y, Su X-Y, Jiang Y, Wang W-J, Gu X-F, Ma L, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:113.

Sim K, Chan YH, Chong PN, Chua HC, Soon SW. Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:195–202.

Sim K, Chong PN, Chan YH, Soon WS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related psychiatric and posttraumatic morbidities and coping responses in medical staff within a primary health care setting in Singapore. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1120–7.

Song X, Fu W, Liu X, Luo Z, Wang R, Zhou N, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:60–5.

Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:105–10.

Sun L, Sun Z, Wu L, Zhu Z, Zhang F, Shang Z, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of acute posttraumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.06.20032425.

Sun S, Goldberg SB, Lin D, Qiao S, Operario D. Psychiatric symptoms, risk, and protective factors among university students in quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.03.20144931.

Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, Jiang L, Jiang X, Zhang L, et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:84–92.

Tang W, Hu T, Hu B, Jin C, Wang G, Xie C, et al. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:1–7.

Tham KY, Tan YH, Loh OH, Tan WL, Ong MK, Tang HK. Psychiatric morbidity among emergency department doctors and nurses after the SARS outbreak. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2004;33 5 Suppl:S78–9.

Su T, Yin J, Su Y, Tsai S, Lien T, Yang C, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: a prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:119–30.

Wang Y, Duan Z, Peng K, Li D, Ou J, Wilson A, et al. Acute stress disorder among frontline health professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak: a structural equation modelling investigation. Psychosom Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000851.

Wang YX, Guo HT, Du XW, Song W, Lu C, Hao WN. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder of nurses exposed to corona virus disease 2019 in China. Medicine. 2020;99:e20965.

Wu KK, Chan SK, Ma TM. Posttraumatic stress after SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1297–300.

Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:302–11.

Xu J, Zheng Y, Wang M, Zhao J, Zhan Q, Fu M, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress in Chinese university students during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:Ph60–4.

Yan F, Dun Z, Li S. Survey on mental status of subjects recovered from SARS. Chin Ment Health J. 2004;18:675–7.

Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, Ni X, Deng X, Jia Y, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27:384–95.

Zhao Y, An Y, Tan X, Li X. Mental health and its influencing factors among self-isolating ordinary citizens during the beginning epidemic of covid-19. J Loss Trauma. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1761592.

Feng Z, Liu X, Chen Z. Characteristics of mental health problems among general public during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Southwest Univ Social Sci Ed. 2020;46:109–15.

Leng F. Relationship between anxiety, depression and PTSD among frontline nurses fighting against COVID-19: a correlation analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2020;19:14–7.

Li C, Mi Y, Chu J, Zhu L, Zhang Z, Liang L, et al. Investigation and analysis of PTSD among front-line nursing staff fighting COVID-19. J Nurs Train. 2020;35:615–8.

Wei Y, Meng XD, Ni YX. The investigation of anxiety and PTSD of populations in community and factors analysis during the pandemic of COVID-19. Pract J Clin Med. 2020;17:267–70.

Xu CY, Huang DM, Wang WJ, Wu P, Guo M, Qiu HL. Investigation and analysis of psychological state with in the ordinary people, the medical staff with different medical positions and different regions in Hainan Province under the novel corona-virus pneumonia epidemic. Chin J Health Psychol. 2020;28:1356–61.

Yang LQ, Wu XQ, Zhang Y, Li M, Liu GX, Gao YL, et al. Mental health status of medical staffs fighting SARS: a long-dated investigation. Chin J Health Psychol. 2007;15:567–9.

Zhang KR, Xu Y, Yang H, Liu ZG, Che ZQ, Wang YQ, et al. Investigation by comparison on the posttraumatic stress response among SARS patients, hospital staffs and the public exposed to SARS. Chin J Behav Med Sci. 2006;15:358–60.

Zhang Y, Zhuang LY, Yang W. Investigating PTSD symptoms among secondary school students during the new canopy epidemic-A case study of Shude Middle School in Chengdu, China. Educ Sci Forum. 2020;17:45–8.

Lee TM, Chi I, Chung LW, Chou KL. Ageing and psychological response during the post-SARS period. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:303–11.

Arpacioglu S, Gurler M, Cakiroglu S. Secondary traumatization outcomes and associated factors among the health care workers exposed to the COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020940742.

Ausín B, González-Sanguino C, Castellanos MÁ, Muñoz M. Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of covid-19 in Spain. J Gend Stud. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2020.1799768.

García-Fernández L, Romero-Ferreiro V, López-Roldán PD, Padilla S, Rodriguez-Jimenez R. Mental health in elderly spanish people in times of COVID-19 outbreak. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.027.

Ho SMY, Kwong-Lo RSY, Mak CWY, Wong JS. Fear of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) among health care workers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:344–9.

Jiang H-J, Nan J, Lv Z-Y, Yang J. Psychological impacts of the COVID-19 epidemic on Chinese people: exposure, post-traumatic stress symptom, and emotion regulation. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2020;13:252–9.

Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:233–40.

Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho A-R, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;87:123–7.

McAlonan GM, Lee AM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Tsang KWT, Sham PC, et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:241–7.

Plomecka MB, Gobbi S, Neckels R, Radziński P, Skórko B, Lazerri S, et al. Mental Health Impact of COVID-19: a global study of risk and resilience factors. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.05.20092023.

Styra R, Hawryluck L, Robinson S, Kasapinovic S, Fones C, Gold WL. Impact on health care workers employed in high-risk areas during the Toronto SARS outbreak. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:177–83.

Beaglehole B, Mulder RT, Frampton CM, Boden JM, Newton-Howes G, Bell CJ. Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:716–22.

Chen L, Liu A. The incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder after floods: a meta-analysis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015;9:329–33.

Liu B, Tarigan LH, Bromet EJ, Kim H. World Trade Center disaster exposure-related probable posttraumatic stress disorder among responders and civilians: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101491.

Utzon-Frank N, Breinegaard N, Bertelsen M, Borritz M, Eller NH, Nordentoft M, et al. Occurrence of delayed-onset post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40:215–29.

Bryant RA, Friedman MJ, Spiegel D, Ursano R, Strain J. A review of acute stress disorder in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:802–17.

Santiago PN, Ursano RJ, Gray CL, Pynoos RS, Spiegel D, Lewis-Fernandez R, et al. A systematic review of PTSD prevalence and trajectories in DSM-5 defined trauma exposed populations: intentional and non-intentional traumatic events. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59236.

Galatzer-Levy IR, Huang SH, Bonanno GA. Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: a review and statistical evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:41–55.

Bisson JI, Cosgrove S, Lewis C, Robert NP. Post-traumatic stress disorder. BMJ. 2015;351:h6161.

Lee YK, Lee HS, Cho A, Yoon JW, Jeon HJ, Noh JW, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder of hemodialysis patients with MERS-CoV exposure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:iii699–700.

Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, et al. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:577–83.

Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, Li WT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1745–52.

Conversano C, Marchi L, Miniati M. Psychological distress among healthcare professionals involved in the COVID-19 emergency: vulnerability and resilience factors. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17:94–6.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–20.

Caetano R, Silva AB, Guedes A, Paiva CCN, Ribeiro GDR, Santos DL, et al. Challenges and opportunities for telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: ideas on spaces and initiatives in the Brazilian context. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36:e00088920.

Hong J, Knapp M, McGuire A. Income-related inequalities in the prevalence of depression and suicidal behaviour: a 10-year trend following economic crisis. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:40–4.

Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30462-4.

Sun YK, Bao YP, Ravindran A, Sun Y, Shi J, Lu L. Mental health challenges raised by rapid socioeconomic transformations in China: lessons learned and prevention strategies. Heart Mind. 2020;4:59–66.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81761128036, 81821092, and 31900805), Special Research Fund of PKUHSC for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. BMU2020HKYZX008), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2019YFA0706200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KY, YMG, L. Liu, and YKS contributed equally to this article. L. Lu, JS, YPB, and KY proposed the topic and main idea. YMG and L. Liu were responsible for the literature search and study selection. YMG, SST, L. Liu, YJW, AYZ, and XXL were responsible for the data extraction and quality assessment. YMG wrote the initial draft. KY, YMG, L. Liu, YKS, XL, SZS, LS, WY, SF, MVV, RAB, XYZ, MSR, JS, YPB, and L. Lu commented on and revised the paper. L. Lu, JS, and YPB made the final version. All authors contributed to the final draft of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, K., Gong, YM., Liu, L. et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Mol Psychiatry 26, 4982–4998 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01036-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01036-x

This article is cited by

-

Socio-economic factors associated with post-traumatic stress symptoms among adolescents and young people during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

PTSS in COVID-19 survivors peritraumatic stress symptoms among COVID-19 survivors in Iraq

Current Psychology (2024)

-

Psychosocial interventions for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: rapid review and meta-analysis

Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (2024)

-

The Essential Network (TEN): engagement and mental health insights from a digital mental health assessment tool for Australian health professionals during COVID-19

BMC Digital Health (2023)

-

Symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder and their relationship with the fear of COVID−19 and COVID−19 burden among health care workers after the full liberalization of COVID−19 prevention and control policy in China: a cross-sectional study

BMC Psychiatry (2023)