Key Points

-

Measles remains a leading vaccine-preventable cause of child mortality in Africa and Asia, and continues to cause outbreaks in industrialized countries.

-

Remarkable progress in reducing measles incidence and mortality has been made in resource-poor countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, as a consequence of increasing measles vaccine coverage and provision of a second opportunity for measles vaccination through supplementary immunization activities.

-

Measles virus (MV) is highly infectious, requiring a high level of population immunity to interrupt transmission, and might be more difficult to eliminate in regions of high population density and high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection.

-

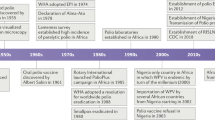

The global elimination of measles has been debated since the 1960's, shortly after measles vaccines were first licensed.

-

Criteria necessary for disease eradication include: first, humans must be required for virus transmission; second, sensitive and specific diagnostic tools must exist; and finally an effective intervention must be available. Measles is thought by many experts to meet all of these criteria

-

Measles vaccines are safe, effective and have interrupted MV transmission in large geographic areas, providing a suitable tool for global measles elimination.

-

The ideal measles vaccine would be inexpensive, safe, heat-stable, immunogenic in neonates or very young infants, administered as a single dose without needle or syringe, and would not prime individuals for atypical measles or be associated with prolonged immunosuppression. Several vaccine candidates with some of these characteristics are undergoing development.

-

A significant challenge to global measles elimination efforts will be to maintain the resources, political will and public confidence to implement measles vaccination and surveillance programmes.

Abstract

Measles remains a leading vaccine-preventable cause of child mortality worldwide, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where almost half of the estimated 454,000 measles deaths in 2004 occurred. However, great progress in measles control has been made in resource-poor countries through accelerated measles-control efforts. The global elimination of measles has been debated since measles vaccines were first licensed in the 1960's, and this debate is likely to be renewed if polio virus is eradicated. This review discusses the pathogenesis of measles and the likelihood of the worldwide elimination of this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

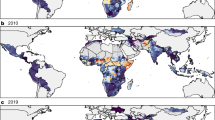

Measles, which is caused by the measles virus (MV) (Box 1), was estimated to cause 454,000 deaths in 2004, almost half of which were in sub-Saharan Africa, and continues to cause outbreaks in communities with low vaccination coverage in industrialized nations1 (Fig. 1). It is one of the most important infectious diseases of humans and has caused millions of deaths since its emergence thousands of years ago. The disease is characterized by a prodromal illness of fever, cough, coryza and conjunctivitis followed by the appearance of a generalized maculopapular rash. Deaths from measles are mainly due to an increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial and viral infections, which is attributed to a prolonged state of MV-induced immune suppression (Box 2).

MV most closely resembles rinderpest virus, a pathogen of cattle, and might have evolved as a zoonotic infection from an ancestral virus that was present in communities in which cattle and humans lived in close proximity. MV is thought to have become established in human populations approximately 5,000 years ago, when human populations achieved sufficient size in the Middle Eastern river valley civilizations to maintain virus transmission. The virus was introduced into the Americas in the sixteenth century as a result of European exploration of the New World, resulting in thousands of deaths in native Amerindian populations. Deaths in this susceptible native American population due to measles and smallpox facilitated the European conquest of the Americas2. MV was first isolated from the blood of David Edmonston in 1954 by John Enders and Thomas Peebles3. The development of vaccines against measles soon followed4.

Pathogenesis of MV infection

Respiratory droplets from infected persons function as vehicles of transmission by delivering infectious virus to epithelial cells of the respiratory tract of susceptible hosts. During the 10–14 day incubation period between infection and the onset of clinical signs and symptoms, MV replicates and spreads in the infected host (Fig. 2). Initial viral replication occurs in epithelial cells at the entry site in the upper respiratory tract, and the virus then spreads to local lymphatic tissue. Replication in local lymph nodes is followed by viraemia and the dissemination of MV to many organs, including lymph nodes, skin, kidney, gastrointestinal tract and liver, in which the virus replicates in the epithelial and endothelial cells, and in lymphocytes, monocytes and macrophages.

Panels summarize features of the basic pathogenesis of measles-virus infection. a | Panel shows the spread of the virus through the body from the initial site of infection in respiratory epithelia to the skin, in which the diagnostic rash is formed. Sites of infection are overlaid with virus titre (pfu). b | Illustrates the appearance of clinical symptoms over time, including the diagnostic Koplik's spots and rash. c | Panel summarizes immune responses over time, including both B- and T-cell responses. Clinical symptoms arise coincident with the onset of the immune response. Pfu; plaque-forming unit. Modified with permission from Ref. 87 © (2001) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Host immune responses (Fig. 2) to MV are essential for viral clearance, clinical recovery and the establishment of long-term immunity. Early innate immune responses occur during the prodromal phase and include activation of natural killer (NK) cells and increased production of interferons (IFN)-α and β. The adaptive immune responses consist of MV-specific humoral and cellular responses. The protective efficacy of antibodies to MV is shown by the immunity conferred to infants from passively acquired maternal antibodies and the protection of exposed, susceptible individuals following post-exposure administration of anti-MV immune globulin5. The most abundant and rapidly produced antibodies are against the nucleoprotein (N). Antibodies to the haemagglutinin (H) and fusion (F) proteins contribute to virus neutralization and are sufficient to provide protection.

Evidence for the importance of cellular immunity to MV is demonstrated by the ability of children with agammaglobulinaemia to fully recover from measles, whereas children with severe defects in T-lymphocyte function often develop severe or fatal disease6. Monkeys depleted of CD8+ T-lymphocytes and challenged with wild-type MV had a more extensive rash, higher levels of MV in the blood and a longer duration of viraemia than control animals7. CD4+ T-lymphocytes are activated in response to MV infection and secrete cytokines capable of directing humoral and cellular immune responses. Plasma cytokine profiles show increased levels of IFN-γ during the acute phase, followed by a shift to high levels of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10 during convalescence8. The initial predominant T-helper-1 (Th1)-response is essential for viral clearance, and the later Th2 response promotes the development of protective MV-specific antibodies.

The immune responses induced by MV infection are paradoxically associated with depressed responses to non-MV antigens, and this effect continues for several weeks to months after resolution of the acute illness. Following MV infection, delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses to recall antigens, such as tuberculin, are suppressed9 and cellular and humoral responses to new antigens are impaired10. This MV-induced immune suppression renders individuals more susceptible to secondary bacterial and viral infections that can cause pneumonia and diarrhoea, and is responsible for much of the measles-related morbidity and mortality11,12. Pneumonia, the most common fatal complication of measles, occurs in 56–86% of measles-related deaths13.

Abnormalities of both the innate and adaptive immune responses have been described following MV infection. Transient lymphopaenia with a reduction in CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes occurs in children with measles. Functional abnormalities of immune cells have also been detected, including decreased lymphocyte proliferative responses14. Dendritic cells that are infected with MV in vitro mature poorly, lose the ability to stimulate responses in lymphocytes and undergo cell death15. The dominant Th2-response in children recovering from measles can inhibit Th1 responses and increase susceptibility to intracellular pathogens16,17. The production of IL-12, which is important for the generation of the Th1-type immune response, is decreased in vitro following binding of CD46 (Ref. 18), an MV receptor, and is reduced for several weeks in children with measles19. Conversely, IL-10 production is elevated for several weeks in the plasma of children with measles8. IL-10 downregulates the synthesis of cytokines, suppresses macrophage activation and T-cell proliferation and inhibits DTH responses.

Progress in measles control

Prior to the development and widespread use of measles vaccines, measles was estimated to result in 5–8 million deaths annually. The decline in mortality from measles in developed countries was associated with economic development, improved nutritional status and supportive care, and antibiotic therapy for secondary bacterial pneumonia. Remarkable progress in reducing measles incidence and mortality has been made in resource-poor countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa20, as a consequence of increasing measles vaccine coverage, provision of a second opportunity for measles vaccination through supplementary immunization activities, and efforts by the WHO, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and their partners to target 45 countries for accelerated and sustained measles mortality reduction21. Provision of vitamin A through polio and measles vaccination campaigns has contributed further to the reduction in measles mortality1. In 2003, the World Health Assembly endorsed a resolution urging member countries to reduce the number of deaths attributed to measles by 50% by the end of 2005 compared with the estimated number of measles-related deaths in 1999, a target that is likely to have been met. Overall global measles mortality in 2004 was estimated to be 454,000 deaths (uncertainty over exact numbers means that this estimate could range from 329,000 to 596,000 deaths), a 48% decrease from the measles-related deaths recorded in 1999 (Ref. 22).

Measles eradication

The global elimination of measles has been debated since the 1960's, shortly after measles vaccines were first licensed23. The Dahlem Conference on Disease Eradication (1997) defined eradication as the permanent reduction to zero of the global incidence of infection caused by a specific pathogen as a result of deliberate efforts, with the consequence that interventions would no longer be necessary. Although modifications to this definition were subsequently proposed, three criteria were deemed necessary for a disease to be considered eradicable: first, humans must be crucial for transmission; second, sensitive and specific diagnostic tools must exist; and finally, an effective intervention must be available. Demonstration of the interruption of transmission in a large geographic area for a prolonged period further supports the feasibility of eradication. Measles is thought by many experts to meet these criteria for eradication24,25.

Biological feasibility of measles elimination

MV has no non-human reservoirs, can be readily diagnosed after the onset of a rash and has not mutated or evolved to significantly alter immunogenic epitopes. However, MV is highly infectious, requiring a high level of population immunity to interrupt transmission, is contagious for several days prior to the onset of the rash (the first easily diagnosed symptom), and might be more difficult to eliminate in regions that have a high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1).

Non-human reservoirs. Humans are the only reservoir for MV. Non-human primates can be infected with MV and develop an illness similar to measles in humans. However, populations of wild primates are not of a sufficient size to maintain MV transmission. To provide a sufficient number of new susceptible individuals through births to maintain MV transmission, a population size of several hundred thousand individuals with 5,000 to 10,000 births per year is required26.

Case detection. The characteristic clinical features of measles are of sufficient sensitivity and specificity to have a high predictive value in regions where measles is endemic. However, laboratory diagnosis is necessary if MV transmission rates are low or in immunocompromised persons who might not have the characteristic clinical manifestations (Box 2). Infection with rubella virus, parvovirus B19, human herpes virus 6 and dengue viruses all cause symptoms that can mimic those of measles. Detection of IgM antibodies to MV by enzyme immunoassay is the standard laboratory method for diagnosing acute measles27.

Subclinical measles is defined as a fourfold rise in MV-specific IgG antibodies following exposure to wild-type MV in an asymptomatic individual with some prior measles immunity. Subclinical infection might be important in boosting protective antibody levels in children with decreasing immunity28, but raises the concern that persons with incomplete immunity and subclinical infection might be capable of transmitting MV29. MV has been isolated from a naturally immune, asymptomatically re-infected individual30, and extensive epidemiological investigation of a person with measles in the Netherlands failed to identify a contact with clinically apparent measles, implying that transmission might have occurred from a person with subclinical infection31.

Viral evolution and diversity. Although RNA viruses have high mutation rates32, MV is an antigenically monotypic virus: the surface proteins that are responsible for inducing protective immunity have retained their antigenic structure across time and space. The public health significance of this is that measles vaccines developed decades ago from a single MV strain remain protective worldwide. However, variability in the genome is sufficient to allow for molecular epidemiologic investigation. One of the most variable regions of the MV genome is the 450-nucleotide sequence at the carboxyl terminus of the N protein, with up to 12% variability between wild-type viruses. The WHO recognizes 8 clades of MV (designated A to H) and 23 genotypes33,34. New genotypes will probably be identified with improved surveillance and molecular characterization. As measles-control efforts intensify, molecular surveillance of circulating MV strains could be used to document the interruption of MV transmission and to identify the source and transmission pathways of MV outbreaks35,36.

Infectiousness. MV is one of the most highly contagious infectious agents and outbreaks can occur in populations in which less than 10% of individuals are susceptible. The contagiousness of MV is best expressed by the basic reproductive number (Ro), which is the mean number of secondary cases that would arise if an infectious agent were introduced into a completely susceptible population. Ro is a function not only of the infectious agent but also of the host population. The estimated Ro for MV is generally assumed to be 12–18, in contrast to only 5–7 for smallpox virus and 2–3 for SARS coronavirus. In the 1951 measles epidemic in Greenland, the index case attended a community dance during the infectious period resulting in an Ro of 200 (Ref. 37). The high infectivity of MV implies that a high level of population immunity (approximately 95%) is required to interrupt MV transmission.

Further hindering elimination efforts is the fact that persons with measles are infectious during the prodromal phase, several days prior to the onset of rash, and therefore transmit the virus prior to clinical case detection. MV can be isolated in tissue culture from urine as late as one week after the onset of rash. Detection of MV in body fluids by various means, including identification of multinucleated giant cells in nasal secretions and the use of PCR after reverse transcription of RNA (RT-PCR), indicates the potential for prolonged infectious periods in persons immunocompromised by severe malnutrition or HIV-1 infection38,39. However, whether detection of MV by these methods indicates prolonged contagiousness is unclear, and prolonged transmission of MV is not likely to be a significant obstacle to eradication. In contrast to polioviruses40, transmission of the live attenuated measles vaccine virus has not been reported.

HIV-1 epidemic. In regions of high HIV-1 prevalence and crowding, such as urban centres in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV-1-infected children could have a role in the sustained transmission of MV41. HIV-1-infected mothers have defective transfer of IgG antibodies across the placenta, resulting in lower titres of protective antibodies in the infant, which increases the period of susceptibility to MV infection prior to routine immunization. HIV-1-infected children that are vaccinated against MV might become susceptible to MV owing to progressive HIV-1-induced immunosuppression. Children with defective cell-mediated immunity might not develop the characteristic measles rash, and infection might therefore go unrecognized, with the potential for widespread transmission of MV, particularly in healthcare settings. Finally, HIV-1-infected children might have impaired cell-mediated immune clearance and prolonged shedding of MV39, increasing the period of infectivity and the spread of MV to secondary contacts. However, even if HIV-1-infected children lose protective immunity over time, the high mortality rate of HIV-infected children, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where approximately one third of untreated HIV-1-infected children die by one year of age and half are dead by two years of age, is such that they do not live long enough for a sizeable pool of MV-susceptible children to accumulate42. This might change with increased access to antiretroviral drugs. Successful control of measles in the countries of southern Africa suggests that the HIV-1 epidemic is not a significant barrier to measles control20,43.

Technical feasibility of measles elimination

Measles vaccines are safe, effective and have interrupted MV transmission in large geographic areas, providing a crucial tool for global measles elimination.

Measles vaccines. Several attenuated measles vaccines are available worldwide, either as single-virus vaccines or in combination with other vaccine viruses (commonly rubella and mumps). Most of the currently used measles vaccines were derived from the Edmonston strain of MV isolated by Enders and Peebles in 1954. These vaccines have undergone different passage histories in cell culture, but nucleotide sequence analyses show genetic differences of less than 0.6% between most vaccine strains (Fig. 3).

Most attenuated measles vaccines were developed from the Edmonston strain of measles virus. The Edmonston B vaccine was the first licensed measles vaccine but was associated with a high frequency of fever and rash. The further attenuated Schwarz and Edmonston-Zagreb vaccines are widely used throughout the world, although the Moraten vaccine is the only measles vaccine used in the United States. Modified with permission from Ref. 88 (1993) WHO.

The measles vaccine induces both humoral and cellular immune responses. Antibodies first appear between 12 and 15 days after vaccination and peak at 21 to 28 days. IgG antibodies persist in the blood for years (Box 2). Vaccination also induces MV-specific cellular immune responses44. The proportion of children who develop protective antibody titres following measles vaccination depends on the presence of inhibitory maternal antibodies and the immunological maturity of the vaccine recipient, as well as the dose and strain of vaccine virus. Polymorphisms in human immune-response genes (for example, TAP2 and HLA-DQA1) also influence immune responses to measles vaccine45. Frequently cited statistics are that approximately 85% of children develop protective antibody titres when the measles vaccine is administered at 9 months of age, and 90–95% have a protective antibody response after vaccination at 12 months of age46. The duration of protective antibody titres following measles vaccination is more variable and shorter than that acquired through infection with wild-type MV, with an estimated 5% of children losing protective antibody titres 10–15 years after vaccination47. However, decreasing antibody titres do not necessarily imply a loss of protective immunity, as a secondary immune response usually develops after re-exposure to MV, with a rapid rise in IgG antibodies.

Limitations of licensed measles vaccines. Despite the public health benefits of measles vaccines, there are several limitations of the licensed vaccines that might be important for global measles elimination. First, attenuated measles vaccines are inactivated by light and heat, and lose about half of their potency after reconstitution if stored at 20°C for one hour and almost all potency if stored at 37°C for one hour. A cold chain must be maintained to support measles immunization activities. Second, measles vaccines must be injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly, necessitating trained healthcare workers, needles, syringes and the proper disposal of hazardous waste. Third, both maternally acquired antibodies and immunological immaturity reduce the protective efficacy of measles vaccination in early infancy, hindering effective immunization of young infants48. Fourth, the attenuated measles vaccine has the potential to cause serious outcomes, such as lung or brain infection, in severely immunocompromised persons49. Finally, as discussed below, a second opportunity for measles vaccination, in addition to the first dose through routine immunization services, must be provided to achieve high enough levels of population immunity to interrupt MV transmission.

Logistical feasibility of measles elimination

High levels of population immunity against measles, achieved through high measles-vaccine coverage, can interrupt MV transmission. Perhaps the main challenge to global measles-elimination efforts will be to maintain the resources, political will and public confidence to implement intensive measles vaccination and surveillance activities.

Measles elimination strategies. Measles elimination is the interruption of MV transmission in a defined geographical area. Small outbreaks of primary and secondary cases might still occur following importation from outside the region, but sustained transmission does not occur. Because of the high infectivity of MV and the fact that not all individuals develop protective immunity following vaccination, a single dose of measles vaccine does not achieve a sufficient level of population immunity to eliminate measles. A second opportunity for measles immunization is necessary to eliminate measles by providing protective immunity to children who failed to respond to the first dose and to those who were not previously vaccinated. Two broad strategies to administer the second dose have been used. In countries with sufficient infrastructure, the second dose of measles vaccine is administered through routine immunization services, typically prior to the start of school. High coverage levels are ensured by school entry requirements. A second approach, first developed by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) for South and Central America50, involves mass-immunization campaigns (called supplementary immunization activities, or SIAs) to deliver the second dose of measles vaccine. This strategy was successful in eliminating measles in Latin America, and has resulted in a marked reduction in measles incidence and mortality in parts of sub-Saharan Africa43.

The PAHO strategy consists of four sub-programmes: Catch-Up, Keep-Up, Follow-Up and Mop-Up50. The Catch-Up phase is a one-time, mass-immunization campaign that targets all children in a broad age group regardless of whether they previously had wild-type MV infection or measles vaccination. The goal is to rapidly achieve a high level of population immunity and interrupt MV transmission. If successful, SIA activities are cost effective51,52 and can abruptly interrupt MV transmission with dramatic declines in incidence and mortality. Keep-Up refers to the need to maintain >90% routine measles vaccine coverage through improved access to measles vaccination and a reduction in missed opportunities. Follow-Up refers to periodic mass campaigns to prevent the accumulation of susceptible children that typically target children 1–4 years of age, a narrower age group than targeted in Catch-Up campaigns. Mop-Up campaigns target children that are difficult to reach in sites of measles outbreaks or low vaccine coverage.

War, population movement and demographics. Polio vaccination campaigns have been successfully conducted during scheduled ceasefires in regions of conflict53. Similar results should be achievable for measles vaccination campaigns, although additional highly skilled healthcare workers are needed to administer parenteral measles vaccine compared with oral poliovirus vaccine. However, maintaining high levels of routine measles vaccine coverage in areas of conflict is extremely difficult, and devastating measles outbreaks frequently occur in refugee populations54. The ease of global travel facilitates the importation of MV into regions where measles has been successfully controlled (as exemplified by the 2006 measles outbreak in Boston, USA) and cross-border population movements necessitate regional rather than country level control strategies. Finally, measles control might be particularly difficult in the high-density slum areas of large cities in Africa and Asia, where several factors converge to facilitate MV transmission among susceptible persons, including high population density and difficulties in achieving high vaccination coverage.

Loss of public confidence. A loss of public confidence in vaccines can significantly impair elimination efforts, as demonstrated by the poliovirus outbreaks in northern Nigeria that spread across several continents after a loss of public confidence in polio vaccines55. Measles outbreaks have occurred in communities that are opposed to vaccination on religious or philosophical grounds56. Much public attention has focused on a purported association between the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism following the publication of a report in 1998 hypothesizing that the MMR vaccine might cause a syndrome of autism and intestinal inflammation57. The events that followed, and the public concern over the safety of the MMR vaccine, led to diminished vaccine coverage in the United Kingdom and provide important lessons in the misinterpretation of epidemiological evidence and the communication of scientific results to the public58. As a consequence, measles outbreaks became more frequent and larger in size59. Subsequently, several comprehensive reviews and epidemiological studies rejected evidence for a causal relationship between MMR vaccination and autism60,61.

New tools for measles eradication

Aerosol administration of measles vaccine was first evaluated in the early 1960s in several countries, including the former Soviet Union and the United States. More recent studies in South Africa62 and Mexico63 have shown that aerosol administration of measles vaccine is highly effective in boosting antibody titres, although the primary immune response to aerosolized measles vaccine is reduced compared with subcutaneous administration64. Administration of measles vaccine by aerosol has the potential to facilitate measles vaccination during mass campaigns, and the WHO plans to test and bring to licensure an aerosol measles vaccine by 2009.

The ideal measles vaccine would be inexpensive, safe, heat-stable, immunogenic in neonates or very young infants, and administered as a single dose without the need to use a needle or syringe. The age at vaccination should coincide with the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) schedule to maximize compliance and share resources. Finally, a new vaccine should not prime individuals for atypical measles on exposure of immunized individuals to wild-type MV (a complication of formalin-inactivated measles vaccines) and should not be associated with prolonged immunosuppression adversely affecting immune responses to subsequent infections (a complication of high-titre measles vaccines).

Several vaccine candidates with some of these characteristics are undergoing development and testing. Naked cDNA vaccines are thermostable, inexpensive and could theoretically elicit antibody responses in the presence of passively acquired maternal antibody. DNA vaccines encoding either or both of the measles H and F proteins are safe, immunogenic and protective against measles challenge in naive, juvenile rhesus macaque monkeys65. A different DNA vaccine, containing H, F and N genes and an IL-2 molecular adjuvant, provided protection to infant macaques in the presence of neutralizing antibody66,67. Alternative vectors for administering MV genes, such as alphavirus68, parainfluenza virus69 or enteric bacteria70 are also under investigation. Immune responses to intranasal administration of MV vaccines are enhanced by the use of adjuvants71. Novel oral immunization strategies have been developed using plant-based expression of the H protein from MV in tobacco72.

Prospects for global measles elimination

The elimination of measles in large areas, such as the Americas, suggests that global measles elimination is feasible with current vaccination strategies25,73,74. The American Red Cross, along with other partners, has played a significant role in establishing the Measles Initiative, which has been responsible for much of the success in measles control in Africa and is committed to reducing global measles deaths by providing measles vaccine to children. The key questions regarding global measles elimination are whether epidemiological conditions are sufficiently different in parts of Africa and Asia to hinder measles-elimination efforts, and whether there will be the political and public support necessary for elimination activities. Interruption of MV transmission could be difficult in densely populated urban environments of Africa and Asia and in regions of high HIV-1 prevalence24. Other potential obstacles to global measles elimination have been identified, including immunity that decreases over time, and the possibility of transmission from subclinical cases, although these have not hindered measles elimination in the Americas24,75. Measles outbreaks have occurred in susceptible adults, most notably the large outbreak in Sâo Paulo, Brazil, in 1997, but have not led to sustained endemic transmission24. Garnering the political will and public support is likely to be more difficult in resource-rich countries where the burden of disease due to measles is not recognized and unfounded fears of serious adverse events from vaccination are more prevalent. Whether the threat from bioterrorism precludes stopping measles vaccination after eradication is a topic of debate, but, at the least, a single-dose rather than a two-dose measles vaccination strategy could be adopted73.

The measles eradication end game is likely to be different from that for smallpox and polioviruses76,77. Higher levels of population immunity are necessary to interrupt MV transmission. Linking surveillance activities with rapid outbreak response and vaccination efforts will be crucial for measles elimination, as it is for smallpox and polio. However, the rapid spread of MV and the need for trained healthcare workers to administer measles vaccine will be additional obstacles. Ensuring that the necessary supply of measles vaccine is maintained as elimination efforts progress will also be crucial, requiring close collaboration with vaccine manufacturers.

Critics of eradication programmes claim that they divert resources from primary healthcare and are imposed on countries or communities from outside. Enormous resources and efforts might be required to eradicate the few remaining cases of disease, and the economic and social costs of eradication need to be considered78. The polio eradication campaign in Nigeria was seen to trigger a massive outbreak response for three confirmed cases in Adamawa State in 2005, whereas hundreds of deaths due to measles did not result in a comparable response79. But delays in achieving polio eradication will make many people hesitant to move forward with measles eradication. Serious discussion of measles eradication will probably take place after polio eradication is achieved, and will be a focus of intense debate in the years to come.

References

WHO. Progress in reducing measles mortality — worldwide 1999–2003. Wkly Epidemiol. Rec. 78–81 (2005).

McNeill, W. H. Plagues and Peoples. (Penguin, London,1976).

Enders, J. F. & Peebles, T. C. Propagation in tissue cultures of cytopathic agents from patients with measles. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 86, 277–286 (1954). The classic paper reporting the in vitro propagation of MV that eventually led to the development of measles vaccines.

Enders, J. F., Katz, S. L., Milovanovic, M.V. & Holloway, A. Studies on an attenuated measles-virus vaccine. I. Development and preparations of the vaccine: technics for assay of effects of vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 263, 153–159 (1960).

Black, F. L. & Yannet, H. Inapparent measles after γ globulin administration. JAMA 173, 1183–1188 (1960).

Good, R. A. & Zak, S. J. Disturbances in γ globulin synthesis as 'experiments of nature'. Pediatrics 18, 109–149 (1956).

Permar, S. R. et al. Role of CD8+ lymphocytes in control and clearance of measles virus infection of rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 77, 4396–4400 (2003).

Moss, W. J., Ryon, J. J., Monze, M. & Griffin, D. E. Differential regulation of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-10 during measles in Zambian children. J. Infect. Dis. 186, 879–887 (2002).

Tamashiro, V. G., Perez, H. H. & Griffin, D. E. Prospective study of the magnitude and duration of changes in tuberculin reactivity during uncomplicated and complicated measles. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 6, 451–454 (1987).

Coovadia, H. M. et al. Alterations in immune responsiveness in acute measles and chronic post-measles chest disease. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 56, 14–23 (1978).

Beckford, A. P., Kaschula, R. O. & Stephen, C. Factors associated with fatal cases of measles. A retrospective autopsy study. S. Afr. Med. J. 68, 858–863 (1985).

Greenberg, B. L. et al. Measles-associated diarrhea in hospitalized children in Lima, Peru: pathogenic agents and impact on growth. J. Infect. Dis. 163, 495–502 (1991).

Duke, T. & Mgone, C. S. Measles: not just another viral exanthem. Lancet 361, 763–773 (2003).

Hirsch, R. L. et al. Cellular immune responses during complicated and uncomplicated measles virus infections of man. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 31, 1–12 (1984).

Servet-Delprat, C. et al. Consequences of Fas-mediated human dendritic cell apoptosis induced by measles virus. J. Virol. 74, 4387–4393 (2000).

Griffin, D. E. et al. Changes in plasma IgE levels during complicated and uncomplicated measles virus infections. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 76, 206–213 (1985).

Griffin, D. E. & Ward, B. J. Differential CD4 T cell activation in measles. J. Infect. Dis. 168, 275–281 (1993).

Karp, C. L. et al. Mechanism of suppression of cell-mediated immunity by measles virus. Science 273, 228–231 (1996).

Atabani, S. F. et al. Natural measles causes prolonged suppression of interleukin-12 production. J. Infect. Dis. 184, 1–9 (2001).

Otten, M. et al. Public-health impact of accelerated measles control in the WHO African Region 2000–03. Lancet 366, 832–839 (2005). A description of the enormous progress in measles control in sub-Saharan Africa.

WHO & United Nations Children's Fund. Measles Mortality Reduction and Regional Elimination Strategic Plan 2001–2005. (WHO, Geneva, 2001).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress in reducing global measles deaths, 1999–2004. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 55, 247–249 (2006).

Sencer, D. J., Dull, H. B. & Langmuir, A. D. Epidemiologic basis for eradication of measles in 1967. Public Health Rep. 82, 253–256 (1967).

Orenstein, W. A. et al. Measles eradication: is it in our future? Am. J. Public Health 90, 1521–1525 (2000). An expert account of the prospects and challenges for global measles elimination.

de Quadros, C. A. Can measles be eradicated globally? Bull. World Health Organ. 82, 134–138 (2004). Consideration of measles eradication by the leader of the measles eradication strategies for the Pan American Health Organization.

Black, F. L. Measles endemicity in insular populations: critical community size and its evolutionary implication. J. Theor. Biol. 11, 207–211 (1966).

Bellini, W. J. & Helfand, R. F. The challenges and strategies for laboratory diagnosis of measles in an international setting. J. Infect. Dis. 187, (Suppl. 1) S283–S290 (2003).

Whittle, H. C. et al. Effect of subclinical infection on maintaining immunity against measles in vaccinated children in West Africa. Lancet 353, 98–101 (1999).

Mossong, J. et al. Modeling the impact of subclinical measles transmission in vaccinated populations with waning immunity. Am. J. Epidemiol. 150, 1238–1249 (1999).

Vardas, E. & Kreis, S. Isolation of measles virus from a naturally-immune asymptomatically re-infected individual. J. Clin. Virol. 13, 173–179 (1999).

WHO. Strategies for reducing global measles mortality. Wkly Epidem. Rec. 75, 411–416 (2000).

Kuhne, M., Brown, D. W. & Jin, L. Genetic variability of measles virus in acute and persistent infections. Infect. Genet. Evol. 6, 269–276 (2006).

WHO. Update of the nomenclature for describing the genetic characteristics of wild-type measles viruses: new genotypes and reference strains. Wkly Epidem. Rec. 78, 229–232 (2003).

Muwonge, A. et al. New measles genotype, Uganda. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1522–1526 (2005).

Rota, P. A. & Bellini, W. J. Update on the global distribution of genotypes of wild type measles viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 187, (Suppl. 1) S270–S276 (2003).

Rota, P. A., Rota, J. S., Redd, S. B., Papania, M. J. & Bellini, W. J. Genetic analysis of measles viruses isolated in the united states between 1989 and 2001: absence of an endemic genotype since 1994. J. Infect. Dis. 189, (Suppl. 1) S160–S164 (2004).

Christensen, P. E. et al. An epidemic of measles in southern Greenland, 1951. Measles in virgin soil. II. The epidemic proper. Acta. Med. Scand. 144, 430–449 (1953).

Dossetor, J., Whittle, H.C. & Greenwood, B. M. Persistent measles infection in malnourished children. BMJ 1, 1633–1635 (1977).

Permar, S. R. et al. Prolonged measles virus shedding in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children, detected by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J. Infect. Dis. 183, 532–538 (2001).

Kew, O. M. et al. Circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses: current state of knowledge. Bull. World Health Organ. 82, 16–23 (2004).

Moss, W. J., Cutts, F. & Griffin, D. E. Implications of the human immunodeficiency virus epidemic for control and eradication of measles. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29, 106–112 (1999).

Helfand, R. F., Moss, W. J., Harpaz, R., Scott, S. & Cutts, F. Evaluating the impact of the HIV pandemic on measles control and elimination. Bull. World Health Organ. 83, 329–337 (2005).

Biellik, R. et al. First 5 years of measles elimination in southern Africa: 1996–2000. Lancet 359, 1564–1568 (2002).

Ovsyannikova, I. G., Dhiman, N., Jacobson, R. M., Vierkant, R. A. & Poland, G. A. Frequency of measles virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in subjects seronegative or highly seropositive for measles vaccine. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10, 411–416 (2003).

Ovsyannikova, I. G., Jacobson, R. M. & Poland, G. A. Variation in vaccine response in normal populations. Pharmacogenomics 5, 417–427 (2004).

Cutts, F. T, Grabowsky, M. & Markowitz, L. E. The effect of dose and strain of live attenuated measles vaccines on serological responses in young infants. Biologicals 23, 95–106 (1995).

Anders, J. F., Jacobson, R. M., Poland, G. A., Jacobsen, S. J. & Wollan, P. C. Secondary failure rates of measles vaccines: a metaanalysis of published studies. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 15, 62–66 (1996).

Gans, H. A. et al. Deficiency of the humoral immune response to measles vaccine in infants immunized at age 6 months. JAMA 280, 527–532 (1998). A report on the immunological basis for the poor antibody response to the attenuated measles vaccine in young infants.

Angel, J. B. et al. Vaccine-associated measles pneumonitis in an adult with AIDS. Ann. Intern. Med. 129, 104–106 (1998).

Pan American Health Organization. Measles Eradication. Field Guide. (Pan American Health Organization, Washington DC, 1999).

Dayan, G. H. et al. Cost-effectiveness of three different vaccination strategies against measles in Zambian children. Vaccine 22, 475–484 (2004).

Uzicanin, A., Zhou, F., Eggers, R., Webb, E. & Strebel, P. Economic analysis of the 1996–1997 mass measles immunization campaigns in South Africa. Vaccine 22, 3419–3426 (2004).

Tangermann, R. H. et al. Eradication of poliomyelitis in countries affected by conflict. Bull. World Health Organ. 78, 330–338 (2000).

Connolly, M. A. et al. Communicable diseases in complex emergencies: impact and challenges. Lancet 364, 1974–1983 (2004).

Katz, S.L. Polio — new challenges in 2006. J. Clin. Virol. 36, 163–165 (2006).

Feikin, D. R. et al. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. JAMA 284, 3145–3150 (2000).

Wakefield, A. J. et al. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet 351, 637–641 (1998).

Offit, P. A. & Coffin, S. E. Communicating science to the public: MMR vaccine and autism. Vaccine 22, 1–6 (2003).

Jansen, V. A. et al. Measles outbreaks in a population with declining vaccine uptake. Science 301, 804 (2003).

DeStefano, F. & Thompson, W. W. MMR vaccine and autism: an update of the scientific evidence. Expert. Rev. Vaccines. 3, 19–22 (2004).

Madsen, K. M. et al. A population-based study of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and autism. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1477–1482 (2002).

Dilraj, A. et al. Response to different measles vaccine strains given by aerosol and subcutaneous routes to schoolchildren: a randomized trial. Lancet 355, 798–803 (2000).

Bennett, J. V. et al. Aerosolized measles and measles-rubella vaccines induce better measles antibody booster responses than injected vaccines: randomized trials in Mexican schoolchildren. Bull. World Health Organ. 80, 806–812 (2002).

Wong-Chew, R. M. et al. Induction of cellular and humoral immunity after aerosol or subcutaneous administration of Edmonston-Zagreb measles vaccine as a primary dose to 12-month-old children. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 254–257 (2004).

Polack, F. P. et al. Successful DNA immunization against measles: Neutralizing antibody against either the hemagglutinin or fusion glycoprotein protects rhesus macaques without evidence of atypical measles. Nature Med. 6, 776–781 (2000).

Premenko-Lanier, M. et al. DNA vaccination of infants in the presence of maternal antibody: a measles model in the primate. Virology 307, 67–75 (2003).

Premenko-Lanier, M., Rota, P. A., Rhodes, G. H., Bellini, W. J. & McChesney, M. B. Protection against challenge with measles virus (MV) in infant macaques by an MV DNA vaccine administered in the presence of neutralizing antibody. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 2064–2071 (2004).

Pan, C. H. et al. Inaugural article: modulation of disease, T cell responses, and measles virus clearance in monkeys vaccinated with H-encoding alphavirus replicon particles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11581–11588 (2005).

Skiadopoulos, M. H., Surman, S. R., Riggs, J. M., Collins, P. L. & Murphy, B. R. A chimeric human-bovine parainfluenza virus type 3 expressing measles virus hemagglutinin is attenuated for replication but is still immunogenic in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 75, 10498–10504 (2001).

Pasetti, M. F. et al. Attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and Shigella flexneri 2a strains mucosally deliver DNA vaccines encoding measles virus hemagglutinin, inducing specific immune responses and protection in cotton rats. J. Virol. 77, 5209–5217 (2003).

Chabot, S. et al. A novel intranasal Protollin-based measles vaccine induces mucosal and systemic neutralizing antibody responses and cell-mediated immunity in mice. Vaccine 23, 1374–1383 (2005).

Webster, D. E., Thomas, M. C., Huang, Z. & Wesselingh, S. L. The development of a plant-based vaccine for measles. Vaccine 23, 1859–1865 (2005).

Meissner, H. C, Strebel, P. M., Orenstein, W. A. Measles vaccines and the potential for worldwide eradication of measles. Pediatrics 114, 1065–1069 (2004).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles eradication: Recommendations from a meeting cosponsored by the World Health Organization, the Pan American Health Organization, and the CDC. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 46, 1–20 (1997).

Cutts, F. T., Henao-Restrepo, A. M. & Olive, J. M. Measles elimination: progress and challenges. Vaccine 17, S47–S52 (1999).

Morgan, O. W. Following in the footsteps of smallpox: can we achieve the global eradication of measles? BMC Int. Health. Hum. Rights 4, 1 (2004).

Gounder, C. The progress of the Polio Eradication Initiative: what prospects for eradicating measles? Health Policy Plan 13, 212–33 (1998).

Cutts, F. T. & Steinglass, R. Should measles be eradicated? BMJ 316, 765–767 (1998). A discussion of the broader implications of measles eradication.

Schimmer, B. & Ihekweazu, C. Polio eradication and measles immunisation in Nigeria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 63–65 (2006).

Malvoisin, E. & Wild, T. F. Measles virus glycoproteins: studies on the structure and interaction of the haemagglutinin and fusion proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 74, 2365–2372 (1993).

Schneider, U., von Messling, V., Devaux, P. & Cattaneo, R. Efficiency of measles virus entry and dissemination through different receptors. J. Virol. 76, 7460–7467 (2002).

Andres, O., Obojes, K., Kim, K. S., ter Meulen, V. & Schneider-Schaulies, J. CD46- and CD150-independent endothelial cell infection with wild-type measles viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 1189–1197 (2003).

Spehner, D., Drillien, R. & Howley, P. M. The assembly of the measles virus nucleoprotein into nucleocapsid-like particles is modulated by the phosphoprotein. Virology 232, 260–268 (1997).

Valsamakis, A. et al. Recombinant measles viruses with mutations in the C, V, or F gene have altered growth phenotypes in vivo. J. Virol. 72, 7754–7761 (1998).

Patterson, J. B., Thomas, D., Lewicki, H., Billeter, M. A. & Oldstone, M. B. V and C proteins of measles virus function as virulence factors in vivo. Virology 267, 80–89 (2000).

Schneider-Schaulies, S. & ter Meulen, V. Measles virus and immunomodulation: molecular bases and perspectives. Exp. Rev. Mol. Med. 30, 1–18 (2002).

Griffin, D. E. in Fields Virology 4th edn (eds Knipe, D.M. et al.) 1401–1441 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001).

Cutts, F. T. Measles Module 7: The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series. World Health Organization [online] (1993).

Acknowledgements

Work from the authors' laboratory was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Wellcome Trust–Burroughs Wellcome Fund Infectious Disease Initiative, the Thrasher Research Fund and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Glossary

- Agammaglobulinaemia

-

A disease state in which B lymphocytes fail to produce antibodies.

- Recall antigen

-

An antigen to which a host has previously been exposed.

- Lymphopaenia

-

A decrease in the number of circulating lymphocytes in the blood.

- Reproductive number

-

(Ro). The average number of secondary cases that occur when an infected person enters a completely susceptible population.

- Index case

-

The infected person who first introduces an infection into a population.

- Immunological immaturity

-

Developmental deficiencies in the immune responses of newborns and infants.

- Parenteral

-

The administration of a drug or vaccine other than through the intestine, usually by injection.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moss, W., Griffin, D. Global measles elimination. Nat Rev Microbiol 4, 900–908 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1550

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1550

This article is cited by

-

Information-epidemic co-evolution propagation under policy intervention in multiplex networks

Nonlinear Dynamics (2023)

-

Measles second dose vaccine utilization and associated factors among children aged 24–35 months in Sub-Saharan Africa, a multi-level analysis from recent DHS surveys

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

Immunogenicity after outbreak response immunization activities among young healthcare workers with secondary vaccine failure during the measles epidemic in Korea, 2019

BMC Infectious Diseases (2022)

-

Advances in RNA Viral Vector Technology to Reprogram Somatic Cells: The Paramyxovirus Wave

Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy (2022)

-

Estimating the nationwide transmission risk of measles in US schools and impacts of vaccination and supplemental infection control strategies

BMC Infectious Diseases (2020)