Abstract

A number of studies suggest a dysregulation of the endogenous cannabinoid system in schizophrenia (SCZ). In the present study, we examined cannabinoid CB1 receptor (CB1R) binding and mRNA expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Brodmann's area 46) of SCZ patients and controls, post-mortem. Receptor density was investigated using autoradiography with the CB1R ligand [3H] CP 55 940 and CB1R mRNA expression was measured using quantitative RT-PCR in a cohort of 16 patients with paranoid SCZ, 21 patients with non-paranoid SCZ and 37 controls matched for age, post-mortem interval and pH. All cases were obtained from the University of Sydney Tissue Resource Centre. Results were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Bonferroni tests and with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to control for demographic factors that would potentially influence CB1R expression. There was a main effect of diagnosis on [3H] CP 55 940 binding quantified across all layers of the DLPFC (F(2,71)=3.740, p=0.029). Post hoc tests indicated that this main effect was due to patients with paranoid SCZ having 22% higher levels of CB1R binding compared with the control group. When ANCOVA was employed, this effect was strengthened (F(2,67)=6.048, p=0.004) with paranoid SCZ patients differing significantly from the control (p=0.004) and from the non-paranoid group (p=0.016). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in mRNA expression between the different disease subtypes and the control group. Our findings confirm the existence of a CB1R dysregulation in SCZ and underline the need for further investigation of the role of this receptor particularly in those diagnosed with paranoid SCZ.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Cannabis and cannabis-related drugs act principally through two seven-transmembrane-domain, G protein-coupled receptors termed the cannabinoid 1 (CB1R) and cannabinoid 2 (CB2R) receptors that are also activated by endogenous ligands termed endocannabinoids. The CB1R is considered to mediate the majority of the psychoactive properties of cannabis (Ameri, 1999) and is expressed abundantly throughout the human brain (Glass et al, 1997). In the cortex, the CB1R is expressed mainly on presynaptic terminals of GABAergic inhibitory interneurons (Eggan and Lewis, 2007).

Abnormalities in the CB1R in cortical regions in schizophrenia (SCZ) have been reported in a number of studies. Dean et al (2001) found increased binding of the CB1R agonist [3H] CP 55 940, in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, Brodmann's area 9) in patients with SCZ that was independent of cannabis use before death and in caudate-putamen that appeared to be related to premorbid cannabis use in these patients. Urigüen et al (2009) reported that immunodensity of CB1R in the frontal cortex was significantly decreased in antipsychotic-treated patients with SCZ but not in drug-free patients (Urigüen et al, 2009). Looking in other cortical regions, we have previously shown an increase in the binding of the selective cannabinoid antagonist [3H] SR141716A in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients with SCZ post-mortem (Zavitsanou et al, 2004), a finding that was confirmed in the posterior cingulate cortex (Newell et al, 2006). In contrast to the receptor binding studies, reduced cortical CB1R mRNA and protein expression have been found in the post-mortem DLPFC (Brodmann's areas 9 and 46) in SCZ (Eggan et al, 2008; Eggan et al, 2010), whereas another study (Koethe et al, 2007) found no change in the density of CB1R immunopositive cells in the anterior cingulate cortex in SCZ. Importantly, a recent imaging study using the novel positron emission tomography (PET) CB1R tracer [11C] OMAR (JHU75528) showed an elevated mean binding of this tracer in patients with SCZ across all regions studied that reached significance in the pons (Wong et al, 2010a). Perhaps more importantly, the same study suggested that CB1R binding in SCZ increases with severity of the positive symptoms and decreases with severity of negative symptoms (Wong et al, 2010a). Another imaging study using the selective high affinity PET radioligand [18F] MK-9470 showed a significant increase of CB1R availability in the mesocorticolimbic circuitry, especially in the nucleus accumbens of both antipsychotic treated and untreated SCZ patients compared with controls (Ceccarini et al, 2010).

The discrepancies in the studies above may reflect methodological or regional differences, or may relate to other factors such as antipsychotic medication (eg, Urigüen et al, 2009) or cannabis consumption (Dean et al, 2001) or they may be related to cohort make up, as cohorts varied in SCZ subtype composition and the degree of symptoms varied among individuals in all of these studies. Recently, it has been suggested that different genetic and pathophysiological mechanisms may underlie different subtypes of SCZ (Chavarría-Siles et al, 2008). For example, genetic studies provide evidence that a variation of CNR1, the CB1 receptor gene, confers risk for hebephrenic (disorganized) SCZ with no association to the more general phenotype of SCZ. The same authors suggested that inclusion of other subtypes may dilute the power to find association of SCZ with changes in CNR1. Similarly, the inclusion of different disease subtypes in the post-mortem studies described above may have an impact on the measures of CB1R protein or mRNA levels and contributes to the discrepancies reported. Importantly, Giuffrida et al (2004) have shown that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide are profoundly and selectively elevated in paranoid-type SCZ, and that the levels of anandamide negatively correlate with the psychotic symptoms of the disease (Giuffrida et al, 2004).

In this study, we hypothesized that CB1R density may vary according to the disease's subtype clusters. In the past decade, SCZ research on post-mortem human tissue has matured, largely due to the widespread availability of larger cohorts that allow for examination of specific disease subtypes. Thus, to understand further the changes in CB1R in SCZ, we measured CB1R binding and mRNA expression in the DLPFC (Brodmann's area 46) of a large cohort of control subjects and subjects with SCZ to determine (a) whether these changes were disease subtype specific with focus on the paranoid subtype and (b) whether changes in CB1R binding were associated with changes in levels of mRNA expression. In our study close attention was paid to peri-mortem and demographic variables, which can impact studies of this kind (Mato and Pazos, 2004; Urigüen et al, 2009; Weickert et al, 2010).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Post-Mortem Brain Samples

All research was approved and conducted under the guidelines of the Human Research Ethics Committees at the University of Wollongong (#HE99/222) and at the University of New South Wales (#HREC07261). Tissue was provided by the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre (University of New South Wales Human Research Ethic Committee #HREC07261). Characterization and tissue preparation for this Australian SCZ cohort has been described previously (Weickert et al, 2010). A post-mortem clinical diagnosis was determined for each case through careful examination of the donor's lifetime symptom profile by experienced clinicians. The Diagnostic Instrument for Brain Studies—Revised (DIBS) was then employed. DIBS is a semi-structured instrument specifically designed for post-mortem psychiatric assessment using medical records and informants that enables diagnosis at a sub-syndrome and symptom-based level (Sundqvist et al, 2008). The DIBS was applied to the clinical summary to generate a diagnosis of SCZ based on ICD-10, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, Research Diagnostic Criteria, Schneider and Feighner criteria (Hill et al, 1996; Keks et al, 1997; Roberts et al, 1998). A diagnostic subtype was established as rated in individual items in the DIBS. For example according to the ICD-10, persons with paranoid SCZ must meet the general criteria for SCZ and must also experience prominent delusions or hallucinations. However, flattening of affect, catatonic symptoms, or incoherent speech must not dominate the clinical picture, although they may be present to a mild degree. Profiles were cross-matched with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria to determine the most appropriate subtype for the case. Normal controls had no history of significant psychological problems or psychological care, psychiatric admissions or drug detoxification, and no known history of psychiatric symptoms or substance abuse, as determined by both telephone screening and medical records, and no significant neuropathological changes upon examination of the brain (Weickert et al, 2010).

Tissue samples and sections were prepared from the large cohort of non-paranoid SCZ (n=21), paranoid SCZ (n=16), and control (n=37) cases matched for age, gender, pH, and post-mortem interval (Table 1; Weickert et al, 2010). The non-paranoid SCZ group included cases that met criteria for undifferentiated (n=7), residual (n=2), disorganized (n=5), and schizoaffective (bipolar and depressive subtype, n=7) type of SCZ (Table 1).

Tissue Dissection and Section Preparation

Tissue dissection has been described in detail previously (Weickert et al, 2010). Briefly, at autopsy, brain weight, and volume were determined (Harper et al, 1988). The fresh tissue was cut into ∼1 cm coronal slices and various anatomical areas were dissected for separate freezing. For the DLPFC dissections, frozen tissue was dissected on a dry ice platform using a dental drill (Cat# UP500-UG33, Brasseler, USA). DLPFC tissue (average weight of tissue ∼0.5 g gray matter tissue from the crown of the middle frontal gyrus) was obtained from the coronal slab corresponding to the middle one-third (rostral caudally) found anterior to the genu of the corpus callosum. The dissected tissue slices were immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C (±5 °C). Coronal tissue sections of the DLPFC (14 μm) were cut on a cryostat, thaw mounted onto microscope slides and stored at −80 °C until use.

In Vitro Autoradiography

All sections (three sections per case) were processed simultaneously to minimize experimental variance. On the day of the experiment, sections were pre-incubated for 30 min at room temperature in 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4) buffer containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Two sections per case were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature in the same buffer with the addition of 10 nM [3H] CP 55 940 (specific activity 139.6 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer, USA). Non-specific binding was determined by incubating adjacent sections (one/case) in 10 nM [3H] CP 55 940 in the presence of 10 μM CP 55 940. After the incubation all sections were washed for 1 h at 4 °C in 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1% BSA followed by a second wash for 3 h and by third wash for 5 min in the same buffer. Sections were then dipped briefly in ice-cold distilled water and then air dried.

Dried sections were apposed to Kodak Biomax MR film, together with autoradiographic standards ([3H] microscales from Amersham), in X-ray film cassettes for 30 days.

Quantitative Analysis of Autoradiographic Images

Films were analyzed by using a computer-assisted image analysis system, Multi-Analyst, connected to a GS-690 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad, USA). Two to three areas for quantification on each slide were previously defined by identifying the cyto-architectural characteristics of Brodmann's area 46 with neuronal nuclei (NeuN) immunostaining (Rajkowska and Goldman-Rakic, 1995; Yang et al, 2010). A rectangular box was drawn in each specified area from layers I-VI and density of receptor binding within these areas quantified. Quantification was performed blind to diagnosis by measuring the average optical density in three adjacent brain sections (two for the total binding and one for the non-specific binding). Non-specific binding (<20–30% in the majority of cases) was subtracted from the total binding to determine the specific binding. Optical density measurements were then converted into fmoles [3H] CP 55 940 per mg tissue equivalent (fmoles/mg TE), according to the calibration curve obtained from the tritium standards.

Total RNA Isolation and RNA Quality Assessment

Total RNA was extracted from ∼300 mg of frozen tissue per subject for qPCR analysis using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Kozlovsky et al, 2004). The quality of extracted total RNA was determined using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, California). A volume of 100–200 ng RNA was applied to an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip, without heating before loading. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) was used as an indicator of RNA quality, ranging from 1 (lowest quality) to 10 (highest quality). The cDNA was synthesized in three reactions of 3 μg of total RNA in a 26.25 μl reaction using the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

CB1R mRNA levels were measured using a pre-designed TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems) for CNR1 (Hs00275634_m1). Each 10 μl qPCR reaction contained FAM-labeled probe (250 nmol/l), primers (900 nmol/l), and 1.14 ng cDNA in 1x Taqman Universal Mastermix containing AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase, deoxynucleoside triphosphates, uracil-N-glycosylase, and passive reference. The PCR protocol used involved incubation at 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 consecutive cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Serial dilutions of pooled cDNA (from all cases) were included on every qPCR plate and used by Sequence Detection Software (SDS; Applied Biosystems) to quantify sample expression by the relative standard curve method. Control wells containing no cDNA template displayed no amplification in any assay. Efficiencies of the qPCR reactions ranged from 77 to 100%, with r2 values of between 0.95 and 1.00. All reactions were performed in triplicate. Expression levels were normalized to the geometric mean of four ‘housekeeper’ genes that did not change expression with diagnosis: ACTB (Hs99999903_m1), GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1), UBC (Hs00824723_m1), and TBP (Hs00427620_m1) (Weickert et al, 2010; Wong et al, 2010b). Population outliers were excluded if the normalized expression value was greater than two standard deviations from the group mean. As a result, RNA samples were unavailable for five members of the control cohort and 2 members of the SCZ cohort.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 14). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was employed to test for normal (Gaussian) distribution. Parametric tests were used in subsequent analysis as data were normally distributed. Mean values for binding and mRNA expression are reported ±SD.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student's t-tests were used to compare the mean brain pH, age at death, PMI, freezer storage time, brain weight, RIN, mean age of illness onset, illness duration, and estimated lifetime exposure to antipsychotics (stated as chlorpromazine equivalent dose (mg)) between the diagnostic groups (Table 1).

For continuous, descriptive variables (brain pH, age at death, PMI, freezer storage time, brain weight, RIN, age of illness onset, illness duration, and estimated lifetime exposure to antipsychotics), we tested for significant Pearson correlations for the abnormal CB1R binding and mRNA expression. Non-continuous descriptive variables such as gender (male/female), hemisphere (right/left), cause of death (suicide/other), presence of a cannabis use history (yes/no), agonal state (excellent: 1, good: 2, and poor: 3), daily alcohol intake (none: 0, low: 1, moderate: 2, high: 3, and unknown: 4), and tobacco smoking (unknown: 0, moderate: 1, and heavy: 2) were used as grouping variables with t-tests or one-way ANOVA to evaluate their effects on binding and mRNA expression.

The effects of the continuous and non-continuous variables were examined in all subjects (in both the control and SCZ group), in the control group alone, and the SCZ group (not divided into paranoid and non-paranoid SCZ) alone. Effects of the continuous and non-continuous variables were then examined in the paranoid and non-paranoid SCZ groups to ensure that our measurements were not affected by a particular variable in each subgroup.

CB1R binding and mRNA expression levels were compared between diagnostic groups (paranoid and non-paranoid SCZ and controls) using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests to account for multiple comparisons. Separate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for pH, age at death, freezer storage time, brain volume and RIN followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests were also calculated where appropriate.

Exploratory one-way ANOVAs were also performed to compare CB1R binding and mRNA expression between the diagnostic SCZ subgroups (residual, disorganized, schizoaffective, undifferentiated, paranoid) and controls. Due to low subject numbers in some groups, LSD post hoc tests were used where appropriate to reduce the risk of type II error.

Results

The mean pH, age at death, PMI, freezer storage time, brain weight, and RIN did not differ between the groups studied (paranoid and non-paranoid SCZ, and controls; 0.008⩽F⩽2.153, df=2, 0.124⩽p⩽0.992, Table 1). Also the age of onset of disease, the duration of illness, and lifetime exposure to antipsychotics (lifetime chloropromazine) did not differ between paranoid and non-paranoid groups (−0.167⩽t⩽0.167, df=35, 0.868⩽p⩽0.904, Table 1) or between the six diagnostic subgroups (F(5,31)=1.848, p=0.132). In agreement with the literature, however, SCZ cases of the disorganized subtype had the earliest mean age of onset of disease (∼20 years, Table 1).

Disease-Related Effects

One-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference between the three diagnostic groups (paranoid SCZ, non-paranoid SCZ, and control) on [3H] CP 55 940 binding in the DLPFC (F(2,71)=3.740, p=0.029, Figures 1 and 2a). Post hoc analysis (Bonferroni) indicated that patients with paranoid SCZ had significantly (22%) higher levels of binding compared with controls (58.7±13.4 vs 47.9±12.6 fmoles/mg TE, p=0.036, Figure 2a). Paranoid SCZ patients also had higher binding compared with the non-paranoid SCZ patients but this increase was not statistically significant (58.7±13.4 vs 47.9±16.2 fmoles/mg TE, p=0.068). However, given that the sample size was smaller in the patient groups compared with the control group, we may have been underpowered to detect this increase. To have sufficient power (eg, 80%) to detect an increase in binding in paranoid patients compared with the non-paranoid patients, the groups would need to be increased from n=12–17 to n=24 per group.

Typical autoradiographs showing [3H] CP55 940 binding in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in control, non-paranoid (NP SCZ), and paranoid (P SCZ) SCZ groups. Areas for quantification on each slide were previously defined by identifying the cyto-architectural characteristics of BA46 with NeuN immunostaining (Rajkowska and Goldman-Rakic, 1995; Yang et al, 2010).

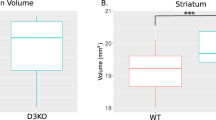

Cannabinoid CB1 receptor density (a) and mRNA (b) expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in control, non-paranoid (NP SCZ), and paranoid (P SCZ) schizophrenia patients. (a) [3H] CP 55 940 binding density in fmoles/mg TE (tissue equivalent). (b) CB1 mRNA expression normalized to the geometric mean of four housekeeping genes. #: A 22% increase in CB1 receptor density was found in the P SCZ group that was statistically significant when compared with controls in a one-way analysis of variance (F(2,71)=3.740, p=0.029) and significantly different from controls (p=0.004) following analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (F(2,67)=6.048, p=0.004). *: The 22% increase in CB1 receptor density in the P SCZ was statistically significant when compared with the NP SCZ group (p=0.016) after ANCOVA (F(2,67)=6.048, p=0.004).

Peri-mortem and demographic variables can impact CB1R density and mRNA expression in post-mortem human studies (Mato and Pazos, 2004). Therefore although most of the correlations between the continuous variables and our data were between 0.3 and 0.5 (see below and also Table 2), suggesting a moderate association (Cohen 1988), we proceeded with ANCOVA to account for continuous variables (pH, age at death, freezer storage time, and brain weight) that might impact on our data. Importantly, when ANCOVA was conducted, the significant difference between the three diagnostic groups was retained (F(2,67)=6.048, p=0.004) with paranoid SCZ patients having significantly higher binding as compared with the control group (p=0.004) and the non-paranoid SCZ group (p=0.016) (Figure 2a).

In contrast, we failed to reveal a statistically significant difference between CB1 mRNA expression in the three diagnostic groups by ANOVA (F(2,63)=2.183, p=0.121) (Figure 2b). This result remained unchanged after we controlled for continuous variables with ANCOVA (F(2,57)=2.239, p=0.116). A positive correlation was found, however, between CB1R mRNA expression and binding (r=0.384; p=0.001).

We also carried out exploratory one-way ANOVAs treating each group (residual, disorganized, schizoaffective, undifferentiated, paranoid SCZ, and controls) as a single diagnosis to determine the strength of the complex variability on CB1R binding and mRNA expression across different subtypes of SCZ. This analysis should be treated with caution, however, due to low subject numbers within some groups (Table 1). A significant effect of diagnosis on CB1R binding was found (F(5,68)=2.392, p=0.047; Figure 3a). Post hoc tests indicated that this effect was due to patients with paranoid SCZ having higher CB1R binding compared with controls (p=0.011) and to the residual SCZ group (p=0.006) and patients with residual SCZ having lower CB1R binding compared with those with undifferentiated SCZ (p=0.042; Table 1, Figure 3a). CB1R mRNA did not differ between the diagnostic subgroups (F(5,60)=1.644), p=0.162; Table 1; Figure 3b).

Cannabinoid CB1 receptor density (a) and mRNA (b) expression in the DLPFC in diagnostic subtypes of schizophrenia and controls. (a) [3H] CP 55 940 binding density in fmoles/mg TE (tissue equivalent). In an exploratory one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), where the bipolar and depressive subtypes were treated as one group (schizoaffective) and compared with controls along with the other four schizophrenia subtypes, a significant variation in CB1R density was found (F(5,68)=2.392, p=0.047). *p<0.05, $p=0.006 in LSD post hoc tests. (b) CB1 mRNA expression normalized to the geometric mean of four housekeeping genes. CB1 mRNA expression did not differ between diagnostic subtypes (F(5,60)=1.644, p=0.162) when analyzed with one-way ANOVA.

Effects of Continuous and Non-Continuous Variables

Pearson's rank order correlations for continuous variables (brain pH, age at death, PMI, freezer storage time, brain weight, RIN, age of illness onset, illness duration, and estimated lifetime exposure to antipsychotics) are presented in Table 2. The t-tests and ANOVA for non-continuous variables (gender (male/female), hemisphere (right/left), cause of death (suicide/other), presence of a cannabis use history (yes/no), agonal state (excellent: 1, good: 2, and poor: 3), daily alcohol intake (none: 0, low: 1, moderate: 2, high: 3, and unknown: 4), and tobacco smoking (unknown: 0, moderate: 1, and heavy: 2)) were performed and are presented as Supplementary information (Figures S1 and S2).

Within all subjects, [3H] CP 55 940 binding was correlated with pH (r=0.392, p=0.001), age at death (r=−0.385, p=0.002), freezer storage time (r=0.344, p=0.003), and brain weight (r=0.291, p=0.012) (Table 2). However, there was a negative correlation of borderline significance between freezer time and age at death (r=−0.208, p=0.075), which may explain the relationship between binding and freezer time. Binding levels did not correlate with PMI, or vary according to gender, hemisphere, agonal state, daily alcohol, and smoking (Table 2, Supplementary Figure S1). Significant correlations were observed between mRNA expression and pH (r=0.299, p=0.015), age at death (r=−0.356; p=0.003), and RIN (r=0.285; p=0.021) (Table 2). CB1 mRNA expression was unaffected by all other continuous (Table 2) and non-continuous variables (data not shown).

In the control group, there were significant positive correlations between CB1 binding and pH (r=0.339, p=0.040), freezer storage time (r=0.541, p=0.001) and brain weight (r=0.463, p=0.004), and a negative correlation between binding and age at death (r=−0.358, p=0.029) (Table 2). Binding was unaffected by all the other continuous and non-continuous variables (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). A significant negative correlation was also found between mRNA expression and age at death (r=−0.401, p=0.019) whereas the correlation between mRNA and freezer storage time was positive (r=0.346, p=0.045) (Table 2). The mRNA was not found to be affected by any of the non-continuous variables examined (data not shown).

In the SCZ group as a whole, binding was correlated with pH (r=0.470, p=0.003) and age at death (r=−0.374, p=0.023), and correlations of borderline significance were found between binding and PMI (r=0.285, p-0.087) and duration of illness (r=−0.322, p=0.052) (Table 2). CB1 mRNA expression was positively correlated with pH (r=0.376, p=0.034) with a correlation of borderline significance between mRNA and age at death (r=−0.303, p=0.092) (Table 2). CB1 mRNA expression was unaffected by all other continuous variables (Table 2). The non-continuous variables considered were not shown to have an effect on CB1 binding (Supplementary Figure S2) or mRNA expression (data not shown).

In the paranoid SCZ group alone, [3H] CP 55 940 binding was unaffected by all continuous and non-continuous variables except duration of illness (r=−0.527, p=0.036) (Table 2, Supplementary Figure S2). A significant positive correlation was found between mRNA expression and freezer storage time (r=0.561, p=0.037) (Table 2). CB1 mRNA expression was unaffected by all other continuous and non-continuous variables (Table 2, data not shown for non-continuous variables).

In the non-paranoid SCZ group alone, CB1 receptor density was affected by pH (r=0.526, p=0.014) but was not affected by any other continuous and non-continuous variable (Table 2, Supplementary Figure S2). CB1 mRNA expression was affected by pH (r=0.541, p=0.021) (Table 2) and was unaffected by all non-continuous variables (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Disease-Related Effects

Despite the widespread acknowledgement of the heterogeneity of SCZ, few studies have investigated whether indices of neuroreceptor densities/mRNA expression are associated with different clinical subtypes of the disorder. In the present study, we report a significant increase of 22% in cannabinoid CB1R binding in the DLPFC in a subgroup of patients who suffered from paranoid SCZ compared with normal controls. The patients with paranoid SCZ also had elevated CB1R binding compared with patients with non-paranoid SCZ.

Looking at a smaller cohort of 14 SCZ patients and matched controls, Dean et al (2001) found increased [3H] CP 55 940 binding in Brodmann's area 9 of the DLPFC. We have also previously shown an increase in binding sites for the selective antagonist [3H] SR141716A in the anterior cingulate cortex of 10 SCZ patients compared with their matched controls (Zavitsanou et al, 2004), a finding that was confirmed in the posterior cingulate cortex with [3H] CP 55 940 (Newell et al, 2006). In contrast, Deng et al (2007) found no changes in both the binding of [3H] SR141716A or [3H] CP 55 940 in the superior temporal gyrus in eight SCZ patients. Recently, the development of suitable radioligands that target the CB1R in vivo in the living brain has allowed for the study of CB1Rs in SCZ patients using PET. In agreement with the post-mortem studies, two recent PET studies (Wong et al, 2010a; Ceccarini et al, 2010) also reported elevated CB1R binding in the pons and nucleus accumbens respectively in patients with SCZ.

The increase in CB1R binding we observed in the present study was not accompanied by changes in CB1R mRNA. Despite this lack of overall change in primary transcript levels of CB1R mRNA, there was a positive correlation between mRNA and binding in SCZ. As this correlation was of a moderate effect, it is possible that the increase in CB1R binding sites without a similar change in mRNA may arise from a change in post-translational processes such as a greater rate of translation per mRNA molecule or less receptor degradation/turnover. In agreement with our mRNA data and using the same methodology, Urigüen et al (2009) reported unchanged CB1 mRNA expression in Brodmann's area 9 in SCZ. In contrast, Eggan et al (2008) reported decreases in both CB1R immunoreactivity and mRNA expression in the DLPFC (Brodmann's area 9) and in CB1R immunoreactivity in Brodmann's area 24 in the DLPFC in SCZ employing immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization.

The discrepancy between ligand binding and immunocytochemistry approaches to CB1R protein measurement needs to be understood and suggests that changes in the CB1R system in SCZ are not simple or straightforward. Clearly, more studies will be needed to reach a consensus. [3H] CP 55 940 has equal affinity for both CB1R and CB2R, however, binding of [3H] CP 55 940 to CB2R is unlikely to have influenced our results as this receptor is expressed at much lower levels in the mammalian brain than the CB1R (Onaivi et al, 2006; Liu et al, 2009) and the cortex is among the regions that express the lowest levels of CB2R in the human brain (Liu et al, 2009). Receptor binding studies are more likely to quantitatively reflect actual numbers of CB1R binding sites in brain and the consistent effect of a broad range of ligands in both post-mortem and in vivo studies points to an increase in CB1R in SCZ. In addition, CB1R antibodies may not qualitatively or quantitatively stain receptors in all cell types or subcellular compartments (Eggan and Lewis, 2007) and may therefore fail to detect receptors that are detectable using radioligand binding.

In addition to methodological differences, the differences between the studies mentioned above may relate to differences in cohort make-up. Indeed, the wide range of SCZ subtypes that are included in post-mortem studies together with the lack of adequate numbers of cases in each subgroup may dilute the power to find neurochemical changes restricted to a specific diagnostic subtype. Indeed, we observed differences of only borderline significance when binding in the entire SCZ cohort was compared with controls as a whole. Interestingly, in our cohort the average binding in the schizoaffective cases (depressive and bipolar subtypes pooled) was similar to the controls, whereas the disorganized and residual groups had lower binding compared with controls (Table 1). Furthermore, in an exploratory investigation, which should be treated with caution due to low subject numbers in some diagnostic subgroups, significant differences were found between binding in the residual group with that in the undifferentiated and paranoid groups. These results need to be confirmed in cohorts consisting of larger numbers. If confirmed, however, this evidence raises the possibility that CB1Rs may show very specific adaptations in the cortical regions of different subtypes of SCZ. Overall, most studies support an increase in cortical CB1R binding in patients with SCZ, and our study suggests that this increase may be especially evident in people suffering from paranoid SCZ.

Although in the present study the mean onset of the disease did not differ between the paranoid and non-paranoid group, several lines of evidence support that the paranoid subtype of SCZ is associated with later disease onset and better prognosis (McGlashan and Fenton, 1991; Zalewski et al, 1998). A connection between an abnormality in the endocannabinoid system and paranoid SCZ has been reported. In 1976, the paranoid psychosis associated with long term cannabis use was compared with the symptoms of paranoid SCZ in 25 psychiatric patients (Thacore and Shukla, 1976). Subjects with acute cannabis intoxication often display a SCZ-like syndrome with hallucinations, altered judgement, false beliefs, and cognitive impairment that are also features of paranoid SCZ (De Marchi et al, 2003; D’Souza et al, 2009). CSF levels of the endocannabinoid, anandamide, are profoundly and selectively elevated in paranoid-type SCZ as compared with dementia or affective disorder patients, negatively correlate with the psychotic symptoms of the disease and are normalized by treatment with typical but not atypical antipsychotic drugs (Giuffrida et al, 2004). Interestingly in two recent PET imaging studies, CB1R binding (expressed as the distribution volume) in the frontal lobe and the middle and posterior cingulate cortex correlated with positive and inversely correlated with the negative symptoms (Wong et al, 2010a) whereas CB1R uptake in the insula was positively associated with the positive PANSS subscale ‘conceptual disorganization’ and negatively correlated to psychomotor speed and attention in the amygdala, hippocampus, and putamen (Ceccarini et al, 2010). These results taken together with the present study suggest that it may be possible to relate CB1R abnormalities to the severity of clinical symptoms in SCZ (Wong et al, 2010a) or to specific subtypes (present study) and also that subjects with SCZ with abnormal CB1Rs may have an inherent tendency to a particular symptomatology (ie, paranoia).

As CB1Rs in the human and monkey DLPFC are thought to be localized in inhibitory GABAergic interneurons of the CCK-expressing subtype (Glass et al, 1997; Eggan and Lewis, 2007), it is likely that the majority of CB1R binding observed in the present study in the paranoid group comes from intrinsic sources. It is also possible that this increase reflects a compensatory response that, if assumed to result in reduced inhibitory input from GABAergic interneurons (Bodor et al, 2005), could be related to tighter control of cognitive function in these patients and also to increased paranoid ideation. Post-mortem examination of other relevant brain regions such as the hippocampus and striatum, which contain high density of CB1Rs would illuminate this issue.

Implications for Pharmacotherapy

In general, agents that bind to CB1R and can act as antagonists display antipsychotic properties in animal models (Zuardi et al, 2006; Roser et al, 2010). The non-psychotomimetic cannabis constituent cannabidiol, which antagonizes the effects of THC (Pertwee 2008), as well as the synthetic CB1R antagonist rimonabant (SR141716A) have been evaluated in humans as antipsychotics for the treatment of SCZ (Roser et al, 2010). Some conflicting results, however, have been obtained in these studies (Roser et al, 2010; Leweke et al, 2009). In a double-blind clinical trial involving 42 patients with paranoid SCZ, Leweke et al (2009) reported that cannabidiol possessed substantial antipsychotic properties with fewer side effects than amisulpride. Following cannabidiol administration, Zuardi et al, (1995) also reported an improvement in symptoms in one female with SCZ , however, no improvement was seen in three treatment-resistant males (Zuardi et al, 2006). Rimonabant improved psychiatric symptoms in some patients with SCZ (Kelly et al, 2011) but was shown to have no effect on psychopathology in comparison to placebo by Meltzer et al (2004) and was associated with a relapse to psychosis in another study (Ugur et al, 2008). The results of the current study may help to explain the conflicting findings on the effects of cannabinoid antagonists in humans; that is cannabinoid antagonists may be more effective for treating paranoid SCZ than other subtypes of the disease owing in part to the higher levels of CB1 receptor we observed in this group.

Effects of Continuous and Non-Continuous Variables

Many demographic and peri-mortem factors influence CB1R mRNA expression and/or binding in addition to any effects of SCZ (Mato and Pazos, 2004; Eggan et al, 2008; Ludányi et al, 2008; Urigüen et al, 2009). For example, CB1R densities are influenced by aging, post-mortem delay and freezer storage time (our study and Mato and Pazos, 2004). We found negative correlations between CB1R binding and mRNA with age suggesting that CB1R density in the DLPFC decreases with age. Similar findings have been reported in the literature in the frontal cortex of normal individuals (Mato and Pazos, 2004). In agreement with Mato and Pazos (2004), we found no significant correlation for CB1R with post-mortem delay but a positive correlation with freezer storage time that is in contrast to the findings of Mato and Pazos (2004) who reported that CB1R density is reduced with freezer storage time. However, in our cohort, there was a negative correlation of borderline significance between freezer time and age that might explain the relationship between binding and freezer time. Brain weight was also found to positively correlate with CB1R binding and whereas there is no convincing explanation in relation to this finding, it is of interest that Harrison et al (2010) reported a positive correlation between human brain weight and the expression of two ‘housekeeping genes’ and suggested that brain weight should be added to the list of variables to be taken into account in post-mortem studies. Our study shows the retention of a statistically significant elevation in the [3H] CP 55 940 binding in paranoid SCZ after all these variables were co-varied for. Along with careful matching of disease and control group, we used correlation and covariate analysis to identify and control for confounding variables, with stringent post hoc tests (Bonferroni tests) to account for multiple comparisons. Therefore, the significant difference associated with the diagnostic subtype that we observed here is robust.

Antipsychotic medication may also have had an effect on CB1R binding and mRNA expression in our disease groups (Sundram et al, 2005; Cheng et al, 2008; Urigüen et al, 2009; Secher et al, 2010). Unfortunately, absence of adequate brain tissue from drug naïve persons with SCZ makes it difficult to overcome this problem. However, a number of points should be considered. First, we found no correlation between lifetime antipsychotic drug exposure and CB1R density or mRNA expression. Second, the existing body of evidence suggests overall that most antipsychotic drugs do not bind the CB1R in vitro (Theisen et al, 2007). In rats, antipsychotics do not change the CB1R binding in the cortex and striatum (the regions with some of the highest density of CB1R) (Sundram et al, 2005; Wiley et al, 2008) but may decrease the CB1R in the brainstem and nucleus accumbens (Sundram et al, 2005; Weston-Green et al, 2008), or, in the case of risperidone, may increase CB1R binding in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala (Secher et al, 2010). Aripiprazole treatment is associated with upregulation in CB1R mRNA in the rat frontal cortex (Cheng et al, 2008), however, Urigüen et al (2009) reported no effect of antipsychotic treatment on levels of CB1R mRNA in human subjects with SCZ compared with controls. It should be noted that in the SCZ group as a whole, 31 of the 37 cases were treated mainly with typical antipsychotics and the remaining six cases received predominately atypical antipsychotic drugs. Within the paranoid group alone, 14 out of 16 cases were treated mainly with typical antipsychotics. Third, Ceccarini et al (2010) using the selective high affinity PET radioligand [18F] MK-9470 showed a significant increase of CB1R availability in the mesocorticolimbic circuitry, especially in the nucleus accumbens of both antipsychotic treated and untreated (n=5 drug naïve and n=4 after drug washout) SCZ patients compared with controls, supporting the notion that CB1Rs can be increased regardless of antipsychotic.

Finally, another potential influence on CB1R binding and mRNA expression may be the effects of cannabis consumption in our SCZ group as chronic cannabinoid exposure has been shown to downregulate CB1R binding in animal models (Dalton et al, 2009) and humans (Villares, 2007). In the current study, however, we observed no effect of cannabis exposure on CB1R density or mRNA in the DLPFC, in agreement with other studies in the DLPFC (Dean et al, 2001; Eggan et al, 2010) and superior temporal gyrus (Deng et al, 2007).

CONCLUSIONS

Our finding of increased CB1R binding in paranoid SCZ could reflect a greater involvement of the endocannabinoid system in the DLPFC in this subtype of patients with SCZ as may be suggested by their more marked positive thought disorders and delusional symptoms. An understanding between neurochemical deficits in the endocannabinoid system and SCZ subtypes may ultimately emerge from investigations that combine genetics with brain imaging approaches, biological assays, and neuropsychological techniques in specific SCZ subtypes. The present findings particularly if confirmed by further investigations, would suggest different levels of participation of elements of the endocannabinoid system in the different subtypes of SCZ, arguing for distinct neurochemical correlates of clinical subtypes and raising the possibility of instituting psychopharmacological treatment accordingly.

References

Ameri A (1999). The effects of cannabinoids on the brain. Prog Neurobiol 58: 315–348.

Bodor AL, Katona I, Nyiri G, Mackie K, Ledent C, Hajos N et al (2005). Endocannabinoid signaling in rat somatosensory cortex: laminar differences and involvement of specific interneuron types. J Neurosci 25: 6845–6856.

Ceccarini J, De Hert M, van Winkel R, Koethe D, Bormans G, Leweke M et al (2010). In vivo PET imaging of cerebral type 1 cannabinoid receptor availability in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res 117: 170.

Chavarría-Siles I, Contreras-Rojas J, Hare E, Walss-Bass C, Quezada P, Dassori A et al (2008). Cannabinoid receptor 1 gene (CNR1) and susceptibility to a quantitative phenotype for hebephrenic schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 147: 279–284.

Cheng MC, Liao DL, Hsiung CA, Chen CY, Liao YC, Chen CH (2008). Chronic treatment with aripiprazole induces differential gene expression in the rat frontal cortex. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 11: 207–216.

Cohen J (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, New Jersey.

Dalton VS, Wang H, Zavitsanou K (2009). HU210-induced downregulation in cannabinoid CB1 receptor binding strongly correlates with body weight loss in the adult rat. Neurochem Res 34: 1343–1353.

De Marchi N, De Petrocellis L, Orlando P, Daniele F, Fezza F, Di Marzo V (2003). Endocannabinoid signalling in the blood of patients with schizophrenia. Lipids Health Dis 2: 5.

Dean B, Sundram S, Bradbury R, Scarr E, Copolov D (2001). Studies on [3H]CP-55940 binding in the human central nervous system: regional specific changes in density of cannabinoid-1 receptors associated with schizophrenia and cannabis use. Neuroscience 103: 9–15.

Deng C, Han M, Huang X-F (2007). No changes in densities of cannabinoid receptors in the superior temporal gyrus in schizophrenia. Neurosci Bull 23: 341–347.

D’Souza DC, Sewell RA, Ranganathan M (2009). Cannabis and psychosis/schizophrenia: human studies. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 259: 413–431.

Eggan SM, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA (2008). Reduced cortical cannabinoid 1 receptor messenger RNA and protein expression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65: 772–784.

Eggan SM, Lewis DA (2007). Immunocytochemical distribution of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor in the primate neocortex: a regional and laminar analysis. Cereb Cortex 17: 175–191.

Eggan SM, Stoyak SR, Verrico CD, Lewis DA (2010). Cannabinoid CB1 receptor immunoreactivity in the prefrontal cortex: Comparison of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 2060–2071.

Giuffrida A, Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Schreiber D, Koethe D, Faulhaber J et al (2004). Cerebrospinal anandamide levels are elevated in acute schizophrenia and are inversely correlated with psychotic symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 2108–2114.

Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RL (1997). Cannabinoid receptors in the human brain: a detailed anatomical and quantitative autoradiographic study in the fetal, neonatal and adult human brain. Neuroscience 77: 299–318.

Harper CG, Kril JJ, Daly JM (1988). Brain shrinkage in alcoholics is not caused by changes in hydration: a pathological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 51: 124–127.

Harrison PJ, Laatikainen LM, Tunbridge EM, Eastwood SL (2010). Human brain weight is correlated with expression of the ‘housekeeping genes’ beta-2-microglobulin (beta2M) and TATA-binding protein (TBP). Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 36: 498–504.

Hill C, Keks NA, Roberts S, Opeskin K, Dean B, MacKinnon A et al (1996). Problem of diagnosis in postmortem brain studies of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 153: 533–537.

Keks NA, Hill C, Roberts S, Dean B, Opeskin K, MacKinnon A et al (1997). Diagnostic instrument for brain studies (DIBS). Schizophrenia Res 24: 34.

Kelly DL, Gorelick DA, Conley RR, Boggs DL, Linthicum J, Liu F et al (2011). Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor antagonist rimonabant on psychiatric symptoms in overweight people with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 31: 86–91.

Koethe D, Llenos IC, Dulay JR, Hoyer C, Torrey EF, Leweke FM et al (2007). Expression of CB1 cannabinoid receptor in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. J Neural Transm 114: 1055–1063.

Kozlovsky N, Weickert CS, Tomaskovic-Crook E, Kleinman JE, Belmaker RH, Agam G (2004). Reduced GSK-3beta mRNA levels in postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic patients. J Neural Transm 111: 1583–1592.

Leweke FM, Koethe D, Pahlisch F, Schreiber D, Gerth CW, Nolden BM et al (2009). Antipsychotic effects of cannabidiol. Eur Psychiatry 24 (Suppl 1): 207.

Liu Q-R, Pan C-H, Hishimoto A, Li C-Y, Xi Z-X, Llorente-Berzal A et al (2009). Species differences in cannabinoid receptor 2 (CNR2 gene): identification of novel human and rodent CB2 isoforms, differential tissue expression and regulation by cannabinoid receptor ligands. Genes Brain Behav 8: 519–530.

Ludányi A, Eross L, Czirják S, Vajda J, Halász P, Watanabe M et al (2008). Downregulation of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor and related molecular elements of the endocannabinoid system in epileptic human hippocampus. J Neurosci 28: 2976–2990.

Mato S, Pazos A (2004). Influence of age, postmortem delay and freezing storage period on cannabinoid receptor density and functionality in human brain. Neuropharmacology 46: 716–726.

McGlashan TH, Fenton WS (1991). Classical subtypes for schizophrenia: literature review for DSM-IV. Schizophr Bull 17: 609–632.

Meltzer HY, Arvanitis L, Bauer D, Rein W (2004). Placebo-controlled evaluation of four novel compounds for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 161: 975–984.

Newell KA, Deng C, Huang X-F (2006). Increased cannabinoid receptor density in the posterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Exp Brain Res 172: 556–560.

Pertwee RG (2008). The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: (delta)9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and (delta)9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br J Pharmacol 153: 199–215.

Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong J-P, Patel S, Perchuk A, Meozzi PA et al (2006). Discovery of the presence and functional expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1074: 514–536.

Rajkowska G, Goldman-Rakic PS (1995). Cytoarchitectonic definition of prefrontal areas in the normal human cortex: I. Remapping of areas 9 and 46 using quantitative criteria. Cereb Cortex 5: 307–322.

Roberts S, Hill C, Dean B, Keks NA, Opeskin K Copolov D (1998). Confirmation of the diagnosis of schizophrenia after death using DSM-IV: a Victorian experience. Aust NZ J Psych 32: 73–76.

Roser P, Vollenweider FX, Kawohl W (2010). Potential antipsychotic properties of central cannabinoid (CB1) receptor antagonists. World J Biol Psychiatry 11 (2 Part 2): 208–219.

Secher A, Husum H, Holst B, Egerod KL, Mellerup E (2010). Risperidone treatment increases CB1 receptor binding in rat brain. Neuroendocrinology 91: 155–168.

Sundram S, Copolov D, Dean B (2005). Clozapine decreases [3H] CP 55940 binding to the cannabinoid 1 receptor in the rat nucleus accumbens. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 371: 428–433.

Sundqvist N, Garrick T, Bishop I, Harper C (2008). Reliability of post-mortem psychiatric diagnosis for neuroscience research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 42: 221–227.

Thacore VR, Shukla SR (1976). Cannabis psychosis and paranoid schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 33: 383–386.

Theisen FM, Haberhausen M, Firnges MA, Gregory P, Reinders JH, Remschmidt H et al (2007). No evidence for binding of clozapine, olanzapine and/or haloperidol to selected receptors involved in body weight regulation. Pharmacogenomics J 7: 275–281.

Ugur T, Bartels M, Kis B, Scherbaum N (2008). Psychosis following anti-obesity treatment with rimonabant. Obes Facts 1: 103–105.

Urigüen L, García-Fuster MJ, Callado LF, Morentin B, La Harpe R, Casadó V et al (2009). Immunodensity and mRNA expression of A2A adenosine, D2 dopamine, and CB1 cannabinoid receptors in postmortem frontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia: effect of antipsychotic treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206: 313–324.

Villares J (2007). Chronic use of marijuana decreases cannabinoid receptor binding and mRNA expression in the human brain. Neuroscience 145: 323–334.

Weickert CS, Sheedy D, Rothmond DA, Dedova I, Fung S, Garrick T et al (2010). Selection of reference gene expression in a schizophrenia brain cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 44: 59–70.

Weston-Green K, Huang XF, Han M, Deng C (2008). The effects of antipsychotics on the density of cannabinoid receptors in the dorsal vagal complex of rats: implications for olanzapine-induced weight gain. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 11: 827–835.

Wiley JL, Kendler SH, Burston JJ, Howard DR, Selley DE, Sim-Selley LJ (2008). Antipsychotic-induced alterations in CB1 receptor-mediated G-protein signaling and in vivo pharmacology in rats. Neuropharmacology 55: 1183–1190.

Wong DF, Kuwabara H, Horti AG, Raymont V, Brasic J, Guevara M et al (2010a). Quantification of cerebral cannabinoid receptors subtype 1 (CB1) in healthy subjects and schizophrenia by the novel PET radioligand [11C]OMAR. Neuroimage 52: 1505–1513.

Wong J, Hyde TM, Cassano HL, Deep-Soboslay A, Kleinman JE, Weickert CS (2010b). Promoter specific alterations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in schizophrenia. Neuroscience 169: 1071–1084.

Yang Y, Fung SJ, Rothwell A, Tianmei S, Weickert CS (2010). Increased interstitial white matter neuron density in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of people with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 69: 63–70.

Zalewski C, Johnson-Selfridge MT, Ohriner S, Zarrella K, Seltzer JC (1998). A review of neuropsychological differences between paranoid and nonparanoid schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull 24: 127–145.

Zavitsanou K, Garrick T, Huang X-F (2004). Selective antagonist [3H]SR141716A binding to cannabinoid CB1 receptors is increased in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 28: 355–360.

Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Hallak JE, Moreira FA, Guimaraes FS (2006). Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, as an antipsychotic drug. Braz J Med Biol Res 39: 421–429.

Zuardi AW, Morais SL, Guimaraes FS, Mechoulam R (1995). Antipsychotic effect of cannabidiol. J Clin Psychiatry 56: 485–486.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Schizophrenia Research Institute, utilizing infrastructure funding from New South Wales Health, the Macquarie Group Foundation, Neuroscience Research Australia, and the University of New South Wales. Tissues were received from the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre at the University of Sydney, which is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Schizophrenia Research Institute, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIH (NIAAA) R24AA012725). We thank Nina Sundqvist of the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre for her assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dalton, V., Long, L., Weickert, C. et al. Paranoid Schizophrenia is Characterized by Increased CB1 Receptor Binding in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 1620–1630 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.43

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.43

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cannabinoids, reward processing, and psychosis

Psychopharmacology (2022)

-

Targeting the endocannabinoid system: a predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine-directed approach to the management of brain pathologies

EPMA Journal (2020)

-

Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Pathophysiology of Schizophrenia: Implications for Pharmacological Intervention

CNS Drugs (2018)

-

Cannabinoids and glial cells: possible mechanism to understand schizophrenia

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2018)

-

Rekreationaler Cannabiskonsum in Jugend und Adoleszenz

Pädiatrie & Pädologie (2017)