Abstract

Background:

At least 30% of patients with primary resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) will experience a relapse in their disease within 5 years following definitive treatment. Clinicopathological predictors have proved to be suboptimal in identifying high-risk patients. We aimed to establish whether inflammation-based scores offer an improved prognostic ability in terms of estimating overall (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) in a cohort of operable, early-stage NSCLC patients.

Methods:

Clinicopathological, demographic and treatment data were collected prospectively for 220 patients operated for primary NSCLC at the Hammersmith Hospital from 2004 to 2011. Pretreatment modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were tested together with established prognostic factors in uni- and multivariate Cox regression analyses of OS and RFS.

Results:

Half of the patients were male, with a median age of 65. A total of 57% were classified as stage I with adenocarcinoma being the most prevalent subtype (60%). Univariate analyses of survival revealed stage (P<0.001), grade (P=0.02), lymphovascular (LVI, P=0.001), visceral pleural invasion (VPI, P=0.003), mGPS (P=0.02) and NLR (P=0.04) as predictors of OS, with stage (P<0.001), VPI (P=0.02) and NLR (P=0.002) being confirmed as independent prognostic factors on multivariate analyses. Patients with more advanced stage (P<0.001) and LVI (P=0.008) had significantly shorter RFS.

Conclusions:

An elevated NLR identifies operable NSCLC patients with a poor prognostic outlook and an OS difference of almost 2 years compared to those with a normal score at diagnosis. Our study validates the clinical utility of the NLR in early-stage NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80% of primary bronchogenic carcinomas (Govindan et al, 2006) and leads the ranking of cancer-related mortality in the western world (Siegel et al, 2012). The prognosis of NSCLC is however stage dependent and only patients who present with early-stage disease, adequate pulmonary reserve and preserved performance status are candidates for resection, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 70% to 80% (Sakurai et al, 2010) in stage IA to only 30% in stage IIIA (Goya et al, 2005) disease. Recently, increasing research efforts have been directed towards the identification of clinical, pathological and biologic factors that can identify the 30% of patients with early-stage disease who will experience tumour recurrence despite adequate radical treatment. As recurrence is a major determinant of patient mortality, the prospect of predicting disease relapse at presentation might result in an improved treatment allocation such that patients at high risk of recurrence may be offered adjuvant therapies following radical surgery. In this context, previous studies have identified clinicopathological features such as larger tumour size, the presence of lymphovascular (LVI) (Lopez Guerra et al, 2013) or visceral pleural invasion (VPI) (Fibla et al, 2012) as adverse prognostic traits in early-stage NSCLC. However, conflicting results emerging from independent studies have cast doubts upon the reliability of these prognostic factors (Hung et al, 2007). More recent studies have focussed on the differential protein expression profile discriminating recurrent from non-recurrent NSCLC. For example, a distinct upregulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (m-TOR) has emerged as a peculiar trait associated with disease recurrence in independent cohorts (Dhillon et al, 2010; Gately et al, 2012).

Systemic inflammation represents an area of growing interest in the management and prognostic assessment of solid tumours. It has been shown that most of the systemic symptoms relating to the presence of cancer including weight loss, anorexia, cachexia and anaemia are inflammatory driven and result from a condition of systemic cytokine excess that can be either triggered by the tumour itself or as part of the host’s innate response against cancer (Moore et al, 2010).

A subclinical inflammatory diathesis associated with hypoalbuminaemia, raised C-reactive protein (CRP) and derangements in the full blood count such as lymphopenia combined with reactive neutrophilia and thrombocytosis, are known independent prognostic factors for a wide variety of solid tumours (McMillan, 2012). Prognostic indices based on such laboratory parameters, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS), which combines hypoalbuminaemia and elevated CRP in a 3-tiered prognostic model, have emerged as objective, inexpensive and stage-independent predictors of survival in cancer (Proctor et al, 2011).

There is mounting evidence supporting a prognostic role for the NLR (Yao et al, 2012), PLR (Arrieta et al, 2010) and mGPS (Forrest et al, 2005) in NSCLC. However, most of the studies have focussed on inoperable NSCLC a patient subgroup where cancer cachexia and poor performance status are far more prevalent than in early-stage disease (Forrest et al, 2004, 2005; Giannousi et al, 2012). Moreover, studies investigating the prognostic impact of systemic inflammation in early NSCLC were conducted in Asian populations (Tomita et al, 2011, 2012), where inherent differences exist in terms of molecular features (Sequist et al, 2007) and survival outcomes compared with western populations (Ou et al, 2009). Following on from our previous experience in hepatocellular carcinoma, where we validated a new inflammation-based index as a stage-independent predictor of survival (Pinato et al, 2012c); here, we have evaluated and compared the prognostic value of a panel inflammatory biomarkers such as NLR, PLR and mGPS in a western population with resectable NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Patient population

A series of 220 consecutive patients who underwent surgical treatment for primary NSCLC at Imperial College NHS Trust from 2004 to 2011 were included in a prospectively maintained database. Patients with evidence of an ongoing systemic inflammatory reaction (i.e., active infection or the presence of chronic inflammatory conditions) were excluded. Histological subclassification, grade, pathological stage according to the TNM Classification (7th edition) (Sobin et al, 2009) and the presence of adverse features such as lymphovascular, pleural invasion or evidence of residual tumour at the resection margin were confirmed following archival haematoxylin and eosin slides review by a consultant histopathologist with expertise in lung pathology (FM). Complete clinical and follow-up information including patient’s demographics, performance status and complete preoperative blood picture were recorded. Tumour recurrence during routine post-surgical follow-up was recorded. Overall (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) times were calculated from the time of surgery. Inflammation-based prognostic scores were calculated on preoperative blood tests as previously described (Pinato et al, 2012c). Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and NLR were derived by respectively dividing either platelet or neutrophil absolute counts with the total lymphocyte count. A resulting ratio of >300 was used to define an elevated PLR whereas a cutoff point of >5 was used to define an elevated NLR in keeping with the previously published literature (Pinato et al, 2012a). The mGPS was computed based on serum albumin and CRP levels. Briefly, patients with both normal albumin (>35 g l−1) and CRP (<10 mg l−1) concentrations were scored as 0. Patients in whom only one of these abnormalities was present were allocated a score of 1, while those with both abnormal CRP and albumin were given a score of 2. The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

The presence of significant associations between clinico-pathological variables was determined by means of Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Kaplan–Meier statistics and log-rank test were used to study the impact of the different clinical factors associated with OS and RFS on univariate analysis, with significant variables (P<0.05) being further tested on a multivariate stepwise backward Cox regression model to validate their independent prognostic value. Variables with a P-value of greater than 0.10 were removed from the model. A P-value of <0.05 was taken to be significant. All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS statistical package 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinicopathologic profile of patients

The baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 220 subjects were identified, 50% males with a median age of 65 years. All patients had a Karnofsky performance status of ⩾90 and adequate pulmonary reserve with FEV1 values >1.5 l assessed before surgery. Primary lung adenocarcinoma was the most prevalent histotype (60%) followed by squamous cell carcinoma (24%). Pathological examination revealed 57% of the patients being classified as stage I. Lymphatic diffusion to N1 nodes was present in 17% of the patients, while 6% had positive N2 nodes. N3 diffusion was found in 1% of the patients. According to clinical criteria, a total of 15 patients received adjuvant radiotherapy following radical surgery, while systemic chemotherapy was administered in 16 subjects. Combined adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy was initiated in eight subjects. The most commonly prescribed chemotherapy regimen was three-weekly carboplatin AUC 5 and gemcitabine 1000 mg m−2 days 1 and 8 of each 21-day cycle for 4 cycles (50%), followed by cisplatin-based regimens either in combination with gemcitabine (25%) or pemetrexed (25%).

On the basis of the preoperative complete blood picture, 65 patients (32%) were hypoalbuminaemic (median 37 g l−1, range 19–50 g l−1) while 66 (31%) had a CRP of >10 mg l−1 (median 5, range 0–229 mg l−1). The mGPS could be reconstructed in 200 patients due to missing preoperative CRP (n=8) or albumin values (n=12). An abnormal mGPS (score 1–2) was found in 68 patients (31%). An NLR of >5 was found in 21 patients (10%), while only 8 patients (3%) had a PLR of >300. Patients with advanced mGPS were more likely to be have Hb values <12 (P<0.001), less differentiated tumours (P=0.006) with a higher proportion of pleural invasion (P=0.03). Patients with an elevated NLR were more likely to be anaemic (P=0.02). Among patients with an NLR of >5 at diagnosis, a total of two patients received adjuvant treatments consisting of four cycles of cisplatin/etoposide chemotherapy in one case and post-operative radiation therapy in the second.

Inflammation-based indices and survival

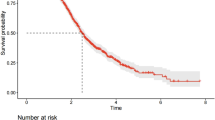

At the end of observation (September 2012), 51 patients (23%) had documented evidence of disease relapse and 61 had died (28%). The median OS of the entire cohort was 13 months (range 1–87 months) while the median RFS was 11 months (range 1–87 months). In total, 114 patients (52%) had a documented follow-up period extending beyond 12 months from diagnosis.

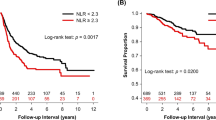

Univariate analyses revealed pTNM stage (<0.001), tumour grade (P=0.01), the presence of lymphovascular (P=0.001), pleural invasion (P=0.003), NLR>5 (P=0.04, Figure 1A) and advanced mGPS (P=0.02, Figure 1B) as significant predictors of OS. Multivariate analysis confirmed pTNM stage (P<0.001), the presence of pleural invasion (P=0.02) and NLR>5 (P=0.002) as independent risk factors predicting patients’ mortality (Table 2). Patients in whom the NLR was >5 had a median OS of 22 months (95% confidence interval (CI) 15–29 months) while patients with NLR<5 had a median OS value of 45 months (95% CI 36–54 months). When stratified according to the mGPS, median OS was 50 months for mGPS 0 (95% CI 37–62 months), 23 months for mGPS 1 (95% CI 10–36 months) and 44 months for mGPS 2 (95%CI 6.8–81). Neither mGPS (P=0.21), NLR (P=0.63) nor PLR (P=0.54) predicted shorter RFS after surgery. Significant predictors of tumour relapse included pTNM stage (P<0.001) and the presence of LVI (P=0.008).

Discussion

The connection between inflammation and cancer dates back to the origin of cellular pathology itself, when Rudolf Virchow first hypothesised a pathogenic role for the immune infiltrate commonly found adjacent to most neoplastic tissues (Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001). After almost two centuries, mechanistic studies have provided solid evidence to support the pathogenic and prognostic importance of a pro-inflammatory tumour microenvironment, which is currently considered as a hallmark of cancer progression (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011).

Chronic inflammation predates the clinical onset of NSCLC (O'Callaghan et al, 2010) and the biochemical ‘cross-talk’ between inflammatory cells and the growing neoplastic clone can influence tumour cell survival acting on immune-evasion systems and by enhancing angiogenesis (Bremnes et al, 2011). The systemic effects of cancer-related inflammation can be easily quantified using routinely available blood parameters such as NLR, PLR and mGPS, all of which have been explored as prognostic traits in NSCLC (Forrest et al, 2005; Arrieta et al, 2010; Tomita et al, 2012).

In our study, we assessed all three parameters to evaluate whether the presence of a subclinical systemic inflammatory reaction before definitive treatment could better identify patients who would have inferior survival outcomes after surgery. Strikingly, we found that the NLR was the only inflammation-based score with independent prognostic prediction on OS.

In our study, the first to explore the prognostic performance of the mGPS in early-stage NSCLC, the score demonstrated suboptimal discriminatory ability, with patients grouped as being of intermediate risk (i.e., mGPS 1) not differing significantly from patients of poor risk (i.e., mGPS 2) in terms of OS. A number of studies have confirmed the mGPS as a valuable and objective tool to assess patient’s prognosis in advanced NSCLC (Forrest et al, 2005; Giannousi et al, 2012; Leung et al, 2012), with non-inferior accuracy to that of more established predictors such as performance status (Forrest et al, 2004). However, the lack of reproducibility that we found seems to suggest that the mGPS is a stage-dependent prognostic factor in NSCLC, as a likely result of worsening cachexia in advanced tumours, that is associated with hypoalbuminaemia and elevated CRP (Wallengren et al, 2013). The same is not true for the NLR, whose prognostic power is apparent in both localised (Tomita et al, 2011, 2012) and metastatic cases of NSCLC (Cedres et al, 2012; Yao et al, 2012).

In our study, the first to validate the NLR as a prognostic marker in early-stage NSCLC, we confirmed that an elevated NLR identifies patients with a poor prognostic outlook and a survival difference of almost 2 years compared to those with a normal score at diagnosis. Interestingly, such an effect on patient survival is independent of the tumour stage or other adverse pathological features including grade, LVI or VPI. Our results that confirm the accuracy of NLR as a prognostic predictor in early-stage NSCLC in a western patient group are consistent with the results obtained from an Asian population of 284 consecutive patients also with early-stage NSCLC (Tomita et al, 2011). This similarity in the findings comes despite the fact that the distribution of risk factors, pathogenic molecular alterations and clinical outcome are notably different in an Asian patient group.

In our comparative analysis of prognostic scores, we also tested the PLR, whose role in predicting patient’s survival had not been taken into consideration before in NSCLC. In our study, only a limited fraction of patients had an elevated PLR, with no significant impact on survival. An abnormal PLR has been previously noted to associate with increased risk of grade III/IV toxicity from systemic treatment in advanced NSCLC (Arrieta et al, 2010). Whether the PLR may have any prognostic role in inoperable tumours remains to be ascertained.

This is not the first study to support the prognostic validity of the systemic inflammatory response in cancer. In a previous study involving >12 000 patients, the NLR was found as a significant and accurate predictor of cancer-specific survival, independently of histotype and stage (Proctor et al, 2012). This observation follows growing evidence from a number of smaller, mostly single institution-based studies, which independently confirmed a prognostic role for inflammation-based indices in thoracic (Pinato et al, 2012a), gastrointestinal (Sharma et al, 2008b; Pinato et al, 2012b, 2012c; Wang et al, 2012), genitourinary malignancies (Hilmy et al, 2006; Ramsey et al, 2007) as well as in many others (Hilmy et al, 2006; Sharma et al, 2008a; Mohamed et al, 2014; Pinato et al, 2014). More recent evidence has shown that resolution of the systemic inflammatory response may reflect disease-modulating effects from locoregional and systemic anticancer therapies and predict for survival benefit from treatment (Kao et al, 2010; Chua et al, 2012; Pinato and Sharma, 2012).

The biological grounds justifying a prognostic role for systemic inflammation are however yet to be fully elucidated. It is well established that the symptomatic burden that is typically associated with progressive malignant disease specifically anorexia, weight loss, muscle wasting and adipose tissue depletion are part of a complex paraneoplastic derangement in metabolism driven by the excessive secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL) 6 (Batista et al, 2013), IL-8 and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Esper and Harb, 2005). Some of these mediators such as IL-6 retain direct antiapoptotic as well as pro-angiogenic effects, conferring survival advantage to proliferating tumour cells and promoting resistance to cytotoxic therapies (Guo et al, 2012). Moreover, the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokine excess, whether directly produced by the tumour or as part of the host’s innate response, can exert immunomodulatory effects by suppressing specific antitumour immune mechanisms (Elkord et al, 2010). T-cell function impairment, often paralleled by relative lymphopenia in the full blood count, is at least in part responsible for an increase in the NLR (Ray-Coquard et al, 2009).

To conclude, our study has validated the NLR as the only inflammation-based prognostic score in operable NSCLC. Interestingly, our study confirms TNM stage and VPI as predictors of OS, while stage and LVI emerged as risk factors for shortened time to relapse. Given the prospective nature of our study that included unselected consecutive referrals, the significant proportion of patients with <12 months follow-up, amounting to 48%, should be acknowledged as a limitation to our survival analysis, warranting independent validation of our findings in a separate data set. However, the level of statistical significance achieved for the prognostic traits tested in our series leaves little doubt about the reliability and reproducibility of our findings. The NLR is a proven objective, reproducible and inexpensive predictor of survival in both operable and advanced stage NSCLC and consideration should be given for its routine clinical use.

Change history

15 April 2014

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Arrieta O, Michel Ortega RM, Villanueva-Rodriguez G, Serna-Thome MG, Flores-Estrada D, Diaz-Romero C, Rodriguez CM, Martinez L, Sanchez-Lara K (2010) Association of nutritional status and serum albumin levels with development of toxicity in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with paclitaxel-cisplatin chemotherapy: a prospective study. BMC Cancer 10: 50.

Balkwill F, Mantovani A (2001) Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357 (9255): 539–545.

Batista ML Jr, Olivan M, Alcantara PS, Sandoval R, Peres SB, Neves RX, Silverio R, Maximiano LF, Otoch JP, Seelaender M (2013) Adipose tissue-derived factors as potential biomarkers in cachectic cancer patients. Cytokine 61 (2): 532–539.

Bremnes RM, Al-Shibli K, Donnem T, Sirera R, Al-Saad S, Andersen S, Stenvold H, Camps C, Busund LT (2011) The role of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and chronic inflammation at the tumor site on cancer development, progression, and prognosis: emphasis on non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 6 (4): 824–833.

Cedres S, Torrejon D, Martinez A, Martinez P, Navarro A, Zamora E, Mulet-Margalef N, Felip E (2012) Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as an indicator of poor prognosis in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 14 (11): 864–869.

Chua W, Clarke SJ, Charles KA (2012) Systemic inflammation and prediction of chemotherapy outcomes in patients receiving docetaxel for advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 20 (8): 1869–1874.

Dhillon T, Mauri FA, Bellezza G, Cagini L, Barbareschi M, North BV, Seckl MJ (2010) Overexpression of the mammalian target of rapamycin: a novel biomarker for poor survival in resected early stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 5 (3): 314–319.

Elkord E, Alcantar-Orozco EM, Dovedi SJ, Tran DQ, Hawkins RE, Gilham DE (2010) T regulatory cells in cancer: recent advances and therapeutic potential. Expert Opin Biol Ther 10 (11): 1573–1586.

Esper DH, Harb WA (2005) The cancer cachexia syndrome: a review of metabolic and clinical manifestations. Nutr Clin Pract 20 (4): 369–376.

Fibla JJ, Cassivi SD, Brunelli A, Decker PA, Allen MS, Darling GE, Landreneau RJ, Putnam JB (2012) Re-evaluation of the prognostic value of visceral pleura invasion in Stage IB non-small cell lung cancer using the prospective multicenter ACOSOG Z0030 trial data set. Lung Cancer 78 (3): 259–262.

Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dagg K, Scott HR (2005) A prospective longitudinal study of performance status, an inflammation-based score (GPS) and survival in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 92 (10): 1834–1836.

Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ (2004) Comparison of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) with performance status (ECOG) in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy for inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 90 (9): 1704–1706.

Gately K, Al-Alao B, Dhillon T, Mauri F, Cuffe S, Seckl M, O'Byrne K (2012) Overexpression of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and angioinvasion are poor prognostic factors in early stage NSCLC: a verification study. Lung Cancer 75 (2): 217–222.

Giannousi Z, Gioulbasanis I, Pallis AG, Xyrafas A, Dalliani D, Kalbakis K, Papadopoulos V, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V, Papandreou CN (2012) Nutritional status, acute phase response and depression in metastatic lung cancer patients: correlations and association prognosis. Support Care Cancer 20 (8): 1823–1829.

Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, Read W, Tierney R, Vlahiotis A, Spitznagel EL, Piccirillo J (2006) Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol 24 (28): 4539–4544.

Goya T, Asamura H, Yoshimura H, Kato H, Shimokata K, Tsuchiya R, Sohara Y, Miya T, Miyaoka E Japanese Joint Committee of Lung Cancer R (2005) Prognosis of 6644 resected non-small cell lung cancers in Japan: a Japanese lung cancer registry study. Lung Cancer 50 (2): 227–234.

Guo Y, Xu F, Lu T, Duan Z, Zhang Z (2012) Interleukin-6 signaling pathway in targeted therapy for cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 38 (7): 904–910.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144 (5): 646–674.

Hilmy M, Campbell R, Bartlett JM, McNicol AM, Underwood MA, McMillan DC (2006) The relationship between the systemic inflammatory response, tumour proliferative activity, T-lymphocytic infiltration and COX-2 expression and survival in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Br J Cancer 95 (9): 1234–1238.

Hung JJ, Wang CY, Huang MH, Huang BS, Hsu WH, Wu YC (2007) Prognostic factors in resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer with a diameter of 3 cm or less: visceral pleural invasion did not influence overall and disease-free survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 134 (3): 638–643.

Kao SC, Pavlakis N, Harvie R, Vardy JL, Boyer MJ, van Zandwijk N, Clarke SJ (2010) High blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an indicator of poor prognosis in malignant mesothelioma patients undergoing systemic therapy. Clin Cancer Res 16 (23): 5805–5813.

Leung EY, Scott HR, McMillan DC (2012) Clinical utility of the pretreatment glasgow prognostic score in patients with advanced inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 7 (4): 655–662.

Lopez Guerra JL, Gomez DR, Lin SH, Levy LB, Zhuang Y, Komaki R, Jaen J, Vaporciyan AA, Swisher SG, Cox JD, Liao Z, Rice DC (2013) Risk factors for local and regional recurrence in patients with resected N0-N1 non-small-cell lung cancer, with implications for patient selection for adjuvant radiation therapy. Ann Oncol 24 (1): 67–74.

McMillan DC (2012) The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score: A decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 39 (5): 534–540.

Mohamed Z, Pinato DJ, Mauri FA, Chen KW, Chang PM, Sharma R (2014) Inflammation as a validated prognostic determinant in carcinoma of unknown primary site. Br J Cancer 110 (1): 208–213.

Moore MM, Chua W, Charles KA, Clarke SJ (2010) Inflammation and cancer: causes and consequences. Clin Pharmacol Ther 87 (4): 504–508.

O'Callaghan DS, O'Donnell D, O'Connell F, O'Byrne KJ (2010) The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 5 (12): 2024–2036.

Ou SH, Ziogas A, Zell JA (2009) Asian ethnicity is a favorable prognostic factor for overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and is independent of smoking status. J Thorac Oncol 4 (9): 1083–1093.

Pinato DJ, Mauri FA, Ramakrishnan R, Wahab L, Lloyd T, Sharma R (2012a) Inflammation-based prognostic indices in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 7 (3): 587–594.

Pinato DJ, North BV, Sharma R (2012b) A novel, externally validated inflammation-based prognostic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma: the prognostic nutritional index (PNI). Br J Cancer 106 (8): 1439–1445.

Pinato DJ, Sharma R (2012) An inflammation-based prognostic index predicts survival advantage after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res 160 (2): 146–152.

Pinato DJ, Stavraka C, Flynn MJ, Forster MD, O'Cathail SM, Seckl MJ, Kristeleit RS, Olmos D, Turnbull SJ, Blagden SP (2014) An inflammation based score can optimize the selection of patients with advanced cancer considered for early phase clinical trials. PLoS One 9 (1): e83279.

Pinato DJ, Stebbing J, Ishizuka M, Khan SA, Wasan HS, North BV, Kubota K, Sharma R (2012c) A novel and validated prognostic index in hepatocellular carcinoma: the inflammation based index (IBI). J Hepatol 57 (5): 1013–1020.

Proctor MJ, McMillan DC, Morrison DS, Fletcher CD, Horgan PG, Clarke SJ (2012) A derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer 107 (4): 695–699.

Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, Balmer SM, Fletcher CD, O'Reilly DS, Foulis AK, Horgan PG, McMillan DC (2011) A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur J Cancer 47 (17): 2633–2641.

Ramsey S, Lamb GW, Aitchison M, Graham J, McMillan DC (2007) Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with metastatic renal cancer. Cancer 109 (2): 205–212.

Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, Sebban C, Le Cesne A, Judson I, Tredan O, Verweij J, Biron P, Labidi I, Guastalla JP, Bachelot T, Perol D, Chabaud S, Hogendoorn PC, Cassier P, Dufresne A, Blay JY (2009) Lymphopenia as a prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Cancer Res 69 (13): 5383–5391.

Sakurai H, Asamura H, Goya T, Eguchi K, Nakanishi Y, Sawabata N, Okumura M, Miyaoka E, Fujii Y Japanese Joint Committee for Lung Cancer R (2010) Survival differences by gender for resected non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis of 12,509 cases in a Japanese Lung Cancer Registry study. J Thorac Oncol 5 (10): 1594–1601.

Sequist LV, Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haber DA (2007) Molecular predictors of response to epidermal growth factor receptor antagonists in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 25 (5): 587–595.

Sharma R, Hook J, Kumar M, Gabra H (2008a) Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer 44 (2): 251–256.

Sharma R, Zucknick M, London R, Kacevska M, Liddle C, Clarke SJ (2008b) Systemic inflammatory response predicts prognosis in patients with advanced-stage colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 7 (5): 331–337.

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2012) Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 62 (1): 10–29.

Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C (2009) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours 7th edn. Wiley-Blackwell: New York, USA.

Tomita M, Shimizu T, Ayabe T, Nakamura K, Onitsuka T (2012) Elevated preoperative inflammatory markers based on neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and C-reactive protein predict poor survival in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 32 (8): 3535–3538.

Tomita M, Shimizu T, Ayabe T, Yonei A, Onitsuka T (2011) Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor after curative resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 31 (9): 2995–2998.

Wallengren O, Lundholm K, Bosaeus I (2013) Diagnostic criteria of cancer cachexia: relation to quality of life, exercise capacity and survival in unselected palliative care patients. Support Care Cancer 21 (6): 1569–1577.

Wang DS, Luo HY, Qiu MZ, Wang ZQ, Zhang DS, Wang FH, Li YH, Xu RH (2012) Comparison of the prognostic values of various inflammation based factors in patients with pancreatic cancer. Med Oncol 29 (5): 3092–3100.

Yao Y, Yuan D, Liu H, Gu X, Song Y (2012) Pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is associated with response to therapy and prognosis of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 62 (3): 471–479.

Acknowledgements

MJS is supported by the Imperial College Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre and Imperial NIHR Biomedical Research Centre grants. The funding sources did not have any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pinato, D., Shiner, R., Seckl, M. et al. Prognostic performance of inflammation-based prognostic indices in primary operable non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 110, 1930–1935 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.145

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.145

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A comparison of inflammation markers for predicting oncological outcomes after surgical resection of non-small-cell lung cancer: a validated analysis of 2,066 patients

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Inflammatory Risk Factors for Early Recurrence of Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Within One Year Following Curative Resection

World Journal of Surgery (2020)

-

Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) Predicts Poor Survival in Pancreatic Cancer Patients Undergoing Resection

Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery (2020)

-

Exploring the value of new preoperative inflammation prognostic score: white blood cell to hemoglobin for gastric adenocarcinoma patients

BMC Cancer (2019)

-

Preoperative biopsy does not affect postoperative outcomes of resectable non-small cell lung cancer

General Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2019)