Abstract

Context

Although insomnia is a frequent health complaint that is often treated with drugs, little is known about differences in treatment efficacy of various drug classes on objective versus subjective outcome measures.

Objective

Our aim was to compare treatment efficacy of classical benzodiazepines, benzodiazepine receptor agonists (zopiclone, zolpidem and zaleplon), antidepressants (including low-dose doxepin), neuropeptides, progesterone receptor antagonists, hormones, melatonin receptor agonists, antihistamines, antiepileptics, and narcotics addressing primary insomnia.

Data Sources

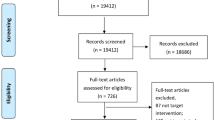

We conducted a comprehensive literature search (up to 5 April 2013) using PubMed, Cochrane Clinical Trials, PQDT OPEN, OpenGREY, ISI Web of Knowledge, PsycINFO, PSYNDEX, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

Eligibility Criteria

Only polysomnographic, parallel-group, randomized controlled drug trials were included; eligibility was determined by two independent authors.

Data Synthesis

We used a random effects model, based on 31 studies reporting 80 treatment conditions, covering 3,820 participants.

Results

Effect size estimates for the total sample of pooled drug classes suggest that there is a small-to-moderate, significant, and robust effect for objective outcomes (sleep onset latency g = −0.36, total sleep time g = 0.27) and subjective outcomes (sleep onset latency g = −0.24, total sleep time g = 0.21). Results indicate higher effect sizes for benzodiazepine receptor agonists and classical benzodiazepines compared with antidepressants (including low-dose doxepin) and for classical benzodiazepines compared with benzodiazepine receptor agonists. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists demonstrated higher effect sizes for objective outcomes.

Limitations

Data on drug safety were not analyzed.

Conclusions

Future studies should use objective and subjective assessment. Focusing on efficacy, clinicians should favor benzodiazepine receptor agonists and classical benzodiazepines over antidepressants (including low-dose doxepin) for primary insomnia treatment, but the additional consideration of different side effect profiles can lead to alternative treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Morin CM, Savard J, Ouellet M-C. Nature and treatment of insomnia. USA: Wiley; 2013. p. 318–39.

Leger D, Poursain B, Neubauer D, Uchiyama M. An international survey of sleeping problems in the general population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(1):307–17.

Roth T, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, Lakoma MD, Sampson NA, Shahly V, et al. Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition criteria: results from the America Insomnia Survey. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(6):592–600.

Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, Bialy L, Tubman M, Ospina M, et al. The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1335–50.

McCrae CS, Lichstein KL. Secondary insomnia: diagnostic challenges and intervention opportunities. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5(1):47–61. doi:10.1053/smrv.2000.0146.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Washington: APA; 2000.

Buysse DJ. Insomnia. JAMA. 2013;309(7):706–16.

Huedo-Medina TB, Kirsch I, Middlemass J, Klonizakis M, Siriwardena AN. Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2012;345:e8343.

Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1169–73. doi:10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47.

Dundar Y, Dodd S, Strobl J, Boland A, Dickson R, Walley T. Comparative efficacy of newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2004;19(5):305–22. doi:10.1002/hup.594.

Smith MT, Perlis ML, Park A, Smith MS, Pennington J, Giles DE et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):5–11.

Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;162(2):225–33.

Nowell PD, Mazumdar S, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, Reynolds CF 3rd, Kupfer DJ. Benzodiazepines and zolpidem for chronic insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. JAMA. 1997;278(24):2170–7.

Fernandez-San-Martin M, Masa-Font R, Palacios-Soler L, Sancho-Gomez P, Calbo-Caldentey C, Flores-Mateo G. Effectiveness of valerian on insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2010;11(6):505-11.

Liu J, Wang LN. Ramelteon in the treatment of chronic insomnia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(9):867–73. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02987.x.

Baldwin D. Short-term treatment with hypnotic drugs for insomnia: going beyond the evidence. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):134–5. doi:10.1177/0269881105051991.

JARS. Reporting standards for research in psychology: Why do we need them? What might they be? Am Psychol. 2008;63(9):839-51. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.9.839.

Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Lancet. 1999;354(9193):1896–900.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Cook DJ, Sackett DL, Spitzer WO. Methodologic guidelines for systematic reviews of randomized control trials in health care from the potsdam consultation on meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(1):167–71.

Morin CM. Measuring outcomes in randomized clinical trials of insomnia treatments. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(3):263–79. doi:10.1053/smrv.2002.0274.

Baglioni C, Regen W, Teghen A, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, Nissen C, et al. Sleep changes in the disorder of insomnia: a meta-analysis of polysomnographic studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(3):195–213. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2013.04.001.

Glass G. Primary, secondary and meta-analysis of research. Health Educ Res. 1976;5:3–8.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12.

Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comperhensive meta-analysis, version 2. 2nd ed. Engelwood: Biostat Inc.; 2005.

Hedges LV, Olkin I. Nonparametric estimators of effect size in meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1984;96(3):573–80. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.573.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1988.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63. doi:10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x.

Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1993.

Johnson BT, Eagly AH. Quantitative synthesis of social psychological research. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. London: Cambridge University Press; 2000. p. 496–528.

Rief W, Nestoriuc Y, Weiss S, Welzel E, Barsky AJ, Hofmann SG. Meta-analysis of the placebo response in antidepressant trials. J Affect Disord. 2009;118(1–3):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.029.

Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M. Placebo response in studies of major depression—variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA. 2002;287(14):1840–7. doi:10.1001/jama.287.14.1840.

Xu ZQ, Jiang XJ, Li W, Gao D, Li XJ, Liu J. Propofol-induced sleep: efficacy and safety in patients with refractory chronic primary insomnia. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;60(3):161–6. doi:10.1007/s12013-010-9135-7.

Mayer G, Wang-Weigand S, Roth-Schechter B, Lehmann R, Staner C, Partinen M. Efficacy and safety of 6-month nightly ramelteon administration in adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2009;32(3):351–60.

Randall S, Roehrs TA, Roth T. Efficacy of eight months of nightly zolpidem: a prospective placebo-controlled study. Sleep. 2012;35(11):1551–7. doi:10.5665/sleep.2208.

Riemann D, Nissen C. Substanzinduzierte Schlafstörungen und Schlafmittelmissbrauch. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2011;54(12):1325–31. doi:10.1007/s00103-011-1374-2.

Weinling E, McDougall S, Andre F, Bianchetti G, Dubruc C. Pharmacokinetic profile of a new modified release formulation of zolpidem designed to improve sleep maintenance. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2006;20(4):397–403. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00415.x.

Morin AK, Willett K. The role of eszopiclone in the treatment of insomnia. Adv Ther. 2009;26(5):500–18. doi:10.1007/s12325-009-0026-5.

Mitchell M, Gehrman P, Perlis M, Umscheid C. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):40.

Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, Bjorvatn B, Havik OE, Kvale G, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851–8. doi:10.1001/jama.295.24.2851.

Jacobs GD, Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R, Otto MW. Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial and direct comparison. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(17):1888–96. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.17.1888.

Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, Sood R, Brink D. Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;281(11):991–9.

Wu RG, Bao JF, Zhang CA, Deng J, Long CL. Comparison of sleep condition and sleep-related psychological activity after cognitive-behavior and pharmacological therapy for chronic insomnia. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(4):220–8. doi:10.1159/000092892.

McClusky H, Milby J, Switzer P, Williams V, Wooten V. Efficacy of behavioral versus triazolam treatment in persistent sleep-onset insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:121–6.

Bes F, Hofman W, Schuur J, Van Boxtel C. Effects of delta sleep-inducing peptide on sleep of chronic insomniac patients. A double-blind study. Neuropsychobiology. 1992;26(4):193–7. doi:118919.

Buckley T, Duggal V, Schatzberg AF. The acute and post-discontinuation effects of a glucocorticoid receptor (GR) antagonist probe on sleep and the HPA axis in chronic insomnia: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(3):235–41.

Fleming J, Moldofsky H, Walsh JK, Scharf M, Nino MG, Radonjic D. Comparison of the residual effects and efficacy of short term zolpidem, flurazepam and placebo in patients with chronic insomnia. Clin Drug Investig. 1995;9(6):303-313.

Hajak G, Rodenbeck A, Voderholzer U, Riemann D, Cohrs S, Hohagen F, et al. Doxepin in the treatment of primary insomnia: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, polysomnographic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(6):453–63. doi:10.4088/JCP.v62n0609.

Herrmann WM, Kubicki ST, Boden S, Eich FX, Attali P, Coquelin JP. Pilot controlled double-blind study of the hypnotic effects of zolpidem in patients with chronic ‘learned’ insomnia: psychometric and polysomnographic evaluation. J Int Med Res. 1993;21(6):306–22.

Krystal AD, Durrence HH, Scharf M, Jochelson P, Rogowski R, Ludington E, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg in a 12-week sleep laboratory and outpatient trial of elderly subjects with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2010;33(11):1553–61.

Krystal AD, Lankford A, Durrence HH, Ludington E, Jochelson P, Rogowski R, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 3 and 6 mg in a 35-day sleep laboratory trial in adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2011;34(10):1433–42. doi:10.5665/sleep.1294.

Luthringer R, Muzet M, Zisapel N, Staner L. The effect of prolonged-release melatonin on sleep measures and psychomotor performance in elderly patients with insomnia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(5):239–49. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832e9b08.

McCall WV, Erman M, Krystal AD, Rosenberg R, Scharf M, Zammit GK, et al. A polysomnography study of eszopiclone in elderly patients with insomnia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(9):1633–42. doi:10.1185/030079906x112741.

Monti JM, Alvarino F, Monti D. Conventional and power spectrum analysis of the effects of zolpidem on sleep EEG in patients with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2000;23(8):1075–84.

Monti JM, Attali P, Monti D, Zipfel A, de la Giclais B, Morselli PL. Zolpidem and rebound insomnia—a double-blind, controlled polysomnographic study in chronic insomniac patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1994;27(4):166–75. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1014298.

Monti JM, Monti D, Estevez F, Giusti M. Sleep in patients with chronic primary insomnia during long-term zolpidem administration and after its withdrawal. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(4):255–63. doi:10.1097/00004850-199612000-00007.

Morin CM, Koetter U, Bastien C, Ware JC, Wooten V. Valerian-hops combination and diphenhydramine for treating insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1465–71.

Riemann D, Voderholzer U, Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Hajak G, Ruether E, et al. Trimipramine in primary insomnia: results of a polysomnographic double-blind controlled study. Trimipramin bei primaerer Insomnie: ergebnisse einer polysomnographischen kontrollierten Doppel-Blind-Studie. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002;35:165–74.

Roth T, Soubrane C, Titeux L, Walsh JK. Efficacy and safety of zolpidem-MR: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adults with primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2006;7(5):397–406. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2006.04.008.

Roth T, Wright KP, Walsh J. Effect of tiagabine on sleep in elderly subjects with primary insomnia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sleep. 2006;29(3):335–41.

Roth TG, Roehrs TA, Koshorek GL, Greenblatt DJ, Rosenthal LD. Hypnotic effects of low doses of quazepam in older insomniacs. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997.

Scharf MB, Roth T, Vogel GW, Walsh JK. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating zolpidem in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(5):192–9.

Schulz H, Stolz C, Muller J. The effect of valerian extract on sleep polygraphy in poor sleepers—a pilot-study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1994;27(4):147–51. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1014295.

Walsh JK, Perlis M, Rosenthal M, Krystal A, Jiang J, Roth T. Tiagabine increases slow-wave sleep in a dose-dependent fashion without affecting traditional efficacy measures in adults with primary insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(1):35–41.

Walsh JK, Soubrane C, Roth T. Efficacy and safety of zolpidem extended release in elderly primary insomnia patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):44–57. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181256b01.

Walsh JK, Vogel GW, Scharf M, Erman M, Erwin CW, Schweitzer PK, et al. A five week, polysomnographic assessment of zaleplon 10 mg for the treatment of primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2000;1(1):41–9. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00006-4.

Ware J, Walsh JK, Scharf MB, Roehrs T, Roth T, Vogel GW. Minimal rebound insomnia after treatment with 10-mg zolpidem. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20(2):116–25. doi:10.1097/00002826-199704000-00002.

Zammit G, Erman M, Wang-Weigand S, Sainati S, Zhang J, Roth T. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of ramelteon in subjects with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):495–504.

Zammit GK, McNabb LJ, Caron J, Amato DA, Roth T. Efficacy and safety of eszopiclone across 6-weeks of treatment for primary insomnia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;. doi:10.1185/174234304X15174.

Enck P, Bingel U, Schedlowski M, Rief W. The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):191–204. doi:10.1038/nrd3923.

Acknowledgments and Funding

The study was prepared in the context of the FOR 1328 research unit on placebo and nocebo mechanisms and was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG). A Winkler, C Auer, BK Doering, and W Rief have no conflicts of interest including any financial, personal, or other relationships with other people or organizations to declare that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, the present work. This study did not require ethics approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Detailed Information on Quantitative Data Synthesis and Moderator Analyses

Since comparative effectiveness research (CER) trials result in a higher clinical efficacy of the drug compared with conventional placebo-controlled trials [74], we decided a priori to restrict the searches to placebo-controlled trials.

The intergroup effect sizes were computed using the following formula: \( d = \frac{{\bar{X}_{1} - \bar{X}_{2} }}{{\sqrt {\frac{{\left( {n_{1} - 1} \right) S_{1}^{2} + \left( {n_{2} - 1} \right) S_{2}^{2} }}{{n_{1} + n_{2} - 2}}} }} \), where \( \bar{X}_{1} \) and \( \bar{X}_{2} \) are the sample means, \( S_{1} \) and \( S_{2} \) are the SDs, and \( n_{1} \) and \( n_{2} \) are the sample sizes in the intervention condition and the control condition, respectively.

For studies reporting mean change, SD difference, and N in each group, the intergroup effect size was calculated using the following formula: \( d = \frac{{\bar{X}_{1} - \bar{X}_{2} }}{{\sqrt {\frac{{\left( {n_{1} - 1} \right) S_{1}^{2} + \left( {n_{2} - 1} \right) S_{2}^{2} }}{{n_{1} + n_{2} - 2}}} }} \), where \( \bar{X}_{1} \) and \( \bar{X}_{2} \) are the sample mean changes, \( n_{1} \) and \( n_{2} \) are the sample sizes in the intervention condition and the control condition, respectively, and \( S_{1} \) and \( S_{2} \) are the SDs determined by the following formula: \( S_{x} = \frac{{{\text{SD change}}_{x} }}{{\sqrt {2 (1 - r)} }} \), where SD change x is the given SD change and r is the pre-post correlation. To calculate controlled effect sizes, the correlation between pre- and post-treatment measures is called for; however, it could not be determined from the study reports. As recommended by Rosenthal [33], we used a conservative estimate of r = 0.70 instead.

Hedges’ g can be computed by multiplying d by a correction factor \( J = 1 - \frac{3}{4df - 1} \), where df is the degrees of freedom to estimate the intra-group SD.

Q is determined by the following formula: \( Q = \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{k} {W_{i} Y_{i}^{2} } - \frac{{\left( {\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{k} {W_{i} Y_{i} } } \right)}}{{\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{k} {W_{i} } }} \), with W i being the weight of the study, Y i the effect size of the study, and k the number of studies included. To determine the expected value of Q, we used the degrees of freedom (\( df = k - 1 \), with k being the number of studies included). A significant Q test (p value less than alpha set at 0.05) indicates heterogeneity in effect sizes.

I 2 is determined by using the following formula: \( I^{2} = \left( {\frac{Q - df}{Q}} \right) \times 100\;\% \). I 2 is expressed as a ratio, with a range of 0–100 %, and describes what proportion of the observed variance reflects real differences in effect sizes. Higgins et al. [30] suggest that values of 25, 50, and 75 % can be considered as low, moderate, and high, respectively.

We computed the fail-safe N using the following formula: \( X = \frac{{K(K\bar{Z}^{2} - 2.706)}}{2.706} \), where K is the number of studies in the meta-analysis and \( \bar{Z} \) is the mean Z obtained from the K studies. The effect size can be characterized as robust if the number of studies (X) required to reduce the overall effect size to a non-significant level exceeds 5K + 10 [33].

We used the Trim and Fill method, which examines whether negative or positive trials are over- or under-represented, depending on the sample size. This information can then be used to re-calculate the effect size estimates, if the funnel plot is asymmetric. The divergence of the original effect size and the re-calculated effect size shows the degree of robustness of the results.

Instead of conducting a power analysis, we report the observed effect size with its CI, which is more informative than the statement that power was low [31]. We also did not report Ms and SDs for measurement artifacts because construct-level relationships were not the focus of this analysis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Winkler, A., Auer, C., Doering, B.K. et al. Drug Treatment of Primary Insomnia: A Meta-Analysis of Polysomnographic Randomized Controlled Trials. CNS Drugs 28, 799–816 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-014-0198-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-014-0198-7