Abstract

Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is an acute form of brain inflammation that is potentially lethal but has a high probability for recovery with treatment. Although the clinical picture of anti-NMDAR encephalitis is usually recognizable due to its relatively well-known symptoms, the disorder can sometimes present itself in an unpredictable and atypical way. In this case report, we wish to present the influence of different delay times prior to the establishment of diagnosis. Thus, our first patient was diagnosed with anti-NMDAR encephalitis 4 years after the initial symptoms, the second one after 8 years, and the third one after 13 months. The outcomes of the three presented patients indicate the importance of being aware of many clinical presentations of this disorder, as its early diagnosis greatly affects the outcome and may reduce permanent damage, especially in cognitive functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Anti-N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the presence of specific IgG antibodies against heteromers of NR1 and NR2 subunits of cell-surface NMDA receptors which can be found in serum or cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). Although it can be a pure autoimmune disorder, anti-NMDAR encephalitis is frequently associated with an underlying malignancy, commonly occult ovarian teratoma (Titulaer et al. 2013). The disease symptoms are relatively well-known and in the majority of cases, it usually has a good outcome (Graus et al. 2016; Dalmau et al. 2011). However, clinical picture of this multiphasic disorder can sometimes be unpredictable and atypical, leading to a delay in the diagnosis establishment. It is usually evident in encephalitis presenting exclusively with psychiatric symptoms. The major problem is a lack of the characteristic ones that would imply the need for specific antibody testing, which usually leads to prolonged and more demanding treatment with increased tendency of worse outcome, cognitive impairment, and unpredictable relapses (Herken and Pruss 2017; Kayser et al. 2013).

We are presenting three case reports with different time lapse to diagnosis establishment and successfulness of immunosuppression treatment.

Case report 1

At the age of 17, a female patient was admitted to a psychiatry clinic due to psychomotor agitation, anxiety, disorganization of thoughts, logorrhea, cognitive impairment, visual and auditory hallucinations, and insomnia. In spite of initiated antipsychotic therapy (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, clozapine, and sodium valproate), she developed catatonia and incontinence. Her EEG recording showed predominant beta activity and brain MRI was unremarkable, while CSF tests revealed mild pleocytosis (55/3) with lymphocyte predomination. On haloperidol and later ziprasidone, her psychiatric condition ameliorated and for the next 4 years, she was in remission. At the age of 21, she developed relapse characterized by auditory hallucinations, insomnia, disorganized behavior, and psychomotor agitation with fever and elevated creatine kinase. Soon after, she also developed quantitative disorder of consciousness, generalized tonic-clonic seizures that were treated successfully with levetiracetam, autonomic dysfunction, and respiratory insufficiency. At that point, NMDAR antibodies were isolated both in serum and CSF. Corticosteroid therapy followed by plasmapheresis was conducted without any significant improvement and still in need of mechanical ventilation. The induction of cyclophosphamide led to complete symptom resolution and 2 years after, she is still seizure free and without any symptoms (mRS 0).

Case report 2

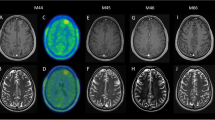

Nineteen-year-old patient was admitted to our Department of Neurology due to status epilepticus. Her previous medical history revealed frequent hospitalizations in pediatric intensive care unit due to status epilepticus, prolonged disorder of consciousness, respiratory insufficiency, autonomic instability with sometimes cognitive impairment, language difficulties, and associated dyskinesias. In the 8-year-period, she has been hospitalized approximately once a year. Although extensive diagnostic workup was conducted, no etiological factor was found. During that period, she was treated with corticosteroid therapy but there was no clear data of their effectiveness and no other immunosuppressive treatment was applied. At the admission to our hospital, she was in convulsive status epilepticus with autonomic dysfunction and in need of mechanical ventilation. Brain MRI showed unspecific T2 and FLAIR hyperintensities (Fig. 1) and additional workup revealed NMDAR antibodies in serum and CSF. She was treated with corticosteroid therapy followed by six cycles of intravenous immunoglobulin and, at last, cyclophosphamide, which led to resolution of status epilepticus and other aforementioned symptoms. In a 4-year period, there was no disease relapse, but she still has focal seizures, despite three antiepileptic drugs (oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, and clobazam), as well as mild cognitive impairment (mRS 1).

Case report 3

Our third patient had focal aware sensory and cognitive (vertiginous sensations, blurring of vision, derealization, and depersonalization) seizures with interictal concentration and behavior changes since the age of 16. Her brain MRI showed T2 and FLAIR hyperintensity in the left temporal lobe (Fig. 2), CSF pleocytosis, type II oligoclonal bands, and left temporal focal EEG changes. After including oxcarbazepine in the therapy, her seizures were under control as were her psychiatric symptoms. Diagnostic workup revealed no etiological factor of her condition. Brain MRI conducted 3 months later was without any pathological changes. After 8 months, her seizures started again, this time with evolution to bilateral tonic-clonic convulsions. Repeated brain MRI was unremarkable (Fig. 3) as was EEG recording. CSF analysis was still showing type II oligoclonal bands. In the next few weeks, she experienced cognitive and psychic deterioration (disorientation in time and space, inadequacy in contact without understanding of instructions, she was hostile and had dissociated thoughts with confabulations, inadequate answers, difficulties in reconstruction of events, delusions, and deterioration of cognitive functions). During the 2 months period, a large number of typical and atypical antipsychotics were used without any improvement. She was then transferred to our department and corticosteroid therapy was started with mild improvement of mental functions, but with persistent epileptic seizures. After proving NMDAR antibodies in serum and CSF, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy was started in combination with oxcarbazepine, with complete resolution of symptoms (mRS 0). She is without relapse for more than 1 year now.

In neither of three patients, malignancy was found on frequent controls according to Bonn protocol (Bien and Elger 2007).

Discussion and conclusion

In our three patients, anti-NMDAR encephalitis was diagnosed one or more years after the initial presentation. Symptomatology, disease progression, MRI findings, and frequency and time of relapses were different in all three cases. The most common cause of prolonged time to diagnosis establishment is unawareness of psychiatric symptoms as possible initial presentation of anti-NMDAR encephalitis. It is widely known that 77% of patients are initially presented with psychiatric changes (Herken and Pruss 2017; Dalmau et al. 2008; Barry et al. 2011; Chapman and Vause 2011; Lejuste et al. 2016). Psychiatric symptoms were initially present in our three patients, being the dominant symptom in the two of them. Relapses have been reported in approximately 10–29% of anti-NMDAR encephalitis cases, being more common in patients without malignancies, which was also the case in our three patients (Titulaer et al. 2013; Dalmau et al. 2011; Irani et al. 2011).

Although randomized controlled trials of anti-NMDAR encephalitis therapy are yet to be conducted, large retrospective studies suggest that good prognosis, including fewer relapses, is associated with early diagnosis and treatment, milder symptoms, and removal of tumor when present (Dalmau et al. 2011; Irani et al. 2011; Gabilondo et al. 2011). In our three cases, relapses were present in different time intervals without adequate immunosuppressive treatment. The first patient had relapse few years after the initial presentation while the other one had disease outbreak before the discovery of specific antibodies. In the third case, relapses occurred despite the withdrawal of changes in brain MRI. In all the cases, corticosteroid therapy was inadequate as a first line of treatment in relapses. The administration of immunoglobulin, cyclophosphamide, or rituximab was necessary. In correlation with other studies, it is possible that early administration of immunoglobulin therapy or plasmapheresis could have better results and prevent relapses (Titulaer et al. 2013; Gabilondo et al. 2011; Barry et al. 2015; Venkatesan and Adatia 2017). Late diagnosis establishment can probably cause permanent damage especially in cognitive functions (McKneon et al. 2018; Finke et al. 2018). In spite of delayed diagnosis in our case series, there was no permanent cognitive damage in two patients and the third one with frequent relapses had mild cognitive impairment and pharmacoresistant seizures. The permanent cognitive damage is probably due to repetitive status epilepticus, longer disease duration, and more frequent relapses (Sutter et al. 2013; Lergiel et al. 2008).

All three cases had beneficial outcome in spite of delayed diagnostic process which could be due to the lack of the underlying malignancy or to a natural history of the disease which can sometimes be benign. Nevertheless, the timely diagnosis establishment is of the highest priority, considering that early treatment could prevent progression to consciousness impairment, autonomic dysfunction, respiratory insufficiency, and the need for intensive care unit treatment (de Montmollin et al. 2017).

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis can have different initial presentations, disease course, relapse frequency, treatment response, and outcome. The recognition of the aforementioned variations can help in timely and adequate treatment administration and improve the final outcome of anti-NMDAR encephalitis patients.

References

Barry H, Hardiman O, Healz DG, Keogan M, Moroney J, Molnar PP, Cotter DR, Murphy KC (2011) Anti NMDA receptor encephalits: an important differential diagnosis in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 199(6):508–509. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092197

Barry H, Byrne S, Barrett E, Murphy KC, Cotter DR (2015) Anti-N-methyl D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. BJPsych Bull 39(1):19–23. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.113.045518

Bien CG, Elger CE (2007) Limbic encephalitis: a cause of temporal lobe epilepsy with onset in adult life. Epilepsy Behav 10(4):529–538

Chapman MR, Vause HE (2011) Anti NMDA receptor encephalitis: diagnosis, psychiatric presentation, and treatment. Am J Psychiatry 168(3):245–251. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020181

Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Huges EG, Rossi JE, Peng X, Lai M, Dessain SK, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R, Lynch DR (2008) Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol 7(12):1091–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70224-2

Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R (2011) Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 10(1):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70253-2

de Montmollin E, Demeret S, Brulé N, Conrad M, Dailler F, Lerolle N, Navellou JC, Schwebel C, Alves M, Cour M, Engrand N, Tonnelier JM, Maury E, Ruckly S, Picard G, Rogemond V, Magalhaes É, Sharshar T, Timsit JF, Honnorat J, Sonneville R (2017) Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis in adult patients requiring intensive care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195(4):491–499. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201603-0507OC

Finke C, Kopp UA, Pruss H, Dalmau J, Wandinger K-P, Ploner CJ (2018) Cognitive deficits following anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 40(3):234–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2017.1329408

Gabilondo I, Saiz A, Galan L, González V, Jadraque R, Sabater L, Sans A, Sempere A, Vela A, Villalobos F, Viñals M, Villoslada P, Graus F (2011) Analysis of relapses in anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurology 77(10):996–999. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822cfc6b

Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, Benseler S, Bien CG, Cellucci T, Cortese I, Dale RC, Gelfand JM, Geschwind M, Glaser CA, Honnorat J, Höftberger R, Iizuka T, Irani SR, Lancaster E, Leypoldt F, Prüss H, Rae-Grant A, Reindl M, Rosenfeld MR, Rostásy K, Saiz A, Venkatesan A, Vincent A, Wandinger KP, Waters P, Dalmau J (2016) A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 15(4):391–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9

Herken J, Pruss H (2017) Red flags: clinical signs for identifying autoimmune encephalits in psychiatric patients. Front Psychiatry 8:25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00025

Irani SR, Bera L, Waters P, González V, Jadraque R, Sabater L, Sans A, Sempere A, Vela A, Villalobos F, Viñals M, Villoslada P, Graus F (2011) N-methyl-D-asparatate receptor (NMDAR) encephalits: temporal progression of clinical and paraclinical observations in a predominantly non paraneoplastic disorders of both sexes. Neurology 77(10):996–999. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822cfc6b

Kayser MS, Titulaer MJ, Gresa-Arribas N, Dalmau J (2013) Frequency and characteristics of isolated psychiatric episodes in anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol 70(9):1133–1139

Lejuste F, Thomas L, Picard G, Desestret V, Ducray F, Rogemond V, Psimaras D, Antoine JC, Delattre JY, Groc L, Leboyer M, Honnorat J (2016) Neuroleptic intolerance in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 3(5):e280. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000280

Lergiel S, Mourvillier B, Bele N, Amro J, Fouet P, Manet P, Hilpert F (2008) Outcomes in 140 critically ill patients with status epilepticus. Intensive Care Med 34(3):476–480

McKneon GL, Robinson GA, Ryan AE, Blum S, Gillis D, Finke C, Scott JG (2018) Cognitive outcomes following anti N-methyl-D-aspratate receptor encephaltis: a systematic review. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 40(3):234–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2017.1329408

Sutter R, Marsch S, Fuhr P, Rüegg S (2013) Mortality and recovery from refractory status epilepticus in the intensive care unit: a 7-year observational study. Epilepsia 54(3):502–511

Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, Armangué T, Glaser C, Iizuka T, Honig LS, Benseler SM, Kawachi I, Martinez-Hernandez E, Aguilar E, Gresa-Arribas N, Ryan-Florance N, Torrents A, Saiz A, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R, Graus F, Dalmau J (2013) Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-N-methyl-D-aspratate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis: a cohort study. Lancet Neurol 12:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1

Venkatesan A, Adatia K (2017) Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: from bench to clinic. ACS Chem Neurosci 8(12):2586–2595. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00319

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS and ZPG prepared the case report. ZPG, SN, and VS are consultant neurologist responsible for the care of the patients. MS has been consulted as a specialist in infectious diseases and intensive medicine. DB and FD are responsible for the reference managing and preparing the text for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sulentic, V., Petelin Gadze, Z., Derke, F. et al. The effect of delayed anti-NMDAR encephalitis recognition on disease outcome. J. Neurovirol. 24, 638–641 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-018-0648-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-018-0648-y