Opinion statement

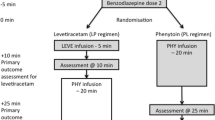

Convulsive status epilepticus (CSE) is a medical emergency with an associated high mortality and morbidity. It is defined as a convulsive seizure lasting more than 5 min or consecutive seizures without recovery of consciousness. Successful management of CSE depends on rapid administration of adequate doses of anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs). The exact choice of AED is less important than rapid treatment and early consideration of reversible etiologies. Current guidelines recommend the use of benzodiazepines (BNZ) as first-line treatment in CSE. Midazolam is effective and safe in the pre-hospital or home setting when administered intramuscularly (best evidence), buccally, or nasally (the latter two possibly faster acting than intramuscular (IM) but with lower levels of evidence). Regular use of home rescue medications such as nasal/buccal midazolam by patients and caregivers for prolonged seizures and seizure clusters may prevent SE, prevent emergency room visits, improve quality of life, and lower health care costs. Traditionally, phenytoin is the preferred second-line agent in treating CSE, but it is limited by hypotension, potential arrhythmias, allergies, drug interactions, and problems from extravasation. Intravenous valproate is an effective and safe alternative to phenytoin. Valproate is loaded intravenously rapidly and more safely than phenytoin, has broad-spectrum efficacy, and fewer acute side effects. Levetiracetam and lacosamide are well tolerated intravenous (IV) AEDs with fewer interactions, allergies, and contraindications, making them potentially attractive as second- or third-line agents in treating CSE. However, data are limited on their efficacy in CSE. Ketamine is probably effective in treating refractory CSE (RCSE), and may warrant earlier use; this requires further study. CSE should be treated aggressively and quickly, with confirmation of treatment success with epileptiform electroencephalographic (EEG), as a transition to non-convulsive status epilepticus is common. If the patient is not fully awake, EEG should be continued for at least 24 h. How aggressively to treat refractory non-convulsive SE (NCSE) or intermittent non-convulsive seizures is less clear and requires additional study. Refractory SE (RSE) usually requires anesthetic doses of anti-seizure medications. If an auto-immune or paraneoplastic etiology is suspected or no etiology can be identified (as with cryptogenic new onset refractory status epilepticus, known as NORSE), early treatment with immuno-modulatory agents is now recommended by many experts.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Trinka E et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus—report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1515–23. Comprehensive review of seizure types and definitions by world experts.

DeLorenzo RJ et al. Persistent nonconvulsive status epilepticus after the control of convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1998;39(8):833–40.

Treiman DM et al. A comparison of four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Veterans Affairs Status Epilepticus Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(12):792–8.

DeLorenzo RJ et al. A prospective, population-based epidemiologic study of status epilepticus in Richmond. Virginia Neurol. 1996;46(4):1029–35.

Hesdorffer DC et al. Incidence of status epilepticus in Rochester, Minnesota, 1965–1984. Neurology. 1998;50(3):735–41.

Logroscino G et al. Time trends in incidence, mortality, and case-fatality after first episode of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2001;42(8):1031–5.

Betjemann JP, Lowenstein DH. Status epilepticus in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(6):615–24.

Dham BS, Hunter K, Rincon F. The epidemiology of status epilepticus in the United States. Neurocrit Care. 2014;20(3):476–83.

Logroscino G et al. Short-term mortality after a first episode of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1997;38(12):1344–9.

Logroscino G et al. Mortality after a first episode of status epilepticus in the United States and Europe. Epilepsia. 2005;46 Suppl 11:46–8.

Rossetti AO, Lowenstein DH. Management of refractory status epilepticus in adults: still more questions than answers. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(10):922–30.

Foreman B, Hirsch LJ. Epilepsy emergencies: diagnosis and management. Neurol Clin. 2012;30(1):11–41. vii.

Belcour D et al. Prevalence and risk factors of stress cardiomyopathy after convulsive status epilepticus in ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(10):2164–70.

Kalviainen R. Intranasal therapies for acute seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:303–6.

Manno EM et al. Cardiac pathology in status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(6):954–7.

Vooturi S et al. Prognosis and predictors of outcome of refractory generalized convulsive status epilepticus in adults treated in neurointensive care unit. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;126:7–10.

Kapur J, Macdonald RL. Rapid seizure-induced reduction of benzodiazepine and Zn2+ sensitivity of hippocampal dentate granule cell GABAA receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17(19):7532–40.

Hillman J et al. Clinical significance of treatment delay in status epilepticus. Int J Emerg Med. 2013;6(1):6.

Alldredge BK et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):631–7.

Brophy GM et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):3–23. Provides the standard evidence based guidelines in managing SE, from the Neurocritical Care Society.

Shorvon S, Ferlisi M. The treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus: a critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 10):2802–18.

Silbergleit R et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):591–600. Provides class 1 evidence supporting treatment of SE with IM midazolam. Underscores the importance of rapid administration of anti-epileptic medications.

Misra UK, Kalita J, Maurya PK. Levetiracetam versus lorazepam in status epilepticus: a randomized, open labeled pilot study. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):645–8. A prospective, randomized study pitting lorazepam versus levetiracetam as first line treatment of SE. Authors found levetiracetam to be similiarly effective as lorazepam. This study needs to be replicated.

Gillies D et al. Benzodiazepines alone or in combination with antipsychotic drugs for acute psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD003079.

Ameer B, Greenblatt DJ. Lorazepam: a review of its clinical pharmacological properties and therapeutic uses. Drugs. 1981;21(3):162–200.

Leppik IE et al. Double-blind study of lorazepam and diazepam in status epilepticus. JAMA. 1983;249(11):1452–4.

Verrotti A et al. The adverse event profile of levetiracetam: a meta-analysis on children and adults. Seizure. 2015;31:49–55.

Brigo F et al. A common reference-based indirect comparison meta-analysis of buccal versus intranasal midazolam for early status epilepticus. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(9):741–57.

Shafer A. Complications of sedation with midazolam in the intensive care unit and a comparison with other sedative regimens. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(5):947–56.

Zhou Y et al. Midazolam and propofol used alone or sequentially for long-term sedation in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective, randomized study. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):R122.

Spina SP, Ensom MH. Clinical pharmacokinetic monitoring of midazolam in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(3):389–98.

Devlin JW, Mallow-Corbett S, Riker RR. Adverse drug events associated with the use of analgesics, sedatives, and antipsychotics in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(6 Suppl):S231–43.

De Winter S et al. Impact of temperature exposure on stability of drugs in a real-world out-of-hospital setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(4):380–7. e1.

Welch RD et al. Intramuscular midazolam versus intravenous lorazepam for the prehospital treatment of status epilepticus in the pediatric population. Epilepsia. 2015;56(2):254–62.

Arya R et al. Efficacy of nonvenous medications for acute convulsive seizures: a network meta-analysis. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1859–68. Interesting analysis of available non-venous treatment modalities for acute convulsive seizures. Adds to the building evidence supporting the use of intranasal or buccal midazolam in this setting.

Brigo F et al. Nonintravenous midazolam versus intravenous or rectal diazepam for the treatment of early status epilepticus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:325–36.

Inokuchi R et al. Comparison of intranasal and intravenous diazepam on status epilepticus in stroke patients: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(7):e555.

Gibbons RJ et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical practice guidelines: part I: where do they come from? Circulation. 2003;107(23):2979–86.

Misra UK, Kalita J, Patel R. Sodium valproate vs phenytoin in status epilepticus: a pilot study. Neurology. 2006;67(2):340–2.

Agarwal P et al. Randomized study of intravenous valproate and phenytoin in status epilepticus. Seizure. 2007;16(6):527–32.

Chakravarthi S et al. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin in management of status epilepticus. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(6):959–63.

Malamiri RA et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous sodium valproate versus phenobarbital in controlling convulsive status epilepticus and acute prolonged convulsive seizures in children: a randomised trial. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2012;16(5):536–41.

Mundlamuri RC et al. Management of generalised convulsive status epilepticus (SE): a prospective randomised controlled study of combined treatment with intravenous lorazepam with either phenytoin, sodium valproate or levetiracetam—pilot study. Epilepsy Res. 2015;114:52–8.

Yasiry Z, Shorvon SD. The relative effectiveness of five antiepileptic drugs in treatment of benzodiazepine-resistant convulsive status epilepticus: a meta-analysis of published studies. Seizure. 2014;23(3):167–74. Interesting meta-analysis with strict inclusion criteria. Authors concluded that phenytoin should not be considered before valproic acid, levetiracetam and phenobarbital in the treatment of RSE.

Rogawski MA, Loscher W. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(7):553–64.

Perucca P, Gilliam FG. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(9):792–802.

Frend V, Chetty M. Dosing and therapeutic monitoring of phenytoin in young adults after neurotrauma: are current practices relevant? Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30(6):362–9.

Cook AM et al. Practice variations in the management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):24–30.

Kay HY et al. M-current preservation contributes to anticonvulsant effects of valproic acid. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(10):3904–14.

Alvarez V et al. Second-line status epilepticus treatment: comparison of phenytoin, valproate, and levetiracetam. Epilepsia. 2011;52(7):1292–6.

Limdi NA et al. Efficacy of rapid IV administration of valproic acid for status epilepticus. Neurology. 2005;64(2):353–5.

Nanau RM, Neuman MG. Adverse drug reactions induced by valproic acid. Clin Biochem. 2013;46(15):1323–38.

Knudsen JF, Sokol GH, Flowers CM. Adjunctive topiramate enhances the risk of hypothermia associated with valproic acid therapy. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33(5):513–9.

Hernandez-Diaz S et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Neurology. 2012;78(21):1692–9.

Brigo F et al. IV Valproate in generalized convulsive status epilepticus: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(9):1180–91.

Rogawski MA. Diverse mechanisms of antiepileptic drugs in the development pipeline. Epilepsy Res. 2006;69(3):273–94.

Garcia-Perez E et al. Levetiracetam accelerates the onset of supply rate depression in synaptic vesicle trafficking. Epilepsia. 2015;56(4):535–45.

Patsalos PN. Pharmacokinetic profile of levetiracetam: toward ideal characteristics. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85(2):77–85.

Atmaca MM et al. Intravenous levetiracetam treatment in status epilepticus: a prospective study. Epilepsy Res. 2015;114:13–22.

Loscher W, Rogawski MA. How theories evolved concerning the mechanism of action of barbiturates. Epilepsia. 2012;53 Suppl 8:12–25.

Bledsoe KA, Kramer AH. Propylene glycol toxicity complicating use of barbiturate coma. Neurocrit Care. 2008;9(1):122–4.

Brigo F et al. A common reference-based indirect comparison meta-analysis of intravenous valproate versus intravenous phenobarbitone for convulsive status epilepticus. Epileptic Disord. 2013;15(3):314–23.

Rogawski MA et al. Current understanding of the mechanism of action of the antiepileptic drug lacosamide. Epilepsy Res. 2015;110:189–205.

Cross SA, Curran MP. Lacosamide: in partial-onset seizures. Drugs. 2009;69(4):449–59.

Kropeit D et al. Lacosamide cardiac safety: a thorough QT/QTc trial in healthy volunteers. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(5):346–54.

Hofler J, Trinka E. Lacosamide as a new treatment option in status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2013;54(3):393–404.

Kellinghaus C, Berning S, Stogbauer F. Intravenous lacosamide or phenytoin for treatment of refractory status epilepticus. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;129(5):294–9.

Miro J et al. Efficacy of intravenous lacosamide as an add-on treatment in refractory status epilepticus: a multicentric prospective study. Seizure. 2013;22(1):77–9.

Husain A. The TRENdS trial: Intravenous lacosamide versus fosphenytoin for the treatment of frequent nonconvulsive seizures in critically ill patients. Late breaking abstract American Epilepsy Society 2015, 2015.

Moseley BD, Degiorgio CM. Refractory status epilepticus treated with trigeminal nerve stimulation. Epilepsy Res. 2014;108(3):600–3.

Rossetti AO. Which anesthetic should be used in the treatment of refractory status epilepticus? Epilepsia. 2007;48 Suppl 8:52–5.

Fernandez A et al. High-dose midazolam infusion for refractory status epilepticus. Neurology. 2014;82(4):359–65. Provides evidence supporting high dose midazolam in treating RSE. Showed better outcomes in the high dose midazolam group, and shed light on the safety profile at such high doses.

Marik PE. Propofol: therapeutic indications and side-effects. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(29):3639–49.

Matta JA et al. General anesthetics activate a nociceptive ion channel to enhance pain and inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(25):8784–9.

Robinson BJ et al. Mechanisms whereby propofol mediates peripheral vasodilation in humans. Sympathoinhibition or direct vascular relaxation? Anesthesiology. 1997;86(1):64–72.

Bayrlee A et al. Treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15(10):66.

Yan J, Jiang H. Dual effects of ketamine: neurotoxicity versus neuroprotection in anesthesia for the developing brain. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26(2):155–60.

Gaspard N et al. Intravenous ketamine for the treatment of refractory status epilepticus: a retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2013;54(8):1498–503. Although retrospective, this large multicenter study found ketamine to be relatively safe and somewhat effective for treating RSE.

Ilvento L et al. Ketamine in refractory convulsive status epilepticus in children avoids endotracheal intubation. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:343–6.

Zeiler FA et al. Lidocaine for status epilepticus in adults. Seizure. 2015;31:41–8.

Achar S, Kundu S. Principles of office anesthesia: part I. Infiltrative anesthesia. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(1):91–4.

Peixoto RD, Hawley P. Intravenous lidocaine for cancer pain without electrocardiographic monitoring: a retrospective review. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(4):373–7.

Forrence E, Covinsky JO, Mullen C. A seizure induced by concurrent lidocaine-tocainide therapy—is it just a case of additive toxicity? Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1986;20(1):56–9.

Gaspard N et al. New-onset refractory status epilepticus: etiology, clinical features, and outcome. Neurology. 2015;85(18):1604–13. Reviews the clinical features of NORSE and highlights its diverse etiologies, especially autoimmune.

Khawaja AM et al. New-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE)—the potential role for immunotherapy. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;47:17–23.

Lopinto-Khoury C, Sperling MR. Autoimmune status epilepticus. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013;15(5):545–56.

Broomall E et al. Pediatric super-refractory status epilepticus treated with allopregnanolone. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(6):911–5.

Hottinger A et al. Topiramate as an adjunctive treatment in patients with refractory status epilepticus: an observational cohort study. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):761–72.

Asadi-Pooya AA et al. Treatment of refractory generalized convulsive status epilepticus with enteral topiramate in resource limited settings. Seizure. 2015;24:114–7.

Rohracher A et al. Perampanel in patients with refractory and super-refractory status epilepticus in a neurological intensive care unit. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:354–8.

Redecker J et al. Efficacy of perampanel in refractory nonconvulsive status epilepticus and simple partial status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;45:176–9.

Rantsch K et al. Treatment and course of different subtypes of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2013;107(1–2):156–62.

Alvarez V et al. Practice variability and efficacy of clonazepam, lorazepam, and midazolam in status epilepticus: a multicenter comparison. Epilepsia. 2015;56(8):1275–85.

Shangguan Y, Liao H, Wang X. Clonazepam in the treatment of status epilepticus. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15(7):733–40.

Zeiler FA et al. Magnesium sulfate for non-eclamptic status epilepticus. Seizure. 2015;32:100–8.

Zeiler FA et al. Modern inhalational anesthetics for refractory status epilepticus. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;42(2):106–15.

Sivakumar S et al. Clobazam: an effective add-on therapy in refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(6):e83–9.

Shekh-Ahmad T et al. The potential of sec-butylpropylacetamide (SPD) and valnoctamide and their individual stereoisomers in status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:298–302.

Spampanato J, Dudek FE. Valnoctamide enhances phasic inhibition: a potential target mechanism for the treatment of benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2014;55(9):e94–8.

Zeiler FA et al. Therapeutic hypothermia for refractory status epilepticus. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;42(4):221–9.

Zeiler FA et al. VNS for refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2015;112:100–13.

Lhatoo SD, Alexopoulos AV. The surgical treatment of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2007;48 Suppl 8:61–5.

Alexopoulos A et al. Resective surgery to treat refractory status epilepticus in children with focal epileptogenesis. Neurology. 2005;64(3):567–70.

Bhatia S et al. Surgical treatment of refractory status epilepticus in children: clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;12(4):360–6.

Caraballo RH et al. Ketogenic diet in pediatric patients with refractory focal status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2014;108(10):1912–6.

Thakur KT et al. Ketogenic diet for adults in super-refractory status epilepticus. Neurology. 2014;82(8):665–70.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Eric H. Grover and Yara Nazzal declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Lawrence J. Hirsch has received research support from UCB, Upsher-Smith, Lundbeck, Eisai, Sunovion, and Acorda. Dr. Hirsch also has received consultation fees from Upsher-Smith, Marinus, Monteris, and Sunovion as well as speaking honoraria from Neuropace.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Epilepsy

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grover, E.H., Nazzal, Y. & Hirsch, L.J. Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus. Curr Treat Options Neurol 18, 11 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-016-0394-5

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-016-0394-5

Keywords

- Convulsive status epilepticus

- Anti-epileptic drugs

- Benzodiazepines

- First-line treatment

- Second-line treatment

- Operational definition of status epilepticus

- Mechanistic definition of generalized CSE

- Lorazepam

- Midazolam

- Valproate

- Phenytoin

- Levetiracetam

- Lacosamide

- Refractory status epilepticus

- New onset-refractory status epilepticus