Abstract

Background

Cure from chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is readily achievable with direct-acting antivirals (DAA), but little is known about optimal management after treatment. Weight gained after DAA treatment may mitigate benefits or increase risk for liver disease progression. As the single largest sample of HCV-infected individuals receiving DAA treatment in the United States, the Veterans Affairs (VA) Birth Cohort is an ideal setting to assess weight gain after DAA treatment.

Methods

We performed a prospective study of patients dispensed DAA therapy from January 2014 to June 2015. Weight change was calculated as the difference in weight from sustained virologic response (SVR) determination to 2 years later. Demographic, weight, height, prescription, laboratory, and diagnosis code data were used for covariate definitions. We used multiple logistic regression to assess the association between candidate predictors and excess weight gain (≥ 10 lbs) after 2 years.

Results

Among 11,469 patients, 78.0% of patients were already overweight or obese at treatment initiation. Overall, SVR was achieved in 97.0% of patients. After 2 years, 52.6% of patients gained weight and 19.8% gained excess weight. In those with SVR, weight gain was as high as 38.2 lbs, with the top 10% gaining ≥ 16.5 lbs. Only 1% of those with obesity at treatment initiation normalized their weight class after 2 years. Significant predictors of post-SVR weight gain were SVR achievement, lower age, high FIB-4 score, cirrhosis, and weight class at treatment initiation.

Conclusion

Weight gain is common after DAA treatment, even among those who are overweight or obese prior to treatment. Major predictors include age, baseline weight, alcohol, cirrhosis, and SVR. Everyone receiving DAAs should be counseled against weight gain with a particular emphasis among those at higher risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Now that sustained virologic response (SVR) with direct-acting antivirals (DAA) exceeds 90%, we need evidence to inform management in the post-DAA treatment setting.1,2,3 For those achieving SVR, the American Association of the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends “evaluation for modifiable risk factors for liver injury, such as … fatty liver, and diabetes mellitus,” and to “continue disease-specific management to optimize weight loss and glycemic control”.4 SVR is also thought to reduce liver-related and overall mortality and improve extrahepatic manifestations such as diabetes.5,6,7,8 However, as obesity and insulin resistance are important risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), weight gain after DAA treatment may limit or even reverse the benefits gained from SVR achievement.

There is little research describing weight change after DAA treatment, since weight loss was a common adverse effect of prior, interferon-based therapies.9,10,11 There is some evidence that weight gain may occur after DAA treatment and SVR achievement. Recently, increased skeletal muscle mass without weight gain12 and modest weight gain of 3.2 lbs13 have been reported. However, these studies were limited by small sample sizes (32 and 76 patients) and 1-year follow-up.

Further study is warranted because weight gain in patients after attaining SVR may predispose them to liver disease progression, including NAFLD, incident diabetes mellitus, and liver fibrosis progression.14 At present, NAFLD is a growing public health issue in the United States (U.S.) and has been worsening since the 1980s concurrently with the obesity epidemic.15,16,17 NAFLD is the second most common liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation and in the near future is expected to substantially increase in prevalence.18, 19 NAFLD and fibrosis progression may in turn place these patients at risk for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).20,21,22 Thus, we aimed to explore and characterize weight gain after DAA therapy and identify predictors of weight gain, using a nationwide prospective cohort of veterans treated in the U.S. Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System. We hypothesized that this patient population would gain weight after 2 years of follow-up.

METHODS

Study Database

The VA Birth Cohort is a nationwide, prospective cohort study of all U.S. veterans born in 1945–1965. This population bears a disproportionate burden of HCV disease compared with other birth years, leading to recommendation for one-time HCV screening, regardless of other risk factors.23, 24 Information was obtained from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, the central repository of nationwide patient-level data of veterans receiving care from all U.S. VA care sites. Extracted data included patient-level demographic, anthropometric, clinical, prescription, laboratory, procedure, and diagnosis data. Inpatient and outpatient diagnoses were obtained through International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th revisions (ICD-9/10) diagnosis codes. Surgical procedures were recorded by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. This data is hosted and accessed through the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI).23, 25

Study Design and Inclusion Criteria

Using prescription fill data, we identified 11,469 patients initiating DAA treatment between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2015. Those with known SVR status and weight data before and after SVR determination were included in analysis. The observation period for weight change occurred from the time of SVR determination until 2 years after (Fig. 1). SVR achievement was defined as having a negative hepatitis C polymerase chain reaction viral load at least 11 weeks after DAA treatment completion to allow for a 1-week buffer for those receiving early testing before clinic follow-up, expected at 12 weeks after DAA completion.

Body Weight, Weight Change, and Weight Class

Body weight was obtained at three time points: (1) DAA initiation using the closest measure in the prior 90 days; (2) SVR determination using the closest weight in the following 90 days; and (3) follow-up, 2 years after SVR determination. Follow-up weight was defined as (a) the closest weight within 30 days of the 2-year time point or average if two equidistant values, (b) if not available, then the closest value within 90 days, or (c) if not available, then the interpolation of the two closest weight values within 180 days. The observation time period was chosen to exclude the treatment time period to exclude the possibility of DAA-induced weight changes and before SVR determination since unknown treatment outcome was an exclusion criterion. We calculated the weight change in the time period from treatment initiation to SVR determination and found no large mean weight change (− 0.1 ± 11.7 lbs), though noted 1468 (12.8%) of patients gained ≥ 10 lbs.

Weight change was defined as the difference between weights at SVR determination and at 2-year follow-up. The primary outcome, excess weight gain, was defined as weight change ≥ 10 lbs over the 2-year observation period, chosen to be clinically practical while also beyond the degree of weight gain expected with aging (1 to 2 lbs per year).26

Weight class was defined using height and weight to calculate the body mass index (BMI), categorized using standard cutoffs (underweight < 18.5 kg/m2; normal 18.5 to < 25; overweight 25 to < 30; class 1 obesity 30 to < 35; class 2 obesity 35 to < 40; and class 3 obesity ≥ 40).27 Height was defined as the average between measures at SVR determination and at follow-up. Class 2 and 3 obesity groups were combined due to small sample sizes.

Covariates at DAA Initiation

Covariates obtained at the time of DAA initiation, chosen a priori, included age, sex, and race (White, Black, or other), DAA regimen (classified as sofosbuvir-based or non-sofosbuvir), pre-treatment viral load (log-transformed), viral genotype (1, 2, 3, or 4–6/multiple), Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) (categorized as < 1.45, 1.45–3.25, and > 3.25),28 renal glomerular filtration rate (GFR, in mL/min/1.73 m2),29 Alcohol Use Disorders Identifications Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) scores, and smoking status (current, former, or never smoker). International Classification of Diseases, 9th modification (ICD-9), diagnosis codes (with 2 outpatient codes or 1 inpatient code) were used to define cirrhosis, depression or severe mental illness (depression, major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder), diabetes, illicit drug use, and alcohol use disorder. Smoking status was defined using health factors (current, former, or never smoker).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics including graphical assessment of weight at DAA initiation, SVR determination, follow-up, and weight change were used to assess weight distributions overall and across SVR determination groups. Across these same groups, we also compared average differences in weight change. Significance of differences in proportions and continuous variables were tested with chi-square tests and t tests, respectively. Univariate and multiple logistic regression models were performed to identify important predictors of weight gain from the list of a priori covariates. We used a full-model approach, and then restricted only to patients achieving SVR and used the strongest predictors to estimate the probability of excess weight gain based on patient clinical characteristics. We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of heterogeneity, by excluding patients with extreme weight changes (< 1st and > 99th percentile) and those not achieving SVR. To account for potential bias introduced by missing data, we performed multiple imputation using 10 imputed datasets produced by fully conditional specification method on missing covariate data (range of missing data 0 to 5.4% for all variables).30 Statistical significance for all tests was defined with a two-tailed p value of < 0.05. Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained from both the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, and from Yale University School of Medicine. All data analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The analytic dataset contained 11,496 patients, with complete covariate data available in 10,596 patients (92.4% of eligible sample). It was comprised of 96.4% males, 59.9% White race, 85.2% genotype 1 infection, 37.9% with elevated FIB-4 score > 3.25, and 38.5% patients with cirrhosis by diagnosis code. SVR was achieved in 97.0% of patients. At the time of treatment initiation, 78.1% of patients were overweight or obese, including 41.3% overweight (BMI 25–29.9) and 36.8% obese (BMI 30 or higher). Those with weight gain ≥ 10 lbs were more likely to have achieved SVR (97.7% vs. 96.8%) and to have FIB-4 score > 3.25 (43.4% vs. 37.2%), cirrhosis (43.4% vs. 37.2%), and obesity class 1 (25.8% vs. 24.3%) or class 2/3 (15.1% vs. 11.4%, p < 0.05 for all), but did not differ in other comorbidities (Table 1). Those with and without SVR were similar regarding age, gender, race, DAA regimen, renal function, diabetes, alcohol use, and mental illness. However, those not achieving SVR had higher rates of genotype 2 and 3 infection (15.6% vs. 8.7% for genotype 2; 16.2% vs. 4.5% for genotype 3), FIB-4 score > 3.25 (48.4% vs. 37.6%), cirrhosis (46.4% vs. 38.3%), HCC (12.5% vs. 3.8%), and obesity at treatment initiation (44.4% vs. 35.6%), drug use (49.3% vs. 41.9%), and current smoking (65.4% vs. 57.6%, p < 0.05 for all).

Body Weight Change

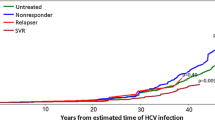

Overall, the weight change over 2 years was (mean ± standard deviation) 0.44 ± 12.9 lbs. The mean weight change was 0.56 ± 12.8 lbs in those achieving SVR and − 3.43 ± 14.6 lbs in those without SVR (p < 0.0001). Over the 2-year observation period, 6027 (52.6%) patients gained weight; this was more common in those achieving SVR compared with no SVR (52.9% vs. 40.9%, p < 0.0001). Overall, 2275 patients (19.8%) gained ≥ 10 lbs; again, more common in those achieving SVR compared with those not achieving SVR (21.5% vs. 16.2%, p = 0.01). On graphical assessment and assessment of weight change percentiles (Fig. 2), those achieving SVR had more weight gain or less weight loss across all percentiles of weight change. With SVR, the weight gain was as high as 38.2 lbs for those in the top percentile, with 10% of patients gaining at least 16.5 lbs.

In those with normal BMI at treatment initiation, 22% became overweight during follow-up (Fig. 3). Among those who were obese at treatment initiation, very few patients (1%) normalized their BMI at 2 years, but many patients progressed to higher BMI classes. Of those overweight, 16% became obese. Of those with class 1 obesity, 14% progressed to class 2/3 obesity.

Multivariable Models for Excess Weight Gain

In the all-inclusive multiple logistic regression model (Table 2), factors associated with excess weight gain included SVR achievement (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.14, 2.10), FIB-4 score > 3.25 (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.06, 1.44), and cirrhosis (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.08, 1.34). Additionally, we observed a dose-effect relationship with BMI class at DAA treatment initiation: overweight, obesity class 1, and obesity class 2/3 were associated with significant and increasing odds of excess weight gain (OR 1.17, 1.25, and 1.50, respectively). Factors associated with lower odds of excess weight gain included older age ≥ 65 years (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.57, 0.85) and no alcohol use compared with moderate use (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.69, 0.94).

Sensitivity Analyses

A missing covariate data was present in 873 (7.6%) of the 11,469 study-eligible patients. Analyses using multiple imputation models (Supplemental Table 1), and excluding patients with extreme weight changes (n = 229) (not shown) or without SVR achievement (n = 322) (not shown), revealed the same predictors of excess weight gain observed in the primary model. In the assessment of the clinical characteristics of those with missing data (Supplemental Table 2), there were notably more excluded White patients, as well as fewer with cirrhosis, diabetes, substance use, or mental health disorders.

Probability Estimates for Weight Gain

The four most influential variables were age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), cirrhosis (diagnosis code or FIB-4 > 3.25), BMI class at treatment initiation (combining under- and normal weight), and alcohol use (combining hazardous use and alcohol use disorder). To aid in clinical decision-making and better illustrate their impact, we estimated probability of weight gain > 10 lbs employing only these variables in a logistic regression. The estimated probability of excess weight gain ranged from 12.7 to 34.1%, with the highest probability observed in younger patients, with cirrhosis, class 2/3 obesity, and moderate alcohol use; and the lowest probability in under/normal weight, older patients, without cirrhosis, and no alcohol use (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative, prospective study of 11,469 veterans treated for HCV with DAA, we found that despite 78.1% of patients already being overweight or obese at treatment initiation, over half of patients gained weight and nearly 20% gained ≥ 10 lbs after 2 years. The highest risk for excess weight gain was observed younger patients with cirrhosis, obesity, and moderate alcohol consumption. Dependent on important clinical characteristics (age, presence of cirrhosis, weight at treatment initiation, and alcohol use habits), patients can expect from 1 in 5 to a 1 in 3 chance of excess weight gain after 2 years. Over the observation period of this study, most patients gained weight; only a small minority decreased or normalized weight.

Several mechanisms may explain weight gain after SVR, including removal of chronic inflammation or infectious burden, increased nutritional intake, and improved hepatic anabolic function. Chronic systemic infection or inflammation are processes which may lead to metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia.31, 32 These processes may lead to excess metabolic burden, suppressing weight gain that might otherwise have occurred. In this setting, SVR achievement might result in weight gain in the absence of lifestyle changes to promote weight loss. This may also explain our finding of failed SVR associated with weight loss, which may be due to ongoing chronic infection, metabolic burden, and progressive hepatic fibrosis with cirrhosis.

Increased energy intake may be another explanation for weight gain after SVR. HCV is known to lead to reduced quality of life, depression, and fatigue,33, 34 all of which may lead to reduced intake and resultant weight loss. Additionally, advanced liver disease is associated with protein-calorie malnutrition and sarcopenia, which might also lead to weight loss.35 HCV cure may result in improvement in well-being or changes in hunger-inducing hormones, which can result in increased nutritional intake and therefore weight gain.

Reduced hepatic anabolic function in advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis has been associated with a reduced skeletal muscle mass.36, 37 HCV without cirrhosis has also been associated with reduced muscle mass.38, 39 Thus, HCV cure may improve liver synthetic function and increase skeletal muscle mass production. In this study, we found that both advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis are associated with excess weight gain after DAA treatment, which may correlate with improved hepatic synthetic function from SVR.

However, with age, decreases in skeletal muscle and bone mass have been observed, with concurrent increases in fat mass.40 This may suggest that the observed weight gain in this middle-aged population might be from fat accumulation. Our finding of older age associated with lower odds of weight gain may also be explained by age-related reduction in skeletal and muscle mass. Future studies are needed to better characterize the metabolic risk associated with weight gain in this population.

Most importantly, weight gain in a cohort with 78.1% baseline prevalence of overweight or obesity raises concern for increased risk of obesity-related disease. It is concerning that 16% of overweight patients became obese at 2 years, and 14% of class 1 obesity patients at baseline progressed to class 2 or 3 obesity at 2 years. Further, fewer than 1% of patients with obesity at baseline normalized weight during the 2 years of observation. We found an increased odds of excess weight gain in those with the highest baseline weight. This is concerning as those already at risk for obesity complications are at higher risk for excess weight gain. All patients in this study are already middle-aged at the time of DAA initiation. Thus, it is possible that the long-engrained lifestyle habits which led some to higher weights by the time of treatment initiation could contribute to even more weight gain after DAA treatment.

Although we defined a 10-lb weight gain as clinically important in this study, smaller magnitudes of weight gain can still pose health risks. For example, for those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, every 5 pounds gained has been associated with a 14% increased risk of incident diabetes in just the first year after antiretroviral therapy initiation.41 Conversely, a modest weight loss of 5% body weight is known to improve insulin resistance, blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and risk of cardiovascular or NAFLD-related steatohepatitis.42,43,44 Thus, although a 10-lb threshold is important, any weight gain may be associated with harm.

The AASLD recommends counseling on weight gain avoidance in all who achieve SVR.4 However, it is currently unclear who stands to benefit most from these measures, or whether counseling is sufficient to prevent weight gain. Our findings suggest that DAA treatment is an opportune time to discuss post-SVR management and to frame the importance of weight in long-term metabolic risk and associated liver and non-liver outcomes. Although prevention of weight gain can be advised as currently recommended, it should be considered a minimum measure, and active weight loss is necessary for most patients who already are overweight or obese.

Another recommendation based on our results is stricter alcohol reduction or even abstinence. We found that moderate alcohol use predicted a higher odds of weight gain. Alcohol is both an appetite stimulant and a carbohydrate load, resulting in positive energy balance when consumed in moderate quantities.45 However, with excess use, it is also known to cause multiple complications including protein-calorie and micronutrient malnutrition, sarcopenia, and chronic liver disease.46 In this sample, those with moderate alcohol use likely consume enough to obtain positive energy balance without suffering other complications leading to weight loss. Thus, those achieving SVR may be at risk for excess weight with moderate alcohol use (in addition to any potential direct liver injury from alcohol) and may benefit from alcohol abstinence to prevent further weight gain.

The economic burden of end-stage liver disease is immense, with direct costs estimated to be $2.5 billion and indirect costs as much as $10.6 billion.47 Prevention of liver disease progression through treatment of excess weight and prevention of weight gain holds potential to reduce healthcare burden, decrease extrahepatic complications of HCV, and increase quality of life in patients after DAA treatment.14 Beyond liver disease, the healthcare costs associated with obesity are immense, estimated to be $150 billion per year in the U.S..48 This underscores the importance of identifying weight gain in this population since worsening obesity would be expected to reduce any healthcare cost-savings obtained through successful HCV cure.

Finally, we developed a simplified model of predictors of post-SVR weight gain to estimate the predicted probabilities of excess weight gain. Although the majority of patients have a high probability of gaining weight, with these results (Table 3), clinicians may identify those at the highest risk for excess weight gain at the time of DAA initiation. For example, a 55-year-old patient with moderate alcohol use who has cirrhosis and class 2 obesity at treatment initiation would be expected on average to have a 34.1% probability (95% CI 29.9%, 38.4%) of gaining at least 10 lbs in 2 years. The use of a risk stratification tool may allow clinicians to identify patients for whom focused counseling, interventions, and resources for weight loss can be prioritized. Using a probability-based tool may allow policymakers and clinicians to establish benchmarking criteria to systematically identify and assess patients for obesity risk factors after completion of HCV treatment, though further research is needed to identify predictors and to consolidate those factors in to a simple and effective tool.

This study aimed to describe weight change in this sample of patients, rather than make comparisons with alternative groups. The rationale for this approach is due to concern for validity of such comparisons. Comparing with those with chronic HCV not receiving DAA therapies, there is a concern for confounding by factors leading to decision not to treat, such as comorbid substance abuse, decompensated cirrhosis, or other coinfections. Comparing those achieving SVR with non-SVR, other factors may be confounding such as drug adherence, prior undiagnosed cirrhosis, and comorbidity. In consideration of comparison with an uninfected veteran sample, we observe an obesity prevalence of 37.7% in our sample, in contrast to 41% in the general veteran population, suggesting our sample is distinct.15, 49 Additionally, our rationale for defining excess weight gain as > 10 lbs in 2 years is that it is distinct from age-related weight gain, which occurs at a rate of 1 to 2 lbs per year.50, 51

Our study benefits from several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the largest known analysis to date to assess post-SVR weight gain with the longest period of follow-up. Our findings are also strengthened by the utilization of a large, nationally derived, individual-level, longitudinal database with directly measured weights, prescription, and laboratory data. Additionally, the persistence of regression modeling findings in sensitivity analyses and after covariate adjustment strengthens the validity of our results. These findings of weight gain after SVR are not alternatively due to DAA medication effect as weight change was defined by a period starting approximately 3 months after treatment was already completed.

However, our study has several limitations. We were unable to differentiate the type of weight gain observed (skeletal, muscular, or adipose tissue), which would be possible with bioelectrical impedance or imaging-based tests. Further, a two-year observation period may be too short to observe a significant loss of non-fat mass, and this study did not include body composition data. The 2-year follow-up duration is the longest follow-up period for a study investigating weight gain after SVR, but weight changes may follow a different trajectory after 2 years. Longer follow-up will be particularly relevant given increasing HCV disease burden affecting younger patients undergoing treatment earlier in life.52 It will also provide the opportunity to measure the impact post-SVR weight gain has on the incidence of comorbidities such as diabetes, HCC, and NAFLD. The difference observed in those achieving SVR compared with those without SVR suggests that HCV cure modifies the natural history of weight gain. However, patients not achieving SVR are likely to be clinically different from those with SVR in other ways besides body weight, which limits comparability between these groups and forms our basis for not using a comparison group. We emphasize that this study is primarily investigating weight change after SVR attainment and factors associated with excess weight gain. While we did not exclude patients failing to achieve SVR, we also found no difference in sensitivity analysis excluding this subgroup. To enhance the argument for or against causality in future studies, utilization of advanced analytic methods such as propensity score matching or interrupted time series design can be considered. Finally, this sample of primarily male veterans may limit the generalizability of these findings to the U.S. population, and studies including women and non-veteran civilians are warranted.

Confirmatory studies of these predictors of weight gain and investigation of other potential factors would better allow identification of those at high risk for weight gain and of new predictors of weight gain after SVR. This could allow us to focus healthcare resources on those who would stand to benefit the most. Linking weight gain to liver and metabolic diseases such as NAFLD, cirrhosis, HCC, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases would facilitate development of clinical prediction tools these diseases. Further study of special populations will be important, such as those receiving liver transplantation, for whom weight gain and graft steatosis have been reported.53, 54 Also, further elucidation of mechanisms resulting in weight gain after HCV cure may inform specific targets for intervention.

CONCLUSION

We report weight gain in a large proportion of patients after DAA treatment in a large, nationwide, cohort of 11,469 U.S. veterans with chronic HCV infection. In this prospective sample, we observed that 78% were overweight or obese at the time of DAA initiation, and over 20% of patients achieving SVR gained excess weight of at least 10 lbs over 2 years. Weight gain was more commonly observed with younger age, baseline overweight or obesity, cirrhosis, and moderate alcohol use. Future studies are needed to clarify the long-term implications and both liver and non-liver outcomes associated with weight gain in the post-SVR context, as well as the role of clinical interventions to prevent weight gain after DAA treatment.

Change history

06 October 2020

JGIM published the article matched with the editorial in this issue in the July 2020 issue. Our apologies to the authors of the paper and the editorial.

Abbreviations

- AASLD:

-

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AUDIT-C:

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDW:

-

Corporate data warehouse

- HCV:

-

Chronic hepatitis C virus

- DAA:

-

Direct-acting antiviral

- FIB-4:

-

Fibrosis-4

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- SVR:

-

Sustained virologic response

- U.S. :

-

United States

- VA:

-

Veterans Affairs

References

Asselah T, Boyer N, Saadoun D, Martinot-Peignoux M, Marcellin P. Direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: optimizing current IFN-free treatment and future perspectives. Liver Int 2016;36 Suppl 1:47–57.

Ampuero J, Romero-Gomez M. Hepatitis C Virus: Current and Evolving Treatments for Genotypes 2 and 3. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2015;44:845–857.

Alqahtani S, Sulkowski M. Current and Evolving Treatments of Genotype 1 Hepatitis C Virus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2015;44:825–843.

Jacobson IM, Lim JK, Fried MW. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Practice Update-Expert Review: Care of Patients Who Have Achieved a Sustained Virologic Response After Antiviral Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1578–1587.

El-Serag HB, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Kramer J. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virological response in Veterans with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2016;64:130–137.

Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Mole LA. Impact of Sustained Virologic Response with Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment on Mortality in Patients with Advanced Liver Disease. Hepatology 2017.

Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Mole LA. Direct-Acting Antiviral Sustained Virologic Response: Impact on Mortality in Patients without Advanced Liver Disease. Hepatology 2018.

Cacoub P, Desbois AC, Comarmond C, Saadoun D. Impact of sustained virological response on the extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C: a meta-analysis. Gut 2018:gutjnl-2018-316234.

Conjeevaram HS, Wahed AS, Afdhal N, Howell CD, Everhart JE, Hoofnagle JH, Virahep CSG. Changes in insulin sensitivity and body weight during and after peginterferon and ribavirin therapy for hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2011;140:469–477.

Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2444–2451.

Fioravante M, Alegre SM, Marin DM, Lorena SL, Pereira TS, Soares EC. Weight loss and resting energy expenditure in patients with chronic hepatitis C before and during standard treatment. Nutrition 2012;28:630–634.

Sugimoto R, Iwasa M, Hara N, Tamai Y, Yoshikawa K, Ogura S, Tanaka H, et al. Changes in liver function and body composition by direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol Res 2017.

Schlevogt B, Deterding K, Port K, Siederdissen CHZ, Sollik L, Kirschner J, Mix C, et al. Interferon-free cure of chronic Hepatitis C is associated with weight gain during long-term follow-up. Z Gastroenterol 2017;55:848–856.

Malnick SD, Knobler H. The medical complications of obesity. Journal of the Association of Physicians 2006;99:565–579.

Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016;315:2284–2291.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:766–781.

Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73–84.

Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, Perumpail RB, Harrison SA, Younossi ZM, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;148:547–555.

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, Srishord M. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:524–530 e521; quiz e560.

El-serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004;126:460–468.

Younossi ZM, Otgonsuren M, Henry L, Venkatesan C, Mishra A, Erario M, Hunt S. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States from 2004 to 2009. Hepatology 2015;62:1723–1730.

Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TAR, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010;51:1972–1978.

Sarkar S, Esserman DA, Skanderson M, Levin FL, Justice AC, Lim JK. Disparities in hepatitis C testing in U.S. veterans born 1945-1965. J Hepatol 2016;65:259–265.

Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Ward JW. Hepatitis C virus testing of persons born during 1945-1965: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:817–822.

Backus LI, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, Yip GH, Mole LA. Hepatitis C virus screening and prevalence among US veterans in Department of Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1549–1552.

Dutton GR, Kim Y, Jacobs Jr DR, Li X, Loria CM, Reis JP, Carnethon M, et al. 25-year weight gain in a racially balanced sample of US adults: The CARDIA study. Obesity 2016;24:1962–1968.

Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J Chronic Dis 1972;25:329–343.

Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, Sulkowski MS, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2006;43:1317–1325.

Stevens PE, Levin A, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group M. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:825–830.

Lee KJ, Carlin JB. Multiple imputation for missing data: fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. American journal of epidemiology 2010;171:624–632.

Nishitsuji H, Funami K, Shimizu Y, Ujino S, Sugiyama K, Seya T, Takaku H, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection induces inflammatory cytokines and chemokines mediated by the cross talk between hepatocytes and stellate cells. J Virol 2013;87:8169–8178.

Zampino R, Marrone A, Restivo L, Guerrera B, Sellitto A, Rinaldi L, Romano C, et al. Chronic HCV infection and inflammation: Clinical impact on hepatic and extra-hepatic manifestations. World J Hepatol 2013;5:528–540.

Foster G, Goldin R, Thomas H. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection causes a significant reduction in quality of life in the absence of cirrhosis. Hepatology 1998;27:209–212.

Cacoub P, Comarmond C, Domont F, Savey L, Desbois AC, Saadoun D. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2016;3:3–14.

Periyalwar P, Dasarathy S. Malnutrition in cirrhosis: contribution and consequences of sarcopenia on metabolic and clinical responses. Clinics in liver disease 2012;16:95–131.

Hanai T, Shiraki M, Nishimura K, Ohnishi S, Imai K, Suetsugu A, Takai K, et al. Sarcopenia impairs prognosis of patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutrition 2015;31:193–199.

Dasarathy S, Merli M. Sarcopenia from mechanism to diagnosis and treatment in liver disease. J Hepatol 2016;65:1232–1244.

Gowda C, Brown TT, Compher C, Forde KA, Kostman J, Shaw PA, Tien PC. Prevalence and predictors of low muscle mass in HIV/viral hepatitis coinfection. AIDS (London, England) 2016;30:2519.

Gowda C, Compher C, Amorosa VK, Lo Re III V. Association between chronic hepatitis C virus infection and low muscle mass in US adults. Journal of viral hepatitis 2014;21:938–943.

St-Onge MP, Gallagher D. Body composition changes with aging: the cause or the result of alterations in metabolic rate and macronutrient oxidation? Nutrition 2010;26:152–155.

Herrin M, Tate JP, Akgun KM, Butt AA, Crothers K, Freiberg MS, Gibert CL, et al. Weight Gain and Incident Diabetes Among HIV-Infected Veterans Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy Compared With Uninfected Individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;73:228–236.

Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, Safford M, Knowler WC, Bertoni AG, Hill JO, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care 2011:DC_102415.

Blackburn G. Effect of degree of weight loss on health benefits. Obesity research 1995;3:211s–216s.

Goldstein DJ. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 1992;16:397–415.

Caton S, Ball M, Ahern A, Hetherington M. Dose-dependent effects of alcohol on appetite and food intake. Physiology & behavior 2004;81:51–58.

Lieber CS. Relationships between nutrition, alcohol use, and liver disease. Alcohol Research and Health 2003;27:220–231.

Neff GW, Duncan CW, Schiff ER. The current economic burden of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology & hepatology 2011;7:661.

Kim DD, Basu A. Estimating the medical care costs of obesity in the United States: systematic review, meta-analysis, and empirical analysis. Value in Health 2016;19:602–613.

Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, Washington DL, Lee J, Haskell S, Uchendu US, et al. The Obesity Epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: Prevalence Among Key Populations of Women and Men Veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:11–17.

Williams PT, Wood PD. The effects of changing exercise levels on weight and age-related weight gain. International journal of obesity 2006;30:543.

Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiologic reviews 2009;31:7–20.

Suryaprasad AG, White JZ, Xu F, Eichler BA, Hamilton J, Patel A, Hamdounia SB, et al. Emerging epidemic of hepatitis C virus infections among young nonurban persons who inject drugs in the United States, 2006-2012. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:1411–1419.

Richards J, Gunson B, Johnson J, Neuberger J. Weight gain and obesity after liver transplantation. Transplant international 2005;18:461–466.

Seo S, Maganti K, Khehra M, Ramsamooj R, Tsodikov A, Bowlus C, McVicar J, et al. De novo nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation 2007;13:844–847.

Funding

NIH T32 DK007017-41

VA-ORD Office of Rural Health

NIH NIAAA U01 AA026224

NIH NCATS – UL1 TR001863

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained from both the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, and from Yale University School of Medicine.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 75 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Do, A., Esserman, D.A., Krishnan, S. et al. Excess Weight Gain After Cure of Hepatitis C Infection with Direct-Acting Antivirals. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2025–2034 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05782-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05782-6