Abstract

Background

Robust evidence is lacking on optimal timing of statin administration and its impact on patient outcomes.

Objective

This study aims to evaluate among incident statin users the relationship between those prescribed evening vs. daily dosing instructions, medication adherence, and changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c).

Design

This is an observational cohort study at Sutter Health, a community-based healthcare system, 2010–2016.

Participants

Patients were ≥ 35 years of age as of the first statin prescription (baseline), with 12 to 36 months of electronic health record activity before and after baseline. Incident use was defined as no statin prescription in 12 months prior to baseline.

Main Measures

Differences in medication adherence (proportion of days covered ≥ 0.80) over 12 months from baseline and mean change in LDL-c between 12 and 24 months from baseline were measured using regression modeling, adjusting for baseline demographics and clinical, prescriber, and statin characteristics.

Key Results

Among 31,252 patients with valid statin prescriptions between 2010 and 2016, 5099 eligible incident statin users (mean age, 63 years) were identified, of whom 53% were prescribed evening and 47% daily dosing instructions. No difference in likelihood of statin adherence over 12 months was observed for evening vs. daily dosing (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.90; 95% CI 0.75, 1.08). No differences were observed in mean change in LDL-c (adjusted mean difference 1.42 mg/dL; 95% CI − 1.02, 3.89) or likelihood of attaining LDL-c < 70 mg/dL (adjusted OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.67, 1.04) for evening vs. daily dosing over a mean of 19 months follow-up.

Conclusions

Among incident statin users from a real-world clinical setting, those with daily and evening dosing instructions had similar adherence rates and mean changes in LDL-c. Given potential clinical equipoise for evening and daily dosing, clinicians should consider patient-tailored statin dosing instructions to reduce potentially unnecessary regimen complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Statins are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States (U.S.), with > 25% of U.S. adults > 40 years of age taking a statin.1, 2 Some statins (i.e., fluvastatin, lovastatin, and simvastatin) have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labels recommending evening administration, given their short half-lives and the occurrence of peak cholesterol biosynthesis in the early morning.3, 4 Conversely, other statins (i.e., atorvastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, and rosuvastatin), given their longer half-lives, have U.S. FDA labels recommending daily administration, without mention of time of day.5 These dosing strategies are based on the chronobiology of cholesterol synthesis with the goal of ensuring therapeutic plasma concentrations of the statin during peak cholesterol biosynthesis (i.e., between midnight and 3 a.m.).4

The evidence for greater low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) lowering with evening dosing for certain statins is derived from limited studies. Awad et al. synthesized evidence on the effects of morning vs. evening statin dosing on cholesterol fractions.6 The review included 11 studies (10 clinical trials and 1 observational study), from 4 to 12 weeks in duration and ranging from 12 to 299 participants (1034 participants in total).6 The authors concluded from this review that statins with short half-lives should be taken in the evening due to more pronounced lowering of LDL-c and total cholesterol compared to morning dosing and that statins with long half-lives can be taken at any time of the day,6 consistent with current U.S. FDA labeling. However, given the short durations and small sample sizes of the studies included in this review, robust evidence is lacking on optimal timing of statin administration in clinical practice.4, 7,8,9,10,11

While statins have been commercially available in the U.S. for more than three decades,1 little epidemiologic research is available on how clinicians prescribe these drugs to patients with regard to daily vs. evening dosing instructions. Moreover, it is unclear how such instructions impact medication adherence, which in turn affects LDL-c lowering. Evening dosing of a statin may introduce unnecessary regimen complexity and lead to poorer adherence if a patient takes concomitant medications at other times of the day, such as in the morning or with certain meals.12 Alternatively, evening statin dosing may serve as a reminder for patients if it coincides with their evening routine.12

In this observational cohort study, we used an EHR research database from a large, community-based healthcare delivery system between 2010 and 2016 to evaluate among incident statin users the relationship between those prescribed daily vs. evening statin dosing and (1) medication adherence over 12 months and (2) changes in LDL-c between 12 and 24 months follow-up.

METHODS

Setting and Data Sources

This study was conducted at Sutter Health, a large community-based healthcare delivery system in northern California. Annually, Sutter Health provides medical services to approximately three million patients across 130 primary care and specialty ambulatory clinics. The Sutter Health Institutional Review Board approved this research study.

Study Participants and Eligibility Criteria

We identified managed-care beneficiaries in the EHR with a statin prescription between 2010 and 2016. We required patients to be at least 35 years of age on the date of the first statin monotherapy prescription during the study period (index date), have activity (i.e., documented encounter, medical claim, or medication order) in the EHR 12 to 36 months prior to and after the index date, and have at least one pharmacy claim for the prescribed statin on or up to 12 months after the index date. We conservatively chose age 35 based on the USPSTF’s recommendation for low- to moderate-dose statin therapy in adults ages 40–75 years meeting indication criteria.13 We further required patients to have an LDL-c measurement on or within 12 months prior to the index date (baseline measurement) and 12 to 24 months after the index date (follow-up measurement). We excluded patients who were not incident statin users, evidenced by a statin prescription in the 12 months prior to the index date. We further excluded patients who received a statin prescription during a hospital visit or one that was sent to a mail-order pharmacy; those with changes to statin prescription intensity, according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) classification of low-, moderate-, and high-intensity statins14; those who had changes to statin dosing instructions (e.g., first prescription with daily dosing instructions and a subsequent prescription with evening dosing instructions) during follow-up; or those with unconventional dosing instructions (e.g., every other day).

Assessment of Statin Dosing Instructions

Among eligible cohort patients, we classified statin dosing instructions as either daily or evening based on the ‘Sig’ field in the medication order in the EHR. A pharmacist (Z.A.M.) manually reviewed the instruction field for each prescription and categorized accordingly.

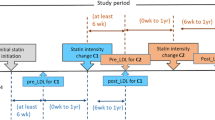

Outcome Measures

The main outcomes for this study were medication adherence and changes in LDL-c. Medication adherence was measured as proportion of days covered (PDC), expressed as the total days’ supply of statin prescriptions based on pharmacy claims over a 12-month observation window (Fig. 1).15 We used a standard cut-point of PDC ≥ 0.80 to define adherence.16 Changes in LDL-c were measured from baseline to follow-up. Baseline LDL-c was defined as the value recorded in the EHR on the index date or closest to that date within the prior 12 months. Follow-up LDL-c was defined as the value recorded in the EHR closest to 12 months, but no more than 24 months, after the index date. We categorized patients as achieving LDL-c target when their follow-up LDL-c measurement was < 70 mg/dL, based on ACC/AHA guidelines.14

Covariates

Data were extracted from the EHR on patient demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity) and clinical characteristics (body mass index [BMI], blood pressure, comorbidities) recorded in the 12 months prior to the index date. We calculated a Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score for each patient as a measure of overall disease burden.17 We used 2010 Census tract-level data to capture the median household income. We categorized patients as having an established primary care provider (PCP). We further categorized the prescriber of the index statin as the patient’s own PCP, other PCP, or a specialist. Lastly, we categorized statin prescriptions as low, moderate, or high intensity based on their daily dosing.14

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We used descriptive statistics to summarize baseline patient demographics and clinical characteristics, as well as characteristics of the prescriber and statin. Means, standard deviations (SD), medians, and interquartile ranges were calculated for continuous variables. Percentages were calculated for categorical variables.

Primary Analysis

We used logistic regression models to examine differences in odds of medication adherence (PDC ≥ 0.80) and attainment of an LDL-c target of < 70 mg/dL and linear regression models to examine differences in mean change in LDL-c from baseline to follow-up, each, by the main predictor variable of statin dosing instructions (evening vs. daily). For all outcomes, we ran simple and multivariable regression models. Multivariable regression models, at minimum, included patient, prescriber, and prescription covariates shown in Table 1 and a covariate for whether the statin was a long or short half-life drug. For linear and dichotomous LDL-c outcomes, we ran additional multivariable regression models that included covariates for (1) time between baseline and follow-up LDL-c and (2) PDC (measured from the index date to the date of the follow-up LDL-c value).

Secondary Analysis

For secondary analyses, to isolate the effects of specific dosing instructions from the effects attributable to individual statins, we repeated primary analyses among a subset of patients prescribed atorvastatin and simvastatin, the most commonly prescribed statins with FDA labels for daily and evening dosing, respectively. For all analyses, a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All tests were two-tailed.

RESULTS

Description of Study Cohort

We identified 31,252 managed-care beneficiaries with a statin prescription between 2010 and 2016; 5099 met full study eligibility criteria (Online Appendix Fig. 1). Patients had a mean age of 63 years, 49% were female, and 61% were non-Hispanic white (Table 1). A majority of patients received the index statin prescription from their own PCP (77%), followed by an endocrinologist (11%). Fifty-three percent of patients (N = 2718) were prescribed a statin with evening dosing instructions, and 47% (N = 2381) were prescribed a statin with daily dosing instructions. Patients with evening vs. daily dosing instructions were similar with respect to most baseline demographics and clinical characteristics.

Among those with evening dosing instructions, approximately 84% received a statin with an FDA label recommending evening dosing (Online Appendix Table 1); the most commonly prescribed statin with evening dosing instructions was simvastatin (72% of all prescriptions with evening dosing instructions). Among those with daily dosing instructions, 93% received a statin with an FDA label recommending daily dosing; the most commonly prescribed statin with daily dosing instructions was atorvastatin (70% of all prescriptions with daily dosing instructions).

Primary Analysis

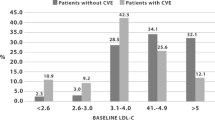

Overall, mean PDC for incident statin users was 0.69, with 52% of patients classified as adherent (PDC ≥ 0.80) (Table 2). After statistical adjustment, no difference in likelihood of statin adherence was observed for evening vs. daily dosing instructions over an average of 577 days (approximately 19 months) of follow-up (adjusted model 1 OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.75, 1.08; Table 3). Similarly, after statistical adjustment, differences between evening and daily dosing were mitigated for odds of attaining LDL-c target (adjusted model 3 OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.67, 1.04) and mean changes in LDL-c (adjusted model 3 difference 1.42 mg/dL; 95% CI − 1.02, 3.87). Estimated adjusted mean changes in LDL-c are shown in Figure 2 for all statin users by daily and evening dosing instructions. The average time from statin initiation to LDL-c follow-up was 508 days (range 365–731 days).

Adjusted mean change in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) from baseline by statin dosing instructions. Estimates with 95% confidence intervals for all patients (“Overall”) receiving a statin, and for those receiving simvastatin or atorvastatin, derived from adjusted logistic regression models.

Secondary Analysis

Patients prescribed simvastatin with instructions for evening vs. daily dosing were, on average, younger (61 vs. 68 years), less frequently had atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD; 15 vs. 27%), and had higher mean baseline LDL-c (131 vs. 90 mg/dL) (Online Appendix Table 2). Those prescribed atorvastatin for evening vs. daily dosing were on average older (68 vs. 62 years), more frequently had ASCVD (38% vs. 20%), and had lower mean baseline LDL-c (112 vs. 134 mg/dL).

On unadjusted analysis, mean PDC was lower for patients prescribed simvastatin with evening vs. daily dosing instructions (0.69 vs. 0.81; P < 0.001), with a smaller percentage of patients classified as adherent (51 vs. 69%; P < 0.001) (Online Appendix Table 3). Patients prescribed simvastatin for evening dosing (consistent with FDA label) had a higher baseline LDL-c, larger change in LDL-c at follow-up, and a smaller percentage attaining an LDL-c < 70 mg/dL compared to daily dosing. Mean PDC was similar for patients prescribed atorvastatin prescribed with evening vs. daily dosing instructions (0.71 vs. 0.70; P = 0.26). Patients prescribed atorvastatin for evening dosing (inconsistent with FDA label) had a lower baseline LDL-c, smaller change in LDL-c on follow-up, and a larger percentage attaining an LDL-c < 70 mg/dL compared to daily dosing.

After statistical adjustment, no difference in likelihood of statin adherence was observed when comparing simvastatin prescribed with evening vs. daily dosing instructions (adjusted model 1 OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.49, 1.15; Table 4) or atorvastatin prescribed with evening vs. daily dosing instructions (adjusted model 1 OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.72, 1.24; Table 4). Similarly, no differences were observed in the likelihood of attaining an LDL-c target < 70 mg/dL or mean changes in LDL-c for evening vs. daily dosing among those treated with simvastatin (adjusted model 4 OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.54, 1.38; adjusted model 3 mean difference − 0.37 mg/dL; 95% CI − 5.42, 4.69; Table 4) or atorvastatin (adjusted model 3 OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.69, 1.30; adjusted model 4 mean difference − 1.72 mg/dL; 95% CI − 5.65, 2.21; Table 4). Estimated adjusted mean changes in LDL-c are shown in Figure 2 for daily and evening dosing instructions, among those with prescriptions for simvastatin and atorvastatin, separately.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of adult managed-care beneficiaries from a large healthcare delivery system initiating statin therapy, we found no differences in statin medication adherence over a 12-month period or changes in LDL-c over a mean of 19 months for those prescribed daily vs. evening dosing instructions, after accounting for a number of potential confounders. The primary results were consistent with those from secondary analyses among patients prescribed atorvastatin or simvastatin, the two most commonly prescribed statins in our sample with U.S. FDA labels for daily and evening dosing, respectively. Overall, adherence during the first 12 months after initiating a new statin was suboptimal, with approximately half of patients classified as nonadherent.

Findings from our study have important clinical implications. It is often taught that certain statins (e.g., simvastatin), based on shorter half-lives, should be prescribed for evening or bedtime administration.9 This recommendation is based on U.S. FDA labels, which are largely supported by pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics studies.7, 10, 18, 19 These studies are limited by small sample sizes of relatively healthy volunteers with short durations of follow-up and are, thus, not reflective of real-world clinical practice. Consequently, evidence is lacking on optimal statin administration timing as it relates to medication adherence and changes in LDL-c, despite the fact that one in four Americans > 40 years of age takes a statin.2 Specific timing instructions for statins may introduce unnecessary complexity into a patient’s medication regimen, potentially leading to nonadherence and in turn poorer LDL-c lowering.6 However, we found no associations between timing of statin dosing instructions and adherence to statins or LDL-c outcomes, suggesting that clinicians should consider patient-tailored dosing instructions when prescribing statins.12

Our findings are consistent with a study conducted by Walter et al., which was a subanalysis of a clinical trial among 68 patients prescribed statins and whose medication adherence was measured via an electronic monitoring system.12 The authors of this analysis found that less variability in the time of day that a patient takes their statin, rather than the specific time of the day itself, was associated with improved LDL-c lowering.12 While we were unable to measure statin intake variability, both our study and theirs support personalized medication dosing schedules for patients taking statins. Future research should explore flexible ‘Sig’ creation tools in EHRs to allow for personalized dosing instructions.20

The optimal timing of statin administration is currently being evaluated in a randomized clinical trial (RCT).21 The investigators of this study seek to examine the efficacy of morning vs. evening rosuvastatin–ezetimibe administration on LDL-c lowering for up to 12 weeks.21 While a RCT is the gold standard for clinical efficacy, this study may have limited generalizability to clinical practice for addressing the question of optimal statin dosing instructions. For example, the study drug is provided free of charge and rosuvastatin–ezitimibe, only one of several statin products, is not the most commonly prescribed.1 In the absence of robust evidence from RCTs with long-term follow-up that directly addresses this issue, observational studies using rigorous methods and conducted in practice-based settings are paramount for examining optimal timing of statin administration.

Overall, patients were poorly adherent to statin therapy, with only half of patients taking at least 80% of their medication regimen during the first 12 months of therapy. This is consistent with a large body of literature on medication adherence, in general, and statins, specifically.22,23,24,25,26,27 The systematic review by Awad et al. found only three studies that assessed adherence for morning vs. evening statin dosing, each of which were small RCTs, with 24 to 132 participants; yet adherence in RCTs does not reflect how patients take medications in real-world clinical practice.9, 28, 29 Two of these studies found no significant difference in adherence between morning vs. evening statin dosing9, 28; one study reported that the adherence rate to lovastatin was higher when it was taken in the morning vs. evening.29 Our study is the first to investigate the impact of daily vs. evening dosing on medication adherence in a real-world cohort. While our study did not find differences in medication adherence for daily vs. evening dosing instructions at the population level, it is possible that dosing instructions for individual patients could make a salient difference in simplifying their medication regimens, especially if the statin dosing instructions add unnecessary complexity. Polypharmacy is common in patients taking statins for hyperlipidemia and/or primary or secondary prevention of ASCVD, as these individuals often have other risk factors requiring medication management.30

Our study has several limitations. First, although we adjusted for multiple covariates associated with statin prescribing, adherence, and changes in LDL-c, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding given the observational design of this research. Although our comparison groups were strikingly similar at baseline, unmeasured confounding remains a potential source of bias. For example, we were unable to measure lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise that might be associated with LDL-c. As such, causal inferences are restricted. Of note, we conducted sensitivity analyses on primary and secondary analyses adjusting for co-payment amount (per 30-day supply of statins), and the results were unchanged (data not shown). Second, patients may not have actually taken the statin at the time of day prescribed, potentially leading to misclassification bias. However, it is unlikely that the rate of misclassification was differential for those prescribed daily and evening dosing instructions. Third, we did not assess overall medication regimen complexity, nor did we assess how the timing of statin administration interacts with such complexity. For example, someone already taking a chronic medication (e.g., antihypertensive) in the evening might have higher adherence than someone for whom the evening statin introduces a new dosing time. Future studies are needed on this important topic. Fourth, we used pharmacy claims as a proxy for medication adherence. Thus, it was possible to measure only medication supply via PDC and not the actual consumption of statins. Nevertheless, PDC is a well-accepted method for measuring medication adherence in observational research and has been shown to be associated with health outcomes.31

Despite these limitations, this is the largest study to date examining statin administration timing. In addition, we used a practice-based cohort of real-world patients prescribed a variety of statins. Furthermore, while our cohort included managed-care beneficiaries, the study setting is a mixed-payer health system without standardized care plans or a fixed-drug formulary, allowing for natural variation in clinical practice that would be observed in most other healthcare systems in the U.S. Taken together, findings from our study have enhanced generalizability. Finally, our follow up for LDL-c outcomes of more than 19 months, on average, is significantly longer than prior studies.6

In conclusion, among incident statin users from a real-world clinical setting, those with evening vs. daily dosing instructions had similar medication adherence rates and changes in LDL-c. Adherence rates to statin regimens were poor, regardless of dosing instructions. Given potential clinical equipoise for evening and daily dosing, clinicians should consider more patient-tailored statin dosing instructions to reduce potentially unnecessary regimen complexity.

References

Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:56–65.

Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, Kit BK. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(177):1–8.

Parker TS, McNamara DJ, Brown C, et al. Mevalonic acid in human plasma: relationship of concentration and circadian rhythm to cholesterol synthesis rates in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:3037–41.

Plakogiannis R, Cohen H. Optimal low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering—morning versus evening statin administration. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:106–10.

Plakogiannis R, Cohen H, Taft D. Effects of morning versus evening administration of atorvastatin in patients with hyperlipidemia. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:2491–4.

Awad K, Serban MC, Penson P, et al. Effects of morning vs evening statin administration on lipid profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11:972–85.

Cilla DD Jr, Gibson DM, Whitfield LP, Sedman AJ. Pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin after administration to normocholesterolemic subjects in the morning and evening. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:604–9.

Saito Y, Yoshida S, Nakaya N, Hata Y, Goto Y. Comparison between morning and evening doses of simvastatin in hyperlipidemic subjects: a double-blind comparative study. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:816–26.

Wallace A, Chinn D, Rubin G. Taking simvastatin in the morning compared with evening: randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2003;327:788.

Martin PD, Mitchell PD, Schneck DW. Pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of a new HMG-CoA-reductase inhibitor, rosuvastatin, after morning or evening administration in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:472–7.

Insull W, Black D, Dujovne C, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily vs twice-daily dosing with fluvastatin, a synthetic reductase inhibitor, in primary hypercholesterolemia. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2449–55.

Walter P, Arnet I, Romanens M, Tsakiris DA, Hersberger KE. Pattern of timing adherence could guide recommendations for personalized intake schedules. J Pers Med. 2012;2:267–76.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:1997–2007.

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;129:S1-S45.

Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105–16.

Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, Sian S, Smith DB. Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:728–40.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9 and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9.

Zocor (simvastatin) [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Coro.; 2010.

Lipitor (atorvastatin) [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc.; 2009.

Yang Y, Ward-Charlerie S,Dhavie AA, Rupp MT, Green J. Quality and variability of patient directions in electronic prescriptions in the ambulatory care setting. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:691–9.

Obońska K, Kasprzak M, Sikora J, et al. The impact of the time of drug administration on the effectiveness of combined treatment of hypercholesterolemia with Rosuvastatin and Ezetimibe (RosEze): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:316.

Go AS, Fan D, Sung SH, et al. Contemporary rates and correlates of statin use and adherence in nondiabetic adults with cardiovascular risk factors: the KP CHAMP study. Am Heart J. 2017;194:25–38.

Stirratt MJ, Curtis JR, Danila MI, Hansen R, Miller MJ, Gakumo CA. Advancing the science and practice of medication adherence. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:216–22.

Ofori-Asenso R, Jakhu A, Curtis AJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the factors associated with nonadherence and discontinuation of statins among people aged ≥65 years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:798–805.

Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:526–34.

Yusuf S. Why do people not take life-saving medications? The case of statins. Lancet. 2016;388:943–5.

Grundy SM. Statin discontinuation and intolerance: the challenge of lifelong therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:562–3.

Kim SH, Kim MK, Seo HS, et al. Efficacy and safety of morning versus evening dose of controlled-release simvastatin tablets in patients with hyperlipidemia: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase III trial. Clin Ther. 2013;35:1350–60.

Kruse W, Nikolaus T, Rampmaier J, Weber E, Schlierf G. Actual versus prescribing timing of lovastatin doses assessed by electronic compliance monitoring. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1993; 45:211–5.

Guglielmi V, Bellia A, Pecchioli S, et al. Effectiveness of adherence to lipid lowering therapy on LDL-cholesterol in patients with very high cardiovascular risk: a real-world evidence study in primary care. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:36–41.

Franklin JM, Krumme AA, Tong AY, et al. Association between trajectories of statin adherence and subsequent cardiovascular events. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:1105–13.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Funding

ZAM was supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality grant (K12HS022982).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The Sutter Health Institutional Review Board approved this research study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior presentation: This work was presented, in part, at the 34th Annual International Congress for Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Risk Management; Prague, Czech Republic. August 22–26, 2018.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 49 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marcum, Z.A., Huang, HC. & Romanelli, R.J. Statin Dosing Instructions, Medication Adherence, and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol: a Cohort Study of Incident Statin Users. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 2559–2566 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05180-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05180-7