Abstract

COVID-19 is a new type of trauma that has never been conceptually or empirically analyzed in our discipline. This study aimed to investigate the impact of COVID-19 as traumatic stress on mental health after controlling for individuals’ previous stressors and traumas. We utilized a sample of (N = 1374) adults from seven Arab countries. We used an anonymous online questionnaire that included measures for COVID-19 traumatic stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and cumulative stressors and traumas. We conducted hierarchical multiple regression, with posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety as dependent variables. In the first step, in each analysis, we entered the country, gender, age, religion, education, and income as independent variables (Kira, Traumatology 7(2):73–86, 2001; Kira, Torture, 14:38–44, 2004; Kira, Traumatology, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000305). In the second step, we entered cumulative stressors and traumas as an independent variable. In the third step, we entered either COVID-19 traumatic stressors or one of its subtypes (fears of infection, economic, and lockdown) as an independent variable. Finally, we conducted structural equation modeling with PTSD, depression, and anxiety as predictors of the latent variable mental health and COVID-19 as the independent variable. Results indicated that COVID-19 traumatic stressors, and each of its three subtypes, were unique predictors of PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Thus, COVID-19 is a new type of traumatic stress that has serious mental health effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

The rapid global spread of COVID-19 has wide-ranging effects on mental health, especially for those with a pre-existing mental disorder (Campion et al., 2020). Measuring the mental health effects of COVID-19 as traumatic stress and untangling its impact from the impact of previous stressors and traumas (and the potential pre-existing conditions) on the individual is a challenge in studying the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of the individual.

COVID-19 pandemic is a new type of trauma that has never been conceptually or empirically analyzed in our discipline. Pandemics and epidemics have a broad spectrum of neuropsychiatric, economic, and mortal impacts (e.g., Watts, 1999), usually followed by critical social or historical changes. However, the construct and mental health impact of previous pandemics in history (e.g., Spanish flu of 1918, the Black Death plague 1334–1400, and the Athenian plague of 430 B.C., for history see, e.g., Huremović, 2019 ) have never been empirically examined. The eruption and unfolding of the COVID-19 pandemic is a chance to advance our understanding of pandemics as traumatic stress and try to fill this gap in trauma research and study pandemics’ effects on mental health. One of the factors that make the COVID-19 threats and this trauma type unique and even more severe than other trauma types is its uncontrolled invisibility. We can identify and actively fight or control the perpetrator through the law and other means in numerous other trauma types. However, fighting and mitigating the (COVID 19) virus (unlike other viruses and most epidemics that have well-known treatments and vaccines) depends on the further advance of scientific knowledge (e.g., developing effective vaccines and treatments) and the diligence of policy and decision-making, effective planning, and accepting and dealing with its real risks.

Another factor that makes COVID-19 a unique trauma type is that it is a continuous ongoing traumatic stress. It would most accurately be characterized as a type III trauma (ongoing), which has a greater likelihood of being experienced as more severe (e.g., Kira, 2021; Kira et al., 2008; Kira, Ashby, et al., 2013a). COVID-19-related stress is ongoing and has no clear end beyond effective and widely available and injected vaccines. Most conceptualizations of traumatic stress are based on the assumption that traumatic experiences occurred in the past. They fail to recognize continuous traumatic stress that is ongoing and may continue through the future (Eagle & Kaminer, 2013; Kira, Ashby, et al., 2013a). However, research suggests that when a traumatic experience is ongoing, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms become more significant and severe (e.g., Goral et al., 2017). Compared to types I and II traumas (Terr, 1991), type III trauma (the continuous ongoing trauma) is the most severe (Kira, 2021). Type I trauma is a single blow, for example, the death of a loved one, while type II is a series of severe stressors that continued and ended, for example, sexual abuse. Type III, the most severe, is the continuous/ongoing traumatic stress that can present itself in different subtypes and trajectories. One of these subtypes is the ongoing various discriminations subtype (e.g., Kira et al., 2015; Klonoff et al., 1999). Other subtypes may include community and intergroup violence. COVID-19 multilayered traumatic stress presents another subtype of this continuous cumulative traumatic stress (CTS) type III trauma model (e.g., Kira, Alpay, et al., 2021a; Kira, Shuwiekh, Alhuwailah, et al., 2020b; Kira, Shuwiekh, Rice, et al., 2020a). The distinction between CTS and current posttraumatic disorder (PTSD) criterion “A” that focuses on past traumas is essential (criterion “A” is either type I or type II trauma, which is less severe) to understand the effects of COVID-19. CTS and related chronic stress can cause an imbalance of neural circuitry subserving cognition, decision-making, anxiety, and mood and contribute to the pathophysiology and allostatic load (e.g., McEwen, 2017)

Furthermore, continuous traumatic stress (CTS) requires prolonged open-ended attempts to cope with chronic stressors, which may drain the person’s coping capabilities. Enduring distress would be too demanding when it persists to be further subjected endlessly to the threat, amplifying one’s vulnerabilities (Lahav, 2020). In contrast, the stressor condition in PTSD criterion “A” typically happened in the past.

COVID-19 traumatic stress is not necessarily related to the actual infection of COVID-19 but also is more related to the perceived/actual threat of the uncontrolled virus and the direct and indirect economic and social consequences of actions taken by different agencies to deal with the virus on the person and secondary trauma of the death of loved ones due to the infection by the virus. Holman and her group’s intensive work on time perspective and adversity found that ongoing stress is associated with temporal disintegration, leading to a higher past perspective associated with negative wellbeing (Holman, 2015; Holman et al., 2016; Holman & Silver, 1998). However, in COVID-19, the stress is more focused on the present or the future time perspective of potential mortal infection, and the potential temporal disintegration may have different dynamics. In COVID-19 traumatic stress, the person may have a real fear and anticipation of contracting the virus. The present and future dimensions of the stressor are evident, not the past stressors, which are the focus of current traumatic stress research. These negative anticipatory and expectancy feelings are states of awareness of physiological and neurocognitive changes in the form of adapting to future adverse events. Biological psychology research has consistently found a link between time perspective and multisystemic chronic stress. For instance, maladaptive time perspectives are associated with allostatic load and cortisol dynamics (Bourdon et al., 2020; Olivera-Figueroa et al., 2015). There is also evidence that the insula, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and the amygdala, the three brain regions involved in future anticipatory feelings (Stefanova et al., 2020), are implicated in mental health disorders such as PTSD (e.g., Liberzon et al., 2003). A growing body of research (e.g., Rönnlund et al., 2018) has found that future negative time perspectives to be the strongest predictor of perceived distress.

The fourth factor that makes COVID-19 a unique traumatic stressor is the fact that it is a multiple complex trauma. COVID-19 traumatic stress consists of various components (Kira, Shuwiekh, Rice, et al., 2020a): threat/fear of the present and future infection and death (e.g., Ornell et al., 2020; Porcelli, 2020), the actual economic hardship (e.g., McKibbin & Fernando, 2020), and the stressors and traumatic stressors related to lockdown and related isolation, disturbed life routines, and family and social life (Brooks et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020). Another critical component is the grief that is not limited only to grieving lost loved ones to COVID-19 infection, but also the loss of future hopes and expectations due to the COVID-19 eruption. The effects of epidemics such as SARS, MERS, and Ebola, which are lesser in scope and time scale and more controllable than pandemics, found to have severe neuropsychiatric effects and are associated with PTSD, depression, and anxiety (see for review and meta-analysis, Rogers et al., 2020). The impact of one of the COVID-19 stressor types or their cumulative impact can have severe mental health and cognitive sequels (For meta-analyses of the mental health impact of lockdown stressors, see, e.g., Brooks et al., 2020, Di Blasi et al., 2021; for the impact on loss of life and related prolonged grief, see, e.g., Eisma et al., 2020; Eisma et al., 2021; Lee & Neimeyer, 2020; Mayland et al., 2020; and for meta-analyses of the impact of the pandemic-related economic stressors on mental health and socioeconomic hierarchies, e.g., Bedoya et al., 2020; Farmer et al., 2020; Kira et al., 2020a, b, c, Shuwiekh et al., 2020). It also included the effects of COVID-19 fear of infection (e.g., Şimşir et al., 2021); and the adverse effects of CIVID-19 on cognition and executive functions (working memory and inhibition deficits) (see Kira et al., 2021a, b; Rogers et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on PTSD, depression, and anxiety are now well-documented (e.g., Covid et al., 2020; Ettman et al., 2020a; Ettman et al., 2020b; Holman et al., 2020a, b) (for meta-analyses, see Bueno-Notivol et al., 2020; Cooke et al., 2020; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020 & Xiong et al., 2020). However, most of these studies were limited by the lack of valid COVID-19 cumulative traumatic stress measures and did not control for the experience of previous stressors and traumas.

Prior exposure to various traumas can be a risk factor for different psychiatric disorders. Prior psychiatric disorders were found to increase COVID-19 infection and mortality (Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). However, a recent longitudinal study found, contrary to the hypothesis, that persons with pre-existing mental health conditions did not report a worsening of symptoms after exposure to the virus (Pinkham et al., 2020). As a result, this study aims to measure the impact of COVID-19 as traumatic stress on mental health after controlling for previous stressors and traumas. There are individual differences in exposure to COVID-19 stressors. Individuals can be exposed and negatively affected by COVID-19 stressor types or get exposed to all of the COVID-19 stressor types. It is essential to measure the impact of each type as well as their cumulative impact.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1

COVID-19 cumulative traumatic stressors’ scale will account for a significant level of unique variance on PTSD, depression, and anxiety, over and above previous cumulative stressors and traumas. It has direct independent significant adverse effects on mental health.

Hypothesis 2

COVID-19 traumatic stress threat/fear of infection/death subscale will account for a significant level of unique variance on PTSD, depression, and anxiety, over and above previous cumulative stressors and traumas.

Hypothesis 3

COVID-19 economic trauma subscale will account for a significant level of unique variance on PTSD, depression, and anxiety, over and above previous cumulative stressors and traumas.

Hypothesis 4

COVID-19 isolation and disturbed routine (lockdown-related stressors) subscale will account for a significant level of unique variance on PTSD, depression, and anxiety, over and above previous cumulative stressors.

Methods

Participants

One thousand and three hundred seventy-four (N = 1374) adult participants were recruited from seven Arab countries (Egypt, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Algeria, Iraq, and Palestine). We recruited the sample from different Arab countries representing the continuum of population density and socioeconomic status (SES) (e.g., Egypt for high density and low SES) to relatively low-density population and affluent socioeconomic status (e.g., Saudi Arabia for low density and high SES). It has also been recruited to represent different traumatization levels. For example, Palestinians and Iraqis have higher levels of traumatization, while Kuwaitis have much lower traumatization levels. Because the number of participants from Iraq (N = 67) and Palestine (N = 72) was relatively low, and the data indicated that they are comparable considering their trauma profile and load; also, they live under comparable situations of struggles, we pooled the participants from the two countries (N = 139). The number of Arab countries in the sample represents high variances in trauma and socioeconomic status; however, females and highly-educated people were overrepresented (For detailed differences between the countries in the sample, see Shuwiekh et al., 2020). Table 1 describes the sample.

Procedure

The initial English version of the COVID-19 traumatic stress scale questionnaire was developed by a team of three core researchers from the Center of Stress Trauma and Resiliency, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, and an Affiliate from the Center for Cumulative Trauma Studies, Stone Mountain, GA. Items were drawn from several sources and standardized to a 5-point Likert scale. The Arabic version of the questionnaire was translated and back-translated and culturally adapted by a team from the Fayoum University, Egypt. The team used Google Drive and developed a survey link. The collaborating professionals in different Arab countries followed the chain recruiting method in collecting data from their respective countries. They emailed the survey link to their contacts and asked them to email the survey link to his/her friends and relatives and other contacts after completing the survey to participate and subsequently send it on to their friends and relatives/contacts with the same request. Once the participant completed the survey, it was sent anonymously to Gmail and then downloaded to an Excel file. All questionnaires were administered individually to participants from 4/28/2020 to 5/25/2020. Participation was voluntary; each person took about 25 min to fill the questionnaire. The Fayoum University IRB approved the research as a cross-cultural study of the COVID-19 mental health impact.

Measures

COVID-19 Traumatic Stress Scale (Kira et al., 2020a, b, c; Kira, Shuwiekh, et al., 2021b)

COVID-19 traumatic stress scale is a 12-item scale including three subscales “threat/fear of the present and future infection and death” (5 items), “traumatic economic stress” (4 items), and “isolation and disturbed routines” (3 items). Items are scored on a 5-point scale, with (1) indicating not at all and (5) very much. Examples of items include “How concerned are you that you will be infected with the coronavirus?” “The Coronavirus (COVID-19) has impacted me negatively from a financial point of view.” “Over the past two weeks, I have felt socially isolated as a result of the coronavirus.” In the initial study (Kira, Shuwiekh, et al., 2021b; Kira, Shuwiekh, Rice, et al., 2020a), the scale showed good construct convergent-divergent and predictive validity. The COVID-19 scale had an alpha of .88 in the current study and, with.84, .75, and .70, for its three subscales respectively.

Cumulative Stressors and Trauma Scale (CTS-S-36 Items) (Kira et al., 2008)

The CTS-S-36 scale is designed to measure seven types of stressors/traumas (collective identity trauma, personal identity trauma, identity/achievement trauma, survival trauma, attachment trauma, secondary trauma, and gender discrimination). Additionally, the scale includes three items that measure chronic and significant life stressors. Example items for the collective identity traumas (e.g., discrimination and oppression) include “I have been discriminated against because of my sexual preference.” A personal identity trauma (e.g., early childhood traumas such as child neglect and abuse) example is “I was led to have sexual contact with a person who was older than me (when I was young.)” (Kira et al., 2014a, b). An example of a status identity/achievement trauma (e.g., failed business, fired, and drop out of school; non-criterion A traumas) is “I have been fired, terminated, laid off suddenly, or have had a failed business.” A survival trauma (e.g., combat experience, car accidents, and natural disasters) example item is “I have experienced a life-threatening medical condition (e.g., cancer, stroke, serious chronic illness, major injury, etc.).” As indicated above, the scale also includes items related to attachment trauma (e.g., abandonment by parents), secondary trauma (i.e., indirect trauma impact on others), and gender discrimination by parents and society. The CST-S evaluates cumulative stressors and traumas by measuring their occurrence, frequency, type, and negative and positive appraisals, and chronological age at the first event. However, in the present study, we used only measures of trauma occurrence (whether a trauma had occurred for a participant) and frequency, measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = never; 5 = many times).

The CST-S has shown adequate internal consistency (α = .85), and test-retest stability (.95 in 4 weeks), and predictive, convergent, and divergent validity in several different studies (e.g., Bedoya et al., 2020; Eltan, 2019; Head et al., 2012; Kira et al., 2018; Kira et al., 2019a, b; Kira et al., 2020a, b, c; Kira, Fawzi, & Fawzi, 2013b; Robles et al., 2009). The measure has been translated and validated into several languages, including Arabic, Polish, Spanish, Turkish, Korean, Burmese, and Yoruba. In the present analysis, we used the cumulative stressors and trauma occurrence subscale. The current alpha of cumulative stressors, as measured by trauma occurrence, was .89.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-V) (Blevins et al., 2015)

PCL-V is a 20-item self-report measure. Example of items “In the past month, how much were you bothered by: 1 Repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience?” Each item is scored on a five-point scale with “0” indicating “not at all” and 4 indicating “extremely.” Initial research suggests that a PCL-5 cutoff score between 31 and 33 is indicative of PTSD. A provisional PTSD diagnosis can be made by treating each item rated as 2 = “moderately” or higher as a symptom endorsed, then following the DSM-5 diagnostic rule which requires at least 1 B item (questions 1–5), 1 C item (questions 6–7), 2 D items (questions 8–14), and 2 E items (questions 15–20). The Arabic version of PCL-V has been validated in Arabic samples (Ibrahim et al., 2018). Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in the study was .94.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006)

GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that assesses general anxiety. An example of the items is “ Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? 1. Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge.” Items are scored on a 4-point scale with (0) indicating “does not exist,” and (3) indicating “nearly every day.” The scores range between 0 and 21, with a cutoff point of 15, indicating severe GAD. The GAD-7 has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82%. Increasing scores on the scale have been strongly associated with multiple domains of functional impairment (Spitzer et al., 2006). The Arabic version of GAD-7 was validated in Arabic samples (Sawaya et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale in the study was .92.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001)

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that objectifies the degree of depression severity. An example of the items is “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? a. Little interest or pleasure in doing things.” Items are scored on a 4-point scale with (0) indicating “does not exist,” and (3) indicating “nearly every day.” The scores range between 0 and 27, with a cutoff range of 15–19 indicating moderately severe depression and 20 and above indicating severe depression. The Arabic version of PhQ-9 was validated in Arabic samples (Sawaya et al., 2016). Its Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was .88.

Data Analysis

We used Cohen’s (1992, p.158) criteria and recommendations to confirm the sample size necessary to detect a medium population effect size at power = .80 for α = .05 for the study’s number of variables. The data were analyzed utilizing IBM-SPSS 22. There were no missing data reported. We conducted initial descriptive analyses and a series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses with PTSD, depression, and anxiety as dependent variables; in the first step in each analysis, we entered the country of origin, gender, age, religion, education, and income as independent variables. In the second step, we entered “cumulative stressors and traumas” as an independent variable to control for the impact of previous stressors and traumas (and potentially for the pre-existing conditions). In the third step, we entered either COVID-19 traumatic stress or one of its subscales (fears of present or future infection, economic impact, disruption routine, and isolation) as an independent variable. The data were assessed to ensure that the multivariate tests’ assumptions were fulfilled (multicollinearity, homogeneity of covariance-variance matrices, homogeneity of variances, and linearity). We tested for collinearity, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) was less than 5.00 for all variables, suggesting no multicollinearity (e.g., Hair et al., 2017). We recoded the categorical variables in demographics into dummy variables.

Furthermore, while PTSD, depression, and anxiety are different concepts and separate syndromes, they are related to a general psychopathology factor (e.g., Lahey et al., 2017). For this reason, we used structural equation modeling to test two models, one of which COVID-19 traumatic stress as an independent variable affects cumulative stressors and traumas and the latent variable of mental health (PTSD, depression, and anxiety). In the second model, the independent variables were COVID-19 fears, COVID-19 economic and COVID-19 isolation, and social trauma. We report direct, indirect, and total effects as standardized regression coefficients. We used Byrne’s (2012) recommendations for the acceptable fit criteria. The criteria for good model fit were a non-significant chi square (χ2), chi square/degrees of freedom (χ2/d.f. >5), comparative fit index (CFI) values > 0.90, and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) values < 0.08. We used a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 bootstrap samples to examine the significance of direct, indirect (mediated effects), and total effects and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (95% CI) for each trauma.

Results

General Descriptives

Only three participants in the study reported that they had contracted COVID-19 and recovered. For cumulative stressors and trauma, the mean of occurrences was 6.94 with an SD of 5.62. For COVID-19 traumatic stress, the mean was 33.52 with an SD of 8.45. For PTSD (M = 25.54, SD = 16.70), 36.6% scored at 31 or above which is the cutoff score for probable PTSD diagnosis. For the generalized anxiety disorder scale (M = 5.94, SD = 5.19), 6.3% scored at 15 or above, which is the cutoff score of severe generalized anxiety disorder. For depression (M = 7.91, SD = 6.06), 12.1% scored at or above 15, which is the cutoff score for moderate depression, while 4.9% scored at or above 20, which is the cutoff score for severe depression.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression

Results of the analysis investigating the effects of the COVID-19 traumatic stress scale on PTSD after entering previous cumulative stressors and trauma occurrences indicated that the model accounted for (R2 = .25) of the variance. While age and income were negative predictors of PTSD, CST was the strongest predictor (Beta = .34). However, COVID-19 traumatic stress added significant variance to the model, above and beyond the impact of previous cumulative stressors and traumas) (Beta = .22). Table 2 and Table 1-S (in the Supplementary information) detail these results.

Similar to results found for the overall COVID-19 scale, the results of the analysis investigating the effect of the COVID-19 threat/fear of the present and future infection/death subscale on PTSD, after entering previous cumulative stressors and traumas occurrences, indicating a model accounting for (R2 = .24) of the variance. While age and income were negative predictors of PTSD, CST was the strongest predictor of PTSD (Beta = .36). Scores on the threat/fear of infection/death accounted for significant variance in the prediction of PTSD, above and beyond the impact of previous CST (Beta = .18).

Results of analyses investigating the effect of the COVID-19 economic trauma subscale on PTSD, after controlling for previous cumulative stressors and trauma occurrences, revealed a model accounting for (R2 = .23) of the variance. Similar to previous results, while age and income were negative predictors of PTSD, CST was the strongest predictor of PTSD (Beta = .34). Scores on the economic trauma subscale were a significant unique predictor of PTSD, accounting for variance above and beyond the impact of previous CST (cumulative stressors and traumas) (Beta = .16).

In the analysis investigating the effect of the COVID-19 disrupted routines and isolation subscale on PTSD, after entering previous cumulative stressors and trauma occurrences, the model accounted for (R2 = .230) of the variance. While age and income were negative predictors of PTSD, CST was the strongest predictor of PTSD (Beta = .35). However, disrupted routines and isolation subscale was a strong significant unique predictor of PTSD above and beyond the impact of previous CST (Beta = .14).

The results of analyses investigating the effects of COVID-19 traumatic stress and its three subscales on anxiety and depression showed similar results to those of PTSD. Tables 1-S, 2-S, and 3-S in the Supplementary information detail the results of COVID-19 traumatic stress and its three subscales on depression and anxiety after entering cumulative stressors and traumas. Similar to analyses investigating PTSD, COVID-19 traumatic stress (and its three subscales) accounted for unique variance in depression and anxiety after entering previous CST. In all the analyses, variance inflation factor (VIF) values indicated no collinearity presence in the data (see Tables 1-S, 2-S, and 3-S in the Supplementary information). The reversing of the steps in all analyses by entering COVID-19 traumas and cumulative stressors and traumas in the first steps before demographics did not change the results.

SEM Results

The first model has a good fit with the data (chi square = 58.349, df = 9, p = .000, CFI = .985, RMSEA = 063). COVID-19 Economic Traumas had direct effects on cumulative stressors and traumas. It had direct and indirect effects on mental health. Its indirect effect on mental health is about 20% of its total effects and was mediated by previous cumulative stressors and traumas (CST). In this model, COVID-19 economic traumas had indirect significant medium-size effects on PTSD, depression, and anxiety. COVID-19 isolation and social trauma did not have significant direct effects on CST. It had direct and indirect effects on mental health. It had indirect small but significant effects on PTSD, depression anxiety, and depression. COVID-19 fears had direct effects on mental health and indirect small but significant effects on PTSD, depression, and anxiety. COVID-19 economic trauma had the most substantial impact on mental health. Depression accounted for the highest variance in the model (R2 = .812)

The second model had adequate fit with data (chi square = 43.864, df = 4, p = .000, CFI = .986, RMSEA = 085). In the model, COVID-19 traumatic stress had direct effects on cumulative stressors and traumas (CST). It had direct and indirect effects on mental health. Its indirect effects on mental health accounted for about 13.5% of its total effects and were mediated by previous CST. COVID-19 traumatic stress had an indirect medium (to relatively high) effect size on PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Depression accounted for the highest variance in the model (R2 = .811)

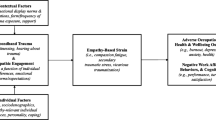

In both models, CST had a medium-size direct effect on mental health and medium-size indirect effects on PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Table 3 (and Table 4-S in the Supplementary information) provides the direct, indirect, and total effect and 95% confidence intervals for each variable in the two models. Figures 1 and 1-S in the Supplementary information provide diagrams for the direct effects of COVID-19 and its three sub-traumas on mental health.

Discussion

This the first time in history since the Spanish flu of 1918, over 100 years ago; we have an opportunity to study the mental health impact of a pandemic and explore pandemics as a different trauma type. This opportunity may allow us to learn and expand our perspective on traumatic stress and find new and innovative approaches to studying traumatic stress through a new adjusted lens beyond our current perspectives. First, the results of this study confirmed our four hypotheses. COVID-19 is a new type of traumatic stress with severe mental health effects because it is continuous and includes multiple stressors such as fears of present or future infection, economic stressors, disruption of routines, isolation and related lockdown stressors, and grieving the lost ones. Also, COVID-19 traumatic stress and its multiple components, using different analytics, were all significant predictors of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Lastly, the findings replicated previous studies on the impact of COVID-19 on mental health (for meta-analyses see, e.g., Bueno-Notivol et al., 2020; Cénat et al., 2020; Cooke et al., 2020; da Silva Junior et al., 2020; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Santabárbara et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020) (For the cumulative impact of COVID-19 stressor types, see Alpay et al., in press; Kira, Shuwiekh, Rice, et al., 2020a, Kira, Shuwiekh, et al., 2021b).

The novelty of the study is that the findings of the COVID-19 impact are over and above the impact of previous cumulative stressors and traumas and of measuring the cumulative impact of all the COVID-19 stressor types using a valid measure for COVID-19 cumulative stressors, which most previous studies did not use. The current study is the first study that controlled previous cumulative stressors and traumas. It utilized a comprehensive perspective of cumulative stressors and traumas measurement. That helped to disentangle the sheer impact of COVID-19 stressors. Previous cumulative stressors and traumas mediated a small part of their effects.

While these results seem straightforward, they have several important implications. For instance, while only three individuals in the sample (N = 1347) indicated contracting and surviving COVID-19, the anticipation, fear, and economic and social impact of COVID-19 had a significant impact on their mental health, regardless of their previous stress and trauma exposure (and potentially pre-existing conditions for those who have been impacted). However, we have to clarify that controlling for previous stressors and traumas does not necessarily mean controlling pre-existing conditions. Not all people with prior trauma exposure have a mental health problem. Most people are resilient and do not develop PTSD after experiencing a highly stressful/traumatic event.

COVID-19 and its related stressors have severe mental health consequences (PTSD, depression, and anxiety) that do not fit current trauma paradigms. Recent studies found that COVID-19 stressors do not impact only mental health; they also negatively impact executive functions (Alpay et al., in press; Kira, Alpay, et al., 2021a). One unique characteristic of COVID-19 traumatic stress is the individual’s related continuous concern about the likelihood of contracting the virus. The constant prolonged concern is further complicated by unceasing economic suffering and frequently disturbed routines and related permanent psycho-social sequelae that may include grief for losing loved ones to the virus or domestic violence. The current trauma paradigm is mainly based on the definition of trauma as termed in the criterion “A” of PTSD diagnosis of past type I or type II traumas. The experience of COVID-19 traumatic stress calls for a paradigm shift in traumatic stress research. As Horesh and Brown (2020) stated, “COVID-19 clearly shows the limitations of our current diagnostics in two ways. First, this is the time to understand the status of this crisis as a traumatic event. Second, while some types of traumas, such as war, sexual assault, and natural disasters, have been studied extensively, COVID-19 forces us to acknowledge an arguably new type of mass trauma. This crisis has highly unique characteristics, which call for a novel perspective about “what is trauma” and its implications. For one thing, it is not the only global in scope, but its impact is rippling into every aspect of society” (p. 332).

The criterion “A” definition of trauma in the DSM has been widely critiqued for not including continuous and ongoing traumas such as discrimination (e.g., Brewin et al., 2009). The results of discrimination are evident in the USA, as evidenced by the racial disparities around the experience of COVID-19. For example, African-Americans have experienced significantly higher hospitalization rates and deaths from COVID-19 (e.g., Garg, 2020). Also, the focus of recent protests against racism, white supremacy, and police brutality targeting Black Americans offer additional evidence of discrimination as traumatic stress. A recent study found that COVID-19 creates a vicious cycle, with disparities/inequalities increasing infection and death from COVID-19, and COVID-19 and its traumatic stress increasing disparities/inequalities (Kira, Shuwiekh, Alhuwailah, et al., 2020b). COVID-19 and discriminations are type III traumas, the most severe types, while criterion “A” includes either type I or II, the less severe.

An additional difficulty with the emphasis on criterion “A” on the conceptualization of trauma is the discounting of the traumatization dynamics of cumulative impact and proliferation of early stressors and traumas (Kira et al., 2018; Kira et al., 2019a, b). Discounting traumatization dynamics is particularly problematic as some research suggests that current criterion “A” trauma appears to have only 10% predictive validity concerning mental health (e.g., Kira et al., 2018; Kira et al., 2019a, b). Also, some studies have shown that most of those diagnosed with PTSD are victims of other non-criterion “A” traumas (e.g., Boals & Schuettler, 2009). The results of one recent study (Kira et al., 2019a, b) indicated that adding the non-criterion “A” stressors and traumas (such as oppression) resulted in an increased incremental predictive validity of criterion “A” over sixfold and that the non-criterion “A” stressors and traumas fully mediated the effects of criterion “A” on PTSD.

Additionally, the severe impact of COVID-19 stressors seems to translate into a post-COVID-19 syndrome beyond the current binary diagnostics that include comorbid depression, anxiety, PTSD, and executive function deficits. Studies of COVID-19 patients discovered a persistent post-COVID-19 infection syndrome that included negative neurological, neuropsychiatric, and cognitive impacts (e.g., Ayoubkhani et al., 2021; Garg et al., 2021; Nuzzo et al., 2021; Oronsky et al., 2021; Pavli et al., 2021; Wijeratne & Crewther, 2020). In addition, post-COVID-19 infection syndrome included increased suicide risk (Sher, 2021) and addiction (Håkansson, 2021). However, the evidence-based post-cumulative impact of COVID-19 prolonged stressors other than the impact of actual infection included depression, anxiety, PTSD, and cognition. This impact included minorities, social and professional groups, and the general public. Continuous complex traumas such as COVID-19 stressors rarely yield a single diagnosis but rather a profile of comorbidity syndrome. Such syndrome does not propose a new diagnostic category but describes the complex picture of the cumulative impact of continuous and prolonged COVID-19 different stressor types in some impacted individuals and groups. The concept of complex PTSD that was early suggested and recently codified in CD-11 may not be enough to describe the actual mental health impact of COVID-19 cumulative stressors.

To conclude, the current research has significant conceptual and clinical implications. Conceptually, with the COVID-19 pandemic, current frameworks of traumatic stress probably do not fit what we are experiencing in real time, and there is a need for an adjusted new lens to see the realities of type III traumas or continuous traumatic stress that have different trajectories. There is an urgent need for a comprehensive cognitive mapping of the stress and trauma field that clarifies the phenomena of stress and trauma beyond the current conceptualizations and frameworks of PTSD criterion “A.” Criterion “A” and the current PTSD is an empirically developing framework. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic is not only an individual trauma; it is also a social, national, and international trauma that will probably turn to be historical in its time scale. Clinically, there is an urgent need for innovations in prevention and intervention strategies with this new trauma type that is massive, global continuous, multilayered, and severe. The current interventions are designed for types 1 and II traumas and may not be effective with victims of type III traumas. They may need to be augmented by new and innovative interventions. Recent research provided empirical evidence of the potential effectiveness of pre-cognitive interventions and motivational work such as “will to exist-live and survive” to cope with COVID-19 traumatic stress (Kira et al., paper submitted). Both cognitive and pre-cognitive methods are vital in behavior change. Type III continuous trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral interventions need to be more developed (see Kira et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2013).

While this study’s results offer clear initial evidence for the impact of COVID-19 in the prediction of mental health, controlling for other traumas and stressors, the study has several limitations. First, the study is limited by using a convenience sample that is relatively skewed towards younger ages and females with limited and biased representation. Additionally, sampling distribution varies widely by country. This biased representation can affect the interpretation of the results as females who had higher representation in the sample usually have higher symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD than males (e.g., Valentine et al., 2019). Furthermore, the study used a cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to explore causal effects that longitudinal studies can offer. We recommend more studies that use more representative samples and longitudinal studies if feasible. Another limitation is that the measures we used are based on participants’ self-reports, which could be subject to under- or over-reporting of events due to current symptoms, embarrassment, shame, or social desirability.

Furthermore, the samples in the current study represented only Arab cultures. The results of the study need to be validated and replicated in future studies. Another limitation is that while the COVID-19 measure included the three main dimensions of the psychological impact of COVID-19, it did not include grief. Grief is not limited only to grieving lost loved ones — but also to the loss of future hopes and expectations due to the COVID-19 eruption. Future development of this scale is needed. However, despite these limitations, the study offered initial evidence for the effects of COVID-19 and the expansion of trauma’s conceptualization beyond traditional criterion “A” restrictions.

DataAvailability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alpay, E., Kira, I., Shuwiekh, H., Ashby, J. S., Turkeli, A., & Alhuwailah, A. (in press). The effects of COVID-19 continuous traumatic stress on mental health: The case of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Traumatology: A International Journal.

Ayoubkhani, D., Khunti, K., Nafilyan, V., Maddox, T., Humberstone, B., Diamond, I., & Banerjee, A. (2021). Post-covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with covid-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ, 372, n693. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n693.

Bedoya, E. Y., Ruíz, S., Córdoba, A., Rendón, G. D., Ruíz, G. I., & Gómez, G. D. (2020). Traumatic events and psychopathological symptoms in university students. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 1(1), 69–79 http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12494/17619.

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059.

Boals, A., & Schuettler, D. (2009). PTSD symptoms in response to traumatic and non-traumatic events: The role of respondent perception and A2 criterion. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(4), 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.09.003.

Bourdon, O., Raymond, C., Marin, M. F., Olivera-Figueroa, L., Lupien, S. J., & Juster, R. P. (2020). A time to be chronically stressed? Maladaptive time perspectives are associated with allostatic load. Biological Psychology, 152, 107871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2020.107871.

Brewin, C. R., Lanius, R. A., Novac, A., Schnyder, U., & Galea, S. (2009). Reformulating PTSD for DSM-V: Life after criterion A. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20443.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Bueno-Notivol, J., Gracia-García, P., Olaya, B., Lasheras, I., López-Antón, R., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 21(1), 100196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.07.007.

Campion, J., Javed, A., Sartorius, N., & Marmot, M. (2020). Addressing the public mental health challenge of COVID-19. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7, 657–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30240-6.

Cénat, J. M., Blais-Rochette, C., Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Noorishad, P. G., Mukunzi, J. N., McIntee, S. E., Dalexis, R. D., Goulet, M. A., & Labelle, P. (2020). Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Racine, N., & Madigan, S. (2020). Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347.

Covid, C. D. C., Team, R., COVID, C., Team, R., COVID, C., Team, R., et al. (2020). Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19—United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(15), 477.

da Silva Junior, F. J. G., de Souza Monteiro, C. F., Costa, A. P. C., Campos, L. R. B., Miranda, P. I. G., de Souza Monteiro, T. A., et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of young people and adults: a systematic review protocol of observational studies. BMJ Open, 10(7), e039426 http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/7/e039426.

Di Blasi, M., Gullo, S., Mancinelli, E., Freda, M. F., Esposito, G., Gelo, O. C. G., et al. (2021). Psychological distress associated with the COVID-19 lockdown: A two-wave network analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 284, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.016.

Eagle, G., & Kaminer, D. (2013). Continuous traumatic stress: Expanding the lexicon of traumatic stress. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032485.

Eisma, M. C., Boelen, P. A., & Lenferink, L. I. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 288, 113031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031.

Eisma, M. C., Tamminga, A., Smid, G. E., & Boelen, P. A. (2021). Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19, natural causes and unnatural causes: An empirical comparison. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278, 54–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.049.

Eltan, S. (2019). Psychometric properties of the cumulative trauma scale: Evaluation of the reliability and validity in a Turkish sample. A thesis submitted to graduate school of social science, Middle East Technical University, Turkey.

Ettman, C. K., Abdalla, S. M., Cohen, G. H., Sampson, L., Vivier, P. M., & Galea, S. (2020a). Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2019686–e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686.

Ettman, C. K., Abdalla, S. M., Cohen, G. H., Sampson, L., Vivier, P. M., & Galea, S. (2020b). Low assets and financial stressors associated with higher depression during COVID-19 in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 75, 501–508.

Farmer, N., Wallen, G. R., Baumer, Y., & Powell-Wiley, T. M. (2020). COVID-19: Growing health disparity gaps and an opportunity for health behavior discovery? Health Equity, 4(1), 316–319. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2020.0026.

Garg, S. (2020). Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(15), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3.

Garg, P., Arora, U., Kumar, A., & Wig, N. (2021). The “post-COVID” syndrome: How deep is the damage? Journal of Medical Virology, 93(2), 673–674. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26465.

Goral, A., Lahad, M., & Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2017). Differences in posttraumatic stress characteristics by duration of exposure to trauma. Psychiatry Research, 258, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.079.

Håkansson, A. (2021). Post-COVID syndrome: Need to include risk of addiction in research and multi-disciplinary clinical work. Psychiatry Research, 301, 113961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113961.

Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. saGe publications.

Head, D., Singh, T., & Bugg, J. M. (2012). The moderating role of exercise on stress-related effects on the hippocampus and memory in later adulthood. Neuropsychology, 26(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027108.

Holman, E. A. (2015). Time perspective and social relations: A stress and coping perspective. In M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, & W. van Beek (Eds.), Time perspective theory: Review, research, and application (pp. 419–436). Springer.

Holman, E. A., & Silver, R. C. (1998). Getting “stuck” in the past: Temporal orientation and coping with trauma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1146–1163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1146.

Holman, E. A., Silver, R. C., Mogle, J. A., & Scott, S. B. (2016). Adversity, time, and well-being: A longitudinal analysis of time perspective in adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 31(6), 640–651. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000115.

Holman, E. A., Garfin, D. R., Lubens, P., & Silver, R. C. (2020a). Media exposure to collective trauma, mental health, and functioning: Does it matter what you see? Clinical Psychological Science, 8(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858300.

Holman, E. A., Thompson, R. R., Garfin, D. R., & Silver, R. C. (2020b). The unfolding COVID-19 pandemic: A probability-based, nationally representative study of mental health in the United States. Science Advances, 6(42), eabd5390. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd5390.

Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. (2020). Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 12(4), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000592.

Huremović, D. (2019). Brief history of pandemics (pandemics throughout history). In D. Huremović (Ed.), Psychiatry of pandemics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15346-5_2.

Ibrahim, H., Ertl, V., Catani, C., Ismail, A. A., & Neuner, F. (2018). The validity of posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1839-z.

Kira, I. (2001). Taxonomy of trauma and trauma assessment. Traumatology 7, no., 2(2001), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/153476560100700202.

Kira, I. (2004). Secondary trauma in treating refugee survivors of torture and their families. Torture, 14, 38–44.

Kira, I. A. (2021). Taxonomy of stressors and traumas: An update of the development-based trauma framework (DBTF): A life-Course perspective on stress and trauma. Traumatology. Online First. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000305.

Kira, I. A., Lewandowski, L., Templin, T., Ramaswamy, V., Ozkan, B., & Mohanesh, J. (2008). Measuring cumulative trauma dose, types, and profiles using a development-based taxonomy of traumas. Traumatology, 14(2), 62–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608319324.

Kira, I., Ashby, J. S., Lewandowski, L., Alawneh, A. N., Mohanesh, J., & Odenat, L. (2013a). Advances in continuous traumatic stress theory: Traumatogenic dynamics and consequences of intergroup conflict: The Palestinian adolescents case. Psychology, 4, 396–409. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.44057.

Kira, I., Fawzi, M., & Fawzi, M. (2013b). The dynamics of cumulative trauma and trauma types in adult patients with psychiatric disorders: Two cross-cultural studies. Traumatology: An International Journal, 19, 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765612459892.

Kira, I. A., Omidy, A. Z., & Ashby, J. S. (2014a). Cumulative trauma, appraisal, and coping in Palestinian and American Indian adults: Two cross-cultural studies. Traumatology: An International Journal, 20(2), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099397.

Kira, I., Lewandowski, L., Chiodo, L., & Ibrahim, A. (2014b). Advances in systemic trauma theory: Traumatogenic dynamics and consequences of backlash as a multi-systemic trauma on Iraqi refugee Muslim adolescents. Psychology, 5, 389–412 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Kira, I. A., Ashby, J. S., Omidy, A. Z., & Lewandowski, L. (2015). Current, continuous, and cumulative trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy: A new model for trauma counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 37(4), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.37.4.04.

Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H., Kucharska, J., Fawzi, M., Ashby, J. S., Omidy, A. Z., Abou-Mediene, S., & Lewandowski, L. (2018). Trauma Proliferation and Stress Generation (TPSG) dynamics and their implications for clinical science. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(5), 582–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000304.

Kira, I., Barger, B., Shuwiekh, H., Kucharska, J., & Al-Huwailah, A. H. (2019a). Cumulative stressors and traumas and suicide: A non-linear cusp dynamic systems model. Psychology, 10, 1999–2018 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Kira, I., Fawzi, M., Shuwiekh, H., Lewandowski, L., Ashby, J., & Al Ibraheem, B. (2019b). Do adding attachment, oppression, cumulative and proliferation trauma dynamics to PTSD criterion “A” improve its predictive validity: Toward a paradigm shift? Current Psychology. Advanced online first, 40, 2665–2679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00206-z.

Kira, I., Shuwiekh, H., Rice, K., Ashby, J., Elwakeel, S., Sous, M., et al. (2020a). Measuring COVID-19 as traumatic stress: Initial psychometrics and validation. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping., 26, 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1790160.

Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H. A. M., Alhuwailah, A., Ashby, J. S., Sous Fahmy Sous, M., Baali, S. B. A., et al. (2020b). The effects of COVID-19 and collective identity trauma (intersectional discrimination) on social status and well-being. Traumatology. Advance online publication., 27, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000289.

Kira, I., Barger, B., Shuwiekh, H., Kucharska, J., & Al-Huwailah, A. (2020c). The threshold non-linear model for the effects of cumulative stressors and traumas: A chained cusp catastrophe analysis. Psychology, 11, 385–403. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2020.113025.

Kira, I., Alpay, E. H., Turkeli, A., Shuwiekh, H., & Ashby, J.S.& Alhuwailah, A. (2021a). The effects of COVID-19 traumatic stress on executive functions: The case of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping. Advanced online Publication., 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1869444.

Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H., Ashby, J. S., & Rice, K.& Alhuwailah, A. (2021b). Measuring COVID-19 Stressors and their impact: The second-order factor model and its four first-order factors: infection fears, economic, grief, and lockdown stressors. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping. Online first., 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2021.1920270.

Klonoff, E. A., Landrine, H., & Ullman, J. B. (1999). Racial discrimination and psychiatric symptoms among Blacks. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 5(4), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.5.4.329.

Krishnamoorthy, Y., Nagarajan, R., Saya, G. K., & Menon, V. (2020). Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers, and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Lahav, Y. (2020). Psychological distress related to COVID-19–The contribution of continuous traumatic stress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.141.

Lahey, B. B., Krueger, R. F., Rathouz, P. J., Waldman, I. D., & Zald, D. H. (2017). A hierarchical causal taxonomy of psychopathology across the life span. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 142–186.

Lee, S. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2020). Pandemic Grief Scale: A screening tool for dysfunctional grief due to a COVID-19 loss. Death Studies. Online first., 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1853885.

Li, L., Li, F., Fortunati, F., & Krystal, J. H. (2020). Association of a prior psychiatric diagnosis with mortality among hospitalized patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection. JAMA, 3(9), e2023282–e2023282. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23282.

Liberzon, I., Britton, J. C., & Luan Phan, K. (2003). Neural correlates of traumatic recall in posttraumatic stress disorder. Stress, 6(3), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/1025389031000136242.

Mayland, C. R., Harding, A. J., Preston, N., & Payne, S. (2020). Supporting adults bereaved through COVID-19: A rapid review of the impact of previous pandemics on grief and bereavement. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(2), e33–e39.

McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic Stress, 1, 2470547017692328. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547017692328.

McKibbin, W., & Fernando, R. (2020). The economic impact of COVID-19, in Baldwin, R. & di Mauro, B. W. (Eds). Economics in the time of COVID-19, pp.45-52. CEPR Press Centre for Economic Policy Research 33 Great Sutton Street London, EC1V 0DX UK.

Murray, L. K., Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (2013). Trauma-focused al therapy for youth who experience continuous traumatic exposure. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032533.

Nuzzo, D., Cambula, G., Bacile, I., Rizzo, M., Galia, M., Mangiapane, P., Picone, P., Giacomazza, D., & Scalisi, L. (2021). Long-term brain disorders in post Covid-19 neurological syndrome (PCNS) patient. Brain Sciences, 11(4), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11040454.

Olivera-Figueroa, L. A., Juster, R. P., Morin-Major, J. K., Marin, M. F., & Lupien, S. J. (2015). A time to be stressed? Time perspectives and cortisol dynamics among healthy adults. Biological Psychology, 111, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.09.002.

Ornell, F., Schuch, J. B., Sordi, A. O., & Kessler, F. H. P. (2020). “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 42(3), 232–235. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008.

Oronsky, B., Larson, C., Hammond, T. C., Oronsky, A., Kesari, S., Lybeck, M., & Reid, T. R. (2021). A review of persistent post-COVID syndrome (PPCS). Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-021-08848-3.

Pavli, A., Theodoridou, M., & Maltezou, H. C. (2021). Post-COVID syndrome: Incidence, clinical spectrum, and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Archives of Medical Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.010.

Pinkham, A. E., Ackerman, R. A., Depp, C. A., Harvey, P. D., & Moore, R. C. (2020). A Longitudinal investigation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of individuals with pre-existing severe mental illnesses. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113493.

Porcelli, P. (2020). Fear, anxiety, and health-related consequences after the COVID-19 epidemic. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation, 17(2), 103–111.

Robles, M. E., Badosa, J. M., Roig, A., Pina, B., & Feixas Viaplana, G. (2009). La evaluación del estrés y del trauma: Presentación de la versión española de la escala de trauma acumulativo (CTS). Revista de Psicoterapia, 20(80), 89–104.

Rogers, J., Chesney, E., Oliver, D., Pollak, T., McGuire, P., Fusar-Poli, P., Zandi, M., Lewis, G., & David, A. (2020). Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. The LANCET Psychiatry. Online First., 7, 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0.

Rönnlund, M., Åström, E., Adolfsson, R., & Carelli, M. G. (2018). Perceived stress in adults aged 65 to 90: Relations to facets of time perspective and COMT val158Met polymorphism. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00378.

Santabárbara, J., Lasheras, I., Lipnicki, D. M., Bueno-Notivol, J., Pérez-Moreno, M., López-Antón, R., de la Cámara, C., Lobo, A., & Gracia-García, P. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic: An updated meta-analysis of community-based studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 109, 110207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110207.

Sawaya, H., Atoui, M., Hamadeh, A., Zeinoun, P., & Nahas, Z. (2016). Adaptation and initial validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic speaking Lebanese psychiatric outpatient sample. Psychiatry Research, 239, 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.030.

Sher, L. (2021). Post-COVID syndrome and suicide risk. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 114(2), 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcab007.

Shuwiekh, H., Kira, I., Fahmy, M., Ashby, J. S., Alhuwailah, A., Baali, S., et al. (2020). The differential mental health impact of COVID-19 in Arab countries. Current Psychology. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01148-7.

Şimşir, Z., Koç, H., Seki, T., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Death Studies, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1889097.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Lowe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Stefanova, E., Dubljević, O., Herbert, C., Fairfield, B., Schroeter, M. L., Stern, E. R., et al. (2020). Anticipatory feelings: Neural correlates and linguistic markers. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 113, 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.015.

Terr, L. C. (1991). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1034-9_18.

Usher, K., Bhullar, N., & Jackson, D. (2020). Life in the pandemic: Social isolation and mental health. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29, 2756–2757. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15290.

Valentine, S. E., Marques, L., Wang, Y., Ahles, E. M., De Silva, L. D., & Alegría, M. (2019). Gender differences in exposure to potentially traumatic events and diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by racial and ethnic group. General Hospital Psychiatry, 61, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.10.008.

Wang, Q., Xu, R., & Volkow, N. D. (2020). Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: Analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry, 20, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20806.

Watts, S. J. (1999). Epidemics and history: Disease, power, and imperialism. Yale University Press.

Wijeratne, T., & Crewther, S. (2020). Post-COVID 19 Neurological Syndrome (PCNS); A novel syndrome with challenges for the global neurology community. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 419, 117179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117179.

Wu, T., Jia, X., Shi, H., Niu, J., Yin, X., Xie, J., & Wang, X. (2020). Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117.

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L., Gill, H., Phan, L., et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001.

Zhou, H., Lu, S., Chen, J., Wei, N., Wang, D., Lyu, H., Shi, C., & Hu, S. (2020). The landscape of cognitive function in recovered COVID-19 patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 129, 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.06.022.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Gada Ouda Hijazi, the researcher at the Palestinian Planning Center, and to Jumana Daibes a faculty of Allied Medical Science, in the Arab American University, Palestine, West Bank, who helped to collect data from the West Bank of Palestine.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 144 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kira, I.A., Shuwiekh, H.A., Ashby, J.S. et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Traumatic Stressors on Mental Health: Is COVID-19 a New Trauma Type. Int J Ment Health Addiction 21, 51–70 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00577-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00577-0