Abstract

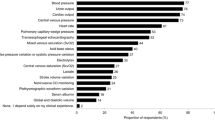

This study was to investigate and define what is considered as a current clinical practice in hemodynamic monitoring and vasoactive medication use after cardiac surgery in Italy. A 33-item questionnaire was sent to all intensive care units (ICUs) admitting patients after cardiac surgery. 71 out of 92 identified centers (77.2 %) returned a completed questionnaire. Electrocardiogram, invasive blood pressure, central venous pressure, pulse oximetry, diuresis, body temperature and blood gas analysis were identified as routinely used hemodynamic monitoring, whereas advanced monitoring was performed with pulmonary artery catheter or echocardiography. Crystalloids were the fluids of choice for volume replacement (86.8 % of Centers). To guide volume management, central venous pressure (26.7 %) and invasive blood pressure (19.7 %) were the most frequently used parameters. Dobutamine was the first choice for treatment of left heart dysfunction (40 %) and epinephrine was the first choice for right heart dysfunction (26.8 %). Half of the Centers had an internal protocol for vasoactive drugs administration. Intra-aortic balloon pump and extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation were widely available among Cardiothoracic ICUs. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were suspended in 28 % of the Centers. The survey shows what is considered as standard monitoring in Italian Cardiac ICUs. Standard, routinely used monitoring consists of ECG, SpO2, etCO2, invasive BP, CVP, diuresis, body temperature, and BGA. It also shows that there is large variability among the various Centers regarding hemodynamic monitoring of fluid therapy and inotropes administration. Further research is required to better standardize and define the indicators to improve the standards of intensive care after cardiac surgery among Italian cardiac ICUs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

St. André AC, DelRossi A. Hemodynamic management of patients in the first 24 hours after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2082–93. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000178355.96817.81.

Vincent JL, Rhodes A, Perel A, et al. Clinical review: update on hemodynamic monitoring—a consensus of 16. Crit Care. 2011;15:229–36. doi:10.1186/cc10291.

Marik PE, Monnet X, Teboul JL. Hemodynamic parameters to guide fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:1. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-1-1.

Müller M, Junger A, Bräu M, et al. Incidence and risk calculation of inotropic support in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass using an automated anaesthesia record-keeping system. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:398–404. doi:10.1093/bja/89.3.398.

Ahmed I, House CM, Nelson WB. Predictors of inotrope use in patients undergoing concomitant coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and aortic valve replacement (AVR) surgeries at separation from cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:24. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-4-24.

Overgaard CB, Dzavík V. Inotropes and vasopressors: review of physiology and clinical use in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;118:1047–56. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728840.

Gillies M, Bellomo R, Doolan L, Buxton B. Bench-to-bedside review: inotropic drug therapy after adult cardiac surgery—a systematic literature review. Crit Care. 2005;9:266–79. doi:10.1186/cc3024.

Nielsen DV, Hansen MK, Johnsen SP, Hansen M, Hindsholm K, Jakobsen CJ. Health outcomes with and without use of inotropic therapy in cardiac surgery: results of a propensity score-matched analysis. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1098–108. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000224.

Leone M, Vallet B, Teboul JL, Mateo J, Bastien O, Martin C. Survey of the use of catecholamines by French physicians. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:984–8. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2172-1.

Kastrup M, Markewitz A, Spies C, et al. Current practice of hemodynamic monitoring and vasopressor and inotropic therapy in post-operative cardiac surgery patients in Germany: results from a postal survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:347–58. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01190.x.

Carl M, Alms A, Braun J, et al. S3 guidelines for intensive care in cardiac surgery patients: hemodynamic monitoring and cardiocirculary system. Ger Med Sci. 2010;. doi:10.3205/000101.

Sponholz C, Schelenz C, Reinhart K, Schirmer U, Stehr SN. Catecholamine and volume therapy for cardiac surgery in Germany—results from a postal survey. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103996. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103996.

Kastrup M, Carl M, Spies C, Sander M, Markewitz A, Schirmer U. Clinical impact of the publication of S3 guidelines for intensive care in cardiac surgery patients in Germany: results from a postal survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:206–13. doi:10.1111/aas.12009.

Gershengorn HB, Wunsch H. Understanding changes in established practice: pulmonary artery catheter use in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2667–76. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a41e.

Vincent JL, Pinsky MR, Sprung CL, et al. The pulmonary artery catheter: in medio virtus. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3093–6. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818c10c7.

Cowie B. Does the pulmonary artery catheter still have a role in the perioperative period? Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39:345–55.

Chiang Y, Hosseinian L, Rhee A, Itagaki S, Cavallaro P, Chikwe J. Questionable benefit of the pulmonary artery catheter after cardiac surgery in high-risk patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29:76–81. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2014.07.017.

Judge O, Ji F, Fleming N, Liu H. Current use of the pulmonary artery catheter in cardiac surgery: a survey study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29:69–75. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2014.07.016.

Reeves ST, Finley AC, Skubas NJ, et al. Basic perioperative transesophageal echocardiography examination: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:543–58. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a00616.

Jacka MJ, Cohen MM, To T, Devitt JH, Byrick R. The use of and preferences for the transesophageal echocardiogram and pulmonary artery catheter among cardiovascular anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1065–71. doi:10.1097/00000539-200205000-00003.

Myburgh JA, Finfer S, Bellomo R, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch or saline for fluid resuscitation in intensive care. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1901–11. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209759.

Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 versus Ringer’s Acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:124–34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1204242.

Guidet B, Martinet O, Boulain T, et al. Assessment of hemodynamic efficacy and safety of 6 % hydroxyethylstarch 130/0.4 vs. 0.9 % NaCl fluid replacement in patients with severe sepsis: the CRYSTMAS study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R94. doi:10.1186/cc11358.

Annane D, Siami S, Jaber S, et al. Effects of fluid resuscitation with colloids vs crystalloids on mortality in critically ill patients presenting with hypovolemic shock: the CRISTAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1809–17. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280502.

Meybohm P, Van Aken H, De Gasperi A, et al. Re-evaluating currently available data and suggestions for planning randomised controlled studies regarding the use of hydroxyethyl starch in critically ill patients—a multidisciplinary statement. Crit Care. 2013;17:R166. doi:10.1186/cc12845.

Marik PE, Cavallazzi R. Does the central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? An updated meta-analysis and a plea for some common sense. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1774–81. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a25fd.

Cavallaro F, Sandroni C, Antonelli M. Functional hemodynamic monitoring and dynamic indices of fluid responsiveness. Minerva Anestesiol. 2008;74:123–35.

de Waal EE, Rex S, Kruitwagen CL, Kalkman CJ, Buhre WF. Dynamic preload indicators fail to predict fluid responsiveness in open-chest conditions. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:510–5. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181958bf7.

Lansdorp B, Lemson J, van Putten MJ, de Keijzer A, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P. Dynamic indices do not predict volume responsiveness in routine clinical practice. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:395–401. doi:10.1093/bja/aer411.

Vincent JL, Pelosi P, Pearse R, et al. Perioperative cardiovascular monitoring of high-risk patients: a consensus of 12. Crit Care. 2015;19:224. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0932-7.

Monnet X, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising: five rules, not a drop of fluid! Crit Care. 2015;19:18. doi:10.1186/s13054-014-0708-5.

Bastien O, Vallet B. French multicentre survey on the use of inotropes after cardiac surgery. Crit Care. 2005;9:241–2. doi:10.1186/cc3482.

De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:779–89. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0907118.

Mebazaa A, Pitsis AA, Rudiger A, et al. Clinical review: practical recommendations on the management of perioperative heart failure in cardiac surgery. Crit Care. 2010;14:201. doi:10.1186/cc8153.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the Centers that participated in our survey. The full list of responding Centers is available in the “Appendix”.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

On behalf of the SIAARTI Study Group on Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Centers that contributed to this survey, listed in alphabetical order of town:

-

1.

Ospedali Riuniti Umberto I-Lancisi-Salesi, Ancona

-

2.

A.O. S. G. Moscati, Avellino

-

3.

A.O.U. Policlinico Giovanni XXIII, Bari

-

4.

Anthea Hospital, Bari

-

5.

Casa di Cura S.Maria, Bari

-

6.

Ospedali Riuniti, Bergamo

-

7.

Clinica Humanitas Gavazzeni, Bergamo

-

8.

Policlinico S.Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna

-

9.

Villa Torri Hospital, Bologna

-

10.

Spedali Civili, Brescia

-

11.

Istituto Ospedaliero Fondazione Poliambulanza, Brescia

-

12.

Istituto Clinico San Rocco, Brescia

-

13.

Casa di Cura Pineta Grande, Castelvolturno

-

14.

A.O.G.Brotzu, Cagliari

-

15.

A.O.U. Vittorio Emanuele, Catania

-

16.

Policlinico Universitario Magna Graecia, Catanzaro

-

17.

A.O. S. Croce e Carle, Cuneo

-

18.

A.O.U. Careggi, Firenze

-

19.

A.O.U. S.Martino, Genova

-

20.

P. O. Vito Fazzi, Lecce

-

21.

Città di Lecce Hospital, Lecce

-

22.

P.O. Alessandro Manzoni, Lecco

-

23.

A.O. Ospedale Civile, Legnano

-

24.

A.O. Carlo Poma, Mantova

-

25.

Ospedale del Cuore G. Pasquinucci, Massa

-

26.

A.O. Ospedali RiunitiPapardo-Piemonte, Messina

-

27.

Istituto Clinico Sant’Ambrogio, Milano

-

28.

A.O. Niguarda Ca’ Granda, Milano

-

29.

Ospedale Luigi Sacco, Milano

-

30.

IRCCS Centro Cardiologico Monzino, Milano

-

31.

IRCCS Ospedale San Raffaele, Milano

-

32.

IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Milano (Rozzano)

-

33.

IRCCS Policlinico S.Donato, Milano (San Donato)

-

34.

IRCCS MultiMedica, Milano (Sesto S.Giovanni)

-

35.

Casa di Cura Hesperia Hospital, Modena

-

36.

A.O. San Gerardo, Monza

-

37.

A.O. Specialistica dei Colli, Ospedale Monaldi, Napoli

-

38.

Clinica Mediterranea, Napoli

-

39.

A.O.U. Maggiore della Carità, Novara

-

40.

Policlinico Università di Padova, Padova

-

41.

ISMETT, Palermo

-

42.

Villa Maria Eleonora Hospital, Palermo

-

43.

A.O.U. Ospedale Maggiore, Parma

-

44.

A.O. Ospedale R. Silvestrini, Perugia

-

45.

A.O.U. Pisana – Cisanello, Pisa

-

46.

A.O. S. Carlo, Potenza

-

47.

ICLAS – Istituto Clinico di Alta Specialità, Rapallo

-

48.

Villa Maria Cecilia Hospital, Ravenna (Cotignola)

-

49.

A.O. S.Filippo Neri, Roma

-

50.

A.O. S.Camillo Forlanini, Roma

-

51.

Ospedale S.Andrea, Roma

-

52.

Casa di Cura European Hospital, Roma

-

53.

Policlinico Tor Vergata, Roma

-

54.

Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli – Università Cattolica, Roma

-

55.

Policlinico Umberto I – Università Sapienza, Roma

-

56.

Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-medico, Roma

-

57.

Ospedale Civile SS. Annunziata, Sassari

-

58.

A.O.U Senese, Ospedale S. Maria alle Scotte, Siena

-

59.

Casa di Cura Villa Verde, Taranto

-

60.

Ospedale Civile G. Mazzini, Teramo

-

61.

A.O. Santa Maria, Terni

-

62.

A.O. Ospedale Mauriziano Umberto I, Torino

-

63.

A.O.U Città della Salute e della Scienza – Molinette, Torino

-

64.

Ospedale Santa Chiara, Trento

-

65.

Ospedale S.Maria dei Battuti Ca’ Foncello, Treviso

-

66.

A.O.U. Ospedali Riuniti, Trieste

-

67.

A.O.U. S.Maria della Misericordia, Udine

-

68.

Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi, Varese

-

69.

Ospedale dell’Angelo, Venezia (Mestre)

-

70.

A.O.U. Ospedale Civile Maggiore, Verona

-

71.

Ospedale San Bortolo, Vicenza

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bignami, E., Belletti, A., Moliterni, P. et al. Clinical practice in perioperative monitoring in adult cardiac surgery: is there a standard of care? Results from an national survey. J Clin Monit Comput 30, 347–365 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-015-9725-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-015-9725-4