Abstract

We sought to assess the prevalence, severity of symptoms, and risk factors of uninvestigated dyspepsia in a population-based study in Argentina. Eight hundred thirty-nine valid questionnaires were evaluated. Dyspepsia was present in 367 subjects (43.2%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 39.8–46.6); 110 (13.6%) had overlap with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The group with dyspepsia without GERD consisted of 257 subjects (29.6%; 95% CI, 26.5–32.7), 183 (71.1%) had ulcer-like dyspepsia, and 74 (28.9%) had dysmotility-like dyspepsia. Symptoms were considered very severe in 1.9%, severe in 14.0%, moderate in 59.5%, and mild in 24.5% of the subjects. Dyspepsia was associated with a score >14 on the psychosomatic symptom scale (PSC) (OR, 2.52; 95% CI, 1.75–3.61), a family history of diseases of the esophagus or stomach (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.19–2.52) and an educational level >12 years (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.05–2.29). Dyspepsia is especially prevalent in Argentina. In a significant proportion of dyspeptic subjects, the severity of symptoms interferes with daily activities. A higher PSC, positive family history, and a higher educational level are risk factors for dyspepsia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dyspepsia, defined as chronic or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen, is a common symptom in the general population and a frequent complaint among subjects seeking medical care.

The prevalence of dyspepsia is between 10% and 40% [1–15]. This variation in prevalence is probably related to differences in defining dyspepsia, particularly regarding the overlap between heartburn and upper abdominal pain or discomfort. Published studies on dyspepsia used different definitions and most of them do not differentiate dyspepsia from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). For example, the annual prevalence of dyspepsia in the United States and other Western countries is approximately 25%, but if frequent heartburn is also considered, the prevalence approaches 40% [10, 14, 16, 17]. This emphasizes the critical point that the definition of dyspepsia remains controversial [11]. However, the most widely used definition of dyspepsia is chronic or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen, defined by the Rome Working Teams [18]. Patients with predominant or frequent (more than once a week) heartburn or acid regurgitation should be considered to have GERD [12].

It is well known that only one quarter of the subjects with dyspepsia seek medical care [10, 14, 19–25]. Despite this fact, patients with dyspepsia account for 2–3% of consultations with general practitioners and for up to 40% of consultations with gastroenterologists [26–28]. The few studies carried out in primary care showed that patients consulting a general practitioner had clinical and demographic features different from those consulting a specialist and from those who did not seek medical care [27, 28]. Therefore, clinic-based samples are not representative of subjects in the community with dyspepsia. These findings suggest that dyspepsia should be evaluated in population-based studies to avoid selection bias.

There are many published studies about the prevalence of dyspepsia in Western countries. However, to our knowledge, very few of these studies are from South/Latin America. Moreover, a number of potential risk factors like sociodemographic variables, biological characteristics, and lifestyle habits have been evaluated, but results are conflicting [8, 9, 13, 15, 22, 29–32]. Therefore, we consider of interest the epidemiologic data about uninvestigated dyspepsia in Argentina.

The aim of our study is to assess the prevalence, severity of symptoms, and risk factors for uninvestigated dyspepsia in a population-based study in Argentina.

Subjects and methods

Study population

The survey sample was stratified by gender, age, geographical area, and size of town of residence, in proportion to the number of inhabitants recorded for each Argentinean population stratum by the 1991 National Population Census (data provided by Argentine Bureau of Statistics and Census). The age categories used were 18–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, and 61–80 years. The survey was undertaken in 17 representative geographical areas with different population densities (Fig. 1).

Sample selection was population based. Location selection was made in private and public companies with a staff large enough so as to achieve the established sample size. From each chosen company, only working individuals were included. Elderly people were enrolled from community centers for retired people. Study population from each area was consecutively enrolled and the rate of individuals unwilling to participate was recorded. In those cases in which consent was forthcoming, respondents were questioned about their age and gender and, provided that they corresponded to the establish stratum, the questionnaire was submitted. Overall data were controlled every 100 loaded surveys to establish consistency and interpretation agreement.

The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Nacional “Profesor Alejandro Posadas” formally approved the study. Subjects’ data were handled according to the guidelines established by the ethics committee. The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Questionnaire

The tool used for this survey was the gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire (GERQ) validated by Locke et al. in 1994 [33] and validated for use in the Spanish population by Moreno Elola-Olaso et al. in 2002 [34]. This questionnaire was used in a recently published study of dyspepsia [15]. It was adapted with minimal modifications to our habits; for example, a decimal system, and was probed with a pilot test in which the usefulness of the tool was measured on individuals with at least 7 years of education. The Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) is the owner of the original questionnaire and gave written authorization to use it in our country. The questionnaire is a self-report instrument, written in simple and easy-to-understand language. It contains 80 questions and a psychosomatic symptom checklist (PSC), a measure of somatization [35]. The questionnaire evaluates symptoms of heartburn, acid regurgitation, noncardiac chest pain, dyspepsia, dysphagia, and abdominal pain. Only the questions referring to heartburn, acid regurgitation, and dyspepsia were considered for our analysis. The questionnaire grades the frequency and severity of the symptoms experienced over the previous year. There are also questions about sociodemographic variables, biological characteristics, lifestyle habits, and family history of diseases of the esophagus or stomach. The GERQs were sent to all researchers for their distribution. Reminders were also sent via fax at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8. Data collection deadline was established 9 weeks after mailing the survey. Completed questionnaires were sent back to the data processing center and entered into a database.

Operative definitions

Dyspepsia was defined as pain or discomfort (fullness/satiety) centered in the upper abdomen having occurred at least 6 times in the previous year. Dyspepsia without GERD was defined as pain or discomfort (fullness/satiety) centered in the upper abdomen, having occurred at least 6 times in the previous year excluding subjects with gastroesophageal reflux. GERD was defined as heartburn or acid regurgitation having occurred at least once per week in the previous year. Heartburn was defined as a burning feeling that rises through the chest. Acid regurgitation was defined as liquid coming back into the mouth and leaving a bitter or sour taste. We also defined a group of subjects constituted by the rest of the subjects who do not meet the criteria of the operative definitions of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux and we called it the no symptom group.

Symptoms severity scale

Symptoms severity was assessed on a 4-point Likert-like scale as follows: mild (they can be ignored), moderate (they cannot be ignored, but they do not modify lifestyle), severe (they modify lifestyle), and very severe (they markedly modify lifestyle).

Measurement of potential risk factors

Information was obtained on sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, and educational level; biological characteristics such as weight and height to calculate the body mass index (BMI); the presence and severity of psychosomatic symptoms (psychosomatic symptom score); lifestyle habits such as smoking, alcohol, coffee, and mate consumption; use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), over-the-counter (OTC) antacids, sucralfate, histamine-2-receptor blockers (H2R blocker), proton pump inhibitors (PPI), and prokinetics. Information was also obtained on physician visits for dyspepsia and on the existence of diseases of the esophagus or stomach in any direct family member (family history) or spouse (environment).

Statistical analysis

To estimate prevalence, each case was weighted according to the size of the sampling fraction. Prevalence percentages were adjusted for gender and age in accordance with the Argentinean population structure according to the 1995 projection based on the 1991 National Census. To compare the demographic and clinical features of the different groups, χ2 tests were used for categorical variables and t-tests were used for continuous variables. To assess the association between dyspepsia and potential risk factors, the presence or absence of each potential risk factor was evaluated separately as the dependent variable in a logistic regression model, adjusted for age, gender, and all remaining risk factors. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each risk factor was calculated from the estimated coefficients in the logistic regression model. To find the best model, a forward stepwise procedure was carried out in such a way that the factor was eliminated from the analysis if the corresponding P > .2. P≤.05 was considered to be statistically significant and all reported P values were 2-sided. Variables were categorically modeled. The categories of the variables are shown in the tables of the Results section. The data were analyzed using the SAS program.

Results

Response rate

A total of 1,000 questionnaires were submitted. One hundred sixty-one subjects refused to participate or returned invalid surveys; 839 returned valid surveys. Thus, the survey response rate was 83.9%.

Prevalence of symptoms

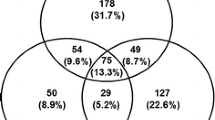

The demographic features of subjects are presented in Table 1. Mean age of subjects was 39.9 years (standard deviation [SD]=15.4; range, 18–77); 466 (55.5%) were women. Overall geographical area-, age-, and gender-adjusted prevalence rates of the different groups of symptoms experienced over the previous year are presented in Fig. 2. Overlap of dyspepsia and GERD was observed. In the group with dyspepsia (n=367), 257 (29.6%; 95% CI, 26.5–32.7) subjects had dyspepsia without GERD and 110 (13.6%; 95% CI, 11.3–15.9) had dyspepsia and GERD.

The overall geographical area-, age-, and gender-adjusted prevalence rate of dyspepsia was 43.2% (95% CI, 39.8–46.6). However, when we excluded subjects with concomitant symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux the overall geographical area-, age-, and gender-adjusted prevalence rate of dyspepsia was 29.6% (95% CI, 26.5–32.7; see Fig. 2). In the dyspepsia group, no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of dyspepsia among age groups were observed. There were significantly more women than men (60.4% versus 39.6%; P=.01); however, there were no statistically significant differences between men and women among age groups. In the group with dyspepsia without GERD, no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of dyspepsia among age groups were observed. There were significantly more women than men (P=.04) in the 41- to 50-year-old group.

Comparisons of demographic features and lifestyle habits between subjects with dyspepsia and subjects with no symptoms are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in age, gender, or BMI; tobacco, coffee, mate, or alcohol consumption; or use of aspirin and NSAIDs. Subjects with dyspepsia had significant more consumption of OTC antacids (P < .0001), sucralfate (P=.03), antisecretory medication (P <.0001), and prokinetics (P < .0001) when compared to subjects with no symptoms. A significantly higher proportion of subjects with dyspepsia reported having a direct family member with diseases of the esophagus or stomach (family history) when compared to subjects with no symptoms (P < .0001). Subjects with dyspepsia had a higher educational level (P=0.001), a significantly higher PSC (P < .0001), and were more likely to have consulted a physician for their symptoms (P < .0001) than subjects with no symptoms.

The group with dyspepsia without GERD consisted of 257 subjects with a mean age of 38.0 years (SD=14.8; range, 19–75); 156 (60.6%) were women. Ulcer-like dyspepsia was present in 183 of 257 (71.1%) subjects, whereas 74 of 257 (28.9%) subjects had dysmotility-like dyspepsia. No statistically significant differences between the genders were observed in dyspepsia subgroups (P=.52). Symptoms were considered as mild in 63 of 257 (24.5%), moderate in 153 of 257 (59.5%), severe in 36 of 257 (14.0%), and very severe in 5 of 257 (1.9%) subjects. Comparisons of demographic features and lifestyle habits between subjects with dyspepsia without GERD and subjects with no symptoms are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in age, gender, or BMI; tobacco, coffee, mate, and alcohol consumption; and use of sucralfate, aspirin or NSAIDs. However, subjects with dyspepsia without GERD reported significantly more consumption of OTC antacids (P=.0001), antisecretory medication (P < .0003), and prokinetics (P=.0025) when compared to subjects with no symptoms. A significantly higher proportion of subjects with dyspepsia without GERD reported having a direct family member with diseases of the esophagus or stomach when compared to subjects with no symptoms (P < .0001). They also had a higher educational level (P=.0001), a significantly higher PSC (P < .0001), and were more likely to have consulted a physician for their symptoms (P=.002) than subjects with no symptoms.

Factors associated with dyspepsia

The results of the logistic regression model considering dyspepsia and dyspepsia without GERD adjusted for age, gender, and each remaining risk factor are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. In this model, a score >14 on the psychosomatic symptom scale (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.88–3.69) and positive family history (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.27–2.55) were significantly and independently associated with dyspepsia symptoms. On the other hand, a score >14 on the psychosomatic symptom scale (OR, 2.52; 95% CI, 1.75–3.61), positive family history (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.19–2.52), and an education level >12 years (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.05–2.29) were significantly and independently associated with dyspepsia without GERD.

Discussion

This nationwide, population-based survey shows that the annual prevalence of dyspepsia in Argentina is 43.2% (95% CI, 39.8–46.6) and the prevalence of dyspepsia without GERD is 29.6% (95% CI, 26.5–32.7). In addition, a score >14 on the psychosomatic symptom scale, positive family history, and an education level >12 years were significantly and independently associated with dyspepsia without GERD.

There are several methodologic issues that could limit this kind of epidemiologic studies. The first is the difficulty in generating truly representative samples of the populations. In this study, the sample survey was selected and stratified according to age, gender, geographical area, and size of town of residence from 17 representative geographical areas of Argentina in proportion to the number of inhabitants recorded for each stratum by the National Population Census to be representative of the entire Argentinean population. Therefore, we do not think that selection bias was a major problem in this study. Thus, we consider that the methodology applied is appropriate for use in population-based studies. A second issue to take into account is the use of a valid questionnaire. This survey was carried out with a validated questionnaire widely employed in the international literature. A pilot study of the GERQ showed good internal consistency, suggesting that the experience of reporting symptoms is not affected by language or cross-cultural differences. Despite the fact that this questionnaire was not specifically validated for dyspepsia, it contains several questions about different upper gastrointestinal symptoms that are indicative of dyspepsia, and these questions have been tested and judged acceptably reliable. Furthermore, the same questionnaire was used in a recently published study of dyspepsia [15]. Last, the high response rate we obtained is likely to avoid significant responder bias.

Although the prevalence of dyspepsia in Argentina is 43.2%, slightly higher than the 10–40% observed in other published studies [1–15], the prevalence of dyspepsia without GERD is 29.6%, considerably higher than the 5–12% reported for population-based studies elsewhere [1–3, 5, 6, 15]. The variability in the published prevalence rates of dyspepsia is probably due to the different definitions applied, the populations studied, and the methods used. Geographical differences in dyspepsia prevalence are difficult to interpret because of diverse methodologies used (definitions, questionnaires, etc.). Despite consensus meetings that have proposed standardized definitions for dyspepsia, there remains controversy particularly about the overlap between reflux symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation) and upper abdominal pain or discomfort [2–6, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 27, 36]. The different definitions used influence the prevalence rates of dyspepsia [2–6, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 27]. The prevalence of dyspepsia is higher if a more inclusive definition of dyspepsia is used; when the definition is restricted to subjects with only upper abdominal pain or discomfort, a lower prevalence rate is obtained. Therefore, studies applying different definitions of dyspepsia are not comparable. The most widely applied definition of dyspepsia is chronic or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen, defined by the Rome Working Teams [18]. Patients with predominant or frequent (more than once a week) heartburn or acid regurgitation should be considered to have GERD [12].

Only one study in Western countries used methodology comparable to ours; therefore, the results can be compared [15]. Our prevalence rates of dyspepsia and dyspepsia without GERD are higher than those recently obtained by Shaib and El-Serag [15] (43.2 % versus 31.9% for dyspepsia, and 29.6% versus 15.8% for dyspepsia without GERD).

In our study, there was considerable overlap between dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux. Approximately 30% of the subjects with dyspepsia had concomitant reflux symptoms. Previous reports obtained similar results, although they reported higher rates of overlap between symptoms. This highlights the importance of the definition of dyspepsia. In our study, in agreement with other studies, when we used a stricter definition of dyspepsia, its prevalence decreased.

In the present study, about 75% of dyspeptic subjects reported symptom severity as moderate or worse, in agreement with the findings of other studies [18, 37, 38]. Unfortunately, studies evaluating symptom severity are sparse [18, 23, 37, 38] and most of them only evaluate this issue in relation with health care seeking [10, 18, 21, 39]. In our study, dyspeptic symptoms interfered in daily activities in a significant proportion of subjects. Therefore, the impact of dyspepsia symptoms on daily activities should be taken into account.

Our results show an association between dyspepsia without GERD and potential risk factors, namely a score >14 on the psychosomatic symptom scale, positive family history, and an education level >12 years. Few studies have evaluated potential risk factors using multivariate analysis [3, 6, 8, 9, 13, 15, 31]. The study of Shaib and El-Serag [15] showed only a trend toward an association with older age (>45 years) in the multiple regression analysis of subjects with functional dyspepsia. Unfortunately, the PSC was not evaluated in their study. The association between a higher PSC and dyspepsia without GERD found in our study is in line with the findings in other populations [2, 3]. The psychosomatic symptom score is a measure of somatization and may conceivably incorporate part of the psychological factors associated with dyspepsia [23]. The consistency of this association in different populations adds credibility to the role of the psychological distress and, specifically, somatization as an independent risk factor for dyspepsia. We chose a cutoff of 14 for the PSC to include it as a dichotomous variable (≤14 and >14) in the logistic regression analysis, based on the differences between the median scores in subjects with symptoms (PSC=22.5 for dyspepsia, PSC=19 for dyspepsia without GERD) and in subjects without symptoms (PSC=13) in our population.

Our results showed an association between having a direct family member with diseases of the esophagus or stomach (positive family history) and dyspepsia without GERD, in agreement with the findings of Berensen et al. [13]. This association might suggest a familial aggregation component in the disorder. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no theories of inheritance of dyspepsia. We have not found any satisfactory explanation for this association so far. Further studies are needed to confirm this finding.

In our study, a higher educational level was associated with dyspepsia without GERD as suggested by Agreus et al. [6], but in contrast with the results reported by other authors [8, 22, 32]. However, their definition of dyspepsia was different from ours and their studies were not population based.

Therefore, we consider that the higher psychosomatic symptom score, the higher prevalence of a family history of diseases of the esophagus or stomach and the higher educational level, would explain, at least partly, the higher prevalence of dyspepsia symptoms in Argentina.

Finally, in our study, no independent associations were found between BMI; smoking habits; coffee, mate, or alcohol consumption; or use of aspirin, NSAIDs, or antisecretory medications. These data are consistent with several studies in which no association was observed between dyspepsia and lifestyle habits [3, 9, 31]. In contrast, some studies showed an association between the use of aspirin or NSAIDs, smoking habits, and dyspepsia [8, 13, 27, 32]. A possible explanation is that our study was underpowered to show this association; those studies were larger than ours.

One of the limitations of population-based studies of dyspepsia is that the underlying causes of dyspepsia cannot be determined. However, it has been shown that most people with dyspepsia in the community suffer from functional dyspepsia, because they do not have a peptic ulcer, reflux esophagitis, or cancer on endoscopy [10, 17, 19, 27].

In summary, dyspepsia and dyspepsia without GERD are especially prevalent in Argentina. In a significant proportion of dyspeptic subjects, the severity of symptoms interferes with daily activities. A higher psychosomatic symptom score, positive family history of diseases of the esophagus or stomach, and a higher education level are significantly and independently associated with dyspepsia without GERD.

References

El-Serag HB, Talley NJ (2004) Systematic review: the prevalence and clinical course of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 19:643–654

Castillo EJ, Camilleri M, Locke III, et al. (2004) A community-based, controlled study of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2:985–996

Kay L, Jorgensen T (1994) Epidemiology of upper dyspepsia in a random population. Prevalence, incidence, natural history, and risk factors. Scand J Gastroenterol 29:2–6

Jones RH, Lydeard SE, Hobbs FD, et al. (1990) Dyspepsia in England and Scotland. Gut 31:401–405

Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Nyren O, et al. (1994) The epidemiology of abdominal symptoms: Prevalence and demographic characteristics in a Swedish adult population. A report from the Abdominal Symptom Study. Scand J Gastroenterol 29:102–109

Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Nyren O, et al. (1995) Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology 109:671–680

Berensen B, Johnsen R, Straume B, et al. (1990) Towards a true prevalence of peptic ulcer: The Sorreisa gastrointestinal disorder study. Gut 31:989–992

Moayyedi P, Forman D, Braunholtz D, et al. (2000) The proportion of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the community associated with Helicobacter pylori, lifestyle factors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Gastroenterol 95:1448–1455

Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, et al. (1994) Smoking, alcohol, and analgesics in dyspepsia and among dyspepsia subgroups: Lack of an association in a community. Gut 35:619–624

Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, et al. (1992) Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: A population-based study. Gastroenterol 102:1259–1268

Westbrook JI, McIntosh JH, Talley NJ (2000) The impact of dyspepsia definition on prevalence estimates: considerations for future researchers. Scand J Gastroenterol 3:227–233

Talley NJ, Vakil N, et al. (2005) Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 100:2324–2337

Berensen B, Johnsen R, Straume B, et al. (1996) Non-ulcer dyspepsia and peptic ulcer: The distribution in a population and their relation to risk factors. The Sorreisa gastrointestinal disorder study. Gut 38:822–825

Jones R, Lydeard S (1989) Prevalence of symptoms of dyspepsia in the community. Br Med J 298:30–32

Shaib Y, El-Serag HB (2004) The prevalence and risk factors of functional dyspepsia in a multiethnic population in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 99:2210–2216

Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett S, et al. (1997) Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux in the community. Gastroenterol 112:1448

Talley NJ, Silverstein MD, Agreus L et al. (1998) AGA technical review: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterol 114:582–595

Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, et al. (2000) Functional gastroduodenal disorders. In: Drossman DA, ed. Rome II: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. Degnon, McLean, VA, pp. 299–350

Talley NJ, Boyce P, Jones M (1998) Dyspepsia and health care seeking in a community. How important are psychological factors?. Dig Dis Sci 43:1016–1022

Drossman DA, Li Zhiming, Andruzzi E, et al. (1993) US Householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography and health impact. Dig Dis Sci 38:1569–1580

Ahlawat SK, Locke GR, Weaver Al, et al. (2005) Dyspepsia consulters and patterns of management: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 22:251–259

Holtmann G, Goebell H, Talley NJ (1994) Dyspepsia in consulters and non-consulters: Prevalence, health-care seeking behaviour and risk factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 6:917

Stanghellini V (1999) Relationship between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and lifestyle, psychosocial factors and comorbidity in the general population: results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol 34(Suppl 231):29–37

Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Huskic SS, et al. (2003) Predictors of conventional and alternative health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 17:841–851

Holtmann G, Goebell H, Holtmann M, et al. (1994) Dyspepsia in healthy blood donors. Pattern of symptoms and association with Helicobacter pylori. Dig Dis Sci 39:1090–1098

Knill-Jones RP (1991) Geographical differences in the prevalence of dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol 26(Suppl 182):17

Talley N, Collin-Jones F, Kock KL, et al. (1991) Functional dyspepsia: a classification with guidelines for diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Int 4:45–160

Lydeard R, Jones R (1989) Factors affecting the decision to consult dyspepsia: Comparison of consulters and non-consulters. J R Coll Gen Pract 39:495–498

Talley NJ, McNeil D, Piper DW (1998) Environmental factors and chronic unexplained dyspepsia: association with acetaminophen but not other analgesics, coffee, tea, or smoking. Dig Dis Sci 33:641–648

Elta GH, Behler EM, Colturi TJ (1990) Comparison of coffee intake and coffee induced symptoms in patients with duodenal ulcer, non-ulcer dyspepsia and normal controls. Am J Gastroenterol 85:1339–1342

Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, et al. (1994) Smoking, alcohol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in outpatients with functional dyspepsia and among dyspepsia subgroups. Am J Gastroenterol 89:524–528

Nandurkar S, Talley NJ, Xia H, et al. (1998) Dyspepsia in the community is linked to smoking and aspirin use but not to Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Intern Med 158:1427–1433

Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, et al. (1994) A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc 69:539–547

Moreno Elola-Olaso C, Rey E. Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Locke GR III, Diaz Rubio M (2002) Adaptation and validation of a gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire for use on a Spanish population. Rev Esp Enf Dig 94:745–751

Attanasio V, Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, Arena JG (1984) Psychometric properties of the SUNYA revision of the psychosomatic symptom checklist. J Behav Med 7:247–258

Barbara L, Camilleri M, Corinaldesi R, et al. (1989) Definition and investigation of dyspepsia. Consensus of an international ad hoc Working Party. Dig Dis Sci 34:1272–1276

Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, et al. (1999) Predominant symptoms identify different subgroups in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 94:2080–2085

Maconi G, Tosetti C, Stanghellini V, et al. (2004) Dyspeptic symptoms in primary care. An observational study in general practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 14:985–990

Jones R, Lydeard (1992) Dyspepsia in the community: A follow-up study. Br J Clin Pract 45:95–97

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thanks Mayo Clinic for granting permission to use the Gastro-esophageal Reflux Questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olmos, J.A., Pogorelsky, V., Tobal, F. et al. Uninvestigated Dyspepsia in Latin America: A Population-Based Study. Dig Dis Sci 51, 1922–1929 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-006-9241-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-006-9241-y