Abstract

Background

Pathological examination of a minimum of 16 lymph nodes is recommended following surgery for gastric adenocarcinoma, despite this a longer survival is expected when 30 or more lymph nodes are examined. Small lymph nodes are difficult to identify, and fat-clearing solutions have been proposed to improve this, but there is no evidence of their clinical benefit.

Methods

Fifty D2 subtotal gastrectomy specimens were randomized for fixation in Carnoy’s solution (CS) or 10 % neutral buffered formalin (NBF), with subsequent fat dissection. After dissection, the residual fat from the NBF group, instead of being discarded, was immersed in CS and dissected again. Data from 25 D2 subtotal gastrectomies performed before the study were also analyzed.

Results

The mean number of examined lymph nodes was 50.4 and 34.8 for CS and NBF, respectively (p < 0.001). Missing lymph nodes were found in all cases from the residual fat group (mean of 16.9), and in eight of them (32 %) metastatic lymph nodes were present; this allowed the upstaging of two patients. Lymph nodes in the CS group were smaller than those in the NBF group (p = 0.01). The number of retrieved lymph nodes was similar among the NBF and Retrospective groups (p = 0.802).

Conclusions

Compared with NBF, CS increases lymph node detection following gastrectomy and allows a more accurate pathological staging. No influence of the research protocol on the number of examined lymph nodes was observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lymph node (LN) resection is essential for patients with gastric adenocarcinoma undergoing gastrectomy. It allows regional disease control and pathological TNM staging. Accurate staging is fundamental for prognosis and identification of those patients who should be referred for adjuvant therapy. The N status from the TNM classification strongly correlates with survival, and postoperative dissection of the specimen in the search for resected LNs should be diligently performed [1–5]. It is recommended that at least 16 LNs should be examined following a gastrectomy for gastric cancer [6]. However, the number of examined LNs is an independent prognostic factor, and longer survival is expected for patients with 30 or more LNs examined [7–11]. This is observed even for patients with early gastric cancer, and an explanation could be the understaging of those with a lower number of examined LNs owing to insufficient lymphadenectomy (leaving compromised LNs in the patient) or inadequate pathological analysis (missing resected metastatic LNs that would otherwise change the TNM classification) [6, 8, 12].

Once the surgical team has been well trained and performs lymphadenectomy satisfactorily, attention should be given to the analysis of the surgical specimen. Finding LNs in the perivisceral fat is a demanding task, and small LNs may pass unnoticed even by dedicated people [13–17]. To improve this, LN-revealing solutions (LNRS) have been proposed, but to date there are no irrefutable data indicating their clinical benefit [13].

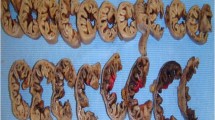

Carnoy’s solution (CS) is a tissue fixative that consists of ethanol (60 %), chloroform (30 %), and glacial acetic acid (10 %) [18]. It can be used as an LNRS, since the ethanol extracts phospholipids from the cells, allowing the LNs to stand out as pale nodules (Fig. 1) [19]. Our group previously compared CS with 10 % neutral buffered formalin (NBF) following D1 gastrectomy in cadavers, and observed that CS significantly increased the total number of examined LNs [19]. These findings inspired the present study.

Objectives

The objectives were as follows:

-

1.

To compare CS and NBF concerning the total number of examined LNs

-

2.

To verify if surgically retrieved LNs are lost with the routine NBF fixation and dissection, and if this is clinically relevant

-

3.

To compare the duration of the dissection with CS and NBF

-

4.

To compare the size of the examined LNs obtained with CS and NBF

-

5.

To observe if the research protocol influenced the number of retrieved LNs

Methods

Study design

Fifty specimens from subtotal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma were randomized for fixation in CS or NBF with subsequent LN dissection. Following dissection, the residual fat from the NBF group was immersed in CS and redissected, providing a third study group (Revision group). Figure 2 presents the study flowchart.

Data from the most recent 25 D2 subtotal gastrectomies performed before the study were also analyzed (Retrospective group).

Surgical procedures were performed by five specialized surgeons who remained blind to the randomization of the specimens.

Sample calculation

To calculate the sample size, a pilot study was performed. Twenty cases were randomized for fixation in CS or NBF. The difference in the number of examined LNs after dissection was 14.4 favoring CS. From the highest standard deviation observed (16.3) and a power of 80 %, n was estimated in 42 cases. This was rounded to 50 to increase the study power to 85 %. Since the method was not modified, these 20 cases were included in the final study.

Eligibility criteria

Only specimens from patients with gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent D2 subtotal gastrectomy were included. Figure 3 presents the selection criteria. The Retrospective group was selected using the same restrictions.

Pathological examination

Specimens were randomized after the procedure. The perivisceral fat was removed from the stomach and the gastric LN stations were identified and sent to the pathology department separately. The perigastric fat was not violated for T3 lesions infiltrating the gastrocolic or gastrohepatic ligaments, since compromising the serosa might upstage the lesion to T4.

The LN stations were fixed in the selected solution for 24–48 h, and were then dissected by visualization, palpation, and sectioning. All nodular structures found were sent for histologic analysis. The same pathology assistant dissected all specimens. Pathological processing and analysis was performed as recommended by the College of American Pathologists [20].

Outcomes

The total number of examined LNs was the primary end point of the study. They were counted by two different pathologists under light microscopy. Count discrepancies were verified by a third pathologist. The dissection duration was measured in minutes from the moment the LN stations were removed from the fixative until the end of the procedure. LNs were measured in millimeters with the same ruler by the same pathology assistant responsible for the dissection.

Hazard

Concerning workplace and worker safety, the same requirements needed for NBF apply to CS. Storage, transportation, and disposal are similar, skin and eye contact should be avoided, and both solutions should be handled under a fume hood [21–23].

The occupational exposure limits in an 8-h shift are 1 ppm (1.2 mg/m3) for NBF and 2 ppm (9.9 mg/m3) for CS (chloroform). Additionally, NBF is a known carcinogen, whereas CS (chloroform) is a probable carcinogen [21–23].

Randomization and statistical analysis

Randomization was computer generated using SAS® Enterprise Guide® version 4.3. The results were analyzed using Student’s t test for normally distributed data and the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test for nonnormally distributed data. We considered p < 0.05 as significant.

Ethics

The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee. All possible candidates to be included in the study signed an informed consent form the day before they underwent surgery.

Results

Since the specimens were included in the study only after the procedure, no case was lost. CS and NBF groups were similar in terms of age, gender, BMI, and Lauren’s histologic type (Table 1).

The duration of the dissection was similar for the CS and the NBF groups (p = 0.114). The Revision group required 28.7 min (mean). The dissection time for the NBF plus revision group was approximately 78 min (mean), which is statistically different from the dissection time for the CS group and/or NBF-alone group (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

The mean number of examined LNs was 50.4 and 34.8 for the CS and NBF groups, respectively (p < 0.001). As for the Revision group, a mean of 16.9 LNs was found, whereas the NBF plus revision group had a mean of 51.7 LNs, which is similar to that for the CS group (p = 0.809) (Table 1).

For the Revision group, LNs were found in all cases (ranging from one to 47). With the exception of one 7 mm LN, all other 421 LNs encountered were 3 mm or smaller. Eight patients (32 %) had metastatic LNs, and two of them (8 %) were upstaged (Table 2). As observed in Table 3, all 13 compromised LNs found in this group were 3 mm or smaller, and eight of them had micrometastasis (tumor cell clusters measuring 0.2–2.0 mm in their greatest dimension).

Small LNs (less than 5 mm) were more frequent in the CS group than in the NBF group (p = 0.01) (Table 1). The Retrospective group was similar to the NBF group in terms of age, gender, and BMI. The number of examined LNs was also similar (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Considering that 0.5 l of fixative solution was used per case, CS was US$1.22 more expensive per specimen analyzed. At the time of writing, the average price in Brazil for 1 l of CS and NBF was US$8.16 and US$5.72, respectively.

Discussion

Pathological assessment of gastrectomy specimens is an essential step in the evaluation of gastric cancer patients, allowing their categorization into groups with distinct treatment and prognosis [1–5, 24]. During this analysis, small LNs are particularly difficult to find, and missing them may negatively impact the patient’s life expectancy, since even micrometastasis reduces survival [25–29]. Noda et al. [29] reported that if all LNs smaller than 6 mm were ignored, 15 % of their patients would have been understaged. To improve the detection of these small LNs, LNRS have been proposed. Despite their promise, experience with these solutions in gastric cancer has been dismal and controversial [13]. Of the four articles currently available, all have methodological limitations (e.g., small sample size), and only one retrieved an adequate number of LNs with fresh dissection [14–17]. These studies had a similar design with fresh dissection of the LNs followed by immersing the residual fat in an LNRS, with subsequent redissection. Two constant observations were the solution’s ability to find small LNs and its capacity to increase the number of retrieved LNs. Nevertheless, these findings cannot be considered clinically significant, since there was no upstaging for any patient in the only study with an adequate number of retrieved LNs following fresh dissection [17].

Currently, the pathological routine in our service differs slightly from the one recommended by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association [30]: whereas the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association proposes fresh dissection of the LNs, we remove the perivisceral fat from the stomach, separate and identify the LN stations by fresh dissection, and then all material is immersed in a fixative solution for 24–48 h. After this, the specimen is dissected in the search for LNs. In our service the number of examined LNs was similar with both approaches (fresh dissection and postfixation dissection), being also equivalent to the numbers reported by other reference centers worldwide [31–33]. Maintenance of our routine during the study allowed us to verify a possible influence of the research protocol on the number of examined LNs.

Concerning the study design, the analysis of the residual fat from the NBF group permitted us to verify if resected LNs were being lost with the routine pathological approach. It also resolved the ethical concern that an increased number of LNs was expected in the CS group.

The time spent in LN dissection was similar for the CS and NBF groups (around 40–50 min), suggesting a similar dedication of the pathology assistant for both groups. However, since more LNs were obtained with CS, it might be considered that this solution speeds up dissection.

Considering the total number of examined LNs, the effectiveness of CS was superior to that of NBF alone and was similar to that of NBF plus CS (NBF plus revision group). To interpret this, attention should be given to the size of the examined LNs: CS resulted in a significantly higher number of LNs smaller than 5 mm when compared with NBF. Additionally, with the exception of one 7 mm LN, all others found in the Revision group (residual fat from the NBF group) were 3 mm or smaller, demonstrating that these very small LNs are the ones being lost with the routine approach (NBF fixation with subsequent dissection) and can be found with CS.

Analysis of the Revision group revealed that LNs were being lost in all specimens of the NBF group. In fact, in eight patients (32 %), metastatic LNs were passing unnoticed with the routine approach. For two patients (8 %) this analysis resulted in upstaging, and since both already had other positive LNs, only their prognosis changed. It might be expected that in a larger sample, N0 patients may be upstaged to N+, implying a change in their treatment (with indication of adjuvant therapy) and adding more clinical significance to the present study.

The finding of a similar number of examined LNs between the NBF and Retrospective groups implies that no influence of the study protocol over the pathology assistant responsible for the dissection occurred. It also adds external validity to the study, since different members of the pathology team dissected the specimens in the Retrospective group.

Some measures were taken to ensure the internal validity of the study. Groups were randomly distributed and specimen allocation was performed only after the surgical procedure. The research was conducted in a reference center, and only highly trained surgeons operated on the patients. To control other surgically related variables, only standard D2 subtotal gastrectomy was considered and patients with previous gastric (or omentum) surgical procedures were excluded, as were those who underwent neoadjuvant therapy or with previous radiotherapy on the upper abdomen. To standardize LN dissection, the same pathology assistant was responsible for all cases. Identified LNs were verified by a second pathologist to avoid counting errors. The same eligibility criteria from the prospective cases applied to the retrospective cases.

Among the limitations of the study, although statistically significant, the number of included cases is relatively small. Research was unicentric and the accuracy of fresh dissection was not assessed. The pathology assistant was always aware of the randomization (both solutions have distinct and characteristic odors), but the duration of the dissection and the retrospective analysis suggest that there was no influence of knowing the allocation. Not analyzing the residual fat from the CS group could be a limitation, but finding the same number of LNs in the CS and NBF plus revision groups makes this fact irrelevant.

Finally, CS is safe to use, having the same storage and manipulation requirements as NBF. It is also economically accessible, being only slightly more expensive than NBF (US$1.22 per patient), but with the benefit of increased accuracy at pathological staging.

In conclusion, when compared with widely used NBF, CS increases the number of retrieved LNs in gastrectomy specimens for gastric adenocarcinoma. The duration of the dissection is similar for both solutions, with a higher number of small LNs being obtained with CS. Additionally, small LNs are lost during the dissection of NBF-fixed specimens, and this is clinically relevant, since they may contain metastasis modifying the staging of the patient. The use of a research protocol did not influence the number of retrieved LNs in this study.

References

Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16(1):1–27.

Reim D, Loos M, Vogl F, Novotny A, Schuster T, Langer R, et al. Prognostic implications of the seventh edition of the international union against cancer classification for patients with gastric cancer: the Western experience of patients treated in a single-center European institution. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(2):263–71.

Marrelli D, Morgagni P, de Manzoni G, Coniglio A, Marchet A, Saragoni L, et al. Prognostic value of the 7th AJCC/UICC TNM classification of noncardia gastric cancer: analysis of a large series from specialized Western centers. Ann Surg. 2012;255(3):486–91.

Kikuchi S, Futawatari N, Sakuramoto S, Katada N, Yamashita K, Shibata T, et al. Comparison of staging between the old (6th edition) and new (7th edition) TNM classifications in advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(6):2361–5.

Fang WL, Huang KH, Chen JH, Lo SS, Hsieh MC, Shen KH, et al. Comparison of the survival difference between AJCC 6th and 7th editions for gastric cancer patients. World J Surg. 2011;35(12):2723–9.

Ichikura T, Ogawa T, Chochi K, Kawabata T, Sugasawa H, Mochizuki H. Minimum number of lymph nodes that should be examined for the International Union Against Cancer/American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification of gastric carcinoma. World J Surg. 2003;27(3):330–3.

Xu D, Huang Y, Geng Q, Guan Y, Li Y, Wang W, et al. Effect of lymph node number on survival of patients with lymph node-negative gastric cancer according to the 7th edition UICC TNM system. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38681.

Kesley R, Correa JHS, Castro L, Souza-Filho O, Oliveira IM, Pinto CE, et al. Lymph nodes number in surgical specimen modifies prognosis in advanced stage gastric cancer patients- study of the Will-Rogers phenomenon. Appl Cancer Res. 2005;25(3):122–9.

Baiocchi GL, Tiberio GA, Minicozzi AM, Morgagni P, Marrelli D, Bruno L, et al. A multicentric Western analysis of prognostic factors in advanced, node-negative gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):70–3.

Seevaratnam R, Bocicariu A, Cardoso R, Yohanathan L, Dixon M, Law C, et al. How many lymph nodes should be assessed in patients with gastric cancer? A systematic review. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15(Suppl 1):S70–88.

Huang CM, Lin JX, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB. Impact of the number of dissected lymph nodes on survival for gastric cancer after distal subtotal gastrectomy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:476014. doi:10.1155/2011/476014.

Wagner PK, Ramaswamy A, Ruschoff J, Schmitz-Moormann, Rothmund M. Lymph node counts in the upper abdomen: anatomical basis for lymphadenectomy in gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1991;78(7):825–7.

Abbassi-Ghadi N, Boshier PR, Goldin R, Hanna GB. Techniques to increase lymph node harvest from gastrointestinal cancer specimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Histopathology. 2012;61(4):531–42.

Candela FC, Urmacher C, Brennan MF. Comparison of the conventional method of lymph node staging with a comprehensive fat-clearing method for gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1990;66(8):1828–32.

Koren R, Kyzer S, Levin L, Klein B, Halpern M, Rath-Wolfson L, et al. Lymph node revealing solution: a new method for lymph node sampling: results in gastric adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 1998;5(2):341–4.

Siqueira PR, Nadal SR, Santo GC, Silva MM, Rodrigues FCM, Malheiros CA. Efficacy of lymph nodes revealing solution in gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy specimens from gastric carcinoma. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2000;27(4):221–6.

Luebke T, Baldus SE, Zirbes TK, Pham TD, Schneider PM, Dienes HP, et al. Lymph node revealing solution in gastric carcinoma does not provide upstaging of the N-status. Oncol Rep. 2005;13(2):361–5.

Pereira MA, Dias AR, Faraj SF, Cirqueira CS, Tomitao MT, Carlos Nahas S, et al. Carnoy’s solution is an adequate tissue fixative for routine surgical pathology, preserving cell morphology and molecular integrity. Histopathology. 2014. doi:10.1111/his.12532

Luz DA, Ribeiro U Jr, Chassot C, Collet E Silva F de S, Cecconello I, Corbett CE. Carnoy’s solution enhances lymph node detection: an anatomical dissection study in cadavers. Histopathology. 2008;53(6):740–2.

Compton C, Sobin LH. Protocol for the examination of specimens removed from patients with gastric carcinoma: a basis for checklists. Members of the Cancer Committee, College of American Pathologists, and the Task Force for Protocols on the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Gastric Cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122(1):9–14.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US). Toxicological profile for chloroform [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. 1997. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp6.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US). Toxicological profile for Formaldehyde [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. 1999. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp111.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2014.

American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. Threshold limit values (TlVs) for chemical substances and physical agents and biological exposure indices (BEIs). Cincinnati: ACGIH. 2001.

Roth AD. Curative treatment of gastric cancer: towards a multidisciplinary approach? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;46(1):59–100.

Dell’Aquila NF Jr, Lopasso FP, Falzoni R, Iriya K, Gama-Rodrigues J. Prognostic significance of occult lymph node micrometastasis in gastric cancer: a histochemical and immunohistochemical study based on 1997 UICC TNM and 1998 JGCA classifications. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2008;21(4):164–9.

Wu ZY, Li JH, Zhan WH, He YL, Wan J. Effect of lymph node micrometastases on prognosis of gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4122–5.

Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Nakajo A, Higashi H, Watanabe T, et al. Clinical impact of micrometastasis of the lymph node in gastric cancer. Am Surg. 2003;69(7):573–7.

Yasuda K, Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Inomata M, Takeuchi H, Kitano S. Prognostic effect of lymph node micrometastasis in patients with histologically node-negative gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(8):771–4.

Noda N, Sasako M, Yamaguchi N, Nakanishi Y. Ignoring small lymph nodes can be a major cause of staging error in gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85(6):831–4.

Association Japanese Gastric Cancer. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14(2):113–23.

Cecconello I, Coimbra BG, Jacob CE, Bresciani C, Lopasso FP, Ribeiro-Junior U, Yagi OK, Mucerino DR, Zilberstein B. Results of D2 gastrectomy for gastric cancer: lymph node chain dissection or multiple node resection? Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2012;25(3):161–4.

Bunt AM, Hermans J, van de Velde CJ, Sasako M, Hoefsloot FA, Fleuren G, et al. Lymph node retrieval in a randomized trial on western-type versus Japanese-type surgery in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(8):2289–94.

Chen K, Xu XW, Mou YP, Pan Y, Zhou YC, Zhang RC, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;8(11):182.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dias, A.R., Pereira, M.A., Mello, E.S. et al. Carnoy’s solution increases the number of examined lymph nodes following gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a randomized trial. Gastric Cancer 19, 136–142 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0443-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0443-2