Abstract

Background

According to the literature, the conversion rate for laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) after endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) for cholecystodocholithiasis reaches 20%, at least when LC is performed 6 to 8 weeks afterward. It is hypothesized that early planned LC after ES prevents recurrent biliary complications and reduces operative morbidity and hospital stay.

Methods

All consecutive patients who underwent LC after ES between 2001 and 2004 were retrospectively evaluated. Recurrent biliary complications during the waiting time for LC, conversion rate, postoperative complications, and hospital stay were documented.

Results

This study analyzed 167 consecutive patients (59 men) with a median age of 54 years. The median interval between ES and LC was 7 weeks (range, 1–49 weeks). During the waiting time for LC, 33 patients (20%) had recurrent biliary complications including cholecystitis (n = 18, 11%), recurrent choledocholithiasis (n = 9, 5%), cholangitis (n = 4, 2%), and biliary pancreatitis (n = 2, 1%). Of these 33 patients, 15 underwent a second endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC). The median time between ES and the development of recurrent complications was 22 days (range, 3–225 days). Most of the biliary complications (76%) occurred more than 1 week after ES. Conversion to open cholecystectomy occurred for 7 of 33 patients with recurrent complications during the waiting period, compared with 13 of 134 patients with an uncomplicated waiting period (p = 0.14). This concurred with doubled postoperative morbidity (24% vs 11%; p = 0.09) and a longer hospital stay (median, 4 vs 2 days; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

In this retrospective analysis, 20% of all patients had recurrent biliary complications during the waiting period for cholecystectomy after ES. These recurrent complications were associated with a significantly longer hospital stay. Cholecystectomy within 1 week after ES may prevent recurrent biliary complications in the majority of cases and reduce the postoperative hospital stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Of the patients presenting with cholecystolithiasis, 4% to 15% have concomitant common bile duct (CBD) stones [1–3]. The current standard of treatment for symptomatic CBD stones is endoscopic decompression of the CBD and removal of the stones. Decompression may be achieved by endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES), papillary dilation, nasobiliary drainage, or biliary stenting.

For patients with residual stones in the gallbladder after endoscopic stone removal, the subsequent management of the gallbladder has been subject to debate. Many authors have advocated a wait-and-see policy after ES for these patients because only an estimated 10% of them experience recurrent biliary symptoms in retrospective and nonrandomized studies [4–8]. However, in two prospective randomized trials, up to 47% of the patients presented with recurrent biliary symptoms after a wait-and-see policy, and the cumulative risk for death was 21% within 5 years (vs 5.8% for patients allocated to planned cholecystectomy) [9, 10].

Single-stage treatment by laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) combined with laparoscopic CBD exploration has been introduced as a daring alternative for combined endoscopic and surgical treatment. Despite a recent Cochrane review and a metaanalysis showing comparable results between the two strategies, experience and expertise for the widespread use of laparoscopic CBD exploration still are lacking [11, 12]. Thus, in many countries, patients who undergo ES for CBD-stones are subsequently scheduled for cholecystectomy.

The interval between LC and ES may vary from days to months. In the Netherlands, as in other countries, LC is performed 6 to 9 weeks after ES [9, 10, 13–16]. The performance of LC after ES is associated with a higher conversion rate than experienced by patients with uncomplicated cholecystolithiasis [9, 10, 17]. To evaluate the influence of timing of LC after ES for complicated gallstone disease, we retrospectively reviewed a consecutive patient series with an emphasis on the relation between recurrent biliary complications after ES and conversion rate, operative morbidity, and hospital stay.

Materials and methods

This study was performed in a university hospital and a large affiliated teaching hospital. The hospitals’ digital databases were searched for patients who underwent both ES and cholecystectomy for gallstone disease between 1 January 2001 and 1 January 2005.

All consecutive patients who underwent ES and subsequent (planned) cholecystectomy, both in the same hospital, were included. Patients requiring emergency cholecystectomy within 72 h after ES (n = 6) were excluded from this study because it was considered that elective cholecystectomy never had been planned for these patients.

The variables collected included age at time of ES, gender, date and indication of the first ES, recurrent biliary complaints between ES and elective cholecystectomy, readmissions, endoscopic reintervention during the waiting period, date of emergency cholecystectomy, complications of cholecystectomy (bleeding requiring transfusion, bleeding requiring intervention, bile leakage requiring drainage), conversion rate, hospital stay, and mortality rate. The main outcome parameters were the number of patients with biliary complications during the waiting period for cholecystectomy and the outcome of surgery (conversion rate, morbidity, and postoperative hospital stay). Biliary complications were defined as complications attributable to bile stones leading to cholecystitis, obstructive choledocholithiasis, or acute biliary pancreatitis. Patients with a complicated waiting period were compared with patients who had an uncomplicated waiting period in terms of postoperative complications and hospital stay.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Fisher’s exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare groups. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p value less than 0.05.

Results

Between 2001 and 2005, 167 consecutive patients (59 men) with a median age of 54 years (range, 18–87 years) underwent ES for symptomatic CBD stones followed by cholecystectomy.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) was performed because of suspected CBD stones based on clinical, laboratory, and ultrasonographic data. For all the studied patients, ES was performed after obstructive choledocholithiasis had been proved on ERC. The findings showed that 34 patients also had biliary pancreatitis and that 18 patients had cholangitis. For 81 patients (49%), stones were extracted from the CBD, and for 50 patients (30%), sludge was evacuated. One patient was treated with a nasobiliary drain, and four patients (2%) had biliary stenting.

Waiting period

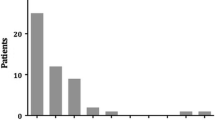

The median time between ES and planned LC was 7 weeks (range, 1–49 weeks). During the waiting period, 33 (20%) of 167 patients experienced recurrent biliary complications (Table 1), including 18 patients with acute cholecystitis (11%), 9 with recurrent choledocholithiasis (5%), 4 with cholangitis (2%), and 2 with biliary pancreatitis (1%).

These biliary complications needed the following interventions: endoscopic reintervention for 16 patients and emergency cholecystectomy for 24 patients (Table 1). The median time until the development of recurrent biliary complaints after ES was 22 days (range, 3–225 days), and 76% of the biliary complications occurred more than 1 week after ES. Age, gender, and the indication for initial ES did not differ between the patients with and those without a complicated waiting period (data not shown).

Cholecystectomy

The surgery for all the patients was performed by surgeons or surgical residents under supervision. Open cholecystectomy was performed primarily for 7 patients (4%) because of a previous colostomy (n = 2), a retained CBD stone (n = 1), diffuse peritonitis (n = 2), pancreatic necrosis (n = 1), or subphrenic abscess (n = 1). For the remaining 160 patients, the overall conversion rate for cholecystectomy was 13%. There was a nonsignificant higher conversion rate for patients with a complicated waiting period (21%, 7/33 vs 10%, 14/134; p = 0.14). The reasons for conversion are listed in Table 2.

Postoperative course

The overall postoperative morbidity rate was 14%. Patients with a complicated waiting period had a nonsignificant increase in complications and a longer postoperative hospital stay (Table 3). One patient with an uncomplicated waiting period (1%) experienced bile leakage from the cystic duct compared with three patients with a complicated waiting period (9%). All needed endoscopic stenting. One major bile duct injury was experienced by a patient with an uncomplicated waiting period, requiring laparotomy and CBC reconstruction. Six patients experienced postoperative bleeding during the uncomplicated waiting period group compared with no patients in the complicated group. No reasons for this difference could be found. One of these patients experienced hypovolemic shock due to bleeding from the liver bed requiring relaparotomy. Despite packing to control the bleeding, the patient died in the intensive care ward the same day. Mortality was nil in the complicated waiting period group. The median postoperative hospital stay was 2 days in the uncomplicated waiting period group compared with 4 days in the complicated waiting period group (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study has shown that among patients waiting to undergo cholecystectomy after ES for CBD stones, every fifth patient experiences recurrent biliary events requiring endoscopic reintervention, emergency cholecystectomy, or both. For patients who experienced these recurrent events, the postoperative morbidity, conversion rate, and median postoperative hospital stay were doubled.

The issue of biliary complications recurring in the waiting period for LC and the outcome of surgery were not addressed earlier. Recurrent symptoms and reinterventions not only have an obvious influence on a patient’s well-being, but recurrent symptoms also appear to be associated with increased difficulty of surgery and a more complicated postoperative course. Although conversion to open cholecystectomy is a perioperative problem, it is not regarded as a complication of LC. However, open cholecystectomy is associated with increased postoperative pain, more pulmonary complications and wound infections, and a lengthened hospital stay [18–22]. Thus, diminishing the conversion rate by timely surgery after ES seems worthwhile.

In both randomized trials mentioned earlier, a remarkably high conversion rate was found, not only among patients who underwent cholecystectomy on demand (50%), but also among patients allocated to planned LC. In both trials, conversion to open cholecystectomy was necessary for more than 20% of the patients [9, 10]. In contrast, among patients with uncomplicated gallstone disease (i.e., without CBD stones or need for ES), the conversion rate for LC is known to be 3% to 5% [2, 18, 20, 21, 23–27].

Possibly, the timing of LC after ES may have an influence on the difficulty of surgery. The median time until cholecystectomy in the current study was 7 weeks. The moment of surgery was largely determined by the surgeon who performed the cholecystectomy. In the Netherlands, LC often is planned 6 weeks after ES, partly due to logistic reasons but also because many surgeons believe that surgery is safer several weeks after ES.

The literature has little data for determining the optimal timing of cholecystectomy after ES. Only one study specifically considers the timing of LC after ES in relation to the conversion rate. A significantly higher conversion rate was encountered when LC was performed 2 to 6 weeks after ES, as compared with 1 week after ES [15]. Reports of LC performed within days after ES show conversion rates as low as those for patients with uncomplicated cholelithiasis [2, 16, 28, 29].

Early cholecystectomy after ES may prevent recurrent biliary complications, which are associated with increased postoperative morbidity and prolonged hospital stay. In the current study, up to 76% of these recurrent events may have been prevented by early cholecystectomy (i.e., within 1 week after ES). Furthermore, timely surgery may decrease the conversion rate. A prospective randomized multicenter trial has been initiated to compare early (within 72 h) and late (after 6–8 weeks) cholecystectomy after ES (LANS-trial, ISRCTN42981144).

References

Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC (2004) A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg 239:28–33

Sarli L, Iusco DR, Roncoroni L (2003) Preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the management of cholecystocholedocholithiasis: 10-year experience. World J Surg 27:180–186

Joyce WP, Keane R, Burke GJ, Daly M, Drumm J, Egan TJ, Delaney PV (1991) Identification of bile duct stones in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 78:1174–1176

Hill J, Martin DF, Tweedle DE (1991) Risks of leaving the gallbladder in situ after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones. Br J Surg 78:554–557

Lai KH, Lin LF, Lo GH, Cheng JS, Huang RL, Lin CK, Huang JS, Hsu PI, Peng NJ, Ger LP (1999) Does cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy prevent the recurrence of biliary complications? Gastrointest Endosc 49:483–487

Hammarstrom LE, Holmin T, Stridbeck H (1996) Endoscopic treatment of bile duct calculi in patients with gallbladder in situ: long-term outcome and factors. Scand J Gastroenterol 31:294–301

Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, Fraser I, Fossard DP (1984) The management of common bile duct calculi by endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with gallbladders in situ. Br J Surg 71:69–71

Welbourn CR, Beckly DE, Eyre-Brook IA (1995) Endoscopic sphincterotomy without cholecystectomy for gall stone pancreatitis. Gut 37:119–120

Lau JY, Leow CK, Fung TM, Suen BY, Yu LM, Lai PB, Lam YH, Ng EK, Lau WY, Chung SS, Sung JJ (2006) Cholecystectomy or gallbladder in situ after endoscopic sphincterotomy and bile duct stone removal in Chinese patients. Gastroenterology 130:96–103

Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, Janssen IM, Bolwerk CJ, Timmer R, Boerma EJ, Obertop H, Huibregtse K, Gouma DJ (2002) Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet 360:761–765

Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J (2006) Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003327

Clayton ES, Connor S, Alexakis N, Leandros E (2006) Meta-analysis of endoscopy and surgery versus surgery alone for common bile duct stones with the gallbladder in situ. Br J Surg 93:1185–1191

Schachter P, Peleg T, Cohen O (2000) Interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of acute biliary pancreatitis. HPB Surg 11:319–322, discussion 322–313

Cameron DR, Goodman AJ (2004) Delayed cholecystectomy for gallstone pancreatitis: readmissions and outcomes. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 86:358–362

de Vries A, Donkervoort SC, van Geloven AA, Pierik EG (2005) Conversion rate of laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in the treatment of choledocholithiasis: does the time interval matter? Surg Endosc 19:996–1001

Hamy A, Hennekinne S, Pessaux P, Lada P, Randriamananjo S, Lermite E, Boyer J, Arnaud JP (2003) Endoscopic sphincterotomy prior to laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the treatment of cholelithiasis. Surg Endosc 17:872–875

Allen NL, Leeth RR, Finan KR, Tishler DS, Vickers SM, Wilcox CM, Hawn MT (2006) Outcomes of cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg 10:292–296

Berggren U, Gordh T, Grama D, Haglund U, Rastad J, Arvidsson D (1994) Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy: hospitalization, sick leave, analgesia, and trauma responses. Br J Surg 81:1362–1365

Dirksen CD, Schmitz RF, Hans KM, Nieman FH, Hoogenboom LJ, Go PM (2001) Ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy is as effective as hospitalization and from a social perspective less expensive: a randomized study. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 145:2434–2439

Hasukic S, Mesic D, Dizdarevic E, Keser D, Hadziselimovic S, Bazardzanovic M (2002) Pulmonary function after laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 16:163–165

Hendolin HI, Paakonen ME, Alhava EM, Tarvainen R, Kemppinen T, Lahtinen P (2000) Laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy: a prospective randomised trial to compare postoperative pain, pulmonary function, and stress response. Eur J Surg 166:394–399

Neugebauer E, Troidl H, Spangenberger W, Dietrich A, Lefering R (1991) Conventional versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the randomized controlled trial. Cholecystectomy Study Group. Br J Surg 78:150–154

Knight JS, Mercer SJ, Somers SS, Walters AM, Sadek SA, Toh SK (2004) Timing of urgent laparoscopic cholecystectomy does not influence conversion rate. Br J Surg 91:601–604

Jones K, DeCamp BS, Mangram AJ, Dunn EL (2005) Laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy minimally prolongs hospitalization. Am J Surg 190:879–881

McMahon AJ, Russell IT, Ramsay G, Sunderland G, Baxter JN, Anderson JR, Galloway D, O’Dwyer PJ (1994) Laparoscopic and minilaparotomy cholecystectomy: a randomized trial comparing postoperative pain and pulmonary function. Surgery 115:533–539

Ros A, Gustafsson L, Krook H, Nordgren CE, Thorell A, Wallin G, Nilsson E (2001) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus minilaparotomy cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized, single-blind study. Ann Surg 234:741–749

Barkun JS, Barkun AN, Sampalis JS, Fried G, Taylor B, Wexler MJ, Goresky CA, Meakins JL (1992) Randomised controlled trial of laparoscopic versus mini cholecystectomy. The McGill Gallstone Treatment Group. Lancet 340:1116–1119

Sand J, Airo I, Hiltunen KM, Mattila J, Nordback I (1992) Changes in biliary bacteria after endoscopic cholangiography and sphincterotomy. Am Surg 58:324–328

Sarli L, Iusco D, Sgobba G, Roncoroni L (2002) Gallstone cholangitis: a 10-year experience of combined endoscopic and laparoscopic treatment. Surg Endosc 16:975–980

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The abstract of this work was presented at the Society of American Gastroendoscopic Suregons (SAGES) 2007 annual meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schiphorst, A.H.W., Besselink, M.G.H., Boerma, D. et al. Timing of cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc 22, 2046–2050 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-9764-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-9764-8