Abstract

Purpose

Colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) is the most common surgical procedure for slow transit constipation (STC). A hemicolectomy has been suggested as an alternative to IRA with good short-term results. However, long-term results are unknown. The aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term results after hemicolectomy as a treatment for STC.

Methods

Fifty patients with STC were selected for right- or left-sided hemicolectomy after evaluation with colonic scintigraphy from 1993 to 2008. Living patients (n = 43) received a bowel function questionnaire and a questionnaire about patient-reported outcome.

Results

After a median follow-up of 19.8 years, 13 patients had undergone rescue surgery (n = 12) or used irrigation (n = 1) and were classified as failures. In all, 30 were evaluable for functional outcome and questionnaire data for 19 patients (due to 11 non-responding) could be analysed. Two reported deterioration after several years and were also classified as failures. Median stool frequency remained increased from 1 per week at baseline to 5 per week at long-term follow-up (p = 0.001). Preoperatively, all patients used laxatives, whereas 12 managed without laxatives at long-term follow-up (p = 0.002). There was some reduction in other constipation symptoms but not statically significant. In the patients’ global assessment, 10 stated a very good result, seven a good result and two a poor result.

Conclusions

Hemicolectomy for STC increases stool frequency and reduces laxative use. Long-term success rate could range between 17/50 (34%) and 35/50 (70%) depending on outcome among non-responders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The clinical presentation of slow transit constipation (STC) is heterogeneous and includes a range of symptoms like abdominal pain, hard stools and bloating [1, 2]. Laxatives, enemas and pharmaceuticals like prucalopride and linaclotide are first-line treatment [3] but in case of failure, surgery might be considered with colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) as a standard procedure [4].

Colectomy with IRA is associated with side effects such as diarrhoea, incontinence and an increased risk of small bowel obstruction (SBO) [5]. The right colon and most of the transverse colon have their parasympathetic nerve supply from the vagal nerve, whereas the left colon is innervated from the sacral nerve roots. The idea of a limited resection (e.g., hemicolectomy) is supported by the finding that some patients have a segmental defect in the colonic innervation [6]. This knowledge led to a previous study in our department where right- or left-sided colonic delay was identified with scintigraphy and thus determined the segment for resection in patients with STC [7, 8]. The short- and medium-term results after hemicolectomy were promising, with a comparable symptomatic relief compared with that after ileorectal anastomosis and possibly less severe side-effects, which could make it a better alternative for selected patients with STC [9]. However, long-term outcome has not been evaluated.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term results after hemicolectomy as a treatment for STC.

Patients and methods

The inclusion criteria were as follows: severe chronic constipation with a clinical suspicion of STC, unsuccessful conservative treatment (dietary change, fibre supplements, laxatives and biofeedback when indicated), radiographically prolonged colonic transit time and a segmental delay on colonic scintigraphy [7]. Patients that met the criteria and had a colonic resection for STC during the period 1993–2008 were included. Exclusion criteria were as follows: symptom duration less than 6 months, colonic stricture and total colonic inertia necessitating total colectomy. In total, 50 consecutive patients (47 females) were included. Patients were investigated with gastrointestinal transit time [10], video defecography, anorectal manometry and electromyography of the pelvic floor. Totally, 47 patients had predominantly left-, and three had a right-sided delay whereas the other colonic segment showed a normal or near normal transit. This definition of segmental delay on colonic scintigraphy was consistent since the method was set up in 1991 [8]. Colonic scintigraphy scans are presented in Fig. 1, showing activity in the left colon even after 8 days.

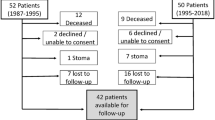

At follow-up, seven patients were deceased, leaving 43 possible for evaluation of functional outcome (Fig. 2). The medical records, the questionnaire that all patients with functional disorders completed before their visit to the outpatient clinic [11], and all the relevant postoperative history were reviewed. Surgery resulting in an increase in bowel movements accompanied by resolution of constipation symptoms without the need of reoperation because of constipation was considered successful. Failure was defined as reoperation because of constipation (colonic resection or a colostomy), need for chronic irrigation procedures or failure to increase bowel frequency at follow-up. Patients lost to follow-up and non-responders were analysed with respect to demographic variables and baseline questionnaire data (Table 1).

All patients were contacted by post and received information about the study, a consent form and two questionnaires: first, the same bowel function questionnaire used at baseline [11] and, second, a questionnaire concerning the patient-reported outcome. Non-responders received a reminder 3 months later. Faecal incontinence was evaluated by the bowel function questionnaire or through the medical records both at baseline and at follow-up. The Institutional Review Board in Uppsala County approved the study (nr 2015/270).

Surgical procedure

Among the 43 living patients, 41 underwent left-sided hemicolectomy and two a right-sided hemicolectomy. The resection was guided by the parasympathetic nerve supply to the colon. Thus, the anastomosis in the left hemicolectomies was made between the mid-transverse colon and the rectosigmoid junction, while, in right hemicolectomy, between the distal ileum and the distal transverse colon.

Statistical methods

The results are presented as median and (range). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A non-parametric test, i.e., Mann-Whitney U test or Wilcoxon matched pair test, as appropriate, was used to analyse numerical data. McNemar’s test or Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate dichotomous paired and unpaired variables. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical results

Of the 43 living patients, 13 were considered failures, based upon data from medical records: five patients were reoperated with resection of the remaining colon and received an IRA, seven patients were reoperated with stoma formation and one patient was using irrigation for constipation, leaving 30 patients for evaluation of functional outcome after segmental resection for STC (Fig. 2).

In the total cohort, there were 47 women and 3 men and the median age was 52 years (range 32–73). The median weekly stool frequency was 2 (range 0–10), and the median transit time on radiography was 5.9 (range 1.1–10). No differences were observed in age, gender, duration of symptoms or transit time between patients with a successful outcome and patients with failure (Table 1). Pathology reports could be retrieved for 32 of the patients (missing 10 from success patients and one from failures). Routine histopathologic examination showed visceral myopathy and one degenerative neuropathy among failures. In the success group, two muscular hypertrophies were observed. All other colonic specimens were described as normal. None of the patients had an ongoing medical treatment for constipation with linaclotide or prucalopride. The median follow-up time was 19.8 years (range 12.1–21.9). Concerning the seven deaths, none was related to the initial operation for STC or to constipation itself. Two patients in the failure group were reoperated for adhesive SBO and one for incisional hernia and adhesive SBO.

Functional outcome

A total of 19 patients out of 30 (63%) responded to the questionnaire. Ten reported that their constipation was resolved after surgery, while eight reported a marked improvement in symptoms. All these patients would recommend the operation to a relative, and they claimed willingness to go through the same operation again if needed. One patient reported return to his preoperative status despite the operation. He would not recommend the procedure to others, nor would he choose to undergo the same operation again. One more patient reported, despite the initial good result, decreased number of bowel movement compared with his preoperative status. He reported that his problem was partially solved as laxatives had good effect. These two patients were therefore classified as failures.

A large shift concerning stool frequency was observed after the procedure. The change in stool frequency for individual patients is shown in Fig. 3.

The use of laxatives decreased after the operation, both for each separate medication and for the combination of two or more. Preoperatively, there was no patient without the need of laxatives, while 12 managed without laxatives after the procedure (p = 0.002, Table 2). Furthermore, the use of enemas and fibre bulking agents decreased after the procedure (p = 0.004–0.001) and stool frequency changed from a median of 1 (0–10) to a median of 5 (2–16) per week (p < 0.0001, Table 3).

A numerical reduction of other symptoms was observed (painful defecation, bloating, straining and soiling), but these changes were not statistically significant (Table 3). None of the 17 patients complained of incontinence of solid stools, two reported occasional incontinence of fluids during the follow-up period and one patient reported fluid incontinence once a week. Incontinence of gas was reported more common, with three patients mentioning such a problem daily, while three more had occasional involuntary gas passage during the follow-up period. All these patients had similar symptoms before the operation, and no de novo incontinence was reported after the operation.

Discussion and conclusions

The present study shows that long-term results after hemicolectomy for slow transit constipation are fair with a successful outcome in approximately half of the patients. Patients followed up reported increased bowel frequency and reduced use of laxatives. We believe that our results support the continued use of hemicolectomy in selected patients based on radiography and scintigraphic evidence of segmental delay.

The pathogenic mechanisms for STC have been discussed. Several studies have suggested that propagating motor contractions are deficient in STC [12,13,14,15] and medical treatment usually aims at increasing intestinal secretion or stimulating and restoring motor function. Inflammatory and degenerative changes in myenteric ganglia as well as altered levels of enteric neurotransmitters have been discussed in the pathophysiology of STC [14]. In our study, the pathology reports of specimen did not allow any further analysis of possible mechanisms. Other treatment options than laxatives and enemas have been tried. Biofeedback has also produced good results in functional defecation disorders, but not in STC. [16] Sacral nerve stimulation was also tried in an RCT setting for patients with STC but showed disappointing results both in short- and long-term follow-up [17, 18]. However, in paediatric population with STC, there has been some effect of transabdominal electrical stimulation which lasted for at least 2 years [19].

As drug therapies and other treatments might have limited effect on STC, some patients require surgical interventions. Subtotal colectomy with IRA is the most widely used operation [4, 20,21,22]. A slight modification is to preserve the sigmoid colon and make an ileosigmoid anastomosis or the ileocecal valve and make a colorectal anastomosis. When these procedures were compared, those undergoing ileosigmoid anastomosis had somewhat better results [23]. Because of the irreversible nature and side effects after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis, segmental resection has been proposed. De Graff et al. [24] and Lundin et al. [9] showed that segmental colectomy had less side effects than subtotal colectomy and concluded that segmental colonic resection is a good surgical option for some patients with STC and may be superior to subtotal colectomy. We believe that a segmental resection has clinical advantages compared with a colectomy. It is a smaller procedure leaving fewer areas for adhesion and theoretically reduced risk for intestinal obstruction. Knowles et al. [25] recently presented a review showing a 15% incidence of small bowel obstruction after colectomy for constipation, with many patients requiring surgical intervention for their bowel obstruction. In addition, the tendency for diarrhoea, fluid loss and incontinence could be reduced. This view was corroborated in our study where no patients reported de novo incontinence or worsening of pre-existing leakage for solid or liquid faeces after the operation. Finally, a hemicolectomy leaves the patient with the opportunity for a later rescue colectomy.

From the available data, we could recognise 13 failures and two who returned to their previous status thus resulting in a total failure rate of 15/43 (35%). On the other hand, we identified 17 who were satisfied. When the total cohort of 50 subjects is considered, the success rate ranges from 34 to 70% depending on the assumed success rate among non-responders. This result agrees with previous studies after colectomy and IRA, [4, 21, 22, 25] although conflicting data on the results of surgical treatment for STC have been reported [4, 25, 26]. Lundin et al. reported a higher success rate (82%) at the short-term follow-up, which was partly based on the same cohort [9]. The death rate in this cohort was 14%, which is in accordance with the population statistics in Sweden, as presented by the database of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

All patients of our study group would recommend the operation to a relative and they would go through the same operation again if needed, which is comparable with reports after colectomy [26, 27]. The number of laxatives used was reduced, which also indicates a positive outcome of the treatment.

We recognise the relatively low response rate and attrition bias as a limitation, but still, the percentage of patients we could follow up on is of reasonable size and comparable with other reports in the literature.

Our study suggests that long-term clinical and functional outcome after segmental resection for STC is acceptable and most of the patients express satisfaction even after a long-term follow-up, avoiding the risk of morbidity after colectomy [26, 27].

References

American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task F (2005) An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 100:S1–S4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_1.x

Bassotti G, Chistolini F, Nzepa FS, Morelli A (2003) Colonic propulsive impairment in intractable slow-transit constipation. Arch Surg 138:1302–1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1302

Thayalasekeran S, Ali H, Tsai HH (2013) Novel therapies for constipation. World J Gastroenterol 19:8247–8251. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8247

Pinedo G, Aj Z, Garcia E, Molina ME, Lopez F, Zuniga A (2009) Laparoscopic total colectomy for colonic inertia: surgical and functional results. Surg Endosc 23:62–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-9901-4

Reshef A, Gurland B, Zutshi M, Kiran RP, Hull T (2013) Colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis has a worse 30-day outcome when performed for colonic inertia than for a neoplastic indication. Color Dis 15:481–486

Giorgio V, Borrelli O, Smith VV, Rampling D, Köglmeier J, Shah N, Thapar N, Curry J, Lindley KJ (2013) High-resolution colonic manometry accurately predicts colonic neuromuscular pathological phenotype in pediatric slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 25(1):70–8.e8-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12016

Lundin E, Karlbom U, Westlin JE, Kairemo K, Jung B, Husin S, Pahlman L, Graf W (2004) Scintigraphic assessment of slow transit constipation with special reference to right- or left-sided colonic delay. Color Dis 6:499–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00694.x

Lundin E, Graf W, Garske U, Nilsson S, Maripuu E, Karlbom U (2007) Segmental colonic transit studies: comparison of a radiological and a scintigraphic method. Color Dis 9:344–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01153.x

Lundin E, Karlbom U, Påhlman L, Graf W (2002) Outcome of segmental colonic resection for slow-transit constipation. Br J Surg 89:1270–1274. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02213.x

Abrahamsson H, Antov S, Bosaeus I (1988) Gastrointestinal and colonic segmental transit time evaluated by a single abdominal x-ray in healthy subjects and constipated patients. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 152:72–80

Osterberg A, Graf W, Karlbom U, Påhlman L (1996) Evaluation of a questionnaire in the assessment of patients with faecal incontinence and constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol 31:575–580

Singh S, Heady S, Coss-Adame E, Rao SS (2013) Clinical utlity of colonic manometry in slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 25:487–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12092

Dinning PG, Wiklendt L, Maslen L, Patton V, Lewis H, Arkwright JW, Wattchow DA, Lubowski DZ, Costa M, Bampton PA (2015) Colonic motor abnormalities in slow transit constipation defined by high resolution, fibre-optic manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil 27:379–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12502

Dinning PG, Sia TC, Kumar R, Mohd Rosli R, Kyloh M, Wattchow DA, Wiklendt L, Brookes SJH, Costa M, Spencer NJ (2016) High-resolution colonic motility recordings in vivo compared with ex vivo recordings after colectomy, in patients with slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 28:1824–1835. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12884

Andromanakos NP, Pinis SI, Kostakis AI (2015) Chronic severe constipation: current pathophysiological aspects, new diagnostic approaches and therapeutic options. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27:204–214. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000288

Chiarioni G (2016) Biofeedback treatment of chronic constipation: myths and misconceptions. Tech Coloproctol 20:611–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-016-1507-6

Dinning PG, Hunt L, Patton V, Zhang T, Szczesniak M, Gebski V, Jones M, Stewart P, Lubowski DZ, Cook IJ (2015) Treatment efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation in slow transit constipation: a two-phase, double blind randomized controlled crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol 110:733–740. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.101

Patton V, Stewart P, Lubowski AZ, Cook IJ, Dinning PG (2016) Sacral nerve stimulation fails to offer long-term benefit in patients with slow-transit constipation. Dis Colon Rectum 59:878–885. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000653

Hutson JM, Dughetti L, Stathopoulos L, Southwell BR (2015) Transabdominal electrical stimulation (TES) for the treatment of slow-transit constipation (STC). Pediatr Surg Int 31:445–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-015-3681-4

Suares NC, Ford AC (2011) Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 106:1582–1591. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.164

Athanasakis H, Tsiaoussis J, Vassilakis JS, Xynos E (2001) Laparoscopically assisted subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation. Surg Endosc 15:1090–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004640090046

Thaler K, Dinnewitzer A, Oberwalder M, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Efron J, Vernava AM III, Wexner SD (2005) Quality of life after colectomy for colonic inertia. Tech Coloproctol 9:133–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-005-0211-8

Feng Y, Jianjiang L (2008) Functional outcomes of two types of subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation: ileosigmoidal anastomosis and cecorectal anastomosis. Am J Surg Jan 195(1):73–77

de Graaf EJR, Gilberts ECAM, Schouten WR (1996) Role of segmental colonic transit time studies to select patients with slow transit constipation for partial left-sided or subtotal colectomy. Br J Surg 83:648–651

Knowles CH, Grossi U, Chapman M, Mason J, NIHR CapaCiTY working group, Pelvic floor Society (2017) Surgery for constipation: systematic review and practicerecommendations. Results I: Colonic resection. Color Dis 19:17–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13779

Ripetti V, Caputo D, Greco S, Alloni R, Coppola R (2006) Is total colectomy the right choice in intractable slow-transit constipation? Surgery 140:435–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2006.02.009

Hassan I, Pemberton JH, Young-Fadok TM et al (2006) Ileorectal anastomosis for slow transit constipation: long/term functional and quality of life results. J Gastrointest Surg 10:1330–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gassur.2006.09.006

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study and the data collection. KT, WG and UK contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All patients were contacted by post and received information about the study, a consent form and two questionnaires. The Institutional Review Board in Uppsala County approved the study (nr 2015/270).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsimogiannis, K.E., Karlbom, U., Lundin, E. et al. Long-term outcome after segmental colonic resection for slow transit constipation. Int J Colorectal Dis 34, 1013–1019 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03283-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03283-5