Abstract

Objectives

To assess the costs of diagnostic workup and surgery of three strategies for patients with colorectal cancer liver-metastases (CRCLM): gadoxetic-acid-enhanced MRI (Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI), MRI with extracellular contrast-media (ECCM-MRI) or contrast-enhanced MDCT (CE-MDCT).

Methods

The within-trial cost evaluation was modelled as a decision-tree to calculate the cost of diagnosis and surgery. The model used clinical outcomes and resource utilization data from a prospective randomized multicentre study. Analyses were performed for the 354-patient safety population from eight participating countries.

Results

The diagnostic workup cost using Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI upfront resulted in savings compared to ECCM-MRI in all countries except Thailand (difference <2 %). Compared to CE-MDCT, initial imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI was less costly in all countries except Korea and Spain (differences 4 and 8 %, respectively). Significantly more patients in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group were eligible for surgery (39.3 % (48/122) vs. 31.0 % (36/116) and 26.7 % (31/116) for ECCM-MRI and CE-MDCT, respectively), allowing more patients to undergo potentially curative surgery, but resulting in higher treatment costs for the strategy starting with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI.

Conclusions

The benefits of Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI due to less additional imaging and similar diagnostic workup costs in the three groups suggest that Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI should be the preferred initial imaging procedure to evaluate hepatic resectability in patients with CRCLM.

Key Points

• Diagnostic imaging cost to evaluate resectability was similar among the groups

• Cost for imaging was rather small compared to the cost of surgery

• Significantly more patients in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI arm were eligible for surgery

• Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI is recommended for evaluating hepatic resectability in patients with CRCLM

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the leading causes of tumour-associated deaths [1]. A major determinant of outcome is the extent of disease. Patients with metastatic (Stage IV) disease have a 5-year survival rate of 12 % compared with 90 % for Stage I/II and 70 % for Stage III disease [2]. Twenty-five to 50 % of patients with CRC present with liver metastases, either synchronous or metachronous (at a later stage), after the initial diagnosis of the primary tumour [3]. Surgery can achieve cure in both hepatic and extrahepatic metastatic disease, provided that all of the tumour can be resected. Overall 5-year survival ranges between 16 % and 74 % after liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastasis [4]. Hepatic recurrence can be expected in 50–60 % of patients with hepatic metastases [5–7].

Surgical strategy in patients scheduled for liver resection is based on pre-operative imaging with a variety of modalities, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound (US) and positron emission tomography (PET) or PET-CT. The final assessment of the extent of the disease, however, is made during the operation by surgical exploration of the liver and intra-operative ultrasound. Deviation from the pre-operative surgical plan due to additional intra-operative findings is undesirable and can potentially lead to increased costs.

MRI has been demonstrated to be the best imaging method for detection and characterization of focal liver lesions [8–10]. The detection and characterization capabilities of MRI can be enhanced further by using hepatobiliary contrast agents like gadoxetic-acid (gadolinium ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine-penta-acetate; Gd-EOB-DTPA) [11–18]. The VALUE study, a prospective, randomized trial that compared Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI, MRI with extracellular contrast media (ECCM-MRI) and contrast-enhanced multiple detector CT (CE-MDCT) for hepatic staging of patients with suspected or confirmed metachronous CRC-liver metastases (CRCLM), has recently been published [19]. The VALUE study showed that patients randomized to initial diagnostic imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI needed significantly fewer additional imaging procedures for a confident diagnosis and treatment decision, compared to those randomized to ECCM-MRI or CE-MDCT as initial imaging modality. Furthermore, Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI imaging yielded a significantly higher confidence in the diagnosis and treatment plan compared to the other two modalities. The information provided by Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI resulted in a decreased number of patients with intra-operative modifications of the surgical plan in patients undergoing liver resection.

The economic implications of the medical benefits of initial imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI observed for patients in this clinical scenario, however, remain to be determined. Thus, the purpose of this within-trial cost evaluation of the VALUE study was to assess the comparative costs of diagnostic workup and surgery of the three strategies; i.e. initial imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI, ECCM-MRI or CE-MDCT in patients with suspected CRCLM.

Materials and methods

This within-trial cost evaluation of the VALUE study was based on data for 360 patients with known or suspected metachronous liver metastases secondary to colorectal cancer who were scheduled for further contrast-enhanced tomographic imaging, who were randomized to one of the three initial imaging techniques. The randomization list was developed by a biometrician. The final randomization code was generated using the validated program RANDOM as 1 : 1 : 1 randomization (block size 6). The randomization list included the randomization codes, patient identifier and assigned imaging modality. The randomization information was provided in sealed envelopes that were kept securely in the radiology department at each study site. Patients were recruited from eight countries (Switzerland N = 3; Sweden N = 4; Italy N = 13; Spain N = 16; Thailand N = 62; Austria N = 77, Germany N = 83 and Korea N = 102). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, following approval by relevant ethics committees/institutional review boards at the participating centres. All patients gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Six patients did not receive any treatment or contrast agent in the study and were dropouts (screening failures). All patients who received any amount of contrast medium were included in the safety population (N = 354). Population characteristics as well as safety analyses were performed using all available data from those patients. All patients who received a contrast medium, for whom the primary parameter was available and who had no major protocol deviation, were included in the efficacy population (N = 342).

Whenever possible, the analyses in this manuscript were made on the safety population. Some data presented in this paper differ slightly from those in the article describing the clinical results of the VALUE study [19], where most of the analyses were performed on the efficacy population.

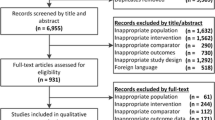

The safety population was as follows: 122 had initial imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI, 116 with ECCM-MRI and 116 with CE-MDCT. For some homogeneity analyses, however, the efficacy population consisting of 342 patients was used since some of the variables tested were only measured for those patients who completed the study. This trial-based cost analysis was programmed as a decision-tree (using TreeAge Pro 2009), designed to mirror the outline of a model-based health-economic approach published previously [20] and populated with actual clinical data from the VALUE study [19]. An overview of the decision tree is given in Fig. 1.

Transition probabilities

After the initial imaging procedure, the first consensus meeting consisting of the local investigators (liver surgeon and radiologist, and in some instances also an oncologist according to local practice) was held to decide whether a confident treatment decision could be made or if further imaging was required to come to a therapy decision. The consensus group was aware of the intent of the study and that a health-economic evaluation was planned after publishing the primary study results. If further imaging was required, the interdisciplinary team (as specified above) was free to choose one of the two remaining imaging modalities, followed by another interdisciplinary team meeting. After pre-treatment imaging (one or two modalities), a treatment plan was drafted with patients with potentially operable disease being referred for surgical intervention. In patients deemed operable, a detailed operation plan was drafted. The probabilities for ‘further imaging required’ were calculated from the patient-level data as the proportion of patients who required a second imaging procedure (Table 1).

In total, 115 patients were assessed as being primarily resectable, i.e. could be rendered tumour free by one operative intervention (surgery with/without concomitant local ablation) without the necessity of pre-operative tumour or volume manipulation by down-staging chemotherapy or portal-vein embolization. During surgery, it was documented whether the operation resulted in liver resection and whether the pre-operative surgical plan was executed unchanged or modified due to additional intra-operative findings. Among patients for whom the surgical plan was modified during surgery, the probability of having a longer intervention was estimated and the difference in surgery time due to modification of the surgical plan was recorded. The difference in surgery time was intended to judge the estimated amount of additional planning time, and not the increase in the procedural time itself.

Finally, the probabilities of modification of the surgical plan resulting in no resection during surgery (i.e. undergoing non-therapeutic intervention, hereafter referred to as ‘unnecessary surgery’) were estimated from the patient-level VALUE data. These transition probabilities are presented in Table 2. Transition probabilities and resource use were always estimated for the pooled patient population, and not stratified by country. As such, the sample size was the same for all countries, so that the differences in patients included per country did not have an effect on the country-specific evaluation later on.

Resource utilization and cost

A payer perspective was adopted for the cost analysis with Germany as the base case. Analyses were then conducted for the remaining countries participating in the trial: Austria, Italy, Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Thailand. Unit costs collected for these countries were multiplied by the resource utilization of the pooled population for a cross-country comparison (unit costs and references are presented in Supplemental Table 1).

The VALUE data contained the following detailed patient-level information on resource utilization: (a) contrast agents used for the imaging, (b) length of surgery, (c) estimated additional length of surgery in case of a modified surgical plan, (d) number of days of intensive care following surgery and (e) number of days of standard in-hospital care following surgery.

The total cost of diagnostic workup in each group was calculated as: [cost of imaging procedure without contrast + cost of contrast media expressed as the weighted average of substances used in the VALUE trial + cost of a consensus meeting(s)]. The list of contrast agents, their weights and costs are presented in Supplemental Table 1. The cost of the consensus meeting was estimated in consultation with clinical experts in each country, following local practices. In some countries, it consisted of a surgeon and radiologist while in others an oncologist was also involved (Supplemental Table 2). The aim of this approach was to obtain cost estimates mirroring the VALUE trial that would be applicable to each country’s clinical routines.

The cost of planned surgery was calculated as: [surgery time*cost per minute of surgery under anaesthesia + days in intensive care*cost per day in intensive care + days in standard care*cost per day in standard care]. The additional cost of prolonged surgery was calculated as: [mean additional length of surgery *cost per minute of surgery under anaesthesia]. The resource use (minutes of surgery and days in hospital) was calculated as the total means across all imaging sequences. The resource use was calculated separately for resected and unresected patients (Table 3), based on the assumption that the length of surgery and the days spent in hospital would be different for patients with surgery but without any resection and those with surgery and liver metastases resection.

Statistical analysis

Homogeneity chi-square tests were performed to test for randomization bias with regard to age and disease severity as measured by (a) presence of non-assessable lesions, (b) presence of assessable lesions, (c) number of affected segments, and (d) total number of lesions. Following cost estimation, one-way sensitivity analyses were performed by systematically varying one input value at a time (values [prices and probabilities] were varied by ±5 %) and observing the impact of that change on the results. Sensitivity analyses were performed on the base case, i.e. using 2013 German unit costs. In addition, three alternate scenarios were included.

The first alternative scenario was ‘No avoided surgery due to missing additional information of second imaging in the CE-MDCT group’. This scenario was chosen based on five patients in the CE-MDCT group, for whom unnecessary surgery was avoided as the result of a secondary imaging (four cases with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group and one case with ECCM-MRI). The second scenario was ‘Unresectable patients recognized before surgery’. In this scenario, two patients who were unresectable because of extrahepatic disease burden were assumed to have been classified as unresectable from the beginning (a second advanced primary tumour of the sigmoid colon in a patient in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group and extrahepatic growth and peritoneal metastases in a patient in the ECCM-MRI group). In the third scenario, it was assumed that the probability for selection for surgery was equal in all three groups (32.5 %; representative of the 115 patients out of 354 in the whole dataset who were selected for surgery). This third scenario corrects for the impact of more patients being selected for surgery in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group relative to the other two groups.

All statistical analyses were done in Stata version 10.0.

Results

Homogeneity analysis

The imaging strategy starting with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI detected CRCLM in significantly more patients compared to ECCM-MRI or CE-MDCT (85/118 (70.0 %), 72/112 (64.3 %) and 66/112 (58.9 %), respectively [P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test (pairwise)]). Moreover, more patients diagnosed with liver metastases in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group were assessed as eligible for surgery (39.3 % (48/122) vs. 31 % (36/116) and 26.7 % (31/116) in the ECCM-MRI and CE-MDCT groups, respectively). The results of the homogeneity analysis are presented in Supplemental Table 3: randomization bias between the groups with regard to patients’ age or disease severity as measured by the different proxies evaluated could be ruled out between the three groups.

Cost of diagnostic workup

Costs for diagnostic workup and surgery for the three strategies are summarized in Table 4 and Fig. 2. Initial imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI resulted in cost savings compared to ECCM-MRI in all countries except Thailand where the difference was less than 2 %. Compared to CE-MDCT, initial imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI was less costly in all countries, except Korea and Spain, where the differences were 4 % and 8 %, respectively. These results are explained by the significant difference in the need for additional imaging procedures (Fig. 3).

Cost of surgery

The results of the additional cost of surgery associated with the three imaging strategies are also presented in Table 4. In addition to the cost of the planned surgical procedure, the consequences of each diagnostic strategy regarding surgery were measured by two secondary outcomes: the costs accrued by intra-operative modification of pre-operative surgical plans and the costs of surgery where no resection was performed (unnecessary surgery). The additional length of surgery due to a modified surgical plan ranged from 20–120 min (median 45 min; mean 49 min). No resection was performed in three patients who underwent surgery.

The cost of surgery was higher in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group (as significantly more patients underwent surgery), resulting in higher total costs accrued by these patients as a group. However, when the cost consequences (excluding the cost of the planned surgery) were evaluated, initial imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI was less expensive than the strategy starting with ECCM-MRI across all countries, but was more expensive than starting with CE-MDCT across all countries, except Sweden where starting with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI was the least costly alternative (Table 4).

Sensitivity analysis and alternative scenarios

The results of the one-way sensitivity analysis and of three alternative scenarios are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Sensitivity analysis showed that the cost of liver surgery for resected patients was the main driver for total cost. In the first alternative scenario (‘No avoided surgery due to missing additional information of second imaging in the CE-MDCT group’), if patients with missing information had not undergone the second imaging and instead had unnecessary surgery, they would have generated costs as depicted in Table 5. While the total costs are still higher in the strategy starting with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI than starting with CE-MDCT, the difference decreased from €1,036 to €465 per patient. In the second scenario (‘Unresectable patients recognized before surgery’), the total cost difference between Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI and ECCM-MRI remained almost unchanged, whereas the difference between Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI and CE-MDCT decreased by approximately 6 %. In the third scenario (‘Assumed that the probability for selection for surgery was equal in all three groups’), the total cost differences between all three strategies were negligible.

Discussion

This study analysed the cost impact of three different imaging strategies (Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI, ECCM-MRI, CE-MDCT) in the evaluation of patients with confirmed or suspected CRCLM. In almost all scenarios, the cost of diagnostic workup was lower when Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI was used as the initial imaging procedure compared with other strategies, despite it being the more expensive imaging modality compared with ECCM-MRI and CE-MDCT. This was due to the fact that no patient in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group required additional imaging for a treatment decision, compared to 18.1 % and 39.7 % of the safety population in the ECCM-MRI and CE-MDCT groups, respectively.

Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI as the initial imaging procedure resulted in the detection of CRCLM in significantly more patients, offering more patients a more definitive assessment and, in suitable candidates, potential curative treatment. This result is in line with previous studies, which demonstrated the superior sensitivity of Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI to detect liver metastasis [12–14, 21–23]. The observation that a higher percentage of patients in the group where Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI was the initial imaging procedure were assessed as eligible for surgery, compared to the other two groups, was particularly interesting. A possible explanation could be that the higher confidence in the pre-operative imaging stimulated bolder treatment decisions, especially regarding more aggressive surgical approaches. Methodologically we can rule out a bias due to the centrally organized randomization procedure as described in the methods part as well as an improper randomization with regard to patients mean age, presence of non-assessable lesions, number of affected segments, and total number of lesions (Supplemental Table 3). Any unknown bias, however, cannot be ruled out completely. Moreover, the decisions regarding eligibility for surgery were made locally in the centres and thus influenced by the local expertise.

Cost calculations must be considered in the context of the relevant endpoints and interpreted with reference to the ultimate goals of imaging in patients with CRCLM: sensitive detection, accurate staging and correctly identifying patients that can be offered potentially curative intervention. Interestingly enough, the main driver of cost in our study was not cost of imaging or contrast media, but cost of surgery. As more patients in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group underwent surgery, the total cost of surgery was higher in this group. This fact should not be interpreted in the sense that Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI generates higher health-care costs, but that it better fulfils the ultimate goals of imaging as mentioned above. Even if patients cannot be operated on directly, but can be resected only after a downsizing pre-operative chemotherapy, the detailed knowledge of the initial findings seems to be of high relevance to prevent local hepatic recurrences [21, 23].

The calculations were undertaken for several countries with varied health-care systems and different levels of health resources and spending, including resource-challenged countries, lending strength to the results. Furthermore, rather than using protocol-defined clinical routines, regional differences in the compilation of multidisciplinary treatment conference teams were accounted for, making the findings more robust in terms of real-life clinical practice. Although there were huge differences in the reimbursement systems and unit costs, the general outcome in the different countries was quite uniform.

From a patient perspective, the eligibility for surgery for liver metastases represents a favourable event, changing often from an initially assumed incurable situation to a potentially curable situation, associated with a good chance of long-term survival. From a hospital perspective, with reimbursement systems in place in most countries, the higher costs are likely to be covered by the higher revenue from the medical procedures undertaken. Furthermore, from a health-care provider perspective, the costs need to be weighed against the mid- and long-term clinical and economic benefits of the potentially life-preserving surgery. Potential advantages in the management of surgical candidates may even increase the economic benefit of a strategy starting with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI, as the need for an additional imaging procedure after initial unequivocal imaging findings may defer some treatments.

The results of this study are consistent with results from a previously published health economic model that was designed to estimate the aggregated costs of three different imaging strategies in patients with metachronous CRCLM [20]. In that study, data collected from a Delphi panel composed of 13 pairs of clinical experts using a decision-tree model, estimated probabilities for the need of further imaging to come to a treatment decision. Applying actual clinical data to the model from diverse clinical practices due to the multinational nature of the VALUE trial, the performance of Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI was better in the clinical trial than predicted in the health economic model (actual need for further imaging 0 % compared to 8.6 % in the model). Specifically, the prediction that fewer examinations may lead to cost savings in the strategy starting with Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI has been confirmed by the clinical study data.

The main limitation of this study was the lack of follow-up of patients. The long-term clinical and economic impact of each diagnostic strategy can therefore not be estimated. The measurement of cost for the different imaging strategies go far beyond the endpoints used in this paper. The performance of the imaging is likely to affect health-care costs in patients until the time of death or confirmation of a cure. For example, in patients where curative intended treatment was initiated too late due to a delay in diagnosis related to suboptimal imaging, the cost of palliative measures has to be measured against the cost of possible curative surgery. Likewise, tumour recurrence as the result of suboptimal imaging in patients undergoing curative-intended intervention will incur costs for both surgery and palliative treatment, probably without any survival advantage. It must, however, be emphasized that the cost for individual patients in terms of suffering and premature death due to failed therapeutic strategies as a result of sub-optimal imaging is immeasurable.

In conclusion, the cost of the diagnostic work-up was similar in all three arms, despite the fact that Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI is more expensive than ECCM-MRI and CE-MDCT, due to the fact that patients randomized to Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI did not require additional imaging. The cost of surgery was higher in the Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI group, as significantly more patients underwent surgery; however, this has to be regarded in the sense that Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI better fulfils the ultimate goals of imaging to identify suitable patients for liver surgery, thereby offering them a curative approach.

References

Adam R, De Gramont A, Figueras J et al (2012) The oncosurgery approach to managing liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Oncologist 17:1225–1239

American Cancer Society 2011 Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2011–2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. Available via http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028323.pdf. Accessed 08 January 2015

Sjövall A, Järv V, Blomqvist L et al (2004) The potential for improved outcome in patients with hepatic metastases from colon cancer: a population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol 30:834–841

Kanas GP, Taylor A, Primrose JN, Langeberg WJ, Kelsh MA, Mowat FS et al (2012) Survival after liver resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Epidemiol 4:283–301

Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF et al (2002) Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg 235:759–766

Pawlik TM, Scoggins CR, Zorzi D et al (2005) Effect of surgical margin status on survival and site of recurrence after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg 241:715–722, discussion722–724

Abdalla EK, Vauthey J-N, Ellis LM et al (2004) Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg 239:818–825, discussion 825–827

Floriani I, Torri V, Rulli E et al (2010) Performance of imaging modalities in diagnosis of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging 31:19–31

Niekel MC, Bipat S, Stoker J (2010) Diagnostic imaging of colorectal liver metastases with CT, MR imaging, FDG PET, and/or FDG PET/CT: a meta-analysis of prospective studies including patients who have not previously undergone treatment. Radiology 257:674–684

Bartolotta TV, Taibbi A, Midiri M, La Grutta L, De Maria M, Lagalla R (2010) Characterisation of focal liver lesions undetermined at grey-scale US: contrast-enhanced US versus 64-row MDCT and MRI with liver-specific contrast agent. Radiol Med 115:714–731

Donati OF, Hany TF, Reiner CS et al (2010) Value of retrospective fusion of PET and MR images in detection of hepatic metastases: comparison with 18F-FDG PET/CT and Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI. J Nucl Med 51:692–699

Hammerstingl R, Huppertz A, Breuer J et al (2008) Diagnostic efficacy of gadoxetic acid (Primovist)-enhanced MRI and spiral CT for a therapeutic strategy: comparison with intraoperative and histopathologic findings in focal liver lesions. Eur Radiol 18:457–467

Huppertz A, Balzer T, Blakeborough A et al (2004) Improved detection of focal liver lesions at MR imaging: multicenter comparison of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR images with intraoperative findings. Radiology 230:266–275

Löwenthal D, Zeile M, Lim WY et al (2011) Detection and characterisation of focal liver lesions in colorectal carcinoma patients: comparison of diffusion-weighted and Gd-EOB-DTPA enhanced MR imaging. Eur Radiol 21:832–840

Muhi A, Ichikawa T, Motosugi U et al (2011) Diagnosis of colorectal hepatic metastases: comparison of contrast-enhanced CT, contrast-enhanced US, superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced MRI, and gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 34:326–335

Seo HJ, Kim M-J, Lee JD, Chung W-S, Kim Y-E (2011) Gadoxetate disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging versus contrast-enhanced 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for the detection of colorectal liver metastases. Investig Radiol 46:548–555

Merkle EM, Zech CJ, Bartolozzi C, et al. (2015) Consensus report from the 7th International Forum for Liver Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Eur Radiol

Neri E, Bali MA, Ba-Ssalamah A, et al. (2015) ESGAR consensus statement on liver MR imaging and clinical use of liver-specific contrast agents. Eur Radiol

Zech CJ, Korpraphong P, Huppertz A et al (2014) Randomized multicentre trial of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI versus conventional MRI or CT in the staging of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Br J Surg 101:613–621

Zech CJ, Grazioli L, Jonas E et al (2009) Health-economic evaluation of three imaging strategies in patients with suspected colorectal liver metastases: Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI vs. extracellular contrast media-enhanced MRI and 3-phase MDCT in Germany, Italy and Sweden. Eur Radiol 19:S753–S763

Knowles B, Welsh FKS, Chandrakumaran K, John TG, Rees M (2012) Detailed liver-specific imaging prior to pre-operative chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases reduces intra-hepatic recurrence and the need for a repeat hepatectomy. HPB 14:298–309

Sofue K, Tsurusaki M, Murakami T et al (2014) Does gadoxetic acid-enhanced 3.0T MRI in addition to 64-detector-row contrast-enhanced CT provide better diagnostic performance and change the therapeutic strategy for the preoperative evaluation of colorectal liver metastases? Eur Radiol 24:2532–2539

Yu MH, Lee JM, Hur BY et al (2015) Gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging for the detection of colorectal liver metastases after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur Radiol 25:2428–2436

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by Bayer HealthCare.

We are thankful to Karsten Bergman and the VALUE study group: Pornpim Korpraphong, Alexander Huppertz, Timm Denecke, Myeong-Jin Kim, Wiwatana Tanomkiat, Seong Hyun Kim, Young Kon Kim, Jens Ricke, Chang-Hee Lee, Renate Hammerstingl, Javier Castell Monsalve, Peter Reimer, Jeong Min Lee, Luigi Grazioli, Simone Gschwend and Susanne Baroud; as well as to the medical team at Bayer for providing useful input on unit costs: Holger Awater, Ernst Braun, Sara Cortinovis, Jessica Ihrig, Ulf Jersenius, HyunJi Shin, Jin Han, Sittipong Liamsuwan, Juergen Neumann, Kajsa Olsson and Ute Willmann.

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Christoph J. Zech. The authors of this manuscript declare relationships with the following companies: Eduard Jonas, Christoph J. Zech, Ahmed Ba-Ssalamah and Harald Rinde have received consultancy fees and honoraria for lectures from Bayer AG. Optum, employer of Nahila Justo and Andrea Lang, received consultancy fees for the economic evaluation. Nahila Justo and Andrea Lang kindly provided statistical advice for this manuscript. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study. Some study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported in Zech et al.; Br J Surg 2014; 101: 613–622. Methodology: prospective, randomised controlled trial, multicentre study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental Table 1

(DOCX 46 kb)

Supplemental Table 2

(DOCX 36 kb)

Supplemental Table 3

(DOCX 36 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zech, C.J., Justo, N., Lang, A. et al. Cost evaluation of gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of colorectal-cancer metastasis in the liver: Results from the VALUE Trial. Eur Radiol 26, 4121–4130 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4271-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4271-0