Abstract

Although Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) is the second most common metabolic bone disease, there is only limited information about the microarchitecture of affected bones. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine cortical and trabecular bone properties in clinically relevant locations by microcomputed tomography (µCT). Ten femora and ten tibiae affected by Paget’s disease taken from the Natural History Museum Vienna were compared to 13 femora and 10 tibiae of non-affected body donors. Digitization of the cortical and trabecular bone microarchitecture was performed with an X-ray-based µCT scanner. Additionally, semi-quantitative gradings of trabecular and cortical architectural parameters of the femora and the tibiae were generated. Microcomputed tomography images showed changes in the thickness of cortices, cortical porosity, and trabecularization of cortical structures. Moreover, severe disorganization of trabecular structures, trabecular defects, and thickening of (remaining) trabeculae were detected. Numerical cortical analyses showed lower total bone volume (BV) and lower BV in the outer region (66–100%) (− 36%, p = 0.004, and − 50%, p < 0.001, respectively), lower total volume (TV) in the outer region (66–100%) (− 42%, p < 0.001), lower total bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and BV/TV in the outer region (66–100%) (− 23%, and − 12%, p < 0.001, respectively), higher BV and TV in the middle region (33–66%) and higher BV/TV in the inner region (0–33%) (123%, p = 0.011, 147%, p = 0.010, and 33%, p = 0.025, respectively) in Pagetic compared to non-affected bones. Trabecular analyses showed higher BV/TV (96%, p = 0.008) and Tb.Th (43%, p = 0.004) in Pagetic compared to non-affected bones. There is a major and consistent structural alteration of PDB at cortical and trabecular sites in weight-bearing long bones. Our findings are relevant for the differential diagnosis of PDB and for the pathogenesis of associated complications, since the disorder produces abnormalities in the structure that might lead to bone fragility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Paget’s disease of bone (PDB), also known as Osteitis deformans, was originally described by Sir James Paget in 1877. His report has become a classic in the medical literature [1]. The disease is a chronic bone abnormality, which may affect a single, several, or many bones but never involves the entire skeleton. The axial skeleton is frequently involved, and the bones most commonly affected include the pelvis (70%), femur (55%), lumbar spine (53%), skull (42%), and tibia (32%) [2, 3]. Nevertheless, Pagetic bone lesions can occur at any site of the skeleton [4]. The diagnosis of PDB is rare before the age of 50. The disease affects both sexes [5], but males have been reported to show a higher frequency. Moreover, a variation in age and regional (geographical) distribution has been observed: Schmorl [6] found a prevalence of 3% of PDB in a series over 4600 autopsies of individuals above 40 years of age. The prevalence of the disease is highest in Western Europe (in particular in Britain), North America, and Australia, whereas the disease is rare in Scandinavia, Asia, and Africa [7]. Most patients are asymptomatic [8], while others develop complications such as bone pain, osteoarthritis, fracture, deformity, deafness, and nerve compression syndromes [4].

Despite the fact that PDB is the second most common metabolic bone disease [9], analyses of bone structure in Paget’s disease on a quantitative level are rare, with the exception of histomorphometric analyses of biopsies of the iliac crest [4, 10] and the spine [11]. To date, there are no histomorphometric studies based on long bones, except one case report [12] of a femur fracture associated with PDB in an Asian patient.

Over the past years—as an alternative to bone histomorphometry—non-invasive radiological imaging and quantification techniques for the study of bone microarchitecture have been developed [13,14,15]. Microcomputed tomography (µCT) produces high-resolution images of trabecular and cortical structures. However, the increasing availability of advanced imaging techniques of bone microstructure could be of hallmark importance for a better understanding of bone deformity and bone fragility in PDB. Up to now, there are no studies using µCT to investigate the microarchitecture of Pagetic long bones.

The goal of the present study was to examine the cortical and trabecular bone microstructure in historic and clinically untreated PDB cases stored at the Pathological-Anatomical Collection housed at the Natural History Museum Vienna (PASiN-NHM) [16]. Some of its specimens exhibit deformities caused by Paget’s disease according to the bequeathed hand-written documentary evidence. For comparative purposes, we also include a control group of femora and tibiae of non-affected body donors provided by the Division of Anatomy, Medical University of Vienna.

Although most µCT scanners are rather limited with regard to sample size, a few scanners, like the one we used at the Vienna Micro-CT Lab, allow the non-destructive imaging of microstructures of large bones such as femora and tibiae. This offers a unique and novel chance to extend our knowledge and to make advances in identifying the metabolism of Pagetic bone disease—even in a less progressed phase. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective systematic study based on high-resolution µCT scans concomitantly analyzing the effects of the disease on trabecular and cortical structure in long bones.

Materials and Methods

Acquisition of Pagetic and Control Bones

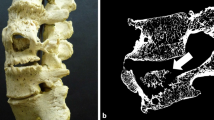

We selected dry preparations of ten femora and ten tibiae affected by Paget’s disease from the Pathological-Anatomical Collection at the Natural History Museum Vienna (most of them date to the first half of the twentieth century AD). It is important to mention that all the selected bones were macroscopically affected by the disease. We selected femora and tibiae with the clinicopathologic diagnosis of PDB. This diagnosis was macroscopically validated according to the description of Ortner and Putschar [17]. If weight-bearing long bones are concerned, the most characteristic diagnostic feature is bowing and thickening, which is a representative criterion of the late phase of the disease (early stages implied, e.g., by terminated areas of lytic resorption, are non-diagnostic). This feature is interpreted as being the consequence of “complete or incomplete transverse pathological fractures” caused by the mechanical impairment of Paget bone. On the cut surface of a dry bone, a thickening and lamination of the cortical bone, a narrowing of the medullary canal, and irregularly formed coarsened cancellous bone become visible [17]. Because of the obvious macroscopic alterations of the Pagetic bones, blinding of the observers was not possible. Since this collection does not contain healthy bones, we collected 13 femora and 10 tibiae from the Division of Anatomy, Medical University of Vienna. No abnormalities could be detected during the macroscopic inspection of bones obtained from these body donors.

The contemporary control bones were prepared in a way that resembled the conventional preparation technique used in the nineteenth century, warm water maceration at 35 °C. By this approach, possible preparation-related effects could be avoided. Preparation of bones involved bone disarticulation, soft tissue removal or bone cleaning, maceration, bone bleaching, and labeling [18]. There are a variety of methods or techniques used in bone preparation [19]. This includes maceration of dissected specimens through submersion in water for a period of time, burying in soil, as well as boiling in hot water [20].

µCT Scanning

We performed scanning of the cortical and trabecular bone microarchitecture with an X-ray based µCT scanner (Viscom X-8060-II, Vienna Micro-CT Lab, Department of Anthropology, University of Vienna) using the following scan parameters: transmission tube, digital detector, 110 kV, 380 µA, filter: 0.50 mm copper. The zoom factor was in the range between × 3.0 and × 4.3 to achieve a spatial resolution of 40 µm. Since most of the compact bone is located at the diaphysis of long bones, but the cancellous bone is located in the metaphysis, we have selected the central region of the shafts of femora and tibiae as cortical bone sites, and the proximal metaphyses for analyzing the trabecular microarchitecture of those same bones.

Our measurements, terminology, and units used for the present analyses generally followed the recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research [21].

Semi-quantitative Grading

Semi-quantitative gradings of cortical bone (i.e., thickness of cortices, porosity, and trabecularization) and trabecular bone (i.e., trabecular defects, thickness of trabeculae, visual perception of the amount of trabeculae, separation of trabeculae, and sclerosis) were performed. The scale consisted of the following four grades:

0 = within normal limits,

1/− 1 = slight alterations,

2/− 2 = moderate alterations,

3/− 3 = severe alterations.

Values refer either to an increase (+) or a decrease (−) of the parameter relative to normal (0). An expert bone researcher (EN) interpreted the qualitative grading of the µCT images and, in case of doubt, a second expert bone researcher (PP) was involved in the process.

Cortical and Trabecular Bone Microarchitecture

Since the incidence of the disease is higher in femora than in the tibiae [22, 23], we have selected the femora for further detailed investigation. Therefore, numerical analyses of bone microarchitecture in Pagetic and control femora were performed using (Fiji) [24], ImageJ [25], 1.51 h with the BoneJ [26] 1.3.11 plugin.

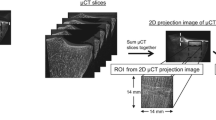

Since the exact spatial boundaries of cortical bone are very difficult to determine, the bone was measured in different density brackets to get comparable results. The following procedure was performed using Definiens Developer XD 2.1 (Definiens AG, Munich, Germany). The original µCT scans were available at an isotropic resolution of 40 µm. These images were downscaled to 50% (80 µm isovoxel). The images were then thresholded and pores inside the segmented bone were filled by dilating the bone [27] by three voxels followed by erosion of three voxels. An approximately 34 mm large region in the center of the scan was selected for measurement and adjusted for the orientation of the femur. This region was selected to maximize the area in the center of the femur while excluding artifacts present at the edge of the scans. The bone was divided into three subregions based on the local bone volume fraction (BV/TV) which ranged from 0 to 33%, 33 to 66%, and 66 to 100% (Fig. 1a). The local density was measured for each voxel as the bone volume fraction of the surrounding volume up to a distance of 800 µm. The void volume between inside the bone was assigned to density brackets using surface tension-constrained region growing. The resulting subregions were copied to the full resolution images (40 µm) and the bone was re-thresholded inside these subregions to measure the BV/TV. The subregions were then exported as image stacks. The original scans and subregions were imported into Fiji (Fiji [24] + ImageJ) [25] and the thickness of the brackets was measured using the thickness measurement implemented in the BoneJ plugin [26]. Due to the large size of the region of interest, the images were again downsized to 50% (80 µm isovoxel) of their original resolution for these thickness measurements.

Trabecular measurements in the femora were performed separately for the head and neck regions (Fig. 1b). To avoid subjectivity, the exact size and position of the region was determined automatically according to the following procedure which was performed using Definiens Developer XD 2.1 (Definiens AG, Munich, Germany). The µCT scans were taken at an isotropic resolution of 40 µm. These images were initially downscaled to 12.5% (320 µm isovoxel) of their original size. At this resolution, a threshold was set isointense to bone and through erosion and dilation, and identifying volume enclosed by bone, the void inside the femur was filled to identify the position of the femur in the scan. A multistep procedure was used to find the regions of interest. As a first step, the coordinates of the estimated center of the femur head and center of the neck were determined manually. Next, using these coordinates, the radius of the head was approximated as a percentile of the distance of voxels in the femoral head to the estimated center. For this measurement, only voxels which were located further from the neck than the approximated center were considered. Then, based on these initial measurements, the center of the head and neck were repositioned. From these new coordinates, the radius of the femoral head was measured and the final coordinates determined. Using these coordinates and the measured radius, the final positions of head and neck were determined. The neck and head regions were limited by planes perpendicular to the axis between head and neck center. Based on initial observation of the samples, the following dimensional parameters were selected to define the region of interest. The head was defined along this axis as a region from its most distal part to a plane 1.33 times the radius distant. The neck reached a plane 2.33 times the length of the radius. Segmentation between the cortical and trabecular compartments is challenging because there is rarely a precise border between them [28]. Therefore, to exclude the cortical bone, parts of the head and neck which were < 10% of the diameter away from the outside of the femur were excluded. Additionally, if cortical bone, defined as the outer bone layer with at least a local bone volume fraction of 75%, still reached into the measurement region in the center, it was also excluded. Regions within the trabecular bone with a local bone volume fraction of more than 75% were identified and measured separately because the bone in these regions revealed to lack a regular trabecular structure. The resulting regions of interest were copied to the full resolution images (40 µm). The bone inside the different regions was thresholded and BV/TV was measured. The regions were then exported as image stacks. The original scans and regions of interest were imported into Fiji (Fiji [24] + ImageJ) [25] and trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), bone surface (BS), and connectivity density (Conn.D) were measured using the BoneJ plugin [26]. Due to the large size of the region of interest and excessive amount of processing power required, the images were downsized to 50% (80 µm isovoxel) of their original resolution for these measurements.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean and standard deviation. A Pearson Chi-square test was used for the semi-quantitative analyses to find association between various parameters with respect to PDB. Furthermore, a homogeneity test was employed to determine equal or unequal variance. Differences between non-affected and Pagetic groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM-SPSS, version 24.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Bone Samples

The demographic characteristics of our samples are presented in Table 1. For femoral samples: mean (SD) age was 78.5 (13.3) and 65.6 (6.5) years in non-affected and Pagetic, respectively. In the non-affected group (n = 13) there were 9 males (69.2%) and 4 females (30.8%), and in the Pagetic group (n = 10) 3 males (30.0%), 6 females (60.0%), and 1 was unknown (10%). For tibial samples, mean (SD) age was 76.9 (14.9) and 69.2 (9.5) years in non-affected and Pagetic, respectively. The non-affected group (n = 10) consisted of 6 males (60%),and 4 females (40%), and the Pagetic group (n = 10) consisted of 3 males (30%), 2 females (20%), and 5 were unknown (50%).

µCT Imaging Studies

Microcomputed tomography images at the midshaft of the Pagetic femora showed cortical thickening, marked cortical porosity, and trabecularization of cortical structures (Fig. 2a, c). Similar alterations were also present in the affected tibiae (Fig. 2b, d). At the trabecular compartments, severe structural disorganization and trabecular defects were noted; the remaining trabeculae appeared thickened (Fig. 3).

Semi-quantitative Grading

Semi-quantitative grading of cortical architectural parameters of the femoral midshaft showed higher thickness of cortices (p = 0.011), higher porosity (p < 0.001), and increased trabecularization (p = 0.011) when comparing Pagetic to non-affected bones (Fig. 4). Semi-quantitative grading of cortical architectural parameters of the tibial midshaft showed higher thickness of cortices (p = 0.008), porosity and trabecularization (both, p < 0.001) when comparing Pagetic to non-affected bones (Fig. 5).

Semi-quantitative grading of trabecular architectural parameters of the proximal femur showed higher thickness of trabeculae (p < 0.001) and separation of trabeculae (p = 0.037), but lower amount of trabeculae (p = 0.023) in the Pagetic compared to non-affected bones (Figs. 3, 4). Semi-quantitative grading of trabecular architectural parameters of the tibial condyle showed higher trabecular defects (p = 0.015), thickness of trabeculae (p = 0.019), and separation of trabeculae (p < 0.001), but a lower amount of trabeculae (p = 0.012) in the Pagetic compared to non-affected bones (Fig. 5).

Cortical and Trabecular Bone Microarchitecture

Numerical analysis of the cortical bone of the femurs is shown in Fig. 6. Analysis of the femoral cortical parameters showed lower total bone volume (BV) and lower bone volume in the outer region (66–100%) (− 36%, p = 0.004, and − 50%, p < 0.001, respectively), lower total volume (TV) in the outer region (66–100%) (− 42%, p < 0.001), and lower total BV/TV and BV/TV in the outer region (66–100%) (− 23%, and − 12%, p < 0.001, respectively) in Pagetic compared to non-affected bones. However, both BV and TV in the middle region (33–66%) and BV/TV in the inner region (0–33%) were higher (123%, p = 0.011 for BV, 147%, p = 0.010 for TV, and 33%, p = 0.025 for BV/TV, respectively) in Pagetic compared to non-affected bones.

Cortical bone microarchitecture in Pagetic versus non-affected femora. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. BV bone volume, TV total volume, BV/TV bone volume fraction. Percentages mean the different regions within the midshaft of the bone, considering the 100% value the outside part, and < 33% value the inner part of the midshaft

Numerical analysis of trabecular regions of the femoral head and neck is presented in Table 2. Analyses of the femoral trabecular parameters showed higher BV/TV (96%, p = 0.008) and Tb.Th (43%, p = 0.004) in the femoral neck in Pagetic compared to non-affected bones.

Discussion

Analysis of bone structure in Paget’s disease on a quantitative (histomorphometric) level is surprisingly rare. A histomorphometric study [29], which was carried out in two historic skeletons with PDB, found evidence of an increased Tb.Th in the femoral shaft, the calcaneus, and in the sacrum, respectively. Histomorphometric results from Seitz et al. [4] showed a high bone turnover with a significant increase in bone resorption and bone formation indices (Tb.N, osteoid volume and osteoid surface, osteoblast number, and surface of osteoclasts) and an increased BV in Pagetic iliac crests. Likewise, Meunier et al. [10] reported an increased trabecular BV, excessive resorption surfaces, and elevated osteoid surfaces in iliac bone biopsies of Pagetic patients. In agreement with these data, our µCT-based imaging analysis of the Pagetic trabecular architecture of both the femoral head and the tibial condyle shows thickening of the trabeculae and higher separation of trabeculae, but decreased amount of trabeculae (Fig. 3). Furthermore, in the histomorphometric study by Pestka et al. [11], affected vertebral body biopsies revealed a significant increase both in trabecular BV as well as osteoid parameters. In comparison to histomorphometric data obtained from extra-spinal skeletal locations affected by PDB (i.e., iliac crest), a similar bone microarchitecture of the vertebral bodies was observed. They concluded that vertebral body height and the spine BV together with bone density might play an important role in the manifestation of Pagetic bone alterations [11]. In another histopathology study,[30] based on temporal bone of only eight subjects, no quantitative results are presented.

In addition, Cherian et al. [31] observed that cortical and trabecular bone density was increased in vertebrae affected by PDB. Nevertheless, cortical quantitative CT values were underestimated in PDB compared with physical measurements of density [31]. In contrast to the above-mentioned data on the lumbar spine, we have observed differences in the thickness of cortices as well as an increased porosity, and trabecularization of the compact bone in the midshaft of the Pagetic femurs and tibias (Fig. 2a–d).

Consistent with the imaging findings, numerical analyses in this study have shown that BV/TV was lower in Pagetic femoral cortical midshafts than in the non-affected bones. For additional analyses, the cortex of the midshaft was subdivided (from inside to outside) into three subregions (i.e., inner: 0–33%, middle: 33–66%, and outer: 66–100%) (Fig. 1a) considering the 100% value in the outside part, and < 33% value in the inner part of the midshaft. Interestingly, in Pagetic femora, the BV/TV of the outer—but not of the inner cortex—was significantly decreased (Fig. 6). Moreover, we have also observed decreased BV and TV of the outside part of the cortex. This could suggest a higher risk of fractures since cortical porosity and trabecularization of cortical structures have been associated with an increased fracture risk [32, 33]. In this context, Van Staa et al. [34] evaluated epidemiologic and clinical aspects of PDB in England and Wales using the General Practice Research Database. They described that patients with PDB had an increased risk of fractures (relative risk: 1.2) when compared to matched controls; remarkably, the risk of hip fractures was increased by 44%. The structural alterations observed in long bones with Paget’s disease—in particular, those seen at the cortices—could thus be indicative of impaired bone strength. On the other hand, regarding the trabecular compartment of the Pagetic femurs, we have observed that Tb.Th of the femoral neck was increased [29]. In agreement with the studies by Seitz et al. [4] and Meunier et al. [10] performed at the iliac crests, and by Pestka et al. [11] in the spine, we have also noticed increased trabecular BV/TV at the Pagetic femoral neck (Table 2). When both trabecular regions (head and neck) were combined, a trend toward diminished Conn.D in Pagetic femurs was seen. Interestingly, osteoporotic patients are characterized by reduced Conn.D at the femoral neck [35]. In line with our data, and taking into account that cortical porosity and severe trabecular defects were found to be present in our series of specimens, we may assume that bone strength could be diminished despite the increased Tb.Th and BV/TV leading to an elevated fracture risk [36, 37]. However, the reliability of these opposed phenomena should be further analyzed in biomechanical studies to confirm the consequences. It is also well known that cortical porosity increases with diabetes [38], and it may be the case that these observed changes in our study are not specific of PDB but might also coexist with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Since genetic factors inducing type 2 diabetes are very complex, even aDNA analyses of the bones would not give us sufficient information to decide whether these individuals were affected by both PDB and type 2 diabetes.

The structural differences between cortical and cancellous bone are widely recognized [39]. However, less is known about the complex changes concerning either architecture or thickness of bone in patients suffering from skeleton-affecting diseases. Deeper insight into the regular distribution and architecture of cancellous bone within the human skeleton seems to be essential to better understand both, the role of bone cellular activity and also the diagnostic validity of BV measurements [40]. There are striking differences between peripheral and axial measurement sites and even between local areas within these sites. Generally, in healthy subjects, trabecular BV at the femoral neck (15.8%) is higher than at the lumbar spine (8.3%) or the iliac crest (11.5%). Of note, there is a systematic variation in trabecular microarchitecture of the iliac crest, showing highest bone mass within the anterior part and lower values for the medial and dorsal part [40].

Several potential limitations of the present study should be mentioned. There are differences in age-related variations of cortical and trabecular bone for both women and men. Many studies have evaluated the age- and sex-related changes in the cortical and trabecular bone microarchitecture [41,42,43,44]. There is increasing clinical interest in assessing bone microstructure, with the ultimate goal of improving the prediction of fracture risk [41]. It is well known that cortical porosity as well as Tb.Sp increase with age, and it might be the case that these observed changes in our study are not specific of PDB. However, we have noticed quite severe alterations in the specimens of this study obtained from Pagetic subjects aged 66 ± 6 years. The mean age and age variability of the non-affected subjects was larger (average age: 79 ± 13 years) than the Pagetic ones. It is important to note that, according to the records of the collection, in some Pagetic subjects, the age was not known. Even considering the fact that cortical porosity and Tb.Sp increase (and cortical thickness decreases) [43] with age, the Pagetic bones are extensively overshooting the age effect. Interestingly, in a longitudinal study, Shanbhogue et al. [44] stated that both in women and men, parameters of trabecular microarchitecture at the tibia did not change with age. Thus, we may assume that the alterations seen in the cancellous compartment are caused by the metabolic bone disorder. Since the age at which the diagnosis of PDB was established in our samples is not known, another limitation is that some of the observed microarchitectural changes may correlate with specific gene alterations which increase or decrease the susceptibility to develop the disease [45].

High-resolution peripheral QCT (HR-pQCT) allows acquisition of images which enable the characterization of cortical and trabecular microarchitecture in unique detail [44]. Moreover, this technology can provide novel and contemporary clinical information about the differential diagnosis of the disease. Several studies [41, 43, 44] have demonstrated sexual dimorphisms in bone microstructure, and particularly different patterns of bone loss associated with increasing age which leads to weaker bones in postmenopausal women [44]. There seems to be, however, agreement on a dominance of cortical over trabecular bone loss in both sexes. Given the small sample sizes in our study, sexes were not balanced in the Pagetic and control group which limits the conclusions with regard to sexual dimorphisms. The magnitude of structural alterations in Pagetic bone samples was nevertheless found to be similar in both sexes (Figs. 4, 5; Table 1).

According to the study by Smith et al. [46], which divided the spectrum of the pathologic alterations of the PDB into three stages: the lytic phase (incipient-active), in which osteoclasts predominate; the mixed phase (active), in which osteoblasts cause repair superimposed on the resorption; and the blastic phase (late-inactive) in which osteoblasts predominate and areas of sclerosis may develop. Due to a lack of clinical data, it was not possible to determine in which phase of the disease the affected subjects were at the time of death. However, we could assume that Pagetic subjects were in a mixed phase of the disease, since sclerosis was infrequently observed. The cause of death was unknown; nevertheless, we did not observe Paget sarcoma in any of our specimens.

Beside the clinical and differential diagnostic relevance of our study, PDB is also a matter of interest in paleopathology: the earliest reference to PDB in archeological human remains was reported by Pales [47], which included a brief discussion of a femur from the Neolithic in France. There was considerable anterior curvature of the diaphysis with a marked expansion of the cortex. Moreover, five cases of PDB in prehistoric skeletons from the United States were published by Denninger [48]. In all cases, the long bones had a thickened cortex. However, neither X-ray inspection nor histology was used in any of these studies, making the diagnosis likely but not certain [49]. Wells and Woodhouse [50] investigated a skeleton recovered from a burial ground in England, which was characterized by bowed long bones. The authors’ diagnosis of PDB was based on the deformation of bones and the features observed in the X-rays of the femora and vertebrae in plain radiograms [49]. With regard to paleopathology, our findings—obtained by a non-invasive technique—will substantially aid to the differential diagnosis of PDB of historic skeletal remains. In contemporary clinical practice, biopsies of long bones for suspected Paget’s disease are performed only in rare cases; nevertheless, our µCT findings also in this setting could contribute to establish a diagnosis.

Finally, the current investigation could be useful and support several studies related to the bone microstructure analyses in experimental models (i.e., transgenic animal models) of Paget’s disease [51, 52].

Conclusions

In conclusion, in weight-bearing long bones, PDB is responsible for major structural alterations both at cortical and trabecular sites. The main findings of this study were (i) femurs and tibias affected by PDB showed marked cortical porosity, and trabecularization of cortical structures. (ii) PDB was also associated with severe disorganization of trabecular structures, trabecular defects, and thickening of (remaining) trabeculae. These findings are relevant for the differential diagnosis of PDB and for the pathogenesis of associated complications, since the disorder produces abnormalities in the structure that might lead to bone fragility, increasing bone fracture risk, enhanced by low bone mass, and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue [36, 53].

References

Paget J (1877) On a form of chronic inflammation of bones (osteitis deformans). Med Chir Trans 60:37–64.9

Kanis JA (1992) Pathophysiology and treatment of Paget’s disease of bone. Martin Dunitz, London

Ralston SH, Layfield R (2012) Pathogenesis of Paget disease of bone. Calcif Tissue Int 91:97–113

Seitz S, Priemel M, Zustin J, Beil FT, Semler J, Minne H, Schinke T, Amling M (2009) Paget’s disease of bone: histologic analysis of 754 patients. J Bone Miner Res 24:62–69

Singer FR, Bone HG III, Hosking DJ, Lyles KW, Murad MH, Reid IR, Siris ES (2014) Paget’s disease of bone: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:4408–4422

Schmorl G (1932) Über Ostitis deformans Paget. Virchows Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medizin 283:694–751

Siris ES, Roodman GD (2013) Paget’s disease of bone. In: Rosen CJ (ed) Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, pp 659–668

Lojo Oliveira L, Torrijos Eslava A (2012) Treatment of Paget’s disease of bone. Reumatol Clin 8:220–224

Seitz S, Priemel M, von Domarus C, Beil FT, Barvencik F, Amling M, Rueger JM (2008) The second most common bone disease: a review on Paget’s disease of bone. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 34:549–553

Meunier PJ, Coindre JM, Edouard CM, Arlot ME (1980) Bone histomorphometry in Paget’s disease. Quantitative and dynamic analysis of pagetic and nonpagetic bone tissue. Arthritis Rheum 23:1095–1103

Pestka JM, Seitz S, Zustin J, Puschel K, Amling M, Barvencik F (2012) Paget disease of the spine: an evaluation of 101 patients with a histomorphometric analysis of 29 cases. Eur Spine J 21:999–1006

Takigami I, Ohara A, Matsumoto K, Fukuta M, Shimizu K (2010) Functional bracing for delayed union of a femur fracture associated with Paget’s disease of the bone in an Asian patient: a case report. J Orthop Surg Res 5:33

Patsch JM, Burghardt AJ, Kazakia G, Majumdar S (2011) Noninvasive imaging of bone microarchitecture. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1240:77–87

Jiang Y, Zhao J, Liao EY, Dai RC, Wu XP, Genant HK (2005) Application of micro-CT assessment of 3-D bone microstructure in preclinical and clinical studies. J Bone Miner Metab 23(Suppl 1):122–131

Keaveny TM (2010) Biomechanical computed tomography-noninvasive bone strength analysis using clinical computed tomography scans. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1192:57–65

Portele KA (1990) Die Sammlung mazerierter Skelette und Knochen des Pathologisch-anatomischen Bundesmuseums in Wien: (postcraniale Knochen), Teil II. Mitteilungen des Pathologisch-anatomischen Bundesmuseums in Wien

Ortner DJ, Putschar WGJ (1981) Identification of pathological conditions in human skeletal remains. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Steinmann W (1982) Makroskopische Präparationsmethoden in der Medizin. Thieme, Stuttgart, pp 10–19

Dawson AB (1926) A note on the staining of the skeleton of cleared specimens with alizarin red S. Stain Technol 1:123–124

Onwuama KT, Salami SO, Ali M, Nzalak JO (2012) Effect of different methods of bone preparation on the skeleton of the African giant pouched rat (Cricetomys gambianus). Int J Morphol 30:425–427

Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR (1987) Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2:595–610

Tan A, Goodman K, Walker A, Hudson J, MacLennan GS, Selby PL, Fraser WD, Ralston SH, for the P-EZTG (2017) Long-term randomized trial of intensive versus symptomatic management in Paget’s disease of bone: the PRISM-EZ study. J Bone Miner Res 32:1165–1173

Corral-Gudino L, Borao-Cengotita-Bengoa M, Del Pino-Montes J, Ralston S (2013) Epidemiology of Paget’s disease of bone: a systematic review and meta-analysis of secular changes. Bone 55:347–352

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682

Schindelin J, Rueden CT, Hiner MC, Eliceiri KW (2015) The ImageJ ecosystem: an open platform for biomedical image analysis. Mol Reprod Dev 82:518–529

Doube M, Klosowski MM, Arganda-Carreras I, Cordelieres FP, Dougherty RP, Jackson JS, Schmid B, Hutchinson JR, Shefelbine SJ (2010) BoneJ: free and extensible bone image analysis in ImageJ. Bone 47:1076–1079

Serra J (1983) Image analysis and mathematical morphology. Academic Press, Inc., London

Sornay-Rendu E, Boutroy S, Duboeuf F, Chapurlat RD (2017) Bone microarchitecture assessed by HR-pQCT as predictor of fracture risk in postmenopausal women: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res 32:1243–1251

Aaron JE, Rogers J, Kanis JA (1992) Paleohistology of Paget’s disease in two medieval skeletons. Am J Phys Anthropol 89:325–331

Dimitriadis PA, Bamiou D-E, Bibas AG (2012) Hearing loss in Paget’s disease: a temporal bone histopathology study. Otol Neurotol 33:142–146 https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e318241c3bd

Cherian RA, Haddaway MJ, Davie MW, McCall IW, Cassar-Pullicino VN (2000) Effect of Paget’s disease of bone on areal lumbar spine bone mineral density measured by DXA, and density of cortical and trabecular bone measured by quantitative CT. Br J Radiol 73:720–726

Seeman E (2015) Growth and age-related abnormalities in cortical structure and fracture risk. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 30:419–428

Shigdel R, Osima M, Lukic M, Ahmed LA, Joakimsen RM, Eriksen EF, Bjornerem A (2016) Determinants of transitional zone area and porosity of the proximal femur quantified in vivo in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 31:758–766

van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, Lyles K, Sprafka JM, Cooper C (2002) Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res 17:465–471

Föger-Samwald U, Vekszler G, Hörz-Schuch E, Salem S, Wipperich M, Ritschl P, Mousavi M, Pietschmann P (2016) Molecular mechanisms of osteoporotic hip fractures in elderly women. Exp Gerontol 73:49–58

Tranquilli Leali P, Doria C, Zachos A, Ruggiu A, Milia F, Barca F (2009) Bone fragility: current reviews and clinical features. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 6:109–113

Melton LJ III, Tiegs RD, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM (2000) Fracture risk among patients with Paget’s disease: a population-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 15:2123–2128

Samelson EJ, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Zhang X, Xu H, Liu CT, Boyd SK, McLean RR, Broe KE, Kiel DP, Bouxsein ML (2018) Diabetes and deficits in cortical bone density, microarchitecture, and bone size: Framingham HR-pQCT study. J Bone Miner Res 33:54–62

Foldes J, Parfitt AM, Shih MS, Rao DS, Kleerekoper M (1991) Structural and geometric changes in iliac bone: relationship to normal aging and osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 6:759–766

Amling M, Herden S, Posl M, Hahn M, Ritzel H, Delling G (1996) Heterogeneity of the skeleton: comparison of the trabecular microarchitecture of the spine, the iliac crest, the femur, and the calcaneus. J Bone Miner Res 11:36–45

Khosla S, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, Oberg AL, McDaniel LJ, Holets M, Peterson JM, Melton LJ (2006) Effects of sex and age on bone microstructure at the ultradistal radius: a population-based noninvasive in vivo assessment. J Bone Miner Res 21:124–131

Burt LA, Liang Z, Sajobi TT, Hanley DA, Boyd SK (2016) Sex- and site-specific normative data curves for HR-pQCT. J Bone Miner Res 31:2041–2047

Chen H, Zhou X, Shoumura S, Emura S, Bunai Y (2010) Age- and gender-dependent changes in three-dimensional microstructure of cortical and trabecular bone at the human femoral neck. Osteoporos Int 21:627–636

Shanbhogue VV, Brixen K, Hansen S (2016) Age- and sex-related changes in bone microarchitecture and estimated strength: a three-year prospective study using HRpQCT. J Bone Miner Res 31:1541–1549

Ralston SH, Albagha OM (2011) Genetic determinants of Paget’s disease of bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1240:53–60

Smith SE, Murphey MD, Motamedi K, Mulligan ME, Resnik CS, Gannon FH (2002) From the archives of the AFIP. Radiologic spectrum of Paget disease of bone and its complications with pathologic correlation. Radiographics 22:1191–1216

Pales L (1929) Maladie de Paget Prehistorique, avec Note Additionelle du Professeur R. Verneau L´Anthropologie 39:263–270

Denninger HS (1933) Paleopathological evidence of Paget’s disease. Ann Med Hist 5:73–81

Ortner DJ (2003) Miscellaneous bone diseases. In: Ortner DJ (ed) Identification of pathological conditions in human skeletal remains. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 435–452

Wells C, Woodhouse N (1975) Paget’s disease in an Anglo-Saxon. Med Hist 19:396–400

Daroszewska A, Rose L, Sarsam N, Charlesworth G, Prior A, Rose K, Ralston SH, van ‘t Hof RJ (2018) Zoledronic acid prevents pagetic-like lesions and accelerated bone loss in the p62(P394L) mouse model of Paget’s disease. Dis Models Mech. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.035576

Daroszewska A, van ‘t Hof RJ, Rojas JA, Layfield R, Landao-Basonga E, Rose L, Rose K, Ralston SH (2011) A point mutation in the ubiquitin-associated domain of SQSMT1 is sufficient to cause a Paget’s disease-like disorder in mice. Hum Mol Genet 20:2734–2744

D’Elia G, Caracchini G, Cavalli L, Innocenti P (2009) Bone fragility and imaging techniques. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 6:234–246

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Elena Nebot, Patrick Heimel, Stefan Tangl, Martin Dockner, Janina Patsch, Gerhard W. Weber, Michael Pretterklieber, Maria Teschler-Nicola, and Peter Pietschmann declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK Nr: 1459/2014). The control bones provided by the Division of Anatomy were obtained from voluntary body donors who gave permission for the use of their remnants for teaching and research.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nebot, E., Heimel, P., Tangl, S. et al. Paget’s Disease of Long Bones: Microstructural Analyses of Historical Bone Samples. Calcif Tissue Int 105, 15–25 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-019-00539-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-019-00539-8