Abstract

Objective

Acute brain dysfunction or delirium occurs in the majority of mechanically ventilated (MV) medical intensive care unit (ICU) patients and is associated with increased mortality. Unfortunately delirium often goes undiagnosed as health care providers fail to recognize in particular the hypoactive form that is characterized by depressed consciousness without the positive symptoms such as agitation. Recently, clinical tools have been developed that help to diagnose delirium and determine the subtypes. Their use, however, has not been reported in surgical and trauma patients. The objective of this study was to identify the prevalence of the motoric subtypes of delirium in surgical and trauma ICU patients.

Methods

Adult surgical and trauma ICU patients requiring MV longer than 24 h were prospectively evaluated for arousal and delirium using well validated instruments. Sedation and delirium were assessed using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) and the Confusion Assessment Method in the ICU (CAM-ICU), respectively. Patients were monitored for delirium for a maximum of 10 days or until ICU discharge.

Patients

A total of 100 ICU patients (46 surgical and 54 trauma) were enrolled in this study. Three patients were excluded from the final analysis because they stayed persistently comatose prior to their death.

Measurements and results

Prevalence of delirium was 70% for the entire study population with 73% surgical and 67% trauma ICU patients having delirium. Evaluation of the subtypes of delirium revealed that in surgical and trauma patients, hypoactive delirium (64% and 60%, respectively) was significantly more prevalent than the mixed (9% and 6%) and the pure hyperactive delirium (0% and 1%).

Conclusions

The prevalence of the hypoactive or “quiet” subtype of delirium in surgical and trauma ICU patients appears similar to that of previously published data in medical ICU patients. In the absence of active monitoring with a validated clinical instrument (CAM-ICU), however, this subtype of delirium goes undiagnosed and the prevalence of delirium in surgical and trauma ICU patients remains greatly underestimated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute brain dysfunction or delirium is defined as a disturbance of consciousness characterized by fluctuating mental status, inattention, and disorganized thought. Recent studies using standardized and validated tools have shown that delirium is exceedingly common in ventilated [1, 2] and nonventilated [3] medical ICU (MICU) patients and is a predictor of a threefold higher mortality over 6 months [4], higher cost of care [5], and significant ongoing cognitive impairment among survivors even after adjusting for important covariates [6]. Unfortunately, many different terms have been used to describe the spectrum of acute brain dysfunction in critically ill patients including ICU psychosis, ICU syndrome, acute confusional state, septic encephalopathy, and acute brain failure [7–9]. The current consensus of many is to consistently use the unifying term delirium and subcategorize according to level of alertness (hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed) [10]. The lack of validated bedside monitoring instruments for diagnosing delirium and the need to have formal evaluations by psychiatrists have further prevented delirium detection in the past, especially in nonverbal patients on mechanical ventilation (MV) [9].

With the development of tools such as the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist [11], Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) [12], and Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) [1] nonpsychiatric physicians and other healthcare personnel can now reliably diagnose delirium even under MV. The Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) has therefore recently proposed guidelines [13] for more routine and diligent monitoring of delirium as part of standard of care. Despite this very few ICUs actually monitor for delirium using these instruments [14], resulting in underdiagnosis of delirium [9], particularly the hypoactive delirium that is characterized by depressed consciousness. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of the motoric subtypes of delirium among MV surgical and trauma ICU patients in a tertiary university hospital setting.

Methods

Patient selection

The institutional review board approved this study, with a waiver of consent. Enrollment criteria included all adult patients requiring MV longer than 24 h admitted to the surgical or trauma ICUs at Vanderbilt University's 631-bed medical center. Our aim was to enroll 100 consecutive patients, which was achieved in the span of 5 months from November 2004 to March 2005. Exclusion criteria included significant baseline neurological diseases or intracranial neurotrauma that would confound the evaluation of delirium, inability to understand English, significant hearing loss and moribund patients not expected to survive longer than 24 h. The study evaluated included 142 patients from the surgical and trauma ICU for eligibility in the study. Of these, 40 were excluded due to significant neurological injury and two patients were moribund and not expected to survive for greater than 24 h. A total of 100 patients were thus enrolled in the study. Three patients remained comatose for the entire duration of the study, subsequently died, and hence are not included in the analysis. Demographic data on the remaining 97 patients are presented in Table 1.

Sedation assessment

Level of arousal was measured by using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) [15, 16] which is a ten-point scale ranging from +4 to −5, with a RASS score of 0 denoting a calm and alert patient. Positive RASS scores denote positive or aggressive symptoms ranging from +1 (mild restlessness) to +4 (dangerous agitation). The negative RASS scores differentiate between response to verbal commands (RASS score −1 to −3) and physical stimulus (RASS score −4 and −5). Furthermore the RASS incorporates a component of the “content of consciousness” by assigning a sedation score to the response to the verbal stimulus, based on the duration of eye contact (−1 for patients with eye contact > 10 s, −2, for those < 10 s, and −3 for no eye contact but response to verbal stimulus). Nursing staff performs and documents the patients RASS hourly while in the ICU and on an every four to 8-h basis while on a step-down or general medical-surgical floor. A RASS assessment was performed by the study members in conjunction with the CAM-ICU assessment once daily in the morning between 10 a.m. and noon unless the patient was unavailable for assessment due to scheduled procedures.

Delirium assessment

Patients were further evaluated once daily for delirium using the CAM-ICU [1] for a maximum of 10 days or until ICU discharge. This delirium assessment instrument is valid [1, 2] and extremely reliable in the hands of health care providers, taking an average of 60–90 s for the bedside nurses [17]. The CAM-ICU comprises four features which assess the following: acute change or fluctuation in mental status (feature 1), inattention (feature 2), disorganized thinking (feature 3), and altered level of consciousness (feature 4). From this the patient was categorized as being delirious, in a coma, or being normal based on standardized definitions in the validation study of the CAM-ICU [1]. To be diagnosed as delirious one needed to have a RASS score of −3 or higher, with an acute change or fluctuation in mental status (feature 1), accompanied by inattention (feature 2), and either disorganized thinking (feature 3) or an altered level of consciousness (feature 4). Coma was defined as a RASS score of −4 or −5 where the CAM-ICU could not be assessed. Normal was defined as RASS scores −3 and above and CAM-ICU negative. Patients were considered delirious, comatose, or normal for the entire day if they were CAM-ICU positive, unable to assess or CAM-ICU negative, respectively, during the daily cognitive assessment by the study staff. Prevalent delirium was defined as a positive CAM-ICU assessment during the first noncomatose mental status evaluation. We chose to evaluate and label our delirium assessment as prevalent delirium instead of incident delirium (the first positive CAM-ICU assessment following a period of normal mental status) because it was difficult to obtain a reliable assessment of a patients' preenrollment delirium status prior to ICU admission especially in the trauma patients. We believe most of our patients were not delirious prior to their ICU admission, and that the new or incident delirium rates would be the same as the prevalent delirium rates, thus not impacting the results of this study.

Motoric subtypes

The existence of hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed clinical subtypes of delirium is widely accepted although its prevalence has not been evaluated in the surgical and trauma ICU patients. Data from non-ICU and medical ICU patients show that the hyperactive form of delirium is the most easily appreciated subtype (due to its increased level of motor activity), but most authors have shown it to actually be the least common motoric subtype [18–21]. On the other hand, most patients manifest hypoactive delirium, but this goes largely unrecognized in the absence of validated delirium monitoring instruments [18, 19]. We classified patients into the motoric subtypes based on the criteria used by Peterson et al. [18]: Hyperactive; a patient only had positive RASS scores (+1 to +4) associated with every CAM-ICU positive assessment, hypoactive; a patient only had RASS scores between 0 and −3 associated with every CAM-ICU positive assessment, and mixed if a patient had some positive RASS scores (+1 to +4) and some RASS scores between 0 and −3 associated with every CAM-ICU positive assessment.

Assessor background

Daily assessments were performed by the research nurses and physician authors who are members of the ICU Delirium and Cognitive Impairment Study Group (http://www.icudeliumu.org). All evaluators received training on both the RASS and CAM-ICU tools, with observation of initial assessments as well as interrater reliability evaluations by senior members of the group (who were involved in the initial validation study of the RASS and the CAM-ICU).

Statistical analysis

Patients' baseline demographic and clinical variables are presented using medians and interquartile range (IQRs) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. For all analyses R-software version 2.1.1 (http://www.pr-project.org) and SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C., USA) were used, and two-tailed 5% significance level was used for all statistical inferences.

Results

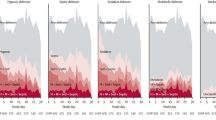

We found that 70% of the combined surgical and trauma ICU patients had at least one episode of delirium. Further evaluation of the subtypes of delirium revealed that in surgical and trauma patients hypoactive delirium (64% and 60% respectively) was significantly more prevalent than the mixed (9% and 6%) and the pure hyperactive delirium (0% and 1%), as shown in Fig. 1. The median duration of delirium was 1 day (IQR 0–4] and ICU length of stay 5 days (3–10).

Discussion

Delirium is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a disturbance of consciousness with inattention accompanied by a change in cognition or perceptual disturbance that develops over a short period of time (hours to days) and fluctuates over time. Many different terms have been used to describe the spectrum of cognitive impairment in critically ill patients including ICU psychosis, ICU syndrome, acute confusional state, septic encephalopathy, and acute brain failure [7–9]. This has made it difficult for clinicians to truly appreciate the magnitude of this unrecognized form of brain dysfunction. The current consensus of many is to consistently use the unifying term delirium and subcategorize according to level of alertness (hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed) [10]. This will help health care providers understand that delirium is not synonymous with only the agitated patient, but that patients can also present with lethargy and inattention.

Our study demonstrates that the majority of surgical and trauma ICU patients have hypoactive delirium. This delirium subtype is characterized by withdrawal, flat affect, apathy, lethargy, and decreased responsiveness [20–22]. These findings complement those of other studies, in medical patients, which have shown that this form of delirium is very common and in many circumstances actually more deleterious, with worse outcomes and more long-term cognitive effects [21]. This appears to be in part due to the fact this form of delirium is unrecognized (and therefore untreated or mismanaged) in 66% to 84% of patients [23–26]. Hyperactive delirium, which is rare in the pure form, is associated with a better overall prognosis [21] and is characterized by agitation, restlessness, and emotional lability [10, 19]. This subtype is often referred to as ICU psychosis and has been traditionally considered by health care providers to be the only form of delirium. Similar to our study, Peterson et al. [18] have reported the rates of these subtypes in MICU patients to be 43.5% hypoactive, 54.1% mixed and 1.6% pure hyperactive.

Our study and those by others have shown that due to the fluctuating nature of delirium patients may present with a mixed clinical picture or sequentially experience both of these hypoactive or hyperactive subtypes of delirium. Most critical care providers would report that hyperactive delirium is far more common, perhaps because these patients attract attention due to their immediate threat to self and others. One of the major problems faced by clinicians in the past has been the inability to monitor for and diagnose delirium at the bedside in a reliable and time efficient manner without needing specialized psychiatric consults. This is more so in the case of hypoactive delirium, which our study shows is the predominant form of delirium experienced by surgical and trauma patients. Given that delirium is associated with worse outcomes, including higher mortality, in MICU patients [4], these data underscore the importance of regular delirium assessments, in that the majority of delirium episodes are invisible in the absence of active monitoring. With the development of tools such as the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist [11], CAM [12], and CAM-ICU [1] nonpsychiatric physicians and other healthcare personnel can now reliably diagnose delirium even while mechanically ventilated and be able to pick up even hypoactive delirium. This has been endorsed by the SCCM in its clinical practice guidelines, where it has been recommended to monitor patients daily for pain, anxiety, and delirium.

Our study has several limitations that need to be considered. First, this was a single-center study, and the results may not be generalizable to all surgical and trauma ICUs. However, the prevalence rates that we observed are similar to those seen in the medical ICU patients. Second, we did not have an adequate sample size to analyze whether delirium was an independent risk factor for worsened clinical outcomes, since the main aim of this study was to evaluate the motoric subtypes. While delirium has been shown to be associated with increased time on the ventilator, longer ICU and hospital length of stay, higher costs, worse neuropsychological outcomes, and increased mortality in non-ICU and medical ICU patients, few data exist regarding its impact on clinical outcomes in surgical and trauma patients [4, 5, 27–31]. Third, we monitored patients only once daily for a maximum of 10 days. More frequent daily evaluation may have provided more information regarding the fluctuation in mental status and a better understanding on the subtypes of delirium. These limitations provide excellent opportunities for future studies.

Conclusions

At our institution we found the hypoactive delirium to be present in the majority of surgical and trauma patients. Considering that delirium is a predictor of death, prolonged cognitive impairment, and higher cost of care, implementation of routine bedside monitoring appears warranted. Such implementation should improve the ability to diagnosis the hypoactive form of delirium, which would otherwise go unnoticed.

References

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, Hart RP, Dittus R (2001) Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA 286:2703–2710

Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, Speroff T, Gautam S, Bernard GR, Inouye SK (2001) Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 29:1370–1379

Thomason JW, Shintani A, Peterson JF, Pun BT, Jackson JC, Ely EW (2005) Intensive care unit delirium is an independent predictor of longer hospital stay: a prospective analysis of 261 non-ventilated patients. Crit Care 9:R375–R381

Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Dittus RS (2004) Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA 291:1753–1762

Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, Shintani AK, Speroff T, Stiles RA, Truman B, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW (2004) Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med 32:955–962

Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Hart RP, Hopkins RO, Ely EW (2004) The association between delirium and cognitive decline: a review of the empirical literature. Neuropsychol Rev 14:87–98

Granberg A, Engberg B, Lundberg D (1996) Intensive care syndrome: a literature review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 12:173–182

Webb JM, Carlton EF, Geeham DM (2000) Delirium in the intensive care unit: are we helping the patient? Crit Care Nurs Q 22:47–60

Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK (2001) Delirium in the intensive care unit: an under-recognized syndrome of organ dysfunction. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 22:115–126

Milisen K, Foreman MD, Godderis J, Abraham IL, Brooten D (1998) Delirium in the hospitalized elderly: nursing assessment and management. Nurs Clin North Am 33:417–436

Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y (2001) Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med 27:859–864

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI (1990) Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 113:941–948

Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, Riker RR, Fontaine D, Wittbrodt ET, Chalfin DB, Masica MF, Bjerke HS, Coplin WM, Crippen DW, Fuchs BD, Kelleher RM, Marik PE, Nasraway SA Jr, Murray MJ, Peruzzi WT, Lumb PD (2002) Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med 30:119–141

Ely EW, Stephens RK, Jackson JC, Thomason JW, Truman B, Gordon S, Dittus RS, Bernard GR (2004) Current opinions regarding the importance, diagnosis, and management of delirium in the intensive care unit: a survey of 912 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med 32:106–112

Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, Francis J, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, Sessler CN, Dittus RS, Bernard GR (2003) Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA 289:2983–2991

Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK (2002) The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:1338–1344

Pun BT, Gordon SM, Peterson JF, Shintani AK, Jackson JC, Foss J, Harding SD, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW (2005) Large-scale implementation of sedation and delirium monitoring in the intensive care unit: a report from two medical centers. Crit Care Med 33:1199–1205

Peterson JF, Pun BT, Dittus RS, Thomason JW, Jackson JC, Shintani AK, Ely EW (2006) Delirium and its motoric subtypes: a study of 614 critically ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 54:479–484

O'Keeffe ST, Lavan JN (1999) Clinical significance of delirium subtypes in older people. Age Ageing 28:115–119

Meagher DJ, Hanlon DO, Mahony EO, Casey PR, Trzepacz PT (2000) Relationship between symptoms and motoric subtype of delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 12:51–56

Meagher DJ, Trzepacz PT (2000) Motoric subtypes of delirium. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 5:75–85

Justic M (2000) Does “ICU psychosis” really exist? Crit Care Nurs 20:28–37

Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, Ludwig LE, Muraca B, Haslauer CM, Donaldson MC, Whittemore AD, Sugarbaker DJ, Poss R, (1994) A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA 271:134–139

Inouye SK (1994) The dilemma of delirium: clinical and research controversies regarding diagnosis and evaluation of delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients. Am J Med 97:278–288

Sanders AB (2002) Missed delirium in older emergency department patients: a quality-of-care problem. Ann Emerg Med 39:338–341

Hustey FM, Meldon SW (2002) The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 39:248–253

McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, Belzile E, Primeau F (2001) Delirium in older medical inpatients and subsequent cognitive and functional status: a prospective study. Can Med Assoc J 165:575–583

McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, Primeau F, Belzile E (2002) Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med 162:457–463

McClusker J, Cole MG, Dendukuri N, Belzile E (2003) Does delirium increase hospital stay? J Am Geriatr Soc 51:1539–1546

Lin SM, Liu CY, Wang CH, Lin HC, Huang CD, Huang PY, Fang YF, Shieh MH, Kuo HP (2004) The impact of delirium on the survival of mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med 32:2254–2259

Ely EW, Gautam S, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Speroff T, Truman B, Dittus R, Bernard R, Inouye SK (2001) The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med 27:1892–1900

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA (1992) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45:613–619

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE (1985) APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 13:818–829

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, de Mendonca A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG (1996) The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med 22:707–710

Vincent JL, Mendonca AD, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter P, Sprung CL, Colardyn F, Blecher S, on behalf of the working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (1998) Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Crit Care Med 26:1793–1800

Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB (1974) The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 14:187–196

Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Copes WS, Gann DS, Gennarelli TA, Flanagan ME (1989) A revision of the Trauma Score. J Trauma 29:623–629

Boyd CR, Tolson MA, Copes WS (1987) Evaluating trauma care: the TRISS method. Trauma Score and the Injury Severity Score. J Trauma 27:370–378

Acknowledgements

P.P. is the recipient of the Vanderbilt Physician Scientist Development Award and the ASCCA–FAER–Abbot Physician Scientist Award. E.W.E. is the Associate Director of Research for the VA Tennessee Valley Geriatric Research and Education Clinical Center. He is a recipient of the Paul Beeson Faculty Scholar Award from the Alliance for Aging Research and is a recipient of a K23 from the National Institute of Health (#AG01023–01A1), a RO–1 from the National Institute of Aging (#AG0727201–A1) and a VA MERIT Award from CSRND. The funding agencies had no role in the design or conduct of the study, data collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data. In addition, they had no role in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0846-1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pandharipande, P., Cotton, B.A., Shintani, A. et al. Motoric subtypes of delirium in mechanically ventilated surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients . Intensive Care Med 33, 1726–1731 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0687-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0687-y