Abstract

Purpose

The precise incidence of trauma in pregnancy is not well-known, but trauma is estimated to complicate nearly 1 in 12 pregnancies and it is the leading non-obstetrical cause of maternal death.

Methods

A retrospective study of all pregnant women presented to national level 1 trauma center from July 2013 to June 2015 was conducted. Descriptive and inferential statistics applied for data analysis.

Results

Across the study period, a total of 95 pregnant women were presented to the trauma center. The average incidence rate of traumatic injuries was 250 per 1000 women of childbearing age presented to the Hamad Trauma Center. The mean age of patients was 30.4 ± SD 5.6 years, with age ranging from 20 to 42 years. The mean gestational age at the time of injury was 24.7 ± 8.7 weeks which ranged from 5 to 37 weeks. The majority (47.7%) was in the third trimester of the pregnancy. In addition, the large majority of injuries was due to MVCs (74.7%) followed by falls (15.8%).

Conclusions

Trauma during pregnancy is not an uncommon event particularly in the traffic-related crashes. As it is a complex condition for trauma surgeons and obstetrician, an appropriate management protocol and multidisciplinary team are needed to improve the outcome and save lives of both the mother and fetus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Traumatic injury during pregnancy is one of the major contributors to maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Physical trauma affects nearly 8% of all pregnant women, which is the leading non-obstetrical cause of maternal deaths [1, 2]. Pregnant women are more prone to have trauma due to physical limitations and presence of special injuries related to trauma and pregnancy. Motor vehicle crashes (MVCs), falls, assaults, domestic violence, homicides and penetrating injuries are the major causes of trauma in pregnant women [8]. MVC was reported as the leading cause [8,9,10,11,12,13,14], with an incidence rate around 207 cases per 100,000 pregnancies (0.21%); the majority of them had gestational age of more than 20 weeks [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Lack of seat belt use was found as the major risk factor for adverse outcomes reflecting a reality of discomfort of advanced pregnancy and the belief that it can increases the risk of injury [12]. The implications of trauma during pregnancy include higher incidences of spontaneous abortion, preterm premature rupture of membranes, uterine rupture, placental abruption, preterm birth, cesarean delivery and stillbirth [3,4,5,6,7]. The challenge of trauma in pregnancy is the presence of two simultaneous victims; the mother and fetus, in addition to the physiological and anatomical changes of pregnancy need to be considered. The rate of fetal death caused by maternal trauma was estimated as 2.3 per 100,000 live births, with placental abruption as the main contributing factor [13, 14]. It was also estimated that 1 out of 3 pregnant women hospitalized for traumatic injuries is likely to deliver during the same hospitalization [11]. The risk for placental abruption is higher with blunt trauma to the abdomen regardless of its severity, whereas penetrating trauma frequently leads to direct fetal injury [8,9,10,11]. A multidisciplinary coordinated approach in management is necessary to optimize both maternal and fetal outcomes [8, 13, 15, 16]. Management of trauma during pregnancy is depending on the severity of injury and should be tackled with prompt maternal stabilization for better outcomes. Estimates of the overall incidence and impact of trauma on maternal and fetal outcomes are scarce in the Middle Eastern Arab countries. The purpose of this retrospective study is to estimate the overall incidence, risk factors and outcomes of traumatic injuries among pregnant women based on the data obtained from the national referral hospital in Qatar.

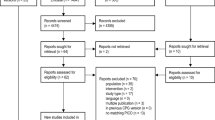

Materials and methods

Study design and the participants

A retrospective study of all pregnant women presented to national level 1 trauma center (Hamad Trauma Center) from July 2013 to June 2015 was conducted. The Hamad trauma center (HTC) is the only level 1 tertiary trauma care facility in Qatar available to serve and treat the traumatic injuries that occurs among the 2.2 million population in the country.

Data collection

Collected data included maternal demographics, mechanism of injury (MOI), types of injury, injury severity scores, comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, parity, gestational age at the time of injury and delivery, birth weight and maternal and fetal outcomes. The incidence rate of traumatic injuries among pregnant women = (total number of pregnant patients presented to the trauma center in a particular year/total number of women of childbearing age presented to the trauma center during that year) × 1000. The childbearing age was defined as 15–44-year-old [17]. The gestational age was presented in weeks. The first trimester of pregnancy refers to week 1 through week 12; second from week 13–27 and the third from week 28 to birth. The delivery in less than gestational age of 37 weeks is referred to as preterm labor; less than 32 weeks as very preterm labor. The gestational age of 24 weeks was considered as the limit of fetal viability. Maternal and fetal outcomes studied include placental abruption, preterm labor, maternal death, low birth weight, fetal distress and fetal or neonatal death. The traumatic injuries were defined according to the ICD-9. Injury Severity Score (ISS) and Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS) were also documented.

Inclusion criteria

Pregnant women were identified by the trauma registry of the institution.

Exclusion criteria

The study excluded trauma patients admitted directly to labor suite without initial assessment by trauma services and patients who died in the prehospital settings.

Sample size calculation

All relevant cases during the study period were included and it is a nationally represented data.

Ethical committee approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Hamad Medical Corporation (#15316/15).

Data management and statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Epi Info version 7.2, Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance (DHIS), Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services (CSELS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road Atlanta, GA30329-4027, USA and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows Version 16.0 (SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied for data analysis, whenever applicable. The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used to generalize the percentages. For all calculations, p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The number of women of childbearing age presented to the trauma center was 201 and 180 during July 2013–June 2014 and July 2014–June 2015, respectively (381 female patients). Across the study period, a total of 95 pregnant women sustained trauma and reported to our HTC. Therefore, the incidence rate of traumatic injuries among pregnant women was 250 per 1000 women of childbearing age per year.

Table 1 shows the overall characteristics of pregnant trauma patients. The mean age of women was 30.4 ± SD 5.6 years (range 20–42). The mean gestational age at the time of injury was 24.7 ± 8.7 weeks which ranged from 5 to 37 weeks. The mean birthweight was 2998.6 ± 696.1. The majority (47.7%) of pregnancies was in the third trimester. The main mechanism of injury was MVCs (74.7%) followed by falls (15.8). Patients’ disposition included TICU admission (n = 6), surgical ward admission (n = 11), transfer to women hospital for further evaluation and management (n = 61), and 17 patients were discharged directly from the trauma room after management (3 discharged against medical advice).

Figures 1 and 2 depict that MVCs were more commonly reported during the second and third trimester of pregnancy. Patients were the drivers in 31% of the relevant MVCs. Extremities fractures were reported in 9.5%, followed by abdominal or pelvic trauma (5.3%). Almost 39% of the patients required hospitalization in which 18.9% were admitted to the trauma intensive care unit (TICU). Over 67% of admissions were into the Women’s Hospital that was located at the same campus in the HTC.

Table 2 shows the pregnancy characteristics, maternal and neonatal outcomes. Pregnant women were followed-up retrospectively for mean duration of 377.2 ± 227.6 days. The mean gestational age at delivery was 35.4 ± 8.7 weeks; 1 out of 3 were pre-term (< 37 weeks), 9.5% were very pre-term, whereas 4.2% were of in less than 24 weeks. Placental abruption reported in 4.2% and labor was induced in 2.1%.

Maternal death was reported in only one case (1.1%). The mean birth weight was 2998.6 ± 696.1 g; low-birth weights in 11.6%. Fetal complications included fetal distress (4.2%), respiratory distress (2.1%) and meconium at delivery (1.1%). Only 2 fetal deaths (2.1%) and 2 neonatal deaths (2.1%) were reported.

Injury severity scorings (ISS and AIS) are given in Table 3. It was found that severe injuries involved mostly the head and chest in 6 women.

Table 4 shows the imaging and interventions in pregnant women after trauma. This table reflects the low use of X-ray and CT scan use in pregnant ladies due to fear of radiation both from the physician and mother/family’s side. Surgical interventions were required in 13 patients.

Figures 3 and 4 show that preterm labor, very preterm labor (included less than 24 week labor), low birth weight, meconium at delivery, fetal distress, and neonatal death were more common in the first trimester. Placental abruption, induction of labor, and maternal and fetal deaths were reported in the second trimester. Respiratory distress in delivered babies was reported only in 2 during the third trimester.

Discussions

Traumatic injury during pregnancy is an outlandish event, transpiring all over the world that needs special care. Previous studies reported that 6–8% of pregnant women could have traumatic injury, of them only 0.4% required hospitalization [9, 10, 18, 19].

Management of pregnant trauma patient poses specific challenges that deserve establishing a safe and effective protocol for prompt and thorough assessment, monitoring and managing of the mother and fetus. The present study revealed that one quarter of the women of childbearing age who were presented to the HTC services were pregnant. The pregnant women were at increased risk of traumatic injuries during the 2nd or 3rd trimesters of pregnancy, and MVC was the most common mechanism of injury. One out of three MVCs among pregnant women occurred while they were driving their cars.

In our study, mortality included one maternal death (1.1%), 2 fetal deaths (2.1%) and 2 neonatal deaths (2.1%). The maternal death was reported in a 37-year-old lady during her 20th week of pregnancy. The patient was a passenger in a car and was seriously injured due to a crash which resulted in polytrauma (with mean ISS of 34). The patient was admitted to intensive care and connected to mechanical ventilator for 5 days before death. Placental abruption and fetal death were reported in this case. The second fetal death occurred in a 27-year-old woman who was involved in MVC during her 28th week of pregnancy while driving her car. The fetal death occurred at gestational age of 33 weeks.

In our study, the proportion of placental abruption was 4.2% which is less than the reported rates of 5–50% [20]. The major obstetrical concern with MVC is the strain positioned on the uterus leading to placental abruption. The estimated post-traumatic fetal mortality is around 3–7 deaths per 100,000 live births [18].

A national population-based study conducted in Sweden during 1991–2001 revealed that MVCs during pregnancy caused 1.4 maternal fatalities per 100,000 pregnancies [13]. The fetal and neonatal mortality rate was 3.7 per 100,000 pregnancies. The incidence of maternal major injury was 23/100,000 pregnancies and crash involvement was 207/100,000 pregnancies. Another population-based study in Australia reported that 3.5 women per 1000 maternities were admitted to hospital following MVCs [14].

The main risk factor for adverse outcomes during MVC is inappropriate seat belt use regardless of front or rear collisions. One population-based study in Turkey reported that only less than half of the prenatal visits received prenatal care provider counseling for seat belt use [20]. The use of intoxicants was also a major risk factor for MVC during pregnancy in some studies [21], however, this was not reported in our database.

The mean gestational age at the time of injury was approximately 25 weeks in our study. MVC-related trauma occurred in 39–48% in the second or third trimester of pregnancy. Evidence suggests that the majority of MVC-related trauma admissions occurs after 20 weeks of gestation [13]. The Australian study demonstrated that 0.4% of trauma occurred at a gestational age < 20 weeks and 3.5% at ≥ 20 weeks (7 times more) [13]. While the mean gestational age at MVC in our study was 25 weeks, the mean gestational age at delivery was 35 weeks, i.e., delivery immediately after MVC was uncommon in our study. Delivery immediately after trauma increases the risk of fetal deaths [13]. This could be one reason for low fetal mortality rate in our study along with other reasons such as low prevalence of complications such as placental abruption and fetal distress.

Fall-related trauma, another MOI, was reported in 16% of pregnant women in our study. Increased joint laxity and gain of body weight affect the gait and predispose pregnant women to slips and falls [22]. Almost 1 in 4 pregnant women is at risk of fall at least once while pregnant [23]. Young women of age 20–24 years are at twofold increased risk of fall than those over 35 years old [23].

Evidence suggests that ISS, blood loss, placental abruption and the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation were the significant predictors of fetal mortality [24].

Gilt-edge care of the mother improves fetal outcome, so management of pregnant women with trauma should focus primarily on the mother. Maternal evaluation should trail around with the guidelines to plan in detail by the Early Management of Severe Trauma (EMST)/Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) procedure to trauma, with a comprehensive primary and secondary assessment. Trauma in pregnancy should be an indication for transfer to trauma centers and activation of complete Trauma Team response to streamline the assessment and care [25].

Although, evidence suggests that pregnancy is not an independent predictor for the need for major trauma activation; still it remains as important criteria in the American College of Surgeons (ACS) guidelines, and all pregnant women involved in trauma need thorough assessment of the pregnancy status with adequate monitoring to rule out maternal and fetal injury [18]. Therefore, it is imperative that all professionals specializing in treating trauma patients recognize pregnancy as early as possible and its anatomic and physiologic changes that could influence their evaluation and treatment.

A woman of reproductive age with major injuries should be considered pregnant until proven otherwise by a definitive pregnancy test or ultrasound scan [16]. An obstetrician should have a consultative role in non-obstetric surgical care, obtain formal obstetric ultrasound, counseling and should intervene if trauma care is compromised by the pregnancy, i.e., severe trauma commonly calls for termination decision. In the resuscitation, perimortem cesarean delivery should be considered when fetal viability is a concern (≥ 23 weeks) iin a victim who sustained traumatic cardiac arrest within 4 min, whenever feasible [16].

After stabilization in the emergency setting, the patient should be shifted for appropriate maternal and specific fetal observation. Comprehensive and accurate documentation is necessary with recording of the chronology of events including maternal and fetal assessment, management and outcome. In general, pregnancy should not be an excuse for underdiagnosis or undertreatment post-trauma or unnecessary delay in obtaining the needful radiology and care related decisions [15]. Figure 5 shows an algorithm for management of pregnant woman presenting with traumatic injury in our institution.

Limitations

The sample size is not adequate to show the true statistical relationship between variables; however, there is an interest in more specific data collection in the coming years. Starting from August 2015; the trauma registry included the field of pregnancy (If the patient gender is female, then this conditional field has three questions that needs to be answered (1) Have you done a pregnancy test? if yes, then (2) Are you pregnant? if yes, then (3) What is the gestational age). Before that, data were collected from the emergency log book that may underestimate the actual number of patients with trauma during pregnancy.

The retrospective design of the study prevented obtaining important data such as blood loss, type of delivery, domestic violence, seatbelt status, and formal ultrasound results. In our center, we developed an evidence-based pathway for a quick and thorough multidisciplinary approach for all pregnant ladies who presented with trauma.

Conclusions

Incidence of trauma in pregnancy is not uncommon and requires a prompt and thorough multidisciplinary management approach. Early care should follow recommended principles and a formal ultrasound of the abdomen and protocolized fetal monitoring for signs of distress. Severe cases should be admitted in trauma ICU and followed regularly by obstetric team; more stable patients in delivery should be monitored in a labor ward under joint trauma and obstetric care. Detection of fetal distress should prompt immediate delivery often with cesarean. Further studies are needed for the most appropriate, cost-effectiveness management in pregnant trauma women.

References

Aniuliene R, Proseviciūte L, Aniulis P, Pamerneckas A. Trauma in pregnancy: complications, outcomes, and treatment. Medicina (Kaunas). 2006;42(7):586–91.

Hill CC, Pickinpaugh J. Trauma and surgical emergencies in the obstetric patient. Surg Clin N Am. 2008;88:421–40.

Petrone P, Jiménez-Morillas P, Axelrad A, Marini CP. Traumatic injuries to the pregnant patient: a critical literature review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0839-x.

Schiff MA, Holt VL, Daling JR. Maternal and infant outcomes after injury during pregnancy in Washington state from 1989 to 1997. J Trauma. 2002;53:939–45.

Pak LL, Reece EA, Chan L. Is adverse pregnancy outcome predictable after blunt abdominal trauma? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1140–4.

El-Kady D, Gilbert WM, Anderson J, Danielsen B, Towner D, Smith LH. Trauma during pregnancy: an analysis of maternal and fetal outcomes in a large population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1661–8.

Schiff MA, Holt VL. Pregnancy outcomes following hospitalization for motor vehicle crashes in Washington state from 1989 to 2001. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:503–10.

Oxford CM, Ludmir J. Trauma in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52(4):611–29.

Weiss HB, Songer TJ, Fabio A. Fetal deaths related to maternal injury. JAMA. 2001;286:1863–68.

Shah KH, Simons RK, Holbrook T, Fortlage D, Winchell RJ, Hoyt DB. Trauma in pregnancy: maternal and fetal outcomes. J Trauma. 1998;45(1):83–6.

Kuo C, Jamieson DJ, McPheeters ML, Meikle SF, Posner SF. Injury hospitalizations of pregnant women in the United States, 2002. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:161-e1.

Motozawa Y, Hitosugi M, Abe T, Tokudome S. Effects of seat belts worn by pregnant drivers during low-impact collisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:62-e1.

Kvarnstrand L, Milsom I, Lekander T, Druid H, Jacobsson B. Maternal fatalities, fetal and neonatal deaths related to motor vehicle crashes during pregnancy: a national population-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:946–52.

Vivian-Taylor J, Roberts CL, Chen JS, Ford JB. Motor vehicle accidents during pregnancy: a population-based study. BJOG. 2012;119:499–503.

Mendez-Figueroa H, Dahlke JD, Vrees RA, Rouse DJ. Trauma in pregnancy: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(1):1–10.

Jain V, Chari R, Maslovitz S, Farine D, Bujold E, Gagnon R, Basso M, Bos H, Brown R, Cooper S, Gouin K, McLeod NL, Menticoglou S, Mundle W, Pylypjuk C, Roggensack A, Sanderson F, Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee. Guidelines for the management of a pregnant trauma patient. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(6):553–74.

Graham L. CDC releases guidelines on improving preconception health care. Am Fam Phys. 2006;74(11):1967–70.

Battaloglu E, Porter K. Management of pregnancy and obstetric complications in prehospital trauma care: faculty of prehospital care consensus guidelines. Emerg Med J. 2017;34(5):318–25.

Pearlman MD, Tintinalli JE, Lorenz RP. A prospective controlled study of outcome after trauma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162(6):1502–10.

Sirin H, Weiss HB, Sauber-Schatz EK, Dunning K. Seat belt use, counseling and motor-vehicle injury during pregnancy: results from a multi-state population-based survey. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(5):505–10.

Patteson SK, Snider CC, Meyer DS, Enderson BL, Armstrong JE, Whitaker GL, Carroll RC. The consequences of high-risk behaviors: trauma during pregnancy. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):1015–20.

McCrory JL, Chambers AJ, Daftary A, Redfern MS. Dynamic postural stability during advancing pregnancy. J Biomech. 2010;43(12):2434–9.

Dunning K, Lemasters G, Bhattacharya A. A major public health issue: the high incidence of falls during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(5):720–5.

Ali J, Yeo A, Gana TJ, McLellan BA. Predictors of fetal mortality in pregnant trauma patients. J Trauma. 1997;42(5):782–5.

Lu WH, Kolkman K, Seger M, Sugrue M. An evaluation of trauma team response in a major trauma hospital in 100 patients with predominantly minor injuries. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:329–32.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the entire registry database team in the Trauma Surgery Section, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HA was involved in study design, data acquisition, writing the manuscript and review, AE&BS: study design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and critical review of manuscript; AM, MA, MM, ST, HA data acquisition, interpretation and drafting the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendment. This study obtained ethical approval from Research Ethics Committee, at Medical Research Center, Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar (IRB#15316/15).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest, no financial issues to disclose and no funding was received for this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Thani, H., El-Menyar, A., Sathian, B. et al. Blunt traumatic injury during pregnancy: a descriptive analysis from a level 1 trauma center. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 45, 393–401 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-0948-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-0948-1